1.4. Interactionist View

Shanell Sanchez

Tattoos at Work

An article by Forbes in 2015, encourages employers to revisit their dress code expectations, with a specific suggestion on lifting the ‘tattoo taboo.’ The article argues “allowing employees to maintain their style or grooming allows your company to project how genuine you are as a brand to employees and to the customers they support.” So, instead of suggesting tattoos are taboo in the workforce to employees, according to the article, one can encourage people to ‘project who they are’ by accepting tattoos and ultimately, improve your business. This example demonstrates how societal changes in deviance can change through time and space.

Read the Forbes article to learn more about this discussion:

Typically, in our society, a deviant act becomes a criminal act that can be prohibited and punished under criminal law when a crime is deemed socially harmful or dangerous to society.[1]

In criminology, we often cover a wide array of harms that can include economic, physical, emotional, social, and environmental. The critical thing to note is that we do not want to create laws against everything in society, so we must draw a line between what we consider deviant and unusual versus dangerous and criminal. For example, some people do not support tattoos and would argue they are deviant, but it would be challenging to suggest they are dangerous to individuals and society. However, thirty years ago, it may have been acceptable to put into dress code, rules guiding our physical conduct in the workspace, that people may not have visible tattoos and people may not be as vocal as they would today. Today, tattoos may be seen as more normalized and acceptable, which could lead to a lot of upset employees saying those are unfair rules in their work employment if they are against the dress code.

Now that we have a basis for understanding the differences between deviance, rule violations, and criminal law violations, we can discuss who determines if a law becomes criminalized or decriminalized in the United States. A criminalized act is when a deviant act becomes criminal and a law is written, with defined sanctions, that can be enforced by the criminal justice system. [2]

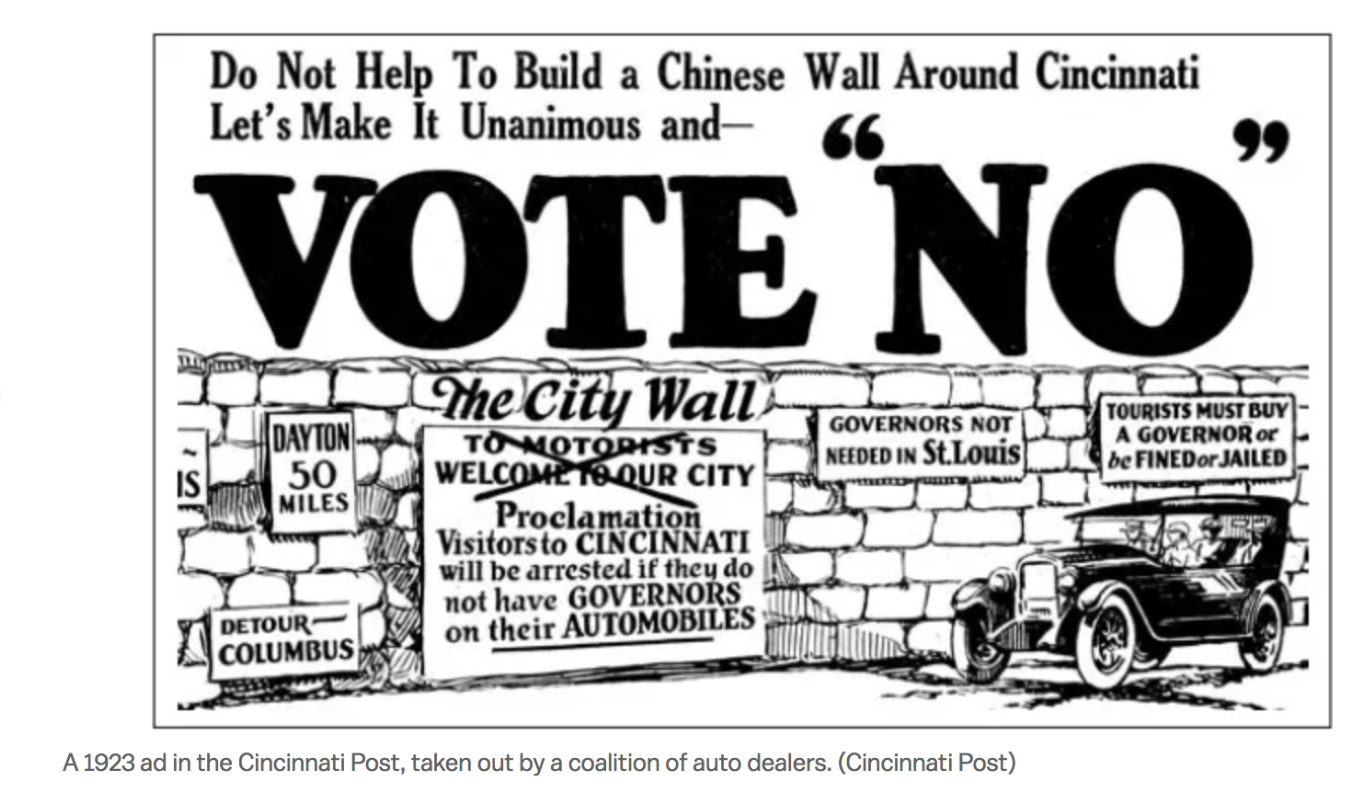

Jaywalking

In the 1920s, auto groups aggressively fought to redefine who owned the city street. As cars began to spread to the streets of America, the number of pedestrians killed by cars skyrocketed. At this time, the public was outraged that the elderly and children were dying in what was viewed as ‘pleasure cars’ because, at this time, our society was structured very differently and did not rely on vehicles. Judges often ruled that the car was to blame in most pedestrian deaths and drivers were charged with manslaughter, regardless of the circumstances. In 1923, 42,000 Cincinnati residents signed a petition for a ballot initiative that would require all cars to have a governor limiting them to 25 miles per hour, which upset auto dealers and sprang them into action to send letters out to vote against the measure.

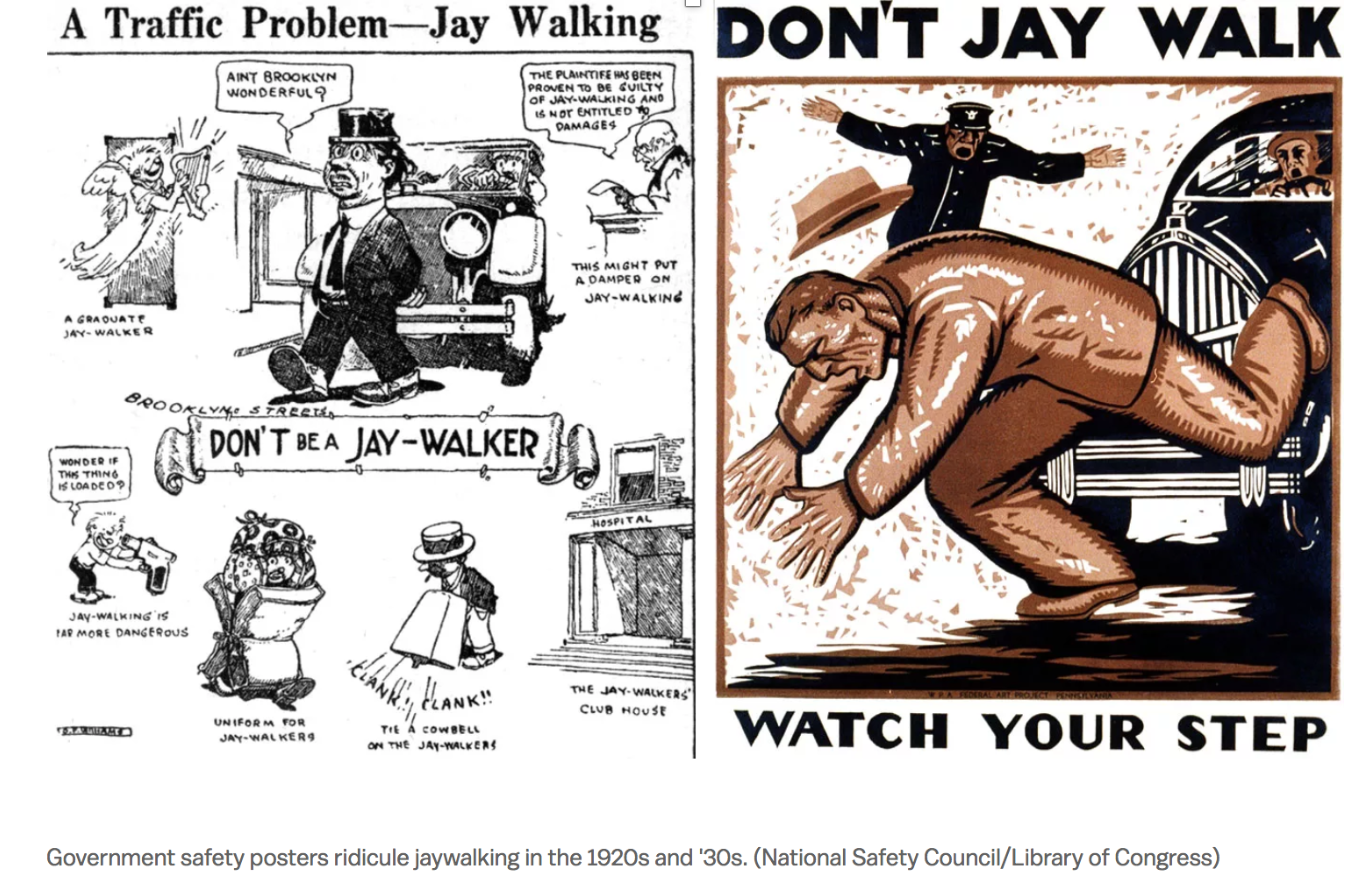

It was at this point that automakers, dealers, and others worked to redefine the street so that pedestrians, not cars, would be restricted. Today, these law changes can be seen in our expectations for pedestrians to only cross at crosswalks.

The Vox Article below has an excellent summary of what we discussed:

The creation of jaywalking laws would be an example of the interactionist view in lawmaking. The interactionist view states that the definition of crime reflects the preferences and opinions of people who hold social power in a particular legal jurisdiction, such as the auto industry. The auto industry used its power and influence to impose what it felt was right and wrong and became moral entrepreneurs. [3]

A moral entrepreneur was a phrase coined by sociologist Howard Becker. Becker referred to individuals who use the strength of their positions to encourage others to follow their moral stances. Moral entrepreneurs create rules and argue their causes will better society, and they have a vested interest in that cause that maintains their political power or position. [4] [5]

The auto industry used aggressive tactics to garner support for the new laws: using news media to shift the blame for accidents of the drivers and onto pedestrians, campaigning at local schools to teach about the importance of staying out of the street, and shame by suggesting you are in the wrong if you get hit. [6]

- Goode, E. (2016). Deviant Behavior. Routledge: New York. ↵

- Farmer, L. (2016). Making the modern criminal law: Criminalization and civil order. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Vuolo, M., Kadowaki, J., & Kelly, B. (2017). Marijuana's Moral Entrepreneurs, Then and Now. https://contexts.org/articles/marijuanas-moral-entrepreneurs/ ↵

- Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: Free Press. ↵

- Cole, J.M. (2013). Guidance regarding marijuana enforcement. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Office of the Deputy Attorney General. Better known as the "Cole Memorandum," ↵

- Norton, P. (2007). Street rivals: Jaywalking and the invention of the Motor Age street. Fighting traffic: The dawn of the motor age in the American city ↵