6.2 Brief History of Policing

In this section, we will review the progression and establishment of policing through the beginning years of United States history. We will discuss the influences on policing from England as well as the impacts of Sir Robert Peel and Chief August Vollmer. We will also review the disturbing histories of how some have been discriminated against and even targeted by police based on their race. As these historical events and influences are discussed, reflect on how they have impacted certain groups and communities more negatively than others.

As you will see in this section, the terms “police officer” and “law enforcement officer” are used interchangeably without any gender reference, but what should be noted is the phrasing difference between “policeman/men” and “police officer.” This differentiation was done intentionally by the authors, as through many of the policing eras, women, in general, were not allowed to work in the profession. If they were hired, it was under a microscopic view of certain stereotypical “matronly” duties. Some of these will be discussed in further detail within the section. The other noteworthy point is the reference to “policeman/men” being predominantly White as men of color, and more specifically, Black men were rarely hired. A few Black policemen made their way into policing in the late 1800s in the northern states. Still, when the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was ruled unconstitutional, most Black police officers disappeared from policing until the 1950s. This will be explained further within the section.

6.2.1 Policing in Ancient Times

The development of policing in the United States coincided with the development of policing in England. The United States’ legal system traces its roots back to the common law of England. However, looking back before 1750 B.C. to see how forms of policing were common during ancient times, to what is now known as kin policing. Kin policing is when a tribe or clan policed their own tribe, and it often turned bloody quickly. The blood feuds would go on for long periods of time (Berg, 1999).

However, it is estimated, also sometime around 1750 B.C., that the Code of Hammurabi was engraved in stone. This code detailed 282 sections of how one individual should treat another individual in society and the penalties for such violations. The code is seen as the beginnings of law and justice. Around 1000 B.C., Mosaic Law emerged. This was a new form of rational law that hoped to predict prohibited behaviors. In Mosaic Law, the ruling class did not create the law. The Code of Hammurabi and Mosaic Law formed the ladder that would eventually lead to the creation of policing as we now know it today (Berg, 1999).

Peisistratus (605-527 B.C.), the ruler of Athens, has been called the father of formal policing. During this time of growth, new Greek city-states were being developed, and blood feuds that lasted decades had to be quashed. Kin policing slowly faded due to its barbaric nature, and new doors opened for a modern city-driven policing model. The first police service in Athens was developed by Sparta, and it is often looked at as the first secret service (Berg, 1999).

Augustus Caesar (27 BC), the first emperor of Rome, was instrumental in creating what is now called the urban cohorts. The urban cohorts were men from the Praetorian Guard (Augustus’ army), charged with ensuring peace in the city. As crime rose and became more violent, Augustus formed the vigils, which were not affiliated with the Praetorian Guard, but were charged with fighting crime and fires. The vigils were given the power to protect and arrest (Berg, 1999).

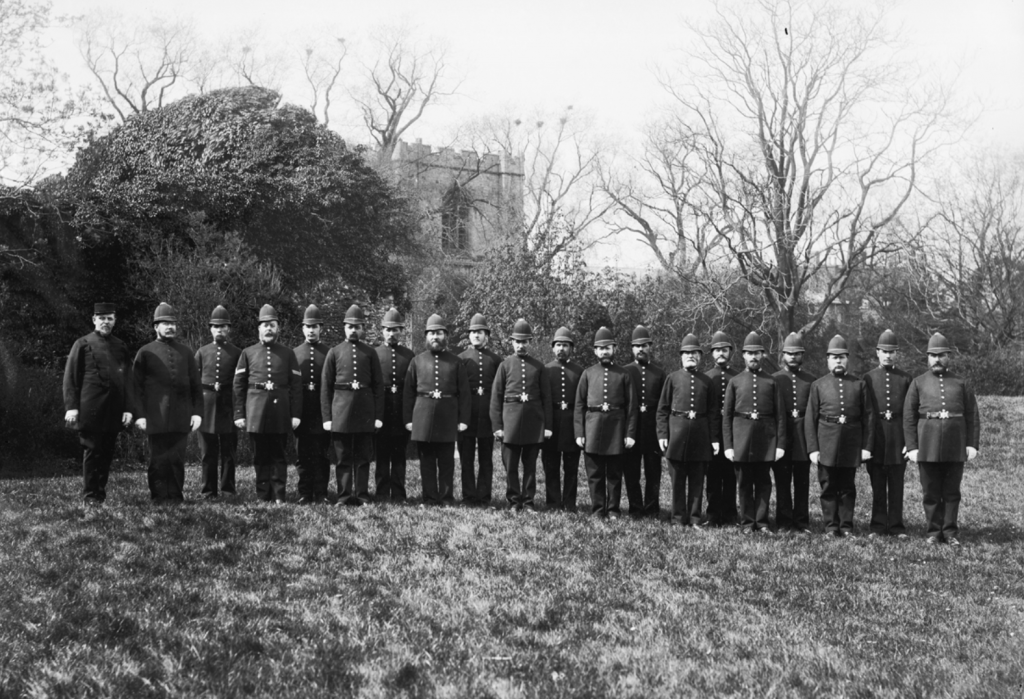

From 6 A.D. until the 12th century, Rome was patrolled day and night by a public police force. With the fall of the Roman Empire, kings then assumed the role of protection. From the 12th-18th centuries, kings in England appointed sheriffs. At age fifteen, boys could volunteer with the posse comitatus to go after wanted felons. Constables, a policeman with limited authority, assisted the sheriffs with serving summons and warrants. Because young volunteers did the policing work, there were several problems, such as corruption and drunkenness. Victims who had the means to hire private police or bodyguards did so for protection, but unfortunately, that meant those who were poor and disadvantaged had neither help nor protection (Berg, 1999) and thus were more of a target. In figure 6.1., you can see an image of a group of police from Suffolk, England.

Figure 6.1. A photograph of Police in England.

6.2.2 Sir Robert Peel

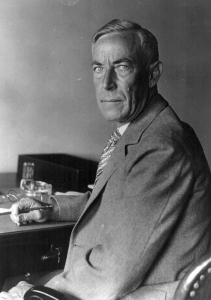

The 19th century in England heavily influenced the history of policing in the United States. Not only did policing radically change for the first time in over six centuries, but the father of modern policing, Sir Robert Peel, seen in figure 6.2, set the stage for what is known today as modern policing. Sir Robert Peel, the British Home Secretary, coined the term “bobbies” as a nickname for policemen, and he believed policing needed to be restructured. In 1829 he passed the Metropolitan Police Act, which created the first British police force and what the 21st century now knows as modern-day police (Cordner et al., 2017).

Figure 6.2. Image of Sir Robert Peel.

Sir Robert Peel is best known for the Peelian Principles. He did not create the twelve principles but used a combination of previous codes that he expected police to follow. The exact historical origins of the twelve listed principles below are unknown. Still, it has been theorized that the principles were slowly created over the years by academics studying Peel (Cordner et al., 2017):

6.2.2.1 Peelian Principles

- The police must be stable, efficient, and organized along military lines;

- The police must be under government control;

- The absence of crime will best prove the efficiency of police;

- The distribution of crime news is essential;

- The deployment of police strength both by time and area is essential;

- No quality is more indispensable to a policeman than perfect command of temper; a quiet, determined manner has more effect than violent action;

- Good appearance commands respect;

- The securing and training of proper persons is at the root of efficiency;

- Public security demands that every police officer be given a number;

- Police headquarters should be centrally located and easily accessible to the people;

- Policemen should be hired on a probationary basis; and

- Police records are necessary to the correct distribution of police strength.

6.2.3 Policing Eras

With the influence brought to the United States by England, much of the early history was influenced by what the immigrants had previously experienced in their mother countries. These ways of policing were passed down from generation to generation until political figures and policymakers established in the United States started to make changes, influencing the progression of police changes in the coming years or eras. Researchers Kelling and Moore (1991) evaluated the first three eras of policing in the United States. These eras are discussed in this section and are often referred to as the Political Era, the Reform Era, and the Community Era. These eras impacted the way the police forces were organized and what their focuses were during a specific time period, in general terms.

6.2.3.1 The Political Era

The political era is often referred to as the first era of policing in the United States. It began around the 1840s with the creation of the first bonafide police agencies in America. (Kelling et al, 1991).

This era of policing was marked by the industrial revolution, the abolishment of slavery, and the formation of large cities. With the advent of the industrial revolution came goods and services. Along with new job opportunities came a myriad of conflicts as well. With the abolishment of slavery, the Klu Klux Klan began to make terrifying appearances, and their reign of terror left many in fear. Policing had not yet formally entered the scene; therefore, the Klan operated virtually unencumbered. The fast-growing cities answered these problems in the form of policing.

6.2.3.2 Some of the City Police Agencies Established During the Political Era

The United States saw tremendous growth in major cities resulting in the creation of police departments across the United States in larger cities as noted:

- New York Police Founded 1845

- Chicago Police Founded 1855

- Philadelphia Police Founded 1751

- Jacksonville Police Founded 1822

- Detroit Police Founded 1865

- Portland Police Founded 1870

With each of these three influences, the Political Era of policing was set into motion. As its name suggests, it was an era of politics, mainly because of how policing was limited due to new laws made clear by the Constitution. America answered the call by following the English and Sir Robert Peel’s principles. Not unlike today, policing during this era was under the control of politicians. Politicians, like the mayor, had no problem controlling everything a policeman did during his call of duty.

6.2.3.3 Reform Era

Because the Political Era of policing ended up being laced with corruption and brutality, the panacea for the negativity became the Reform Era. One police chief was largely at the forefront of this new era, Chief August Vollmer. He is considered the pioneer for police professionalism. August Vollmer was the Chief of Police in Berkeley, California (1905–1932). He had many new beliefs about policing that would forever change the world of policing to include:

- Candidates who were testing to be in policing had to undergo psychological and intelligence tests.

- Detectives would utilize scientific methods in their investigations, through forensic laboratories.

- Recruits, for the first time, would attend a training academy (police did not receive any formal training prior to August Vollmer’s arrival).

- Assisted with the development of the School of Criminology at the University of California at Berkeley.

Chief August Vollmer saw policing and officers as social workers that needed to delve into the causes behind the acts in order to solve the issue, instead of just arresting it (Reppetto, 1978). He knew to rehabilitate offenders, police officers needed to look beyond the handcuffs and start looking into the person and the reason behind the behavior (Reppetto, 1978).

Figure 6.3. An image of Chief August Vollmer the Father of modern law enforcement.

Diversity in policing started to make a mark during this era, but it would fall irrevocably far from meeting any type of standard. It was a better era for diversity in that agencies started to hire some women and those of varying races than the Political Era, but nowhere near what the population ratios were at the time.

6.2.3.4 The Community Era- 1980s to 2000

In the 1960s and 1970s, the crime rate doubled, and it was a time of unrest and eye-opening policing issues. Civil rights movements spread across America, and the police were on the front lines. Media coverage showed controversial contact between White male officers and Black community members, which further irritated race relations in policing. The U.S. Supreme Court handed down the landmark Miranda v. Arizona and Mapp v. Ohio decisions. The writing was on the wall that the policing environment had to change. The days of answering everything with bullying or police professionalism were no more. The Community Era of policing began, and those in police administration hoped this new era held the answers to fixing decades-old issues. The police needed help, and they would turn to the community and its members for assistance.

This new era of community policing held that police could not act alone; the community must pitch in as well. Whether the problems were a dispute between neighbors or high crime area drugs and shootings, these issues did not develop overnight and could not be solved by a response of police alone. Instead, these community problems needed a pronged approach where the police worked together with the community, and over time the issues could be systematically solved. Out-of-the-box thinking was common in community policing, and often community leaders were identified in order to make an impact. During this time, police candidates started showing up to the application process with Associates and Bachelors degrees. The “old school officers” mocked these degree-holding candidates, but the landscape was changing, and officers needed more thorough training than ever to answer the call.

Problem-oriented policing was an after-effect of community policing in that it utilized community policing but focused on the problems first. The biggest difference was problem-oriented policing used a defined process for working toward the solution. The problem was torn apart layer by layer and rebuilt according to set parameters that had a proven record of working.

The Community Era was also a time for research. Prior to this era, research on crime, police, or criminal justice topics were few and far between. With new federal government funding options available, this era’s missions could be accomplished through grants and the needed research began. Proof of what worked, what did not, and suggestions on how to improve policing were abundant. Without research or studies, policing can become stagnant, but with funding available, the answers were a questionnaire or interview away, and solutions came rolling in.

6.2.3.5 The Homeland Security Era- 2001 to Present

On September 11, 2001, when terrorists hijacked airplanes and flew them into the World Trade Center buildings and Pentagon in the United States, a fourth era of policing, the era of Homeland Security, was said to emerge (Oliver, 2006). The long-lasting repercussions of this terrorist act would forever change life for Americans.

The realities of the tragedy of 9/11 were that it did start a new era of policing. In fact, a case could be made for the large dark line that became metaphorically visible on September 11, 2001, when the Community Era shifted to the Homeland Security Era as airplanes destroyed America’s feelings of safety. Although the focus shifted to Homeland Security, policing has continued to involve some Community Era policing components.

Figure 6.4. An image of destruction on the streets of New York following the 9/11 Tragedy.

Policing under Homeland Security was marked by a more focused concentration of its resources on crime control, enforcement of criminal law, traffic law, etc., to expose potential threats and gather intelligence (Oliver, 2006).

Scholars have examined the pros and cons of a national police department in the United States. For example, Canada has a Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Depending on location, one could go through several different cities and counties while driving to the store, all of which have their own respective police departments. With the advent of the Homeland Security Era, a new model of centralized organizational control began due to the need for information dissemination. One of the biggest flaws of 9/11 was the lack of communication between law enforcement agencies. The Department of Homeland Security was developed, and one of its first major missions became the dissemination of information and communication. While a national police department does not exist in the United States, communication and information are now a common thread that binds all of the different types of law enforcement agencies.

6.2.4 Racialized and Biased History

As mentioned previously in the policing eras of the United States, law enforcement and minority groups have a rocky past, but this past started even before the policing eras began. The NAACP’s website titled, The Origins of Modern Day Policing, explains that in the early 1700s, “Slave Patrols” were established in which white men were used to “establish a system of terror and squash slave uprisings with the capacity to pursue, apprehend and return runaway slaves to their owners. Tactics included the use of excessive force to control and produce desired slave behavior.” (2021). The article goes on to explain that,

“Slave Patrols continued until the end of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment. Following the Civil War, during Reconstruction, slave patrols were replaced by militia-style groups who were empowered to control and deny access to equal rights to freed slaves. They relentlessly and systematically enforced Black Codes, strict local and state laws that regulated and restricted access to labor, wages, voting rights, and general freedoms for formerly enslaved people.” (NAACP, 2021)

The Black Codes continued to be enforced up until 1868, when the 14th Amendment of the Constitution was ratified, thus abolishing these codes, but in response individual states and local governments began passing Jim Crow laws, legalizing segregation in public places. With the creation of police departments, as noted in the political era, it became the role of policemen to thus enforce the Jim Crow Laws, which were in place until the 1960s (NAACP, 2021). To learn more about Jim Crow Laws, review Social Welfare History Project Jim Crow Laws and Racial Segregation.

Before the 1960s, as long as an individual was a white male, police officer positions were his for the taking. Women and minorities were all but non-existent on the force. Women were allowed into the “boys only club” if they wore a pencil skirt and fit a prescribed role consistent with being a woman. In some departments, women were allowed to work in the detective bureau and interview children victims because women supposedly talked to children better than men because of their “maternal” instincts. These stereotypes continued in policing towards women and minorities until new laws, forbidding such behavior, made their way into the scene. With new employment laws passed between the 1960s to the late 1990s, many doors opened for women and minorities who were interested in becoming police officers.

6.2.5 Licenses and Attributions for Brief History of Policing

“Brief History of Policing” by Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “6.1. Policing in Ancient Times”, “6.2. Sir Robert Peel”, and “6.3. Policing Eras” by Tiffany Morey in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 6.1. Police Group Portrait Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, England is in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.2. Sir Robert Peel is in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.3. August Vollmer, “father of modern law enforcement” is in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.4. LOC unattributed Ground Zero Photos, September 11, 2021-item 111 is in the Public Domain.