2.6 Re-Evaluating Policy

Throughout American history, groups have come together to draw attention to some of the inequities within criminal justice policy, sometimes leading to a re-evaluation of the policy and thus new processes put in place. Some of these re-evaluations have been a result of public outcry to media attention and others have been in relation to statistical data showing results that were less than desirable in regards to the intent of the original policy. We will look at a few examples in this section and others will be considered in future chapters.

2.6.1 Black Lives Matter

One organization that has focused its efforts on re-evaluating criminal justice policy is The Sentencing Project. The organization has been at the forefront of collecting and disbursing information related to reform efforts and options. In their article, “Black Lives Matter: Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice System,” they outline some “best practices for reducing racial disparities” through criminal justice policy reform and note “Jurisdictions around the country have implemented reforms to address these sources of inequality. This section showcases best practices from the adult and juvenile justice systems. In many cases, these reforms have produced demonstrable results” (Ghandoosh, 2015).

2.6.1.1 Research from The Sentencing Project On Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice System

2.6.1.2 The Sentencing Project – Black Lives Matter:Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice System by Nazgol Ghandoosh (Pages 19-20 Excerpt)

1) REVISE POLICIES AND LAWS WITH DISPARATE RACIAL IMPACT

Through careful data collection and analysis of racial disparities at various points throughout the criminal justice system, police departments, prosecutor’s offices, courts, and lawmakers have been able to identify and address sources of racial bias.

Revise policies with disparate racial impact: Seattle; New York City; Florida’s Miami-Dade and Broward County Public Schools; Los Angeles Unified School District.

- After criticism and lawsuits about racial disparities in its drug law enforcement, some precincts in and around Seattle have implemented a pre-booking diversion strategy: the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion program (Knafo, 2014). The program gives police officers the option of transferring individuals arrested on drug and prostitution charges to social services rather than sending them deeper into the criminal justice system.

- Successful litigation and the election of a mayor with a reform agenda effectively curbed “stop and frisk” policing in New York City (Bostock & Fessenden, 2014). Mayor Bill de Blasio vowed that his administration would “not break the law to enforce the law” and significantly curbed a policy that was described by a federal judge as one of “indirect racial profiling (2014). Thus far, the reform has not had an adverse impact on crime rates (Bostock & Fessenden, 2014). In a related effort to address disparities in enforcement, the New York City Police Department stated it would no longer make arrests for possession of small amounts of marijuana but would instead treat these cases as non-criminal offenses subject to a fine rather than jail time (Goldstein, 2014). Yet experts worry that this policy does not go far enough to remedy unfair policing practices and may still impose problematic consequences on those who are ticketed (Sayegh, 2014).

- Several school districts have enacted new school disciplinary policies to reduce racial disparities in out-of-school suspensions and police referrals. Reforms at Florida’s Miami-Dade and Broward County Public Schools have cut school-based arrests by more than half in five years and significantly reduced suspensions (Smiley & Vacquez, 2013). In Los Angeles, the school district has nearly eliminated police-issued truancy tickets in the past four years and has enacted new disciplinary policies to reduce reliance on its school police department (Watanade, 2013). School officials will now deal directly with students who deface property, fight, or get caught with tobacco on school grounds. Several other school districts around the country have begun to implement similar reforms.

Revise laws with disparate racial impact: Federal; Indiana; Illinois; Washington, D.C.

- The Fair Sentencing Act (FSA) of 2010 reduced from 100:1 to 18:1 the weight disparity in the amount of powder cocaine versus crack cocaine that triggers federal mandatory minimum sentences. If passed, the Smarter Sentencing Act would apply these reforms retroactively to people sentenced under the old law. California recently eliminated the crack-cocaine sentencing disparity for certain offenses, and Missouri reduced its disparity. Thirteen states still impose different sentences for crack and cocaine offenses (Porter & Wright, 2011).

- Indiana amended its drug-free school zone sentencing laws after the state’s Supreme Court began reducing harsh sentences imposed under the law and a university study revealed its negative impact and limited effectiveness. The reform’s components included reducing drug-free zones from 1,000 feet to 500 feet, eliminating them around public housing complexes and youth program centers, and adding a requirement that minors must be reasonably expected to be present when the underlying drug offense occurs. Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and South Carolina have also amended their laws (Porter & Clemons, 2013).

- Through persistent efforts, advocates in Illinois secured the repeal of a 20-year-old law that required the automatic transfer to adult court of 15- and 16-year-olds accused of certain drug offenses within 1,000 feet of a school or public housing. A broad coalition behind the reform emphasized that the law was unnecessary and racially biased, causing youth of color to comprise 99% of those automatically transferred.

- Following a campaign that emphasized disparate racial enforcement of the law, a ballot initiative in Washington, D.C. may legalize possession of small amounts of marijuana in the district (Sebens, 2014).

Address upstream disparities: New York City; Clayton County, GA.

- The District Attorney of Brooklyn, New York informed the New York Police Department that he would stop prosecuting minor marijuana arrests so that “individuals, and especially young people of color, do not become unfairly burdened and stigmatized by involvement in the criminal justice system for engaging in non-violent conduct that poses no threat of harm to persons or property” (Clifford & Goldstein, 2014).

- Following a two-year study conducted in partnership with the Vera Institute of Justice, Manhattan’s District Attorney’s office learned that its plea guidelines emphasizing prior arrests created racial disparities in plea offers. The office will conduct implicit bias training for its assistant prosecutors, and is being urged to revise its policy of tying plea offers to arrest histories (Kutateladze, 2014).

- Officials in Clayton County, Georgia reduced school-based juvenile court referrals by creating a system of graduated sanctions to standardize consequences for youth who committed low level misdemeanor offenses, who comprised the majority of school referrals. The reforms resulted in a 46% reduction in school-based referrals of African American youth.

Anticipate disparate impact of new policies: Iowa; Connecticut; Oregon; Minnesota.

- Iowa, Connecticut, and Oregon have passed legislation requiring a racial impact analysis before codifying a new crime or modifying the criminal penalty for an existing crime. Minnesota’s sentencing commission electively conducts this analysis. This proactive approach of anticipating disparate racial impact could be extended to local laws and incorporated into police policies.

Revise risk assessment instruments: Multnomah County, OR; Minnesota’s Fourth Judicial District.

- Jurisdictions have been able to reduce racial disparities in confinement by documenting racial bias inherent in certain risk assessment instruments (RAI) used for criminal justice decision making. The development of a new RAI in Multnomah County, Oregon led to a greater than 50% reduction in the number of youth detained and a near complete elimination of racial disparity in the proportion of delinquency referrals resulting in detention. Officials examined each element of the RAI through the lens of race and eliminated known sources of bias, such as references to “gang affiliation” since youth of color were disproportionately characterized as gang affiliates often simply due to where they lived.

- Similarly, a review of the RAI used in consideration of pretrial release in Minnesota’s Fourth Judicial District helped reduce sources of racial bias. Three of the nine indicators in the instrument were found to be correlated with race, but were not significant predictors of pretrial offending or failure to appear in court. As a result, these factors were removed from the instrument.

Check out the entire article here at BLACK LIVES MATTER: Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Criminal Justice System.

2.6.2 LGBTQIA+

Profile: Anti-LGBTQIA+ Hate Crimes In The United States: Histories and Debates by Ariella Rotramel.

On June 12, 2016, forty-nine people were killed and fifty-three wounded in the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. It was the deadliest single-person mass shooting and the largest documented anti-LGBTQIA+ attack in U.S. history. Attacking a gay nightclub on Latin night resulted in over 90 percent of the victims being Latinx and the majority being LGBTQIA+ identified. This act focused on an iconic public space (figure 2.5) that provided LGBTQIA+ adults an opportunity to explore and claim their sexual and gender identities. The violence at Pulse echoed the 1973 UpStairs Lounge arson attack in New Orleans that killed thirty-two people. These mass killings are part of a broader picture of violence that LGBTQIA+ people experience, from the disproportionate killings of transgender women of color to domestic violence and bullying in schools. There are different perspectives within the LGBTQIA+ community about responses to hate-motivated violence. These debates concern whether the use of punitive measures through the criminal legal system supports or harms the LGBTQIA+ community and whether more radical approaches are needed to address the root causes of anti-LGBTQIA+ violence. This profile explores hate crimes as both a legal category and a broader social phenomenon.

2.6.2.1 What Are Hate Crimes?

Anti-LGBTQIA+ hate crimes have had a simultaneously spectacular and invisible role in U.S. society. Today, hate crimes are defined as criminal acts motivated by bias toward victims’ real or perceived identity groups (Blazak, 2011). Hate crimes are informal social control mechanisms used in stratified societies as part of what Barbara Perry calls a “contemporary arsenal of oppression” for policing identity boundaries (Perry, 2009). Hate crimes occur within social dynamics of oppression, in which other groups are vulnerable to systemic violence, pushing marginalized groups further into the political and social edges of society. It is theorized that hate crimes are driven by conflicts over cultural, political, and economic resources; bias and hostility toward relatively powerless groups; and the failure of authorities to address hate in society (Turpin-Petrosin, 2009).

Figure 2.5. An image of flowers, candles and flags left at the Stonewall Inn memorial.

Figure 2.5. An image of flowers, candles and flags left at the Stonewall Inn memorial.

Prejudicial cultural norms perpetuate otherness, promoting prejudice and normalizing and rewarding hate, as well as punishing those who respect and embrace difference (Levin & Rabrenovic, 2003; Perry, 2003). Cultures of hate identify marginalized groups as enemies through dehumanization and perpetuate group violence (Levin & Rabrenovic, 2003; Perry, 2003). Perpetrators’ actions thus reflect an understanding and navigation of overarching social structures that separate the othered from the accepted.

In the case of anti-LGBTQIA+ hate crimes, heterosexism is an oppressive ideology that rejects, degrades, and others “any non-heterosexual form of behavior, identity, relationship or community.” It provides a complementary bias to cissexism, the oppressive ideology that denigrates transgender, gender nonbinary, genderqueer, and gender-nonconforming people (Herek, 1992). Anti-LGBTQIA+ hate crimes are based on a view of the LGBTQIA+ community as a suitable target for violence (Perry, 2005) (Green, et al, 2001). Such crimes are often identified as hate-based by such factors as that “the perpetrator [was] making homophobic comments; that the incident had occurred in or near a gay-identified venue; that the victim had a ‘hunch’ that the incident was homophobic; that the victim was holding hands with their same-sex partner in public, or other contextual clues”(Chakraborti & Garland, 2009). Importantly, anti-LGBTQIA+ hate crimes intersect with hate crimes against gender, racial and ethnic groups, and other marginalized people (Dunbar, 2006).

State-enacted or state-sanctioned violence against LGBTQIA+ people has not been deemed a form of hate crime, though it draws on hatred toward a group of people. The hate-crime framework has focused largely on the acts of private individuals rather than addressing larger institutionalized forms of hate-motivated violence such as forced conversion therapy or abuse within the criminal and military systems. One estimate attributes almost one-quarter of hate crimes to police officers (Berrill, 1990).

Anti-LGBTQIA+ violence committed by police officers undermines LGBTQIA+ victims’ willingness to report crimes, particularly after experiencing police violence firsthand or having communal knowledge that police officers may not view LGBTQIA+ victims as deserving of appropriate services. Even when victims are willing to take the risk of reporting a hate crime, they can be unsuccessful. For example, despite a Minnesota state law requiring police to note in initial reports any victims’ belief that they have experienced a bias-motivated incident, responding officers fulfilled less than half of hate-crime filing requests between 1996 and 2000 (Wolff & Cokely, 2007). Because of bias, lack of training, and limited application, significant underreporting of sexual orientation and gender-motivated hate crimes occurs at the state and federal levels.

2.6.2.2 Historical LGBTQIA Policy

The Enforcement Act of 1871, also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, addressed rampant anti-Black violence and marked the first effort at the federal level to criminalize hate crimes (Lurie & Chase, 2004). However, the Supreme Court’s United States v. Harris decision in 1883 greatly weakened the act and the ability of the federal government to intervene when states refused to prosecute hate crimes (1883). In the wake of the mid-twentieth-century civil rights movement and violence against activists, the 1968 Civil Rights Law covering federally protected activities was signed into law. It gave federal authorities the power to investigate and prosecute crimes motivated by actual or perceived race, color, religion, or national origin while a victim was engaged in a federally protected activity—for example, voting, accessing a public accommodation such as a hotel or restaurant, or attending school. The categories of identity named by the law were the key social categories of concern during this period and followed the language of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, the law excluded sex, reflecting an unwillingness to address gender-based discrimination fully rather than piecemeal through laws such as Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972.

In 1978, California enacted the first state law enhancing penalties for murders based on prejudice against the protected statuses of race, religion, color, and national origin. State lawmakers took the lead in developing explicit hate-crime laws, and federal legislators followed suit in the mid-1980s (Jennes & Grattet, 2001). The emergent LGBTQIA+ movement gained traction in the 1980s as the HIV/AIDS epidemic, its toll on the community, and intolerance toward its victims galvanized activists. For example, New York’s Anti-Violence Project (AVP) was founded in 1980 to respond to violent attacks against gay men in the Chelsea neighborhood. A major concern for these groups was the lack of documentation of such crimes; without evidence that these incidents were part of a broader picture of violence, it was difficult to push efforts to address hate crimes. As a lead member of the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, AVP has coordinated many hate-violence reports since the late 1990s (AVP, 201). Such groups also have pushed for governmental efforts to collect data and criminalize hate crimes.

In 1985, U.S. Representative John Conyers proposed the Hate Crime Statistics Act to ensure the federal collection and publishing annually of statistics on crimes motivated by racial, ethnic, or religious prejudice (Perry, 1985). It took five years for the Hate Crimes Statistics Act to become law, in 1990, and it did so only after sexual orientation was explicitly excluded from the legislation. The text of the law emphasizes that nothing in the act (1) “creates a cause of action or a right to bring an action, including an action based on discrimination due to sexual orientation” and (2) “shall be construed, nor shall any funds appropriated to carry out the purpose of the Act be used, to promote or encourage homosexuality” (1990).

Congress took great pains to emphasize that the legislation did not prevent discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people nor did it support that community. The law reinforces that Congress was not treating sexual orientation as it did other social identities that were already protected under civil rights laws. The law resulted in the Federal Bureau of Investigation collecting data from local and state authorities about hate crimes, but there are major challenges to collecting accurate data. Police are not consistently trained at the local and state levels to address anti-LGBTQIA+ hate crimes, and there continues to be stigma and risk associated with identifying as LGBTQIA+ to such authorities. Reporting practices thus vary dramatically across contexts, but the law has assisted anti-violence groups in gaining official data to document violence.

The 1998 beating and torture death of college student Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyoming, became a rallying point to address hate crimes more fully in the late 1990s. His murder received substantial media coverage and inspired political action as well as artistic works. As an affluent, white, gay young man, Shepard became a symbol of antigay violence. His attackers were accused of attacking him because of antigay bias but were not charged with committing a hate crime because Wyoming had no laws that covered anti-LGBTQIA+ crimes. The attention to his death contrasted with the lesser attention given to Brandon Teena’s sexual assault and murder, which was immortalized in the film Boys Don’t Cry (1999), and to the untold number of murders of trans women, particularly women of color (Wikipedia contributors, 2022).

Although the particularities of the case have been debated, Shepard’s murder became iconic and served as a means of challenging U.S. lawmakers and society at large to address hate-motivated violence. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on October 8, 2009, and the U.S. Senate on October 22, 2009 (Bessel, 2010). James Byrd Jr., a Black man, was attacked, chained to a truck, and dragged to his death for over two miles in Jasper, Texas. Both crimes received national attention, and there was public outrage that neither Texas nor Wyoming could enhance the punishment for these bias-motivated murders (McPhail, 2000).

The act expanded protections to victims of bias crimes that were “motivated by the actual or perceived gender, disability, sexual orientation, or gender identity of any person,” becoming the first federal criminal prosecution statute addressing sexual orientation and gender-identity-based hate crimes (DOJ, 2018). It also increased the punishment for hate-crime perpetrators and allowed the Department of Justice to assist in investigations and prosecutions of these crimes. On October 28, 2009, in advance of signing the act into law, President Barack Obama stated, “We must stand against crimes that are meant not only to break bones, but to break spirits, not only to inflict harm, but to inflict fear.” His words emphasized the broader social context of hate crimes, experienced as attacks on marginalized communities (Office of the Press Secretary, White House, 2009).

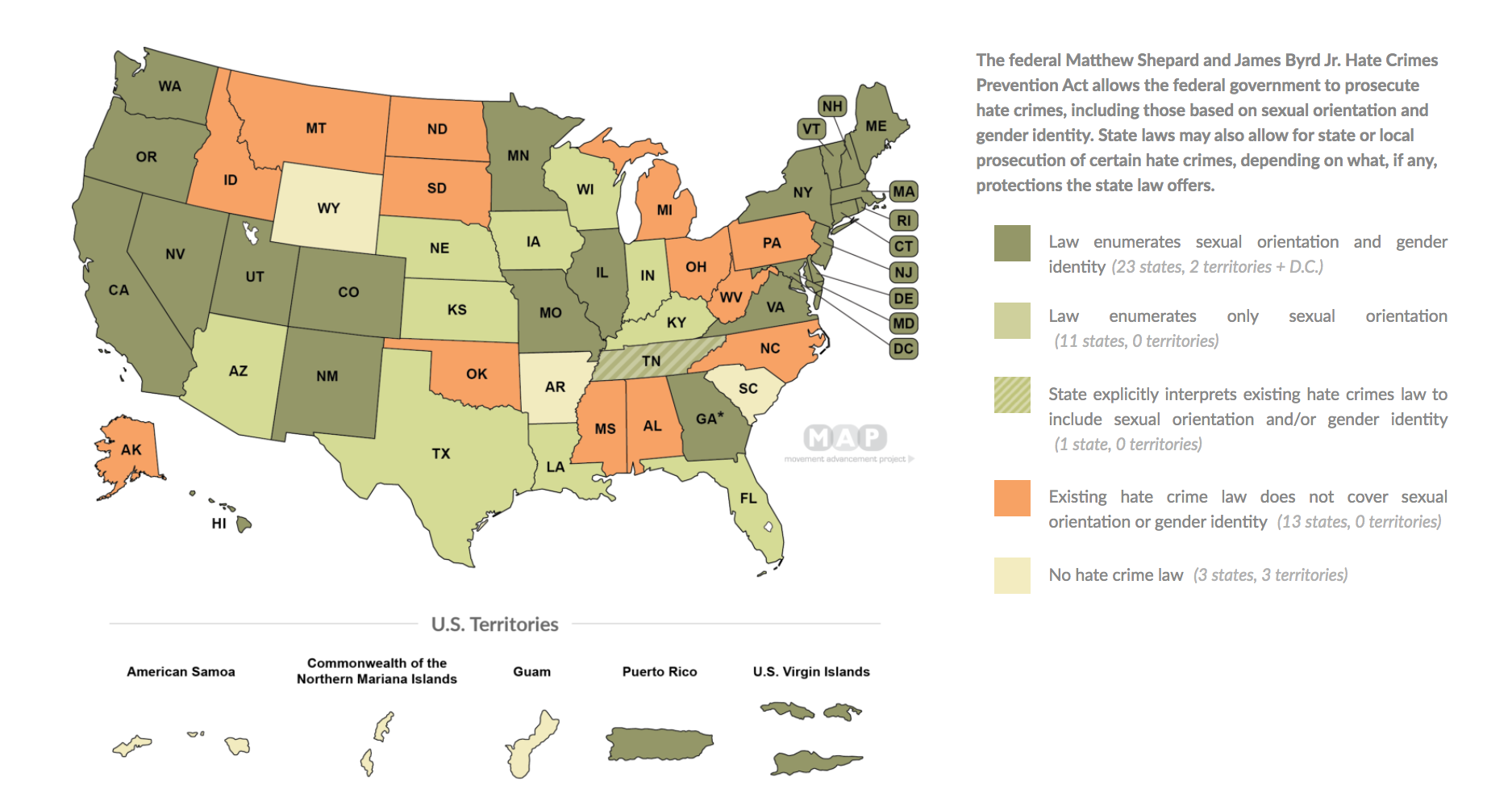

Federal laws address constitutional rights violations, but states have—or don’t have—their own specific hate-crime laws (Levin & McDevitt, 2002). Today, there are a wide range of laws regarding hate-crime protections across states, and they vary regarding protected groups, criminal or civil approaches, crimes covered, complete or limited data collection, and law enforcement training (Shively, 2005). As of 2019, nineteen states did not have any LGBT hate-crime laws, and twelve states had laws that covered sexual orientation but did not address gender identity and expression. Twenty states included both sexual orientation and gender identity in their hate-crime laws (Movement Advancement Project, n.d.). The majority of these laws were created in the first years of the 2000s, and gender identity and expression were included in the following years.

2.6.2.3 Debating Hate-Crime Laws

The arguments supporting hate-crime laws note that offenders’ acts promote the unequal treatment of not only individuals but also the broader communities that victims belong to, cause long-term psychological consequences for victims, and violate victims’ ability to freely express themselves (Cramer, et al, 2013) (Bessel, 2005) (Sullaway, 2004). The creation of laws serves to “form a consensus about the rights of stigmatized groups to be protected from hateful speech and physical violence” (Spade & Willse, 2000). This approach, however, centers on the perpetrator perspective and avoids a structural approach to oppression that acknowledges the numerous forms of bias and the overarching perpetuation of bias in society.

Many scholars have criticized the term hate crime for its erasure of the broader structures that support hate violence and instead place the blame for such acts solely on individuals assumed to be pathological and acting out of emotion (Ray and Smith, 2001)(Perry, 1999). Moreover, hate-crime laws primarily function at the symbolic level; crimes are reported at low rates, and statutes are not applied to such crimes by authorities (McPhail, 2000). Such laws focus not on prevention of crimes but rather on punitive measures to punish particular crimes.

With the existing high incarceration rates of LGBTQIA+ people as well as people of color, hate-crime laws support rather than challenge mass incarceration (Meyer, et al, 2017). Some activists argue for efforts to “build community relationships and infrastructure to support the healing and transformation of people who have been impacted by interpersonal and intergenerational violence; [and efforts to] join with movements addressing root causes of queer and trans premature death, including police violence, imprisonment, poverty, immigration policies, and lack of healthcare and housing” (Bassichis, et al, 2011).

No universal consensus about the role of hate-crime laws in furthering the acceptance and inclusion of LGBTQIA+ people in American society currently exists (Figure 2.6.). For many people, such laws carry with them an emphasis on the value of their lives and help further their sense of belonging. Others, particularly LGBTQIA+ activists engaged in broader social justice struggles, argue that such laws merely buoy a broken criminal justice system that cannot truly benefit the LGBTQIA+ community.

Figure 2.6. A map of state policy tallies for hate-crime laws. (Courtesy of the Movement Advancement Project.)

Figure 2.6. A map of state policy tallies for hate-crime laws. (Courtesy of the Movement Advancement Project.)

2.6.3 Licenses and Attributions for Re-Evaluating Policy

“Re-Evaluating Policy” by Alison S. Burke and Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “4.5 Re-Evaluating Policy” by Alison S. Burke in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

“2.6.2. LGBTQIA+d” by Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “Profile: Anti LGBTQ Hate Crimes in the United States:Histories and Debates” by Ariella Rotramel in LGBTQ+ Studies: An Open Textbook by James Aimers, Christ Craven, Marquis Bey, Kimberly Fuller, Rev. Miller Jen Hoffman, Thomas Lawrence Long, Jennifer Miller, Gesina Phillips. Clark A. Pomerleau, Christine Rodriguez, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, MDiv, MA, Ariella Rotramel, Shyla Saltzamn, Dara J. Silberstein, Marianne Snyder, PhD, MSN, RN, Lynne Stahl, Rachel Wexelbaum, Dr. Ryan J. Watson, Sarah R. Young is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 2.5. Stonewall Inn with Orlando Memorial used under CC-BY-SA Rhododendrites.

Figure 2.6. Equality Maps: Hate Crime Laws used under Fair Use by the Movement Advancement Project.