5.5 Positivist Criminology

If criminal behavior were merely a choice, the crime rates would more likely be evenly spread. However, when European researchers started to calculate crime rates in the nineteenth century, some places consistently had more crime from year to year. These results indicated that criminal behavior must be influenced by something other than choice and and must be related to other factors.

Positivism is the use of empirical evidence through scientific inquiry to improve society. Ultimately, positivist criminology sought to identify other causes of criminal behavior beyond choice based on measurement, objectivity, and causality (Hagan, 2018). Early positivist theories speculated that there were criminals and noncriminals and hoped to identify what causes made criminals.

In 1859 Charles Darwin wrote On the Origin of Species which outlined his observations of natural selection. A few years later, he applied his observations to humans in Descent of Man (1871) where he said that some people might be “evolutionary reversions” to an early stage of man. Although he never wrote about criminal behavior, others borrowed Darwin’s ideas and applied them to crime.

5.5.1 Biological and Psychological Positivism

Biological and psychological positivism theories assume there are fundamental differences that differentiate criminals from noncriminals and that these differences can be discovered through scientific investigations. Additionally, many early biological and psychological theories used hard determinism, which implies people with certain traits will be criminals.

Cesare Lombroso was a medical doctor in Italy when he had an epiphany. As he was performing autopsies on Italian prisoners, he started to believe many of these men had different physical attributes compared to law-abiding people. He also thought that these differences were biologically inherited. In 1876, five years after Darwin’s claim that some humans might be evolutionary reversions, Lombroso wrote The Criminal Man which said that one-third of all offenders were born criminals who were evolutionary throwbacks.

He identified a list of physical features he believed to deviate from the “normal” population. These included an asymmetrical face, monkey-like ears, large lips, receding chin, twisted nose, long arms, skin wrinkles, and many more, as seen in figure 5.4. Lombroso believed he could identify criminals simply by the way they physically looked. Even though his theory was later widely rejected, it is an example of the first attempt to explain criminal behavior scientifically.

5.5.1.1 Atavistic features image

Figure 5.4. An example of what were considered Atavistic features.

A few decades after Lombroso’s theory, Charles Goring took Lombroso’s ideas about physical differences and added mental deficiencies. In The English Convict, Goring claimed there were statistical differences in physical attributes and mental defects. The focus on mental qualities led to a new kind of biological positivism called the Intelligence Era. Alfred Binet, who created the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) Test, believed intelligence was dynamic and could change.

Unfortunately, many Americans at the time believed intelligence was fixed and could not change. H. H. Goddard, an early psychologist, took Binet’s well intentioned IQ test and used it to sort people into categories of “intelligence”. Those who scored too low were institutionalized, deported, or sterilized. He was an early advocate of sterilizing those who were mentally deficient. He especially wanted to target “morons,” who he said were just smart enough to blend in with the normal population. In 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell allowed the use of sterilization of those incarcerated people with disabilities based on the ideas of Goddard and other such psychologists.

Even after Lombroso, Goring, and Goddard, more contemporary research revealed that intelligence is at least as critical as race and social class for predicting delinquency (Hirschi & Hindelang, 1977). However, how intelligence is measured and defined is based on preconceived assumptions of intelligence. For example, is intelligence inherited? Is it related to the dominant culture? Or is it based more on the person’s environment? Each has at least some element of truth.

Modern science has revealed that biology plays a role in our behavior, but can’t say how or even how much. Studies of people who are twins or adopted have examined the nature-versus-nurture debate. Both play a role in our behavior, so perhaps the question ought to be “how do our biological differences interact with our sociological differences?”

What about criminal personalities like sociopaths and psychopaths? Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck, (1950) Polish-American criminologists determined there was no real criminal personality, but there are some interrelated personality characteristics. For example, there have been correlations between certain personality traits and criminal behavior: impulsivity, lack of self-control, inability to learn from punishment, and low empathy have all been linked to criminal behaviors.

But none of these personality characteristics are criminal on their own. However when a person has many of these personality characteristics, there seems to be a higher association with criminal behavior. Capsi, et al., (1994) found that constraint and negative emotionality, two super traits that contain a number of different characteristics, were “robust correlates of delinquency.”

Researchers have determined that biology and personality play a role in criminal behaviors, but they cannot say how much or to what degree. The characteristics of our social environment interact with our biology and personality. Human behavior is complex and it is difficult to determine the true causality of human actions.

5.5.2 The Chicago School

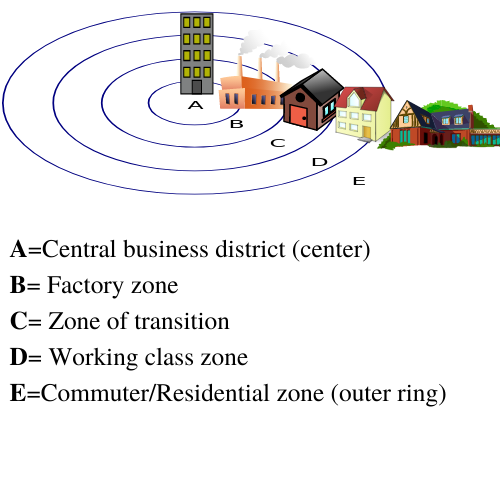

Biological and psychological positivism looked at differences between criminals and noncriminals. The Chicago School theories tried to detect differences between kinds of places where crime happens. In the 1920s and 30s, the University of Chicago pioneered the study of human ecology, which is the study of the relationship between humans and their environment. Robert Park (1925) viewed cities as “super-organisms,” comparing the city-human relationship to the natural ecosystems of plants and animals that share habitats. Ernest Burgess (1925) proposed concentric zone theory, which explained how cities grow from the central business district outward, as seen in figure 5.5.

5.5.2.1 Concentric Zones image

Figure 5.5. Concentric Zones – Urban Social Structures as Defined by Sociologist Ernest Burgess.

In 1942, Clifford Shaw and Henry McKay, both former students of Burgess, began to plot the addresses of juvenile court-referred male youths and noticed crime was not evenly spread over the entire city. They found the highest crime rates were at addresses located in the transition zone. Upon further investigation, they noticed three qualitative differences within the transition zone compared to the other zones. First, these areas were not zoned specifically for residential dwellings, meaning homes were scattered around industrial buildings and had little surrounding residential infrastructure (parks, schools, stores, etc.) areas which had the largest number of condemned buildings. When many buildings are in disrepair, population levels decrease. Second, the population composition was also different. The zone in transition had higher concentrations of foreign-born and African American heads of families. It also had a transient population. Third, the transitional zone had socioeconomic differences with the highest rates of welfare, lowest median rent, and the lowest percentage of family-owned houses. Interrelated, the zone also had the highest rates of infant deaths, tuberculosis, and mental illness.

Shaw and McKay believed the transition zone led to social disorganization. Social disorganization is the inability of social institutions to control an individual’s behavior. This disorganization meant that social institutions, like family, school, religion, or government, and community members could no longer agree on essential norms and values and made it difficult to solidify community bonds. A lack of community and social safety net is especially destabilizing for young people, creates a sense of hopelessness, and has been linked to increased crime rates.

Overall, Shaw and McKay were two of the first theorists to put forth the premise that community characteristics matter when discussing criminal behavior.

5.5.3 Licenses and Attributions for Positivist Criminology

Figure 5.4. I precursori di Lombrso is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.5 Burgess Model is in the Public Domain, adapted by Trudi Radtke.

“Positivist Criminology” by Sam Arungwa, Megan Gonzalez, and Trudi Radtke is adapted from “5.6. Positivist Criminology, 5.7 Biological and Psychological Positivism, and 5.8. The Chicago School” by Brian Fedorek in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity.