5.6 Other Modern Criminological Theories

Apart from classicalism and positivism, the following theories represent most of the modern criminological theories used by criminologists today.

5.6.1 Strain Theory

Strain theories assume people will commit crime because of strain, stress, or pressure that can come anywhere. Strain theories assume that human beings are naturally good but that bad things happen, which push people into criminal activity.

Emilé Durkheim (1897/1951) believed that economic or social inequality was natural and inevitable. He also believed that inequality and crime were not related unless there was also a breakdown of social norms. According to Durkheim, when there is rapid social change, social norms break down and society needs time to reevaluate “normal” behaviors. He also believed that social forces have a role in dictating human thought and behaviors and when they break down, society loses the ability to control or regulate individuals’ behaviors.

Other researchers like Robert K. Merton built on Durkheim’s ideas, but didn’t believe that inequality was natural or inevitable. Instead, Merton (1938) believed that many human behaviors originate in the idea and pursuit of the American Dream, which is a belief that anyone who works hard enough will be able to succeed and move upward in society. He also believed that the social structure of American society restricts some citizens from attaining that dream. The culturally approved way to achieve the American Dream is through hard work, innovation, and education.

However, Merton knew that some people and groups don’t have the same opportunities to achieve the American Dream. When a person’s desire to achieve the American Dream meets society’s barriers, the people unable to jump the barriers feel pressure or strain, and then feel that they are blocked from their goal.

Merton said that people who felt blocked from their goal by society’s structures developed one of five personality adaptations: conforming, innovating, ritualizing, retreating, or rebelling.

Conformists are the most common adaptation. The conformist accepts the goals of society and the means for achieving them, and as an example becomes a college student. The innovator accepts the goals of society but rejects the means of achieving them and thus innovates their own ways to meet society’s goals, and as an example becomes a drug dealer. The ritualists conform to the means but reject or are blocked from achieving the goals, and as an example becomes the person who has given up on the promotion, nice car, and so on, and simply punches the time clock to keep what they have. The retreatist gives up on both the goals and means, and withdraws from society, and as an example becomes the alcoholic, the drug addict, or the vagrant. Finally, the rebel rejects both the goals and means of society, but they want to replace them with new goals and means, and as an example becomes a vigilante.

Merton emphasized economic strains even though his theory could explain any strain. Albert Cohen (1955) claimed strain could come from a lack of status. He wanted to know why most juvenile crimes occurred in groups. His research showed that many youths, especially those in lower-class families, rejected education and other middle-class values. Instead, many teenagers believed that status and self-worth were more important. When these teens had no status, reputation, or self-worth, it led to severe strain. Cohen found that youths sometimes committed a crime to gain status among their peer group. If youths had no legitimate opportunities, they were likely to join gangs to pursue illegitimate opportunities to achieve financial success.

In 2006, Robert Agnew proposed a general strain theory that claimed strains come from myriad sources. Agnew defined strain as any event that a person would rather avoid. Three types of strains include the failure to achieve a desired environment/outcome (e.g., monetary, status goals). The removal of a desired environment/outcome (e.g., loss of material possessions, the death of family members), and experiencing an undesired environment/outcome (e.g., parental rejection, bullying, discrimination, and criminal victimization). The characteristics of some strains are more likely to lead to crime. A strain that feels unjust and important can produce pressure that leads to criminal coping mechanisms. People with poorly developed coping skills are more likely to commit a crime because strains lead to negative emotions such as anger, depression, and fear. This can create social control issues like having trouble in school, as well as promote social learning, like joining peers who also need to vent their frustration. In general strain theory, criminal behavior serves a purpose: to escape strain, stress, or pressure.

5.6.1.1 Activity: Coping Mechanism Example

Everyone feels stress and copes with stress, pressure, or shame differently. Shame can motivate us to change for the better. For example, if you did poorly on an exam, you may start to study more. When you feel stress, what do you do?

When I ask students how they deal with stress, many say that they go for a run or a walk, lift weights, cry, talk, or eat ice cream. These are healthy (maybe not eating too much ice cream) and prosocial coping mechanisms. When I feel stressed, I write.

5.6.2 Learning Theories

In the previous section, strain theories focused on social structural conditions that contribute to people experiencing strain, stress, or pressure. Strain theories explain how people can respond to these structures. Learning theories complement strain theories because they focus on the content and process of learning.

Early philosophers believed human beings learned through association. This means that humans are a blank slate and our experiences build upon each other. It is through experiences that we recognize patterns and linked phenomena. For example, ancient humans used the stars and moon to navigate. People recognized consistent patterns in the stars that enabled long-distance travel over land and sea.

5.6.2.1 Classical Conditioning

A few centuries later, Ivan Pavlov was studying the digestive system of dogs. His assistants fed the dogs their meals. Pavlov noticed that even before the dogs saw food, they began to salivate when they heard the assistants’ footsteps. The dogs associated the oncoming footsteps with the upcoming food. This type of learning is called classical conditioning as noted in figure 5.6.

Figure 5.6. An Example of Classical Conditioning – Pavlov’s Dogs Experiment.

The acquisition of this learned response occurred over time. Human beings most certainly learn via classical conditioning, but it is a passive and straightforward approach to learning. You may feel fearful when you see flashing blue lights in our rearview mirror, salivate when food is cooking in the kitchen, or dance when you hear your favorite song. You passively learn from these events paired with your experiences.

5.6.2.2 Operant Conditioning

B.F. Skinner (1937) was also interested in learning and his theory of operant conditioning transformed modern psychology. Operant conditioning is active learning where organisms learn to behave based on reinforcements and punishments. Using rats and pigeons, Skinner wanted animals to learn a simple task through reinforcements. A reinforcement is any event that strengthens or maximizes a behavior that should continue or increase. Positive reinforcement is the addition of something desirable and negative reinforcement is the removal of something unpleasant. For example, if you wanted more people to wear seatbelts, you would want to reinforce the behavior. A positive reinforcement is praise or a reward for buckling up. A negative reinforcement is the seat belt alarm that comes in newer cars. It rings until you buckle up and once you do, the ringing stops. Both examples reinforce the behavior, but in different ways.

Punishments are given if you want a behavior to stop or decrease. A positive punishment gives something unpleasant and a negative punishment takes something away. For example, parents who want their teenager to stop breaking curfew can punish the teen in two ways. A positive punishment is scolding. A negative punishment is taking away the teen’s driving privileges. Both punishments want to stop the breaking of curfew, but in different ways.

5.6.2.3 Activity: Punishment Exercise

How does the Criminal Justice System positively punish offenders? How does the Criminal Justice System negatively punish? Give examples of both.

5.6.2.4 Differential Association Theory

In 1947 American sociologist Edwin Sutherland offered a groundbreaking perspective of a micro-level learning theory about criminal behavior, which he called differential association theory. It tried to explain how age, sex, income, and social locations related to the acquisition of criminal behaviors (Sutherland, 1947). He presented his theory as nine separate, but related propositions, which were:

- Criminal behavior is learned.

- Criminal behavior is learned in interaction with other persons in a process of communication.

- The principal part of the learning of criminal behavior occurs within intimate personal groups.

- When criminal behavior is learned, the learning includes: a) techniques of committing the crime, which are sometimes very complicated, sometimes very simple; b) the specific direction of the motives, drives, rationalizations, and attitudes.

- The specific directions of motives and drives are learned from definitions of the legal codes as favorable or unfavorable. In some societies, an individual is surrounded by persons who invariably define the legal codes as rules to be observed. While in others he is surrounded by a person whose definitions are favorable to the violation of the legal codes.

- A person becomes delinquent because of an excess of definitions favorable to violation of law over definitions unfavorable to violation of the law. This is the principle of differential association.

- Differential associations may vary in frequency, duration, priority, and intensity. This means that associations with criminal behavior and also associations with anti criminal behavior vary in those respects.

- The process of learning criminal behavior by association with criminal and anti-criminal patterns involves all of the mechanisms that are involved in any other learning.

- While criminal behavior is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by those general needs and values, since noncriminal behavior is an expression of the same needs and values. (Sutherland, 1947)

Sutherland describes the content of what is learned, but also the process of how it is learned. Ultimately, he argued people give meaning to their situation and this meaning-making determines if they would obey or break the law. For Sutherland, this meaning-making explains how siblings who grow up in the same environment differ in their behavior.

5.6.2.5 Social Learning Theory

In the late 1990’s American criminologist, Ronald Akers, utilized both operant conditioning and differential association theory in his “social learning” or “differential reinforcement” theory. Akers’ theory was interested in the process of how criminal behavior is acquired, maintained, and modified through reinforcement in social situations and nonsocial situations. According to Aker’s “differential associations” refer to the people one comes into contact with frequently and “definitions” are the meaning a person attaches to his or her behavior. Those meanings can be general (i.e., religious, moral, or ethical beliefs that remain consistent) or specific (i.e., apply to a specific behavior like smoking or theft).

In this theory peers are the source of definitions and the most important source of social learning. “Differential reinforcements” refer to the balance between anticipated rewards or punishment and the actual reward or punishment. For example, if a juvenile vandalized a storefront, their friend’s praise may reinforce that behavior. If the juvenile sought more praise, they might continue vandalizing more property (the peers’ reactionary praise positively reinforced the behavior). Aker’s final concept was “imitation/modeling”. Akers argued that human beings could learn by observing how other people are rewarded and punished. Thus, some people may imitate other people’s behavior, especially if that behavior was rewarded (Akers, 1994).

Finally, there are theories that focus on the content of what is learned. Subcultural theories focus on the ideas of what is learned rather than the social conditions that foster these ideas. Residents who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods, like in the transitional zone, may learn things that people who live in affluent neighborhoods do. Some groups may internalize values that are conducive to violence or justify criminal behavior (Anderson, 1994). In other words, where you grow up influences what you learn about crime, police, government, or religion.

5.6.3 Control Theories

Control theories ask why more people do not engage in illegal behavior. Instead of assuming criminals have a trait or have experienced something that drives their criminal behavior, control theories assume people are naturally selfish, and, if left alone, will commit illegal and immoral acts. Control theories try to identify what types of controls a person may have that stops them from becoming uncontrollable.

Early control theorists argued that there are multiple controls on individuals. Personal controls are exercised through reflection and following prosocial normative behavior. Social controls originate in social institutions like family, school, and religious conventions. Jackson Toby (1957) introduced the phrase “stakes in conformity,” which is how much a person has to lose if he or she engages in criminal behavior. The more stakes in conformity a person has, the less likely they would be willing to commit crime. For example, a married teacher with kids has quite a bit to lose if he or she decided to start selling drugs. If caught, he could lose his job, get divorced, and possibly lose custody of his children. However, juveniles tend not to have kids nor are they married. They may have a job, but not a career. Since they have fewer stakes in conformity, they would be much more likely to commit crime compared to the teacher.

5.6.3.1 Activity: Parenting Exercise

Parenting can be a challenging responsibility. They Are supposed to teach children how to behave. Ideally, parents have control over their children in many ways.

- What are ways parents have “direct” control over their children?

- What are ways parents have “indirect” control over their children?

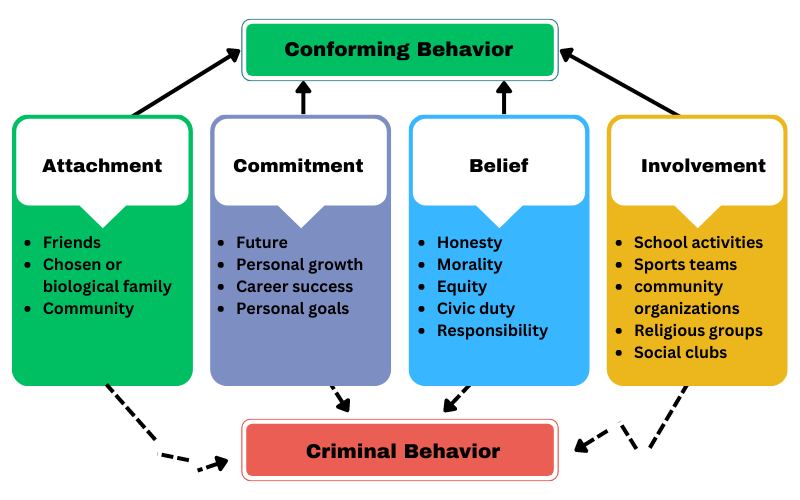

In 1969 Travis Hirschi argued that all humans have the propensity to commit crime, but those who have strong bonds and attachment to social groups like family and school are less likely to do so. Often known as social bond theory or social control theory, Hirschi presented four elements of a social bond: attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief.

Attachment refers to affection we have towards others. If we have strong bonds, we are more likely to care about their opinions, expectations, and support. Attachment involves an emotional connectedness to others, especially parents, who provide indirect control. Commitment refers to the rational component of the social bond. If we are committed to conformity, our actions and decisions will mirror our commitment. People invest time, energy, and money into expected behavior like school, sports, career development, or playing a musical instrument. These are examples of Toby’s “stakes in conformity” as shown in figure 5.7.

5.6.3.2 Stakes of Conformity (diagram)

Figure 5.7. Diagram of the Stakes of Conformity.

If people started committing a crime, they would risk losing these investments. Involvement and commitment are related. Since our time and energy are limited, Hirschi thought people who were involved in socially accepted activities would have little time to commit a crime. The observational phrase “idle hands are the devil’s worship” fits this component. Belief was the final component of the social bond. Hirschi claimed some juveniles are less likely to obey the law. Although some control theorists believed juveniles are tied to the conventional moral order and “drift” in and out of delinquency by neutralizing controls (Matza, 1964), Hirschi disagreed. He believed people vary in their beliefs about the rules of society. The essential element of the bond is an attachment. Eventually, Hirschi moved away from his social bond theory into the general theory of crime.

5.6.3.3 Activity: Hirschi Exercise

Hirschi believed strong social bonds made people less likely to commit a crime. The components of a social bond include attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief. Please describe each of the components of the social bond and explain how each applies to your educational journey. How can you be attached, committed, involved, and believe in higher education?

Michael Gottfredson and Travis Hirschi (1990) claimed their general theory of crime could explain all crime by all people. They argued the lack of self-control was the primary cause of criminal behaviors. They claim most ordinary crimes require few skills to commit and have an immediate payoff. Moreover, they claim, people who commit these ordinary crimes tend to be impulsive, insensitive to the suffering of others, short-sighted, and adventuresome. If true, these traits were established before the person started committing crimes and will continue to manifest throughout a person’s life. The root cause of low self-control is ineffective parenting. If parents are not attached to their child, supervise their child, recognize the child’s deviant behaviors, or discipline their child, the child will develop low self-control. Gottfredson and Hirschi claim self-control, or the lack thereof, is established by eight years old.

Control theories are vastly different from other criminological theories. They assume people are selfish and would commit crimes if left to their own devices. However, socialization and effective child-rearing can establish direct, indirect, personal, and social controls on people. These are all types of informal controls.

5.6.4 Critical Theories

Critical theories originated in the United States in the 1960s and 70s. Massive political turmoil inside and outside of the country created a generation of scholars who were critical of society and traditional theories of crime. These critical theories share five central themes (Cullen et al., 2018). First, to understand crime, one must appreciate the fusion between power and inequality. People with power, political and economic, have an enormous advantage in society. Second, crime is a political concept. Not all those who commit crime are caught, nor are those who are caught punished. The poor are injured the most by the enforcement of laws, while the affluent and powerful are treated leniently. Third, the criminal justice system and its agents serve the ruling class, the capitalists. Fourth, the root cause of crime is capitalism because capitalism ignores the poor and their living conditions. Capitalism demands profits and growth over values and ethical considerations. Fifth, the solution to crime is a more equitable society, both politically and economically.

5.6.5 Feminist Theories

Feminist criminology emerged in the 1970s as a response to the dominant male-centric perspective in criminology that had failed to account for the experiences of women in criminal justice systems. Feminist criminology is a critical framework that seeks to understand the relationship between gender, crime, and justice. This approach aims to highlight the gendered nature of crime and justice by acknowledging the ways in which gender-based inequality and power imbalances shape criminal behavior, victimization, and responses to crime.

Before we dive deeper it is important to begin with brief definitions of the different kinds of feminist theories. One central definition can be challenging, because as the Break Out Box below illustrates, there are many kinds of feminism, each with their own unique focus. However, there are features common to every type of feminism that we can use to establish a solid foundation when exploring feminist criminology. Primarily, feminism argues that women suffer discrimination because they belong to a particular sex category (female) or gender (woman), and that women’s needs are denied or ignored because of their sex. Feminism centers the notion of patriarchy in understandings of inequality, and largely argues that major changes are required to various social structures and institutions to establish gender equality. The common root of all feminisms is the drive towards equity and justice.

Different Feminisms

Feminist perspectives in criminology comprise a broad category of theories that address the theoretical shortcomings of criminological theories which have historically rendered women invisible (Belknap, 2015; Comack, 2020; Winterdyk, 2020). These perspectives have considered factors such as patriarchy, power, capitalism, gender inequality and intersectionality in the role of female offending and victimization. The six main feminist perspectives are outlined below.

Liberal Feminism

According to Winterdyk (2020) and Simpson (1989), liberal feminism focuses on achieving gender equality in society. Liberal feminists believe that inequality and sexism permeate all aspects of the social structure, including employment, education, and the criminal justice system. To create an equal society, these discriminatory policies and practices need to be abolished. From a criminological perspective, liberal feminists argue that women require the same access as men to employment and educational opportunities (Belknap, 2015). For example, a liberal feminist would argue that to address the needs of female offenders, imprisoned women need equal access to the same programs as incarcerated men (Belknap, 2015). The problem with the liberal feminist perspective is the failure to consider how women’s needs and risk factors differ from men (Belknap, 2015).

Radical Feminism

Radical feminism views the existing social structure as patriarchal (Gerassi, 2015; Winterdyk, 2020). In this type of gendered social structure, men structure society in a way to maintain power over women (Gerassi, 2015; Winterdyk, 2020). Violence against women functions as a means to further subjugate women and maintain men’s control and power over women (Gerassi, 2015). The criminal justice system, as well, becomes a tool utilized by men to control women (Winterdyk, 2020). It is only through removing the existing patriarchal social structure that violence against women can be addressed (Winterdyk, 2020).

Marxist Feminism

Like the radical feminist perspective, Marxist feminists view society as oppressive against women. However, where the two differ is that Marxist feminists see the capitalist system as the main oppressor of women (Belknap, 2015; Gerassi, 2015). Within a classist, capitalist system, women are a group of people that are exploited (Winterdyk, 2020). Exploitation in a capitalist system results in women having unequal access to jobs, with women often only having access to low paying jobs. This unequal access has led to women being disproportionately involved in property crime and sex work (Winterdyk, 2020). Like other Marxist perspectives, it is only through the fall of capitalism and the restructuring of society that women may escape from the oppression they experience.

Socialist Feminism

Social feminists represent a combination of radical and Marxist theories (Belknap, 2015; Winterdyk, 2020). Like radical feminists, they view the existing social structure as oppressive against women. However, rather than attributing these unequal power structures to patriarchy, they are the result of a combination of patriarchy and capitalism. Addressing these unequal power structures calls for the removal of the capitalist culture and gender inequality. Socialist feminists argue these differences in power and class can account for gendered differences in offending – particularly in how men commit more violent crime than women (Winterdyk, 2020).

Postmodern Feminism

Ugwudike (2015) outlines how postmodern feminism focuses on the construction of knowledge. Unlike other perspectives outlined above, which suggest there is “one reality” of feminism, postmodern feminists believe that the diversity of women needs to be highlighted when one considers how gender, crime and deviance intersect to inform reality (Ugwudike, 2015, p. 157). For postmodern feminists, they acknowledge the power differentials that exist within society, including gendered differences, and focus on how those constructed differences inform dominant discourses on gender. Of importance is the focus on “deconstructing the language and other means of communication that are used to construct the accepted ‘truth’ about women” (p. 158). Also of importance is the acknowledgement of postmodern feminism regarding how other variables, like race, sexuality, and class, influence women’s reality (Ugwudike, 2015).

Intersectional Feminism

Winterdyk (2020) notes that some academics add a sixth perspective. Intersectional feminists address the failure of the above perspectives to consider how gender intersects with other inequalities, including race, class, ethnicity, ability, gender identities, and sexual orientation (Belknap, 2015). Some of the above theories attempt to paint the lived experiences of all women as equal, whereas intersectional perspectives acknowledge that women may experience more than one inequality (Winterdyk, 2020). There is an inherent need to examine how these inequalities intersect to influence a women’s pathway to offending and/or risk of victimization. Recently, Indigenous Feminism has emerged as a critical discourse on feminist theory that considers the intersection of gender, race, as well as colonial and patriarchal practices that had been perpetuated against Indigenous women (Suzack, 2015).

Feminist activism has proceeded in four ‘waves’ (for a discussion of the waves of feminism, see A Timeline | Aesthetics of Feminism). The first wave of feminism began in the late 1800s and early 1900s with the suffragette movement and advocacy for women’s right to vote. The second wave of feminism started in the 1960s and called for gender equality and attention to a wide variety of issues directly and disproportionately affecting women, including domestic violence and intimate partner violence (IPV) employment discrimination, and reproductive rights. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the third wave focused on diverse and varied experiences of discrimination and sexism, including the ways in which aspects such as race, class, income, and education impacted such experiences. It is in the third wave that we see the concept of intersectionality come forward as a way to understand these differences. The fourth wave, our current wave, began around 2010 and is characterized by activism using online tools, such as Twitter. For example, the #MeToo movement is a significant part of the fourth wave. The fourth wave is arguably a more inclusive feminism – a feminism that is sex-positive, body-positive, trans-inclusive, and has its foundations in “the queering of gender and sexuality based binaries” (Sollee, 2015). This wave has been defined by “‘call out’ culture, in which sexism or misogyny can be ‘called out’ and challenged” (Munro, 2013).

5.6.5.1 The Emergence of Feminist Criminological Theories

We return to the second wave of feminism, in a time of social change, where feminist criminology was born. The emerging liberation of women meant newfound freedoms in the workforce and in family law, including the availability and acceptability of divorce, but these relative freedoms rendered gender discrimination even more visible. In the 1960s and 1970s, North American society specifically was full of unrest, with demonstrations and marches fighting for civil rights for Black Americans, advocating for gay and lesbian rights, and protesting the Vietnam War. Marginalized groups were calling out inequality and oppression, and demanding change. Feminist activism brought attention to the inequalities facing women, including their victimization, as well as the challenges female offenders faced within the criminal justice system. The breadth and extent of domestic violence, specifically men’s violence against women within intimate relationships, was demonstrated by the need for domestic violence shelters and the voices of women trying to escape violence. Conversations at the national level led to government-funded shelters as well as private donor funding from those who saw the need for safe havens from abuse. At the same time, the historic and systemic trauma of women involved in the criminal justice system as offenders was being recognized, including attention to their histories of abuse, poverty, homelessness, and other systemic discriminations. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, feminist scholars recognised the absence of women within criminological theory; more specifically, as Chesney-Lind and Faith (2001, p. 287) highlight, feminist theorists during this time “challenged the overall masculinist nature of criminology by pointing to the repeated omission and misrepresentation of women in criminological theory.”

Feminist criminologists have criticized mainstream criminological theories like Merton’s strain theory and social learning and differential association theories for their male-centered approach and lack of consideration for the gendered nature of crime (Wang, 2021). However, some feminist criminologists argue that these theories can still be utilized if they are modified to account for the predictors of crime in both men and women. For instance, Agnew’s general strain theory has attempted to incorporate a more comprehensive range of sources of strain into the theory, including relationship strains and negative life experiences, which are significant predictors of female delinquency. Additionally, life course theories present an opportunity for a gendered exploration of women’s criminality by examining life events that may alter the pathways from criminal to noncriminal behavior, such as childbirth.

5.6.5.2 Practicing Feminist Criminology

Feminist criminology employs a range of research methods, including qualitative research, statistical analysis, and critical discourse analysis. Qualitative research methods, such as interviews and focus groups, are commonly used to gather rich data on women’s experiences of crime, victimization, and justice. Statistical analysis is used to analyze large-scale datasets and identify patterns and trends in gendered crime and justice. Critical discourse analysis is employed to analyze language and power relations in legal and policy documents to uncover the ways in which gendered power imbalances shape criminal justice policy.

Feminist criminology has matured both in scholarship and visibility since its emergence in the 1970s. Feminist scholars have produced a rich body of literature that has challenged the dominant male-centric perspective in criminology and highlighted the gendered nature of crime and justice. Feminist criminology has also gained greater visibility in mainstream criminology and criminal justice policy, with feminist scholars engaging in policy debates and advocating for reforms that address gender-based inequality in the criminal justice system.

5.6.5.3 Activity: Gender and Crime Exercise

Write about how you were raised and how gender roles were reinforced through school, family, culture, or religion etc. Do you think men are more criminal because of their biology or because of cultural expectations of men versus women? You should support your claims with personal, vicarious, or well-known examples.

5.6.6 Social Reaction Theories

Social reaction theories concentrate on those people or institutions who label offenders, react to offenders, and want to control offenders. Social reaction theories emphasize how meanings are constructed through words, which carry power and meaning.If someone is labeled a criminal, that label carries meaning for other people. These meanings are culturally created through interactions with peers.

Not everyone who commits a crime is labeled as a criminal. Why? Labeling theories try to explain this phenomenon. In general, labeling theorists point to the social construction of crime, which varies over time and place. For instance, marijuana use is federally prohibited, but more and more states are legalizing recreational use. The same behavior can be legal in Oregon but illegal in Texas. Furthermore, labeling theorists emphasize the effects of being labeled and treated as a criminal. If a person is given a label, they may adopt that label. John Braithwaite (1989) applied some of these ideas in his theory of reintegrative shaming, which says that shaming can be reintegrative or stigmatizing. Reintegrative shaming centers on forgiveness, love, and respect. Ideally, we want to reintegrate the person back into the community by removing the label. However, in some societies, like the United States, stigmatizing shaming reigns supreme. Stigmatizing shaming uses formal punishment, which weakens a person’s bond to his or her community. It is counterproductive and tends to shun the offender. For example, in some states, convicted offenders are required to self-identify as a felon on job applications. Even though they may have served their time in prison, they are required to continue to label themselves as a criminal. Stigmatizing shaming propels people toward crime and reintegrative shaming seeks to correct the behavior through respect and empathy.

5.6.7 Licenses and Attributions for Other Modern Criminological Theories

Figure 5.6. Pavlov’s Classical Conditioning Diagram is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 5.7. The Stakes of Conformity by Trudi Radtke is in the Public Domain.

“5.6 Other Modern Criminological Theories” by Sam Arungwa, Megan Gonzalez and Trudi Radtke is adapted from “5.9. Strain Theories, 5.10. Learning Theories, 5.11. Control Theories, 5.12. Other Criminological Theories” by Brian Fedorek in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

“5.6.5.1 The Emergence of Feminist Criminological Theories” by Trudki Radke and Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “11.1 Foundations of Feminist Criminology” by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson; Dr. Jennifer Kusz; Dr. Tara Lyons; and Dr. Sheri Fabian in Introduction to Criminology, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.