7.3 Structure of the Dual Court Systems

Each state has two parallel court systems: the federal system and the state’s own system. This two-part structure results in at least 51 legal systems: the fifty created under state laws and the federal system created under federal law. Additionally, there are court systems in the U.S. Territories, and the military has a separate court system. Next, we will consider how the different court systems are structured.

The state/federal court structure is sometimes called the dual court system. State crimes, created by state legislatures, are prosecuted in state courts concerned primarily with applying state law. Federal crimes, created by Congress, are prosecuted in the federal courts, which are concerned primarily with applying federal law. As discussed in table 7.1, a case can sometimes move from the state system to the federal system, depending on the type of case.

|

Dual Courts |

Federal Courts |

State Courts |

|---|---|---|

|

Highest Appellate Court |

U.S. Supreme Court (Justices) (Note: Court also has original/trial court jurisdiction in rare cases) (Note: Court will also review petitions for writ of certiorari from State Supreme Court cases). |

State Supreme Court (Justices) |

|

Intermediate Appellate Court |

U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (Judges) |

State Appellate Court (e.g., Oregon Court of Appeals) (Judges) |

|

Trial Court of General Jurisdiction |

U.S. District Court (Judges) (Note: this court will review petitions for writs of habeas corpus from federal and state court prisoners) |

Circuit Court, Commonwealth Court, District Court, Superior Court (Judges) |

|

Trial Court of Limited Jurisdiction |

U.S. Magistrate Courts (Magistrate Judges) |

District Court, Justice of the Peace, Municipal Courts (Judges, Magistrates, Justices of the Peace) |

Table 7.1. Dual Court System Structure

7.3.1 The Federal Court System

Article III of the U.S. Constitution established a United States Supreme Court and granted Congress power to adopt a lower court system. The Constitution states the “judicial Power of the United States shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” In line with this authority, Congress immediately created a lower federal court system in 1789 (The Judiciary Act, 1789). The lower federal court system has been expanded over the years, and chances are that Congress will continue to exercise its power to modify the court system as the need arises. Table 7.2 shows the difference between the federal court system and the state court system in the selection of judges and the types of cases heard.

7.3.1.1 Selection of Judges

|

The Federal Court System |

The State Court System |

|---|---|

|

The constitution states that federal judges are to be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. They hold office during good behavior, typically, for life. Through Congressional impeachment proceedings, federal judges may be removed from office for misbehavior. |

State court judges are selected in a variety of ways, including

|

7.3.1.2 Types of Cases Heard

|

The Federal Court System |

The State Court System |

|---|---|

|

State courts are the final arbiters of state laws and constitutions. Their interpretation of federal law or the U.S. Constitution may be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court may choose to hear or not to hear such cases. |

Table 7.2. Judges Selection & Cases.

7.3.1.3 Dig Deeper

This box contains important links to additional materials. Click on the links to learn more about the relationship between the state and federal courts.

- View the authorized federal judgeships at http://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/allauth.pdf.

- Trace the history of the federal courts at https://www.fjc.gov/history/timeline/8276.

- Trace the history of the subject matter jurisdiction of the federal courts here https://www.fjc.gov/history/timeline/8271.

- View cases that shaped the roles of the federal courts at https://www.fjc.gov/history/timeline/8271.

- Trace the administration of the federal courts at https://www.fjc.gov/history/timeline/8286.

7.3.2 U.S. Supreme Court

The U.S. Supreme Court (Court), located in Washington, D.C., is the highest appellate court in the federal judicial system. Nine justices sitting en banc, as one panel, together with their clerks and administrative staff, make up the Supreme Court (figure 7.5). You can view the biographies of the current U.S. Supreme Court Justices here: https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/biographies.aspx.

The Supreme Court’s decisions have the broadest impact because they govern the state and federal judicial systems. Additionally, this Court influences federal criminal law because it supervises the activities of the lower federal courts. The nine justices can determine what the U.S. Constitution permits and prohibits, and they are most influential when interpreting it. Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Robert H. Jackson stated in Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 433, 450 (1953), “We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final.” In other words, Jackson seems to emphasize that the Supreme Court is often the final word on major legal decisions, making the Court’s decisions authoritative and indisputable. However, there are rare instances when the court’s decision can be changed. For instance, Congress can sometimes enact a new statute to change the Court’s holding.

Figure 7.5. Current U.S. Supreme Court From left to right: Associate Justices Amy Coney Barrett, Neil M. Gorsuch, Sonia Sotomayor, and Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., and Associate Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson, Samuel A. Alito, Jr., Elena Kagan, and Brett M. Kavanaugh.

The Court has a discretionary review over most cases brought from the state supreme courts and federal appeals courts. In a process called a petition for the writ of certiorari (rule of four), four justices must agree to accept and review a case, which happens in roughly 10 percent of the cases filed. Once accepted, the Court schedules and hears oral arguments on the case, then delivers written opinions. Over the past ten years, approximately 8,000 petitions for writ of certiorari have been filed annually. It is difficult to guess which cases the court will accept for review. However, a common reason the court accepts to review a case is that the federal circuit courts have reached conflicting results on important issues presented in the case (UScourts.gov – Writs of Certiorari, 2022).

Take a more in-depth look at the U.S. Supreme Court: Supreme Court Procedures | United States Courts

When the U.S. Supreme Court acts as a trial court it is said to have original jurisdiction, which rarely happens. One example is when one state sues another state. The U.S. Constitution, Art. III, §2, sets forth the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, and provides the necessary strict restrictions on cases allowed (Uscourts.gov/Supreme Court Procedures, 2022). This statutory restriction allows the highest court to focus on the most important cases.

7.3.2.1 Changes to the U.S. Supreme Court

Any change to the U.S. Supreme Court, as the highest court in America, is highly anticipated and newsworthy. This past decade has seen several important changes that impact diversity, equity, and inclusion in the American judicial court systems.

7.3.2.2 Diversity in the Supreme Court

In 2022, President Joe Biden made news when he announced his intention to nominate a Black woman to the U.S. Supreme court. Despite the strong pushback from Senate Republicans, the president fulfilled his campaign promise by nominating Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. Before her confirmation to the Supreme Court, Jackson rose through the judicial ranks, making her one of the most qualified for the job. She had previously been promoted to the country’s “second-highest court,” known as the D.C. Circuit (Howe, Amy L. 2022, February 1). She is also the first public defender to serve on the supreme court (Pilkington, E. 2022, April 7). A divided U.S. Senate voted to confirm her nomination. On June 30, 2022, Jackson was sworn in as the 116th Supreme Court justice and the first Black woman to serve on this highest court in America. (Bustillo, X. (2022, June 30. Ketanji Brown Jackson was sworn in as the first Black woman on the Supreme Court. NPR).

7.3.2.3 Roe v. Wade and the Supreme Court

Figure 7.6. Protests at the Supreme Court on the day Roe v. Wade was overturned.

On June 24, 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 decision that affirmed the constitutional right to abortion (figure 7.6). The supreme court has been leaning more conservatively for the last few years. But the most recent ruling indicates that the current supreme court is the most conservative it has ever been for almost a century (Totenberg, N. 2022, July 6). Researchers and scientists are scrambling to warn about the many social, economic, and public health consequences of this anti-abortion ruling. On the political front, this abortion issue is bound to further the conflict and divide that already exists in America.

7.3.2.4 Packing the Supreme Court

The supreme court was originally designed to remain impartial and above politics. But over the last few years, there have been a number of rulings from the court that seem partisan (Lazarus, S. 2022, March 23). One of the many proposals to balance the conservative-leaning U.S. Supreme Court is known as “court-packing.” This highly controversial method involves adding more supreme court justices to try and equalize the number of liberal and conservative judges (Noll, D. What Is Court Packing?). See figure 7.7 for a short video explaining how the court-packing process evolved over the years. While the “court-packing” idea remains controversial, many proponents and Democrats felt that the recent U.S. Supreme court appointments made by Republican presidents amount to court-packing (Calmes, J. 2021, June 22).

Figure 7.7. “How calls to ‘pack’ the Supreme Court evolved over the years [Youtube Video].”

7.3.2.4.1 Dig Deeper

Watch these videos to learn more about the Supreme Court:

Figure 7.8. “The Supreme Court Is Unpopular. But Do Americans Want Change? | FiveThirtyEight [Youtube Video].”

Figure 7.9. ”Court Packing Explained by a Constitutional Attorney [Youtube Video].”

7.3.2.5 U.S. Courts of Appeal

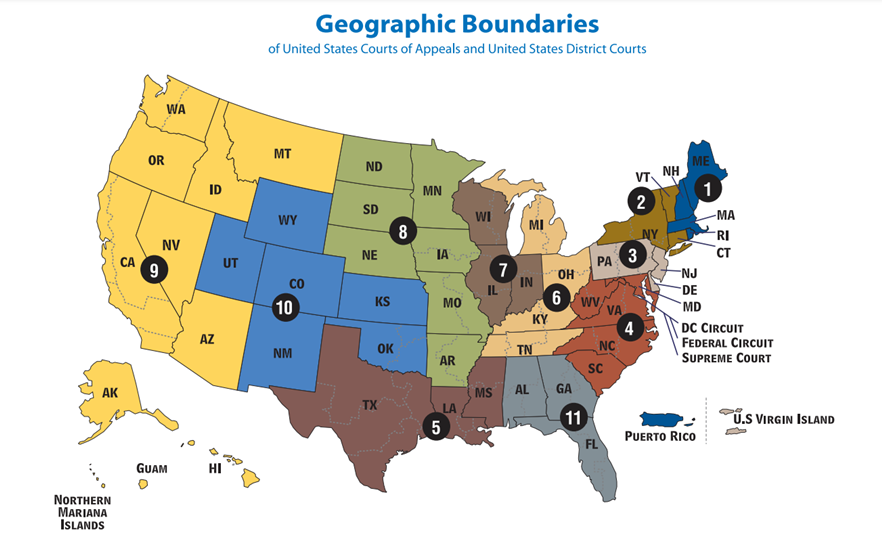

Ninety-four judicial districts comprise the 13 intermediate appellate courts (figure 7.10.) in the federal system known as the U.S. Courts of Appeals, sometimes referred to as the federal circuit courts. These courts hear challenges to lower court decisions from the U.S. District Courts located within the circuit, as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies, such as the social security courts or bankruptcy courts.

Figure 7.10. Geographical jurisdiction of the U.S. Courts of Appeals

There are twelve circuits based on locations. One circuit has nationwide jurisdiction for specialized cases, such as those involving patent laws and cases decided by the U.S. Court of International Trade and the U.S. Court of Federal Claims. The smallest circuit is the First Circuit with six judgeships, and the largest court is the Ninth Circuit, with 29 judgeships.

Appeals court panels consist of three judges. The court will occasionally convene en banc and only after a party, that has lost in front of the three-judge panel, requests review. Because the Circuit Courts are appellate courts that review trial court records, they do not conduct trials or use a jury. The U.S. Courts of Appeal trace their existence to Article III of the U.S. Constitution.

7.3.2.6 U.S. District Courts

The U.S. District Courts, also known as “Article III Courts,” are the main trial courts in the federal court system. Congress first created these U.S. District Courts in the Judiciary Act of 1789. Now, 94 U.S. District Courts, located in the states and four territories, handle prosecutions for violations of federal statutes. Each state has at least one district, and larger states have up to four districts. The name of district courts reflects their location (for example, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California). The district courts have jurisdiction over all prosecutions brought under criminal and civil suits brought under federal statutes. A criminal trial in the district court is presided over by a judge who is appointed for life by the president with the consent of the Senate. Trials in these courts may be decided by juries.

Although the U.S. District Courts are primarily trial courts, district court judges also exercise an appellate-type function in reviewing petitions for writs of habeas corpus brought by state prisoners. Writs of habeas corpus are claims by state and federal prisoners who allege that the government is illegally confining them in violation of the federal constitution. The party who loses at the U.S. District Court can appeal the case in the court of appeals for the circuit in which the district court is located. These first appeals must be reviewed, and thus are referred to as appeals of right.

7.3.2.7 U.S. Magistrate Courts

U.S. Magistrate Courts are courts of limited jurisdiction, which means they do not have full judicial power. Congress first created the U.S. Magistrate Courts with the Federal Magistrate Act of 1968. Under the Act, federal magistrate judges assist district court judges by conducting pretrial proceedings, such as setting bail, issuing warrants, and conducting trials of federal misdemeanor crimes. More than five hundred Magistrate Judges work on more than a million cases each year.

U.S. Magistrate Courts are “Article I Courts” as they owe their existence to an act of Congress, not the Constitution. Unlike Article III judges, who hold lifetime appointments, Magistrate Judges are appointed for eight-year terms.

7.3.3 Licenses and Attributions for Structure of the Dual Court Systems

“Structure of the Dual Court Systems” by Sam Arungwa is adapted from “7.3. Structure of the Courts: The Dual Court and Federal Court System” by Lore Rutz-Burri in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 7.5. ”Current U.S. Supreme Court” by the Supreme Court of the United States is in the Public Domain.

Figure 7.6. “2022.06.24 Roe v Wade Overturned – SCOTUS, Washington, DC USA 175 143227” by Ted Eytan, Flickr is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 7.7.“How calls to ‘pack’ the Supreme Court evolved over the years” by the Washington Post is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 7.8. “The Supreme Court Is Unpopular. But Do Americans Want Change? | FiveThirtyEight [Youtube Video].”

Figure 7.9. ”Court Packing Explained by a Constitutional Attorney [Youtube Video].”

Figure 7.10. “Geographic Boundaries of United States Courts of Appeals and United States District Courts” is in the Public Domain.