8.2 Philosophies of Punishment

This section will highlight the history and function of the corrections in the justice system. It will relate the three current goals of corrections, which are to:

- punish the offender,

- protect society, and

- rehabilitate the offender.

Within these goals, it will look at and compare the philosophies of punishment over time and how ideologies have changed a result. The section wraps up with a comparison of the eras of corrections.

8.2.1 A Brief History of Punishment

Feeling safe and secure in person and home is arguably one of the most discussed feelings in our nation today. The fear of crime influences how we think and act day to day, and has throughout our history. This has caused great fluctuation in the United States in regards to how we punish people who are convicted of violating the law. Punishment is a penalty imposed on an individual convicted of a crime or law violation. This comes, in part, from the will of the people, which is then carried out through the legislative process, and converted into sentencing practices. People have differing views, or ideologies, on why others should be punished, and how much punishment they should receive. In this section, we will dive into a brief history of these ideologies and the various eras related to corrections. These correctional ideologies, or philosophical underpinnings of punishment, have been prevalent throughout the history of the United States and they have been imposed by governments and societies worldwide since the beginning of humankind as a way to uphold justice and impose punishment. This section details basic concepts of some of the more frequently held punishment ideologies, which include retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation.

8.2.2 Ideologies of Punishment

Two news stories pop up on your feed. In the first story, a man living in your city is described as a convicted sex offender. His neighbors are picketing in front of his house, voicing their displeasure that he is allowed to live there. The video shows how angry the neighborhood is and you can see the frustration and anger on the people’s faces.

The second story is about a woman who was detained for stealing food from a local grocery store, apparently to feed her children. She is shown in the back of a police car. The store manager is interviewed and says he is offering to donate the food to her so that she does not have to spend time in jail or get into any more trouble.

How do these two stories make you feel? Is it the same feeling for each story? Does one of these stories make you feel more afraid of crime? More angry or upset? Which one? Who deserves to get punished more? How much punishment should they get? The answers to questions like these flood our thoughts as we see stories like this, and when we hear about crime, in general. These questions and feelings are normal. It is this process that generates our own personal punishment ideology.

Now, which one of these two individuals has actually committed a crime? Technically, the woman is the person who has broken the law. Our perceptions of punishment can be influenced by the narrative we hear online or from others.

In this section, we will reference forward-looking ideologies and backward-looking ideologies. Forward-looking ideologies are designed to provide punishment, but also to reduce the level of recidivism (reoffending) through some type of change, while the backward-looking approach is solely for the punishment of past actions. The change in ideologies and in how society views punishment is a shift that occurs over time and is impacted by the dominant culture, politics, and even religion.

8.2.2.1 Retribution

Retribution, arguably the oldest of the ideologies of punishment, is punishment which is imposed on a person as revenge or vengeance for a criminal act and the only backward-looking philosophy of punishment. That is, the primary goal of retribution is to ensure that punishments are proportionate, or equal, to the seriousness of the crimes committed regardless of the individual differences between the offenders and their circumstances, other than mens rea and an understanding of moral culpability. Thus, retribution focuses on the past offense, rather than the individual who offended. People committing the same crime should receive a punishment of the same type and duration that balances out the crime that was committed.

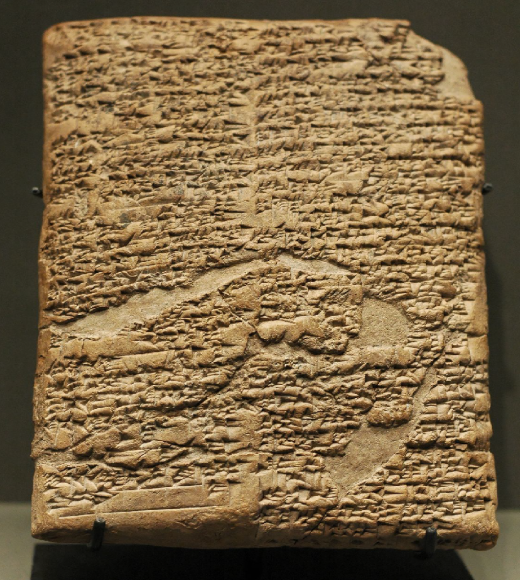

It is argued as the oldest of the main punishment ideologies because it comes from a basic concept of revenge. This concept of vengeance means that if someone perceives harm, they are within their right to retaliate at a proportional level. This idea that retaliation against a transgression is allowable has ancient roots in the concept of lex talionis, which is the law of retaliation. A person who injures someone should be punished with a similar amount of harm. This concept was developed in early Babylonian law and around 1780 B.C.E. the Babylonian Code, or the Code of Hammurabi, was written. It is the first attempt at written laws. These laws, pictured in figure 8.1., represent a retributive approach to punishment.

Figure 8.1. The Hammurabi Code.

The retributivist philosophy also calls for any suffering beyond what was originally intended during sentencing to be removed. This is because the dosage of punishment is the core principle of retribution: individuals who commit the same crime must receive the same punishment. The concept of retribution was violent and it laid the foundation for physical punishments to resolve the actions of another. We see this concept still applied today in the imposition of capital punishment, or the death penalty. This is one form of retribution that many U.S. States and the federal government still use today to impose punishment to those who have murdered other individuals. As we continue forward in the history of punishment, we will see some changes to the perceptions of how society reacts to crime. This includes the changing views of punishment, to include punishment ideologies that are more forward-looking.

8.2.2.2 Deterrence

From Hammurabi, deterrence is the next major punishment ideology. Rooted in the concepts of classical criminology referenced in Chapter 5, deterrence is designed to punish current behaviors, but also ward off future behaviors through sanctions or threats of sanctions. Deterrence can be focused on a group or on one individual. The basic concept of deterrence is to discourage individuals from offending by imposing punishment sanctions or threatening such sanctions.

Deterrence can be split into two distinct categories: general and specific. General deterrence is the idea that when someone commits an offense, they will be punished. In this way, the group imposing the punishment determines the ideals of the community and says that future criminal acts will be punished. Specific deterrence tries to teach the individual a lesson and make them better so that they will not recidivate. By punishing or threatening to punish the individual, it is assumed they will not commit a crime again. This is what makes deterrence a forward-looking theory of punishment.

Some other principles of deterrence to discuss in brief are marginal, absolute, and displacement. Marginal deterrence works on the principle that the action itself is only reduced in amount by the individual committing the offense, not removed completely. For example, if a person sees a police car sitting on the side of the freeway and they are driving 70 mph, they might slow to 58 mph. Technically, they may still be breaking the law, yet their level of criminal behavior has been reduced.

Absolute deterrence believes that by creating a police force, all crime will be removed. Today, we know this is false. There is little to no evidence to support that all crime can be deterred within a specific area or even in general.

Displacement deterrence argues that crime is not deterred, but is shifted by time, location, or the type of crime committed. For example, instead of someone stealing cars on the weekend, they may sell drugs during the day. Although the weekend crime carjacking rate would decrease in this scenario, the daily drug trade would increase.

In order for all of these principles of deterrence to work, the society must have an idea of the level of punishment they will receive. For this theory to be effective, individuals must have three key elements: free will, rationality, and felicity. Free will means that everyone has the ability to make choices about their future actions, like choosing when to offend and not to offend. They must also have some ability to think rationally and to see what the outcomes of their choices will be. Felicity is the idea that they must desire more pleasurable things than harmful ones. Thus, it is more probable that crime will be deterred if all three of these elements are in place within a society. This is both a strength and weakness of the deterrence theory.

These concepts, along with the classical criminology concepts discussed in Chapter 5, were cornerstones to the works of Beccaria. Many of his concepts shaped the U.S. Bill of Rights. If deterrence is to work, the ideology of the punishment is what should drive this goal of corrections.

Today, we have a better understanding of the effectiveness of deterrence. It does appear to work for low-level offenses and for individuals who are generally prosocial. However, the overall effect of deterrence is limited.

8.2.2.2.1 Dig Deeper

For more details on deterrence, see the National Institute of Corrections’ Five Things About Deterrence.

8.2.2.3 Incapacitation

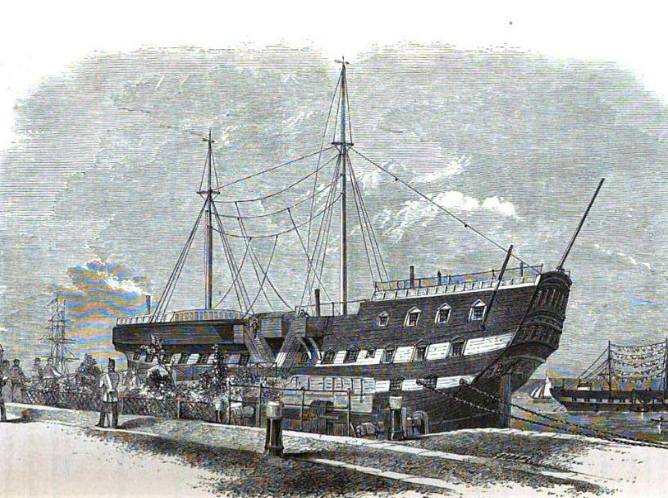

Rooted in the concepts of banishing individuals from society, incapacitation is the removal of an individual from society for a set amount of time so they cannot commit crimes. In British history, this often occurred on hulks, as seen in figure 8.2. Hulks were large ships which carried convicted criminals to other places so they would be unable to commit crimes in their community any longer.

Figure 8.2. The Warrior prison ship.

In the 1970s, punishment became much more of a political topic in the United States, and perceptions of the fear of crime became important. Lawmakers, politicians, and others began to campaign on their toughness on crime, using the fear of crime and criminals to benefit their agendas to impose punitive prison sentences. This is considered collective incapacitation, or the incarceration of large groups of individuals to remove their ability to commit crimes for a set amount of time in the future.

Since this time, and exacerbated in the 1980s and 1990s, there has been the increasing use of punishment by prison sentences. Thus, we saw a 500% increase in the prison population between 1980 and 2020 (Ghandnoosh, 2022). The politicization of punishment increased the overall incarcerated populations in two ways. First, by allowing decision makers more discretion, as a society, we have gotten tougher on crime. In turn, more people are now being sentenced to prison that may have gone to specialized probation or community sanction alternatives otherwise. Second, these same attitudes have led to harsher and lengthier punishments for certain crimes. Individuals are being sent away for longer sentences, which has caused the intake-to-release ratio to change, thus creating enormous buildups of the prison population. We will cover more on this topic in Chapter 9, specifically how these buildups have disproportionately affected minority populations.

The incapacitative ideology followed this design for several decades, but in the early 1990s, three-strike policies were implemented that would target individuals more specifically based on prior offenses or crimes committed. These selective incapacitation policies would incarcerate an individual for greater lengths of time if they had prior offenses. These policies incarcerated certain individuals for longer periods of time than others, even if they had committed the same crime. Thus, it removed their individual ability to commit crimes in society for greater periods of time as they were incarcerated.

There are mixed feelings about selective and collective incapacitation. Policymakers promote incapacitation by giving examples of locking certain individuals away in order to help calm the fear of crime. Others, like Blokland and Nieuwbeerta (2007), have stated that there is little evidence to suggest that this solves the problem. Selective incapacitation has evolved to include tighter crime control strategies that target individuals who repeat the same offenses. Others opt for tougher community supervision options to keep individuals under supervision longer. In summary, we have seen a shift from collective incapacitation, to a more selective approach.

After learning about retribution, deterrence, and incapacitation, we are left with questions: do they work? And at what cost? Are there other methods that seem the same or are more effective than the ones already in practice? This takes us to the last of the four main punishment ideologies: rehabilitation.

8.2.2.4 Rehabilitation

Although not as old as some of the older ideologies, rehabilitation is not a new concept. Rehabilitation is the ideology of helping individuals who have committed crimes change their behavior through interventions, treatment, therapy, education, and training in order to help them reenter society.

Rehabilitation has taken different forms in the United States. At one time, society considered people who commit crimes to be out of touch with God. One of America’s earliest prisons was designed to enhance incarcerated individuals’ connection with God. The Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, opened in 1829 and included outside reflection yards so individuals could look up to God for penance.

8.2.2.4.1 Dig Deeper

To see more about this prison, check out The Eastern State Penitentiary.

Reformatories were another type of correctional facility but with a focus on rehabilitation. The reform movement tried to rehabilitate the individual through more humane treatment, to include basic education, religious services, work experience, and general reform efforts. This was done in an effort to reform individuals, thus allowing them to come back to society. The Elmira Reformatory in Elmira, New York, seen in figure 8.3, was one of the earliest efforts of the reform ideal and many prisons built in the United States were based on this reformatory.

Figure 8.3. The Elmira Reformatory.

Rehabilitation has also included medical approaches. Incarcerated individuals were viewed as sick and in need of medical cures. This medical approach, while less common, is still used in some areas today. As of November of 2021, in the United States six states and one territory included the use of testosterone-inhibiting medications as a treatment for individuals convicted of sex offenses being considered for early release.

Rehabilitation as an ideology has its critics. Many see it as being soft on individuals who have been convicted of committing crimes. There are several examples that suggest rehabilitation is ineffective in some cases. For example in 1974, Robert Martinson reviewed more than 230 programs and concluded that “With few and isolated exceptions, the rehabilitative efforts that have been undertaken so far have had no appreciative effect on recidivism” (p. 25). This report caused many policymakers to turn to more punitive ideologies.. However, it did prompt some researchers to ask more detailed questions about why rehabilitation was not working, including critical questions about measurement of outcomes, evaluation of specific rehabilitative programs, and attempts to understand outcomes for individuals involved in the justice system. The answers to these questions became the principles of effective intervention that are the cornerstone of modern rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation is the only one of the four main ideologies that most comprehensively attempts to address current goals of corrections: punishing the offender, protecting society, and rehabilitating the offender. Certainly, all four ideologies address the first two goals, punishment and societal protection. However, the goal of rehabilitating the offender is not addressed in retribution, deterrence, or incapacitation. But ignoring rehabilitation comes as a cost. In this chapter’s section on jails and prisons, you will read about the challenge of relying heavily on these facilities. About 95 percent of people released from prison had little or no rehabilitative support while incarcerated (Bureau of Justice, 2004). And yet there is the expectation that individuals leaving prisons will not commit crimes in the future.

The question here is this: what have we done to help change them so they are not reoffending? Without the incorporation of some form of rehabilitation, the answer is fairly clear. . . Nothing. Yet, we expect it.

8.2.2.5 Understanding Risk and Needs in Rehabilitation

Today’s rehabilitative efforts still carry punishment and societal protection as goals, but the focus of rehabilitation is on the changing of individuals’ behaviors so that they do not recidivate. To change behavior, corrections professionals need to understand what causes some individuals to be at risk for offending and what causes some individuals to be at higher risk for offending than others. Risk factors include items like prior criminal history, antisocial attitudes, antisocial or procriminal friends, a lack of education, family or marital problems, a lack of job stability, substance abuse, and personality characteristics, like mental health issues and antisocial personality.

While we can’t change the number of prior offenses someone already has, all of these other items can be addressed. These are considered as criminogenic needs. Criminogenic needs are items that, when changed, can lower an individual’s risk of offending. This is a core component of Paul Gendreau’s principles of effective intervention, and are at the heart of most modern effective rehabilitation programs (1996). Thousands of individuals have been assessed on these items, which has helped to develop evidence-based rehabilitation practices. When these criminogenic needs are addressed, higher-risk individuals demonstrate positive reductions in their risk to offend.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been noted as one of the most effective approaches to changing criminogenic needs. Cognitive behavioral therapy is based on the concept that behaviors can be changed by changing thinking patterns behind the behaviors, or before the behaviors are exhibited. Criminal behavior is based on cognition, values, and beliefs that are learned through the interactions and observations of others. This is important when rehabilitating individuals from prison, where antisocial ideas, peers, values, and beliefs may dominate the institution.

8.2.2.5.1 Dig Deeper

For a more detailed explanation, please see What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?

Today, evidence-based rehabilitative efforts are now used as benchmarks when establishing programs that are seen as effective. Rehabilitation programs that follow principles of effective intervention show that they can achieve the three goals of corrections, punishment, societal protection, and rehabilitation. In fact, there is a department in the National Institute of Justice devoted to these evidence-based practices that evaluates programs to see which are effective and not effective. We will discuss some specific examples of these programs later in this chapter.

8.2.3 Eras of Corrections

In the U.S. correctional system, history continues to repeat itself through various eras of corrections. From the late 1700s to the present, policymakers, government officials, and the community-at-large have changed how the system impacted those who have committed crimes or been accused of committing them.

Over the years, these eras have attempted to try and “fix” the system and yet what we see is that issues still remain generation after generation. For example, from 1790–1825 corrections focused on locking individuals up and having them repent before God. When the system moved to a focus on mass incarceration. Later the focus moved to reforming individuals and providing education and work training. When that became expensive, the focus shifted to an industrial era in which incarcerated individuals worked and performed labor and tasks to make the facilities more self-sufficient.

In the last 100 years this cycle from punitive punishment to treatment to community-based to warehousing has come and gone around again, depending on the mindsets of the community and policymakers of the moment. In the next chapter you will learn about how some of these changes have impacted communities. Specifically, you’ll learn about how these philosophies of punishment have inequitably impacted communities of color over time, and what that means for the field of criminal justice.

8.2.3.1 Dig Deeper

To learn more about how some of these historical eras have impacted certain groups, review the American History, Race, and Prison | Vera Institute article.

8.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Philosophies of Punishment

“Philosophies of Punishment” by Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “8.1. A Brief History of the Philosophies of Punishment”, “8.2. Retribution”, “8.3. Deterrence”, “8.4. Incapacitation”, and “8.5. Rehabilitation” by David Carter in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 8.1. Hammurabi Code (Figure) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 8.2. The Warrior Prison Ship (Figure) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 8.3. Elmira Reformatory (Figure) is in the Public Domain.