8.4 Prisons

A prison is a place in which individuals convicted of felony crimes are held. The differences between jails and prisons have developed overtime with the growth of both institution types with distinct purposes. As discussed in the previous section, jails are looked at by society as a more temporary holding location, for those pending court appearances or who have been sentenced to “shorter” (less than one year) sentences. Where prisons have developed into institutions used to house convicted felons for more than one year and in some cases for life sentences. We will cover these topics in more detail in this section.

8.4.1 Growth of Prisons in the United States

As mentioned in the previous section, the Walnut Street Jail is recognized as the first built institution in the United States to house individuals, functionally becoming a prison in 1776 (Skidmore, 1948-1949). In 1829, another prison opened in Philadelphia, the Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP), pictured in figure 8.9., and it ran like a prison for nearly 150 years. The word “penitentiary” came from the Pennsylvania Quakers’ belief in penitence and self-examination as a means to salvation (Huang & Lee, 2020). Many of the prisons today were first built on this idea of a separated penitent prison. Many of the cells in the prison would open to individual courtyards where individuals could look up and “get right with God,” hence the concept of penitentiary or penance. Individuals in ESP spent much of their time in their cells, or in their own reflection yards, reading the Bible, praying, and always in silence. Solitude was believed to be a way to serve penance.

Figure 8.9. The State Penitentiary for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, Lithograph by P.S: Duval and Co., 1855.

In 1819 another prison was built in New York named the Auburn Prison. This prison would become the model of the second main prison style, the Auburn prison system. Auburn utilized a congregate system, which meant that the individuals incarcerated there would gather to do tasks or work in silence.

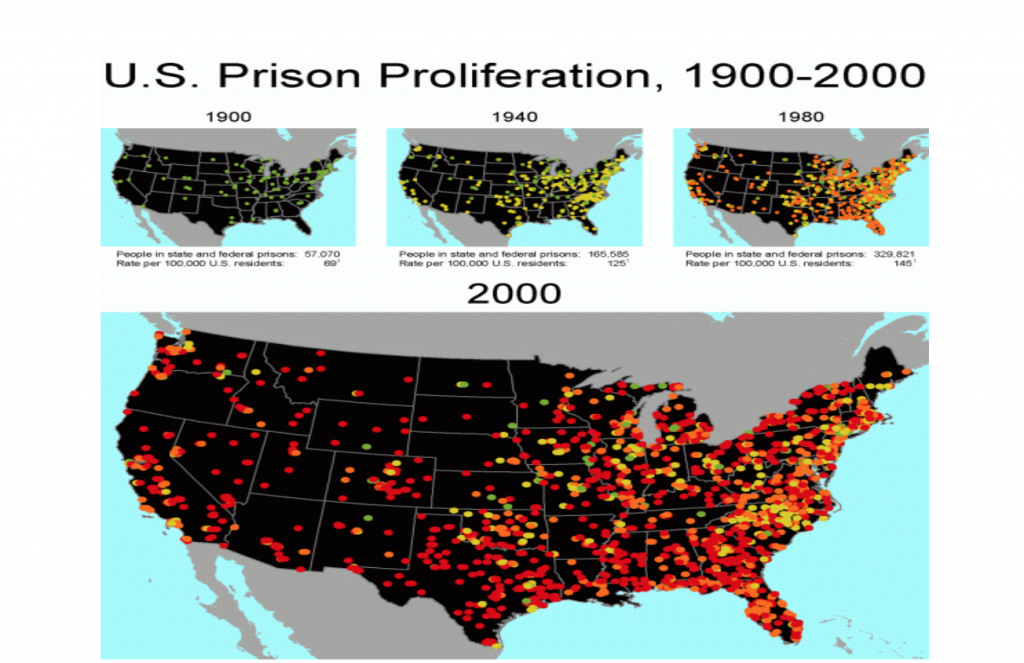

Proliferation, or the concept of labor, eventually replaced the ideals of constant solitude. The congregate system took hold as the dominant model for many prisons, and many states began to model their prisons on the Auburn prison. Notably, Auburn was also the prison where the first death by electric chair was executed in 1890. Today, there are roughly 1,566 State prisons in the United States (Initiative & Wagner, 2022). As figure 8.10. demonstrates, it is clear that many of the prisons in the U.S. have been built more recently.

Figure 8.10. Prison Growth in the U.S.

8.4.2 Prison Jurisdictions

There are two ways to categorize prisons in the United States. The first is by jurisdiction which refers to which organization manages the prisons. A prison warden is considered the managerial face of the institution. However, a prison warden and the prison itself is part of a much larger organizational structure, usually separated by state. Some nonstate jurisdictions manage or operate prisons, including U.S. cities and territories like New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

8.4.2.1 State Prisons

At the state level, most prisons are organized under a Departments of Corrections, which is run by a director, who is usually appointed by a governor. For example, the Oregon Department of Corrections has a governor-appointed director. The Oregon Department of Corrections (ODOC) currently oversees twelve State prisons.

8.4.2.2 Federal Facilities

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (FBOP or BOP) was established in 1930 to house an increasing number of individuals convicted of federal crimes. While there were some federal facilities at the time, congressional legislation officially created the BOP as a division of the Justice Department. Sanford Bates became the first Director of the FBOP based on his long-standing work as an organizer and leader at Elmira Reformatory in New York. Today, the BOP has 132 facilities (prisons, camps etc.) across the nation. There are also military prisons, alternative facilities, reentry centers, and training centers that are managed by the BOP. The federal prisons are separated into regions. Within these regions are regional directors, who are similar to state-level directors for departments of corrections.

8.4.2.2.1 Dig Deeper

To see a detailed listing and map facilities run by the Federal Bureau of Prisons visit BOP: Locations By State.

8.4.3 Private Prisons

Often to cut costs the state will allow private companies to provide goods and services within the prison. This privatization is a long-standing practice of states’ department of corrections. This includes services like food and transportation services, medical, dental, and mental health services, education services, even laundry services.

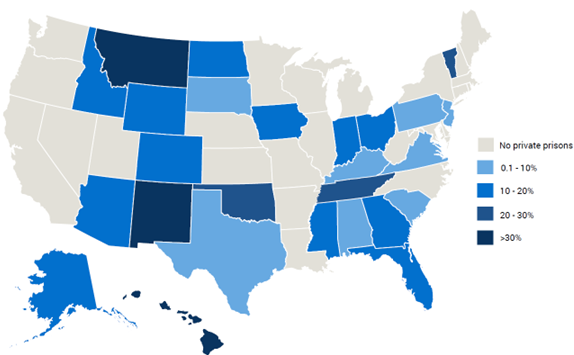

As mentioned in the previous section on punishment, crime became highly politicized in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s which brought about an increased fear of crime and a more punitive state within the U. S. It was during this time that a small company known as Wackenhut, a subsidiary of The Wackenhut Corporation (TWC) sought to privatize the entirety of a prison, not just services within the prison. A second company, Corrections Corporation of America ultimately won the contract and became the first privately owned prison in the United States (in 1984). Today, CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America) runs approximately 113 correctional, detention, or reentry facilities in the United States (CoreCivic, n.d.). The GEO Group, the other primary private prison company, runs 136 correctional, detention, or reentry facilities (StackPath, n.d.). Figure 8.11. shows that in 2020,roughly half of the states had privately run prisons.

Figure 8.11. Percent of Imprisoned People in Private Prisons, 2020 (cropped).

8.4.3.1 States Using Private Prison Industry

Much debate has come from the incorporation of private prisons. The critics of private prisons denote the lack of transparency in the reporting processes that would come from a normal prison. Still, others tackle a bigger issue—punishment for profit. That is—while taxpayers ultimately pay for all punishment of individuals, either at the State or Federal level, shareholders and administrators of the companies are making money by punishing people, under the guise of capitalism.

8.4.3.1.1 Dig Deeper

It’s important to understand the equity issues caused by the privatization of prisons. To understand the larger scope of these issues watch the following video on prison privatization and read the article on Private Prisons in the United States presented by the Sentencing Project.Adam Ruins Everything – The Shocking Way Private Prisons Make Money

8.4.4 Prison Levels

Each prison jurisdiction also operates facilities of varying degrees of intensity or seriousness. These are often considered prison levels or classifications. Prison level is associated with the seriousness of crimes committed by the individuals housed within these institutions. For example, many states have three classification levels: minimum, medium, and maximum. Some states have a fourth level called super-maximum, close, or administrative level. The BOP has five levels: minimum, low, medium, high, and unclassified. ADX Florence is a United States Penitentiary (USP) that would be considered an unclassified facility known as a super-max. It houses the most dangerous individuals at the Federal level. Although not in operation today, Alcatraz, seen in figure 8.12., was probably the most famous Federal USP and was also considered a super-max at one point. It too housed the most dangerous federal custodies.

Figure 8.12. The iconic Alcatraz prison, known as the “rock.”

Some states use a simple number designator to assign prison intensity, such as Level I, Level II, Level III, Level IV, and sometimes Level V. Others incorporate a Camp level to their list of designations. The facilities have a specific purpose within the low level, such as a Fire Camp, which is dedicated to fighting fires.

8.4.4.1 Intake Centers

An intake center can be part of an institution, running alongside the normal operations of an institution, or standing-alone as a separate institution. The purpose of an intake center is to classify felony-convicted individuals coming from courts in the jurisdiction. The individual’s initial classification comes from a points-based assessment and determines which of the jurisdiction’s prisons they are assigned to. This assessment is looking at prior convictions, prior and current violence, escape risk, potential self-harm, and more. For example, Coffee Creek Correctional Facility (CCCF) in Oregon is the intake facility for the Oregon Department of Corrections (DOC). It also is the women’s prison in Oregon. All individuals in the DOC jurisdiction come to CCCF and are assessed. If male, they are then transported to one of the other institutions in Oregon. If female, they are placed in a level within CCCF. Individuals will gain later classifications at their destination prison, in terms of work assignments, programming, mental health status, cell assignments, and more.

8.4.4.2 Minimum

Minimum prisons usually have dorm-style housing and are typically for only nonviolent individuals with shorter sentences. There is freedom of movement as individuals housed within the prisons have the ability to move about without being escorted from place to place. The fencing or perimeters of these types of facilities are usually low levels. The BOP generally refers to these as camps.

8.4.4.3 Medium

Medium prisons have cells rather than dorms. There are usually two people in a cell. The perimeter is usually a high fence, and may even have barbed wire, or there are large walls surrounding the institution. Freedom of movement within the institution is reduced and seen as a privilege. Individuals housed here typically have longer sentences and have more serious convictions.

8.4.4.4 Maximum

People housed in maximum prisons have been convicted of serious and sometimes violent offenses and have longer sentences, including life in prison. Most cells are single occupancy and many individuals housed here will spend most of their day in a cell. Freedom of movement is even more reduced and seen as a privilege. Perimeter fences are doubled with the use of wire and cement block fences circling the prison. Exterior fences often have towers with armed-guards manning them.

8.4.4.5 Administrative

Administrative prisons have different missions and the individuals housed in these institutions could be vastly different. For instance, a prison designated to address mental health concerns does not operate the same way as a super-max. The supermax houses individuals in their cells for almost the entire day, every day. The cells are almost all single occupancy. Many services, like sick calls and meals, come to individuals in their cell, instead of them going to a cafeteria or infirmary. Most of these individuals are also classified as extreme threats and have long sentences like life without the possibility of parole.

8.4.5 Who Goes to Prison?

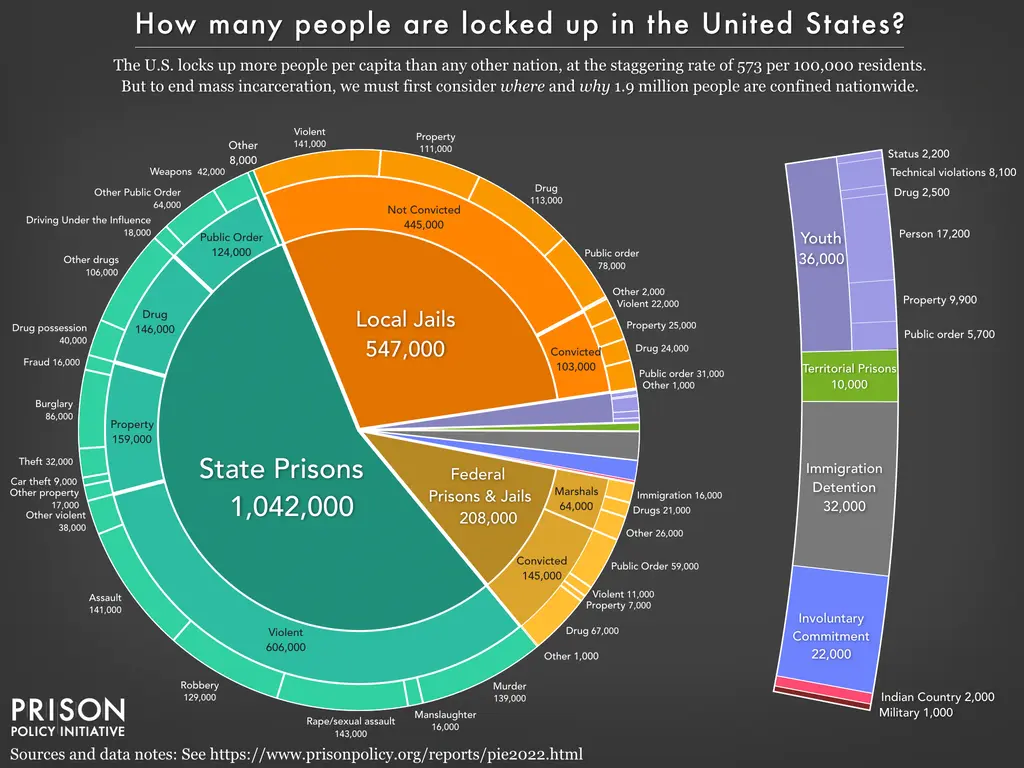

All people who go to prisons in the United States are people who have been convicted of felony-level crimes and are serving more than a year for their conviction. Figure 8.13 shows a more detailed depiction of the crimes and population breakdown in prisons.

Figure 8.13. Number of individuals incarcerated in correctional facilities in the United States.

Focusing in on the left side of the graphic, there are roughly 1,042,000 locked up in State prisons. Here we can see the types of crimes that they are convicted of. A little over half (58 percent) are incarcerated for violent crimes. Drug crimes and property crimes make up the next big sections. When you add in those in federal facilities (about 208,000), territorial prisons (10,000), Indian Country prisons (2,000) and military prisons (1,000), we start to see how that number changes to about 1,263,000 not including privatized prison populations.

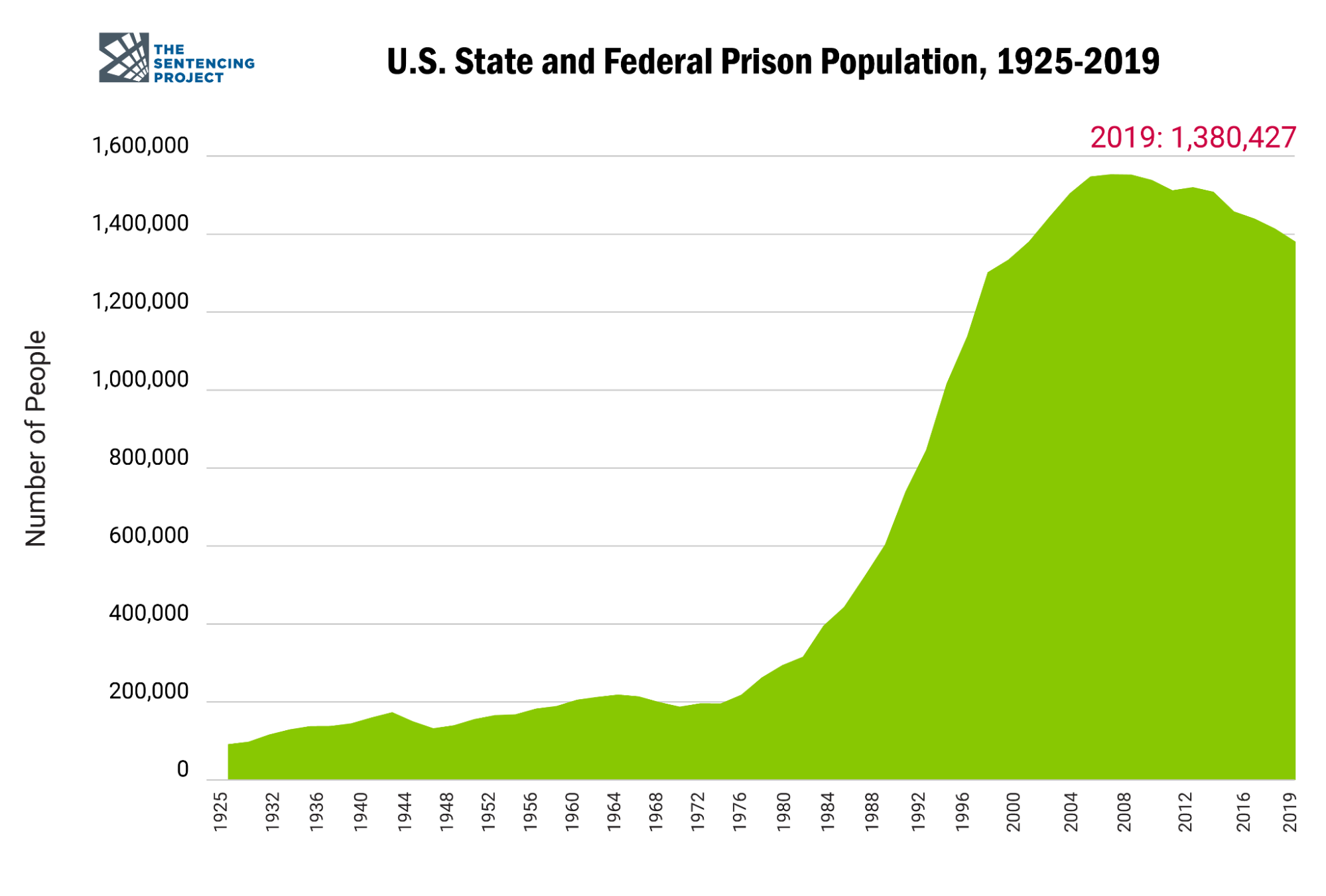

While the total volume of those in prison has dropped slightly in the last few years (since 2015), Figure 8.14. shows the overall numbers have increased substantially over the last 45 years.

Figure 8.14. Graph showing prison population growth from 1925–2019.

Figure 8.14. Graph showing prison population growth from 1925–2019.

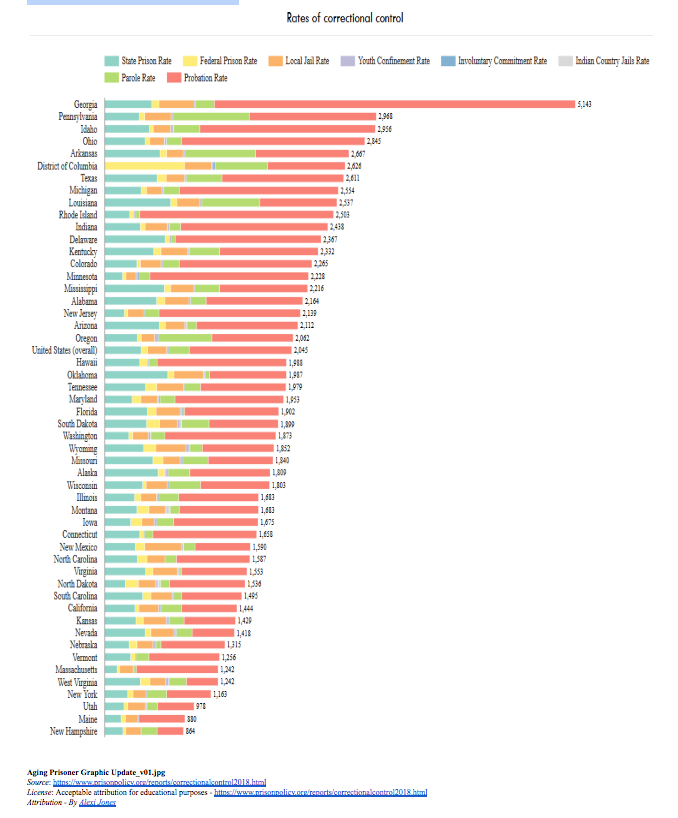

It is estimated that we have over 8 million people in correctional control, and that number does not seem to be subsiding. Yes, there are reductions in certain areas, such as a decline in the prison population in the last few years, but this does not mean that they are not still under control. In one of the more detailed examples of just where individuals are at in corrections, Alexi Jones (2018) of the Prison Policy Initiative provides a graphic, figure 8.15., based on State and Federal data to demonstrate this impact.

Figure 8.15. Rates of Correctional Control Breakdown by individual states.

Not only does this graphic demonstrate the overall volume of correctional control, but it also highlights how states are handling their populations differentially. The second half of Jones’ report details the volume of individuals within each state (2018). Please take a moment to review the last portion of this report to see how many are under correctional control, found here: Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and supervision by state | Prison Policy Initiative.

Prison overcrowding is problematic for multiple reasons. First, when there are too many individuals (especially antisocial ones) within a facility, there are more assaults and injuries that occur within the institution. Moreover, there is a safety concern for not only the offender on offender violence but also the offender of staff crimes. Second, the more people you have in a facility, the faster that facility wears down. Operating a jail or prison at maximum (or over maximum) capacity causes more items to break or wear out within the facility at a fast rate.

Finally, when individuals are unable to access adequate health and mental health care because of excessively long waits, due to overcrowding, it is a violation of their constitutional rights.

The public and the State have a responsibility to house and properly care for the individuals who are incarcerated. This is not to say these individuals are getting better care than the community, but that they are at least receiving a modicum of care. When this low level of care is deliberately denied due to excessive volumes of individuals, it is a violation of a person’s 8th amendment rights against cruel and unusual punishment. As was found in the case of Estelle v. Gamble, (1976).

This similar issue was presented in California over ten years ago. A three-judge panel ruled with the incarcerated individuals, citing the need for California to reduce its prison population to a level where the individuals could effectively be managed and cared for [emphasis on the latter]. Dealing with overcrowding is a constant issue for most prisons and jails. Some have resolved to release more out into the community at a higher volume, on parole, or just release. However, this has its own set of problems, as reentry is now becoming the current issue within corrections.

8.4.6 Life and Culture in Prison

Life inside prison walls or fences is structured and organized. A daily routine includes three meals in a cafeteria or served in cells, depending on the individual’s classification level, and completing unit activities of cleaning. Individuals housed in prisons are allotted recreation time, but eligible individuals also have more opportunities than those in jail to participate in programming, treatment, higher-education, and employment opportunities. Visiting is expanded within prisons and many facilities allow eligible individuals contact visits where family and friends are able to see their loved ones without a glass barrier between them.

8.4.6.1 Rights and Privileges

Like people housed in jails, individuals in prison maintain their basic constitutional rights, including to be free from discrimination, to access the courts and counsel, of speech, of religious freedom when it doesn’t impede safety and security, to due process, and to be protected from cruel and unusual punishment. They are also entitled to protections under the Americans with Disabilities Act and, in some cases, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. People in prisons are actually afforded more privileges once housed in prisons.

They have privileges like the ability to purchase additional food, clothing, and toiletry items, but they also have access to more commissary items compared to those housed in jail. Like jails, these privileges are still earned, continuing to incentivize positive behavior.

8.4.6.2 Program and Work Opportunities

Most prisons provide the same basic education and treatment programs as found in jails, like GED, AA, and NA, but some provide additional programs and educational opportunities, like parenting classes, behavior change and support groups, college and university courses, clubs and social activities, and various religious programs.

Additional work opportunities within the facility are encouraged, including basic facility maintenance like plumbing, electrical, and manufacturing. There are also professional organizations and businesses that partner with prisons to provide opportunities to incarcerated individuals for real-world experience. For example, the Oregon Department of Motor Vehicles hires incarcerated individuals to work at call centers located in Oregon Department of Corrections’ prisons. In 1994, Oregon passed a law requiring those incarcerated in prison to work 40 hours a week. Up to 20 of those hours can be fulfilled by participating in job training and educational programs. Currently, in Oregon those participating in the correctional enterprises program receive wages or a stipend, although they are not comparable to those doing similar work in the community.

8.4.7 Licenses and Attributions for Prisons

“Prisons” by Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “8.11 Types of Prisons”, “8.12. Prison Levels”, and “8.13. Who Goes to Prison?” by David Carter in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 8.9. Eastern State Penitentiary aerial is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Figure 8.10. U.S. Prison Proliferation, 1900–2000 © The Prison Policy Initiative. All Rights Reserved, Used with permission materials.

Figure 8.11. “Percent of Imprisoned People in Private Prisons, 2020” (cropped) in Private Prisons in the United States (p. 2) by The Sentencing Project is included under fair use.

Figure 8.12. Alcatraz Image by Nikolay Tchaouchev is licensed under Unsplash

Figure 8.13. How many people are locked up in the United States © The Prison Policy Initiative. All Rights Reserved, Used with permission materials.

Figure 8.14. U.S. State and Federal Prison Population © The Sentencing Project. Used under fair use.

Figure 8.15. Rates of Correctional Control © The Prison Policy Initiative. All Rights Reserved, Used with permission materials.