4.4 Forest Setting

Larger trees growing in a forest present the greatest challenge when trying to determine age. As noted before, it is very difficult to estimate tree age simply from size. So much depends on a tree’s microenvironment (access to light, water, space and nutrients), its unique species-dependent growth habits, and the events that alter the tree’s environment or health over the course of its life. The frequency and intensity of disturbances such as fire, insect attacks, or windstorms profoundly influence tree growth over time.

Trees growing in managed forests, particularly evenaged second-growth or third-growth forests, were likely planted. Foresters record the year of planting and seedling age at time of planting. Most companies will have year of establishment printed on company forest maps or indicated on company aerial photos for ease of use. In these cases, simply researching office records before one goes out to the field will provide stand age.

Trees growing in naturally regenerated stands, unmanaged stands, or stands managed for unevenaged structure are harder to evaluate. In these cases, individual tree age can vary greatly from tree to tree. Knowledge of tree silvics can help with ballpark estimates. For example, a young (< 30 yrs.) true fir will have smooth bark with resin blisters. The bark gradually develops plates or fissures as the tree ages. A tree more than 100 years old will have regular, geometric bark patterns. In addition, the crown of a very old tree will have a rounded top, different than the tiered leader of a young tree. On Douglas-fir, the smooth bark gives way to thick fissures in the bark. But these types of physical characteristics, without some site history clues, may only get a person to within about 30 years of the actual age.

Annual Ring Counts

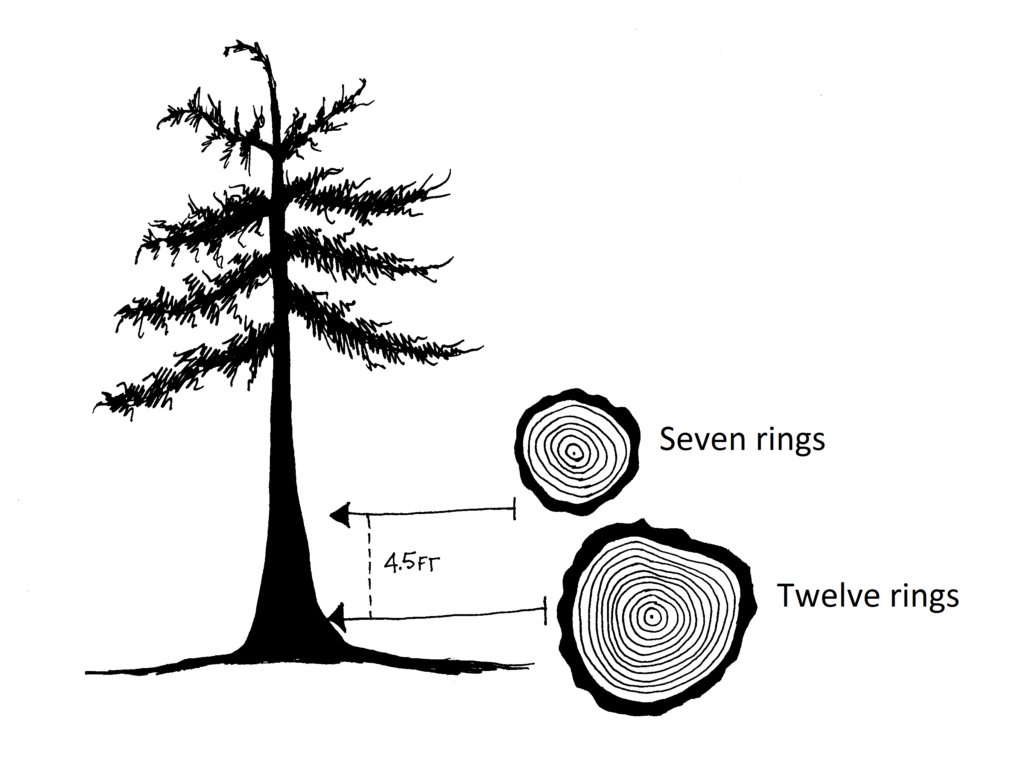

The most direct way of determining tree age is to count a tree’s annual rings. In the Pacific Northwest, trees produce one ring of diameter growth each year, so the number of rings present on a cross-section of the tree’s trunk represents the tree’s age at that height. Counting rings on a stump will result in a pretty accurate estimate of the tree’s age. Counting rings from a cookie cut at a height of 10 feet or 20 feet will tell you how many years the tree grew after it reached that particular height (Figure 4.5). In fact, researchers examine cookies cut from regular intervals along fallen trees to derive information about species’ growth rates, and sometimes to investigate evidence of historical events such as fires, droughts, and insect outbreaks in a science called dendrochronology.