1.12. Street Crime, Corporate Crime, and White-Collar Crime

Shanell Sanchez

As previously demonstrated, crime can be broadly defined, but the two most common types of crime discussed are, street crime and corporate or white-collar crime. Most people are familiar with street crime since it is the most commonly discussed among politicians, media outlets, and members of society. Every year the Justice Department puts out an annual report titled “Crime in the United States” which means street crime but has yet to publish an annual Corporate Crime in the United States report. Most Americans will find little to nothing on price-fixing, corporate fraud, pollution, or public corruption.

Street Crime

Street crime is often broken up into different types and can include acts that occur in both public and private spaces, as well as interpersonal violence and property crime. According to the Bureau of Justice (BJS), street crime can include violent crimes such as homicide, rape, assault, robbery, and arson. Street crime also includes property crimes such as larceny, arson, breaking, burglary, and motor vehicle theft. The BJS also collects data on drug crime, hate crimes, and human trafficking, which often fall under the larger umbrella of street crime.[1]

Fear of street crime is real in American society; however, street crime may not be as rampant as many think. In a 2017 report, the BJS found that the rate of robbery victimization increased from 1.7 per 1,000 persons in 2016 to 2.3 in 2017. Overall, robbery happens to a small percentage of Americans, which also seems to be a similar trend when looking at the portion of persons aged 12 or older who were victims of violent crime. The BJS noted an increase from 0.98% in 2015 to 1.14% in 2017, but note the small percentage overall. Further from 2015 to 2017, the percentage of persons who were victims of violent crime increased among males, whites, those ages 25 to 34, those aged 50 and over, and those who had never married. There are clear risk factors that can be taken into account when attempting to develop policy, which is discussed in subsequent chapters of the book. There were also areas where the BJS noted a downward trend in crime, such as the decline in the rate of overall property crime from 118.6 victimizations per 1,000 households to 108.4, while the burglary rate fell from 23.7 to 20.6. [2]

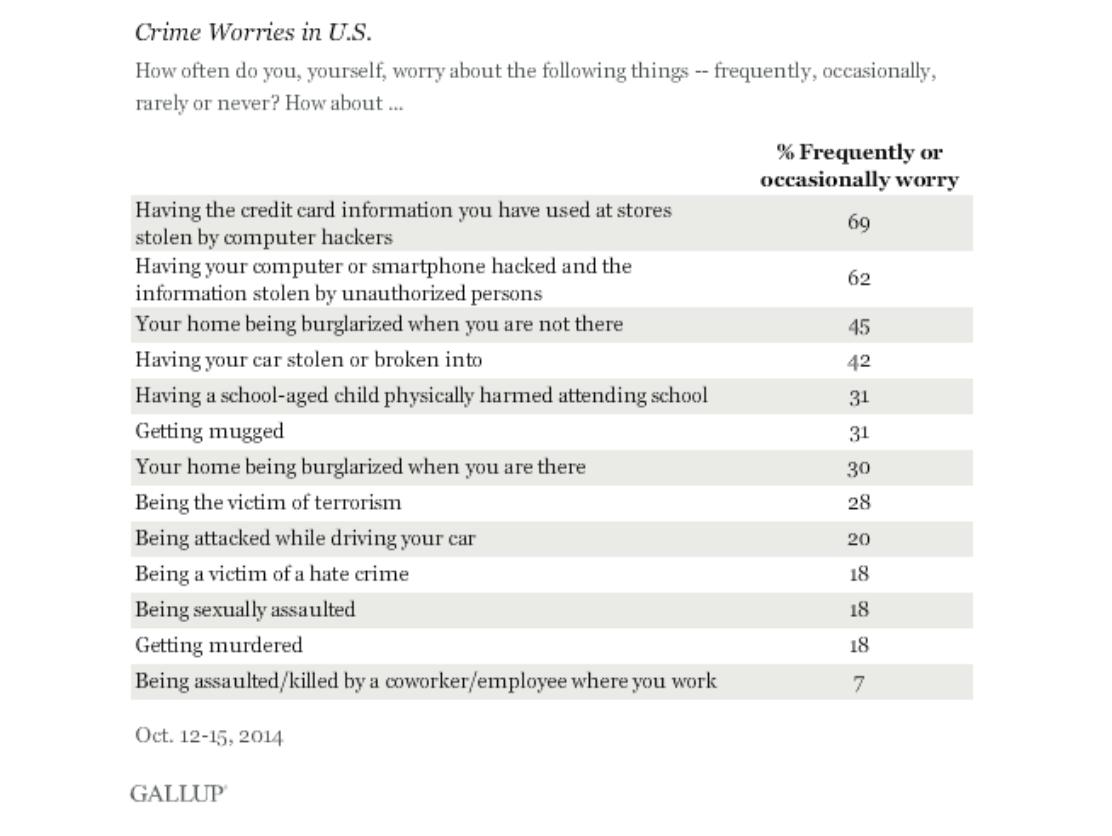

Polls have consistently found that people are worried about crime in the United States, specifically street crime. Riffkin (2014) found that people worry about various crimes such as homes getting burglarized when they were home, the victim of terrorism, being attacked while driving their car, being murdered, the victim of a hate crime, and being sexually assaulted https://news.gallup.com/poll/178856/hacking-tops-list-crimes-americans-worry.aspx. Most people in society, people can go about their daily lives without the fear of being a victim of street crime. Street crime is important to take seriously, but it is reassuring to note that it is unlikely to happen to most people. The conversation should happen around why fears are high, especially amongst those less likely to be a victims. For example, elderly citizens have the greatest fear of street crime, yet they are the group least likely to experience it. Whereas younger people, especially young men, are less likely to fear crime and are the most likely to experience it. [3]

Because Americans are often fearful of street crime, for various reasons, resources are devoted to prevention and protecting the public. The United States spends roughly 265.2 billion dollars a year and employs more than one million police officers, almost 750,000 correctional officers, and more than 490,000 judicial and legal personnel on street crime. [4] The Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) estimated 2015 financial losses from property crime at $14.3 billion in 2014 (FBI, 2015a), but keep that number in mind for a minute. [5] Although it is crucial to recognize that street crime does occur, and it impacts certain groups disproportionately more than others, it is also important to recognize other types of crimes commonly talked discussed. The BJS does not have a link that directs people to the next two types of crime discussed when on their main page of crime types.

Corporate Crime

When most people think of crime, they think of acts of interpersonal violence or property crime. The typical image of a criminal is not someone who is considered a ‘pillar’ in society, especially one who may have an excellent career, donate to charity, devote time to the community, and engage in ‘normal’ behavior. [6] Corporate crime is an offense committed by a corporation’s officers who pursue illegal activity (various kinds) in the name of the corporation. The goal is to make money for the business and run a profitable business, and the representatives of the business. Corporate crime may also include environmental crime if a corporation damages the environment to earn a profit. [7] As C. Wright Mills (1952) once stated, “corporate crime creates higher immorality” in U.S. society. [8] Corporate crime inflicts far more damage on society than all street crime combined, by death, injury, or dollars lost.

Credit Suisse pled guilty to helping thousands of Americans file false income tax returns, and the company got fined $2.6 billion. Last year, BNP Paribas pled guilty to violating trade sanctions and was forced to pay $8.9 billion, which exceeds the yearly pocket costs of all the burglaries and robberies in the United States ($4.5 billion in 2014 according to the FBI). Another example is healthcare fraud. The estimates suggest this costs Americans $100 billion to $400 billion a year. [9]

In 2001, the energy company Enron committed accounting and corporate fraud, where shareholders lost $74 billion in the four years leading to its bankruptcy, thousands of employees lost jobs, and billions of dollars got lost in pension plans. [10]

In addition to financial loss, corporate crime can be violent. In 2016, the FBI estimated the number of murders in the nation to be 17,250. [11] Compare 54,000 Americans who die every year on the job or from occupational diseases such as black lung and asbestosis and the additional tens of thousands of other Americans who fall victim every year to the silent violence of pollution, contaminated foods, hazardous consumer products, and hospital malpractice. [12] A vast majority of these deaths are often the result of criminal recklessness. Americans are rarely made aware of them, and they rarely make their way through the criminal justice system.

The last major homicide prosecution brought against a major American corporation was in 1980. A Republican Indiana prosecutor charged Ford Motor Co. with homicide for the deaths of three teenage girls who died when their Ford Pinto caught on fire after being rear-ended in northern Indiana. The prosecutor alleged that Ford knew that it was marketing a defective product, with a gas tank that was crushed when rear-ended, spilling fuel, where the girls incinerated to death. Ford hired a criminal defense lawyer who in turn hired the best friend of the judge as local counsel, and who, as a result, secured a not-guilty verdict after persuading the judge to keep key evidence out of the jury room. [13] https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fatal-ford-pinto-crash-in-indiana.

Sometimes the terms corporate and white-collar crime are used interchangeably, but there are important distinctions between the two terms. [14]

White-Collar Crime

In contrast to corporate crime, white-collar crime usually involves employees harming the individual corporation. Sometimes corporate and white-collar crime go hand in hand, but not always. An example of white-collar crime would be the financial offenses of Bernard Madoff, who defrauded his investors of approximately $20 billion. Instead of trading stocks with his client’s money, Madoff had for years been operating an enormous Ponzi scheme, paying off old investors with money he got from new ones.

By late 2008, with the economy in free fall, Madoff could no longer attract new money, and the scheme collapsed, which resulted in hundreds of investors, including numerous charities, being wiped out. As of today, a court-appointed trustee has managed to recover about $13 billion, which is most of the money Madoff’s investors put into his funds. The trustee sold off the Madoff family’s assets, including their homes in the Hamptons, Manhattan, and France and a 55-foot yacht named Bull. [15]

Dr. Sanchez’s Professor in Graduate School

In 2008, many people were negatively impacted by Madoff, one of which was a former professor of Dr. Sanchez. He lost his retirement, which required him to keep teaching well into his 80s, as well as lost his home. The impact of Madoff was far-reaching and although most may call it a purely economic crime, people committed suicide and lost everything in this scandal.

No official program measures corporate and white-collar crime like there is with street crime occurring in the United States. Therefore, we estimate costs to society, and who the victims are. Additionally, unlike street crime where the crime can often be discovered instantly and investigated quickly, corporate and white-collar crime can take years to investigate and even longer to prosecute. Remember, Madoff was involved in fraud most of his working life but was not caught until he was nearing the end at the age of 71. [16]

- https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=316 ↵

- Morgan, R., & Truman, J., (December 2018). NCJ 252472 ↵

- Doerner, W. G., & Lab, S.P. (2008). Victimology (5th ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: Lexis-Nexis. ↵

- Kyckelhahn, T. (2012). Justice expenditure and employment extracts. Bureau of Justice Statistics ↵

- FBI. (2015b), September 28). The latest crime stats were released. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice. ↵

- Fuller, J.R. (2019). Introduction to criminal justice. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Fuller, J.R. (2019). Introduction to criminal justice. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Horowitz, I. (Ed.) (2008), Power, politics, and people. Wright Mills, C. (1952). A diagnosis of moral uneasiness (pp.330-339). New York: Ballantine. ↵

- (2000). License To Steal: How Fraud Bleeds America's Health Care System. Westview Press. ↵

- Folger, J. (November 2011). The Enron collapse: A look back. Investopedia. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/updates/enron-scandal-summary/ ↵

- FBI: UCR. 2016. FBI Murder. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/topic-pages/murder ↵

- Mokhiber, R. Corporate crime & violence: Big business power and the abuse of the public trust. Random House, Inc. ↵

- Steinzor, R. (Dec. 2014). It’s called 'Why Not Jail?': Industrial catastrophes, corporate malfeasance, and government inaction. Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Kleck, G. (1982). On the use of self-report data to determine the class distribution of criminal and delinquent behavior." American Sociological Review, 427-433. ↵

- Zarroli, J. (2018). For Madoff victims, scars remain 10 years later, National Public Radio, https://www.npr.org/2018/12/23/678238031/for-madoff-victims-scars-remain-10-years-later ↵

- Fuller, J.R. (2019). Introduction to Criminal Justice. New York: Oxford, Oxford University Press. ↵