5.4 Neoclassical

Classical ideology was the dominant paradigm for over a century. But it was eventually replaced by positivist approaches that seek to identify causes of criminal behavior, which you will learn about in the next section. However, classical ideology had a resurgence during the 1970s in the United States that is called neoclassical theory. Neoclassical theory recognizes people experience punishments differently and that a person’s environment, psychology, and other conditions can contribute to crime as well. In neoclassical theory, crime is a choice based on context. Many crime-prevention efforts used classical and neoclassical premises to focus on “what works” in preventing crime instead of focusing on why people commit criminal acts.

5.4.1 Activity: In the News: Oregon Measure 11 Example

In 1994, Oregon voters passed Measure 11, which established mandatory minimum sentencing for several serious crimes. Besides removing the judge’s ability to give a lesser sentence, Measure 11 prohibited prisoners from reducing their sentence through good behavior. Additionally, any defendant 15 years old or older who was accused of a Measure 11 offense was automatically tried as an adult. Recently, the Oregon Justice Resource Center reported the effects of Measure 11 on juveniles, especially minorities and many groups are actively working to reform Measure 11. Below are links to the news article and the report itself.

- The Oregonian – “New Report Calls Measure 11 Sentences for Juveniles ‘Harsh and Costly’”.

- Oregon Justice Resource Center’s Report Youth and Measure 11 in Oregon: Impacts of Mandatory Minimums.

Activity: Measure 11 Exercise

After reading the above box and hyperlinks, please explain why many juveniles are not deterred from committing serious crimes in Oregon.

5.4.2 Rational Choice Theory

Derek Cornish and Ronald Clarke (1986) proposed Rational Choice Theory to explain criminals’ behavior. They claimed offenders rationally calculate costs and benefits before committing crime and assume people want to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. The theory does not explain motivation, but instead it expects some people will always commit a crime when given the opportunity. They do not assume offenders are entirely rational, but they do have bounded rationality, which means that offenders must make a decision in a timely fashion with the information at hand before committing a crime. For example, if you were walking down a street and noticed an open window in a parked car, you may contemplate looking in. If you saw something inside, you may then consider stealing it. An entirely rational person may look around to see if there are any witnesses, try to determine if the owner is coming back soon, and so on. You may wait until nightfall. However, you may miss your opportunity. Thus, you need to make a quick decision with the relevant facts at that time.

That was an example of a “crime-specific” model, which is a model where all crimes have different techniques and opportunities. This model assumes that all crime is purposeful with the intention to benefit the offender. To dissuade offenders, Rational Choice Theory emphasized the significance of informal sanctions and moral costs. The theory advocates for a situational crime prevention approach by reducing opportunities. Reducing opportunities is much easier to manipulate and change compared to changing society, culture, or individuals. Ultimately, situational crime prevention strategies try to make crime a less attractive choice.

5.4.3 Routine Activity Theory

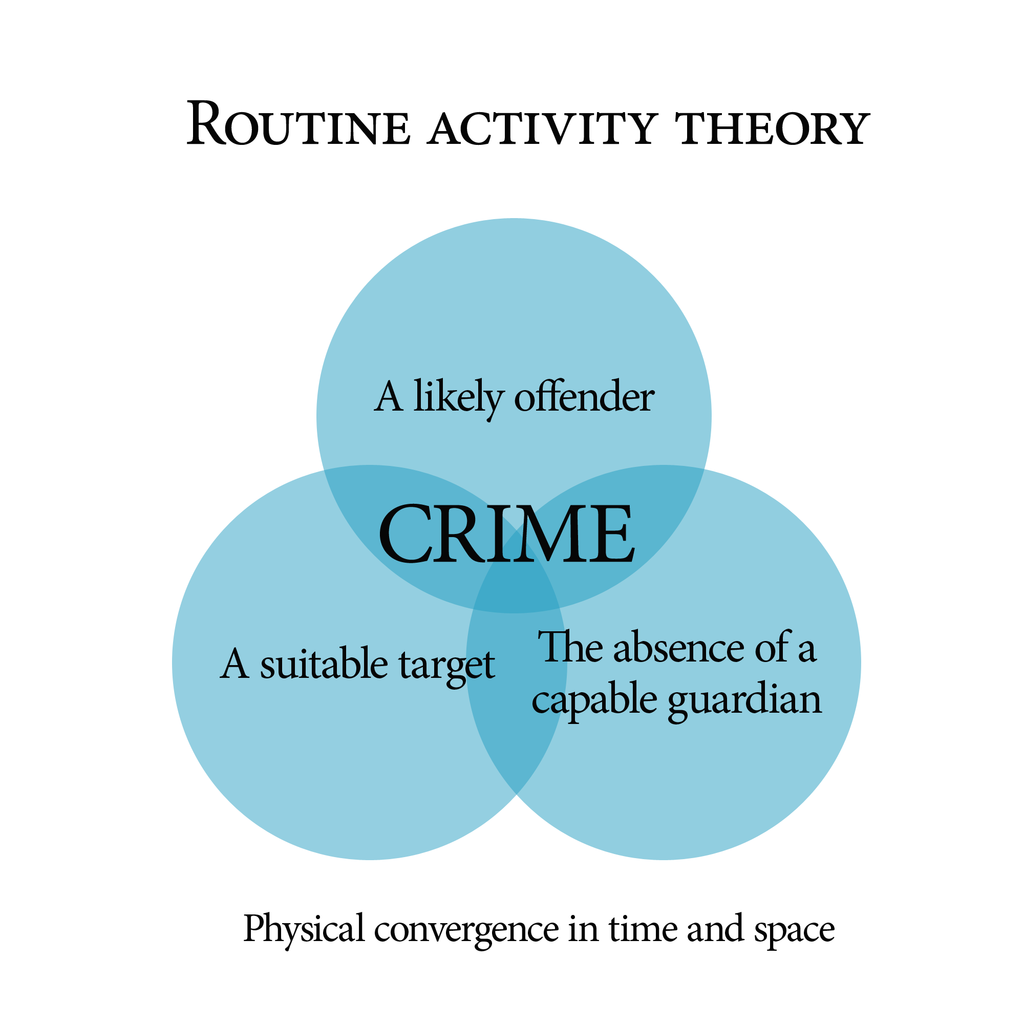

Another neoclassical theory is Routine Activity Theory, which was developed by Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson in 1979. It claims that changes in the modern world have provided more opportunities for offenders to commit crime. Routine Activity Theory says that three things must converge in time and space for a crime to be committed. They include a motivated offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian.

Figure 5.3. A diagram showing Routine Activity Theory in which the convergence of each of the three concepts: a likely (motivated) offender, a suitable target, and the absence of a capable guardian, within the same time and space creates an opportunity for a crime to be committed.

The motivated offender is considered to be a given as there will always be people who will seize opportunities to commit criminal offenses. Besides, there are a variety of theories to explain why people commit a crime. Suitable targets can be vacant houses, parked cars, a person, or any item. In reality, almost anything can be a suitable target. Finally, the absence of a capable guardian facilitates the criminal event. What can serve as a capable guardian? A plethora of people and things can serve as a guardian. For example, police officers, security guards, a dog, being at home, or even increased lighting to allow other people to see. Other examples are: security cameras, alarm systems, and deadbolt locks which can each reduce opportunities by serving as a capable guardian. Routine Activity Theory concentrates on the criminal event instead of the criminal offender.

5.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for Neoclassical

Figure 5.3. Routine Activity Theory is licensed under the CC BY SA-3.0.

“Neoclassical” by Sam Arungwa, Megan Gonzalez, and Trudi Radtke is adapted from “5.5. Neoclassical” by Brian Fedorek in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity.