5.3 Organic Sedimentary Rocks

Organic sedimentary rocks are those containing large quantities of organic molecules. Organic molecules contain carbon, but in this context we are referring specifically to molecules with carbon-hydrogen bonds, such as materials from the soft tissues of plants and animals. In other words, the carbon in calcite- CaCO3 wouldn’t make calcite an organic mineral because it isn’t bonded to hydrogen.

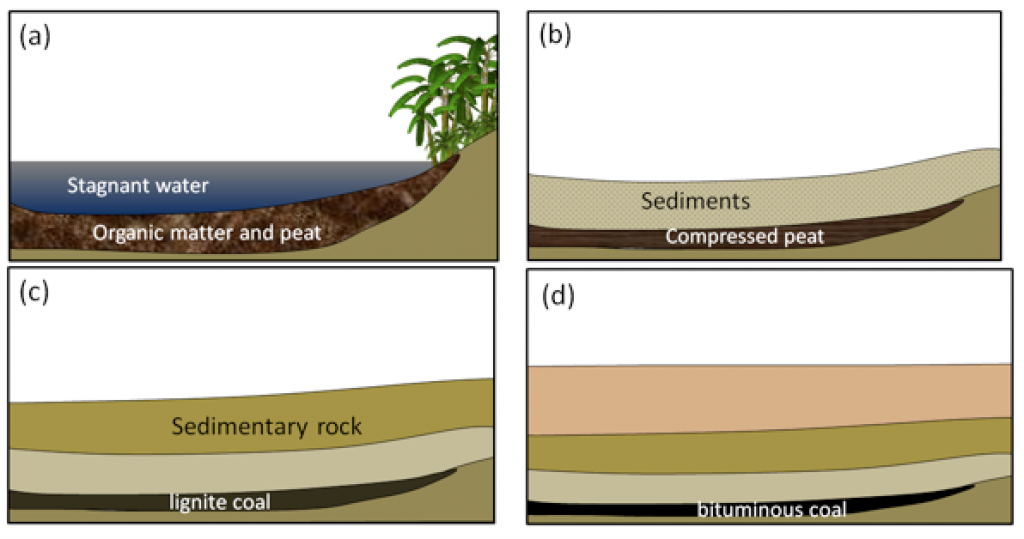

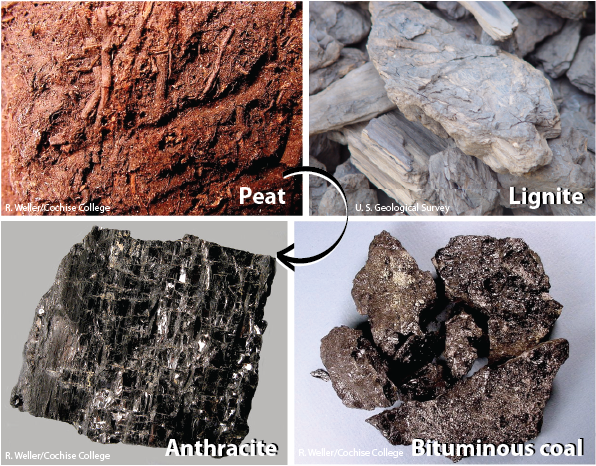

An important organic sedimentary rock is coal. Most coal forms in swampy land adjacent to rivers and within deltas, and where climates are humid and tropical to temperate. The vigorous growth of vegetation leads to an abundance of organic matter that accumulates within stagnant, acidic water. This limits decay and oxidation of the organic material. If this situation—where the dead organic matter is submerged in oxygen-poor water—is maintained for centuries to millennia, a thick layer of material can accumulate. Limited decay will transform this layer into peat (Figure 5.18a, Figure 5.19 upper left).

At some point the swamp deposit is covered with more sediment — typically because a river changes its course or sea level rises (Figure 9.18b). As more sediments are added, the organic matter is compressed and heated as temperatures increase with depth. This has the effect of concentrating the carbon within the coal. The amount of heating will determine how far this process progresses.

The further the process does progress, the more the coal will go from having obvious pieces of plant material within it, to being a black, shiny mass. Low-grade lignite coal forms at depths between 100 m to 1,500 m and temperatures up to ~50°C (Figure 5.18c). This is still a relatively early stage in the coal formation process, so the lignite commonly displays plant fossils that have not yet been destroyed in the process of coalification (Figure 5.19 upper right).

At between 1,000 m to 5,000 m depth and temperatures up to 150°C m, bituminous coal forms (Figure 5.18d, 5.19 lower right). At depths beyond 5,000 m and temperatures over 150°C, anthracite coal forms (Figure 5.19 lower left). In fact, as temperatures rise, the lower-grade forms of coal are actually being transformed from sedimentary to metamorphic rocks.

The transition from peat to anthracite results in a progressive increase in the carbon concentration, in hardness, and in the amount of energy available to be released upon combustion.

Licenses and Attributions

“Physical Geology, First University of Saskatchewan Edition” by Karla Panchuk is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Adaptation: Renumbering