7.1 Alfred Wegener’s Arguments for Plate Tectonics

Alfred Wegener (1880-1930; Figure 7.2) earned a PhD in astronomy at the University of Berlin in 1904, but had a keen interest in geophysics and meteorology, and focused on meteorology for much of his academic career.

![Alfred Wegener during a 1912-1913 expedition to Greenland. [Source: Alfred Wegener Institute (Public domain)]](https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/240/2021/07/Wegener_Expedition-1930_008-scaled.jpg)

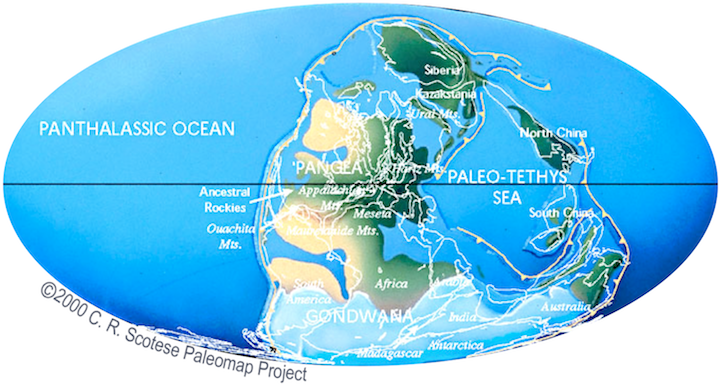

In 1911 Wegener happened upon a scientific publication that described matching Permian-aged terrestrial fossils in various parts of South America, Africa, India, Antarctica, and Australia. He concluded that because these organisms could not have crossed the oceans to get from one continent to the next, the continents must have been joined in the past, permitting the animals to move from one to the other (Figure 7.3). Wegener envisioned a supercontinent made up of all the present day continents, and named it Pangea (meaning “all land”). He described the motion of the continents re-configuring themselves as continental drift.

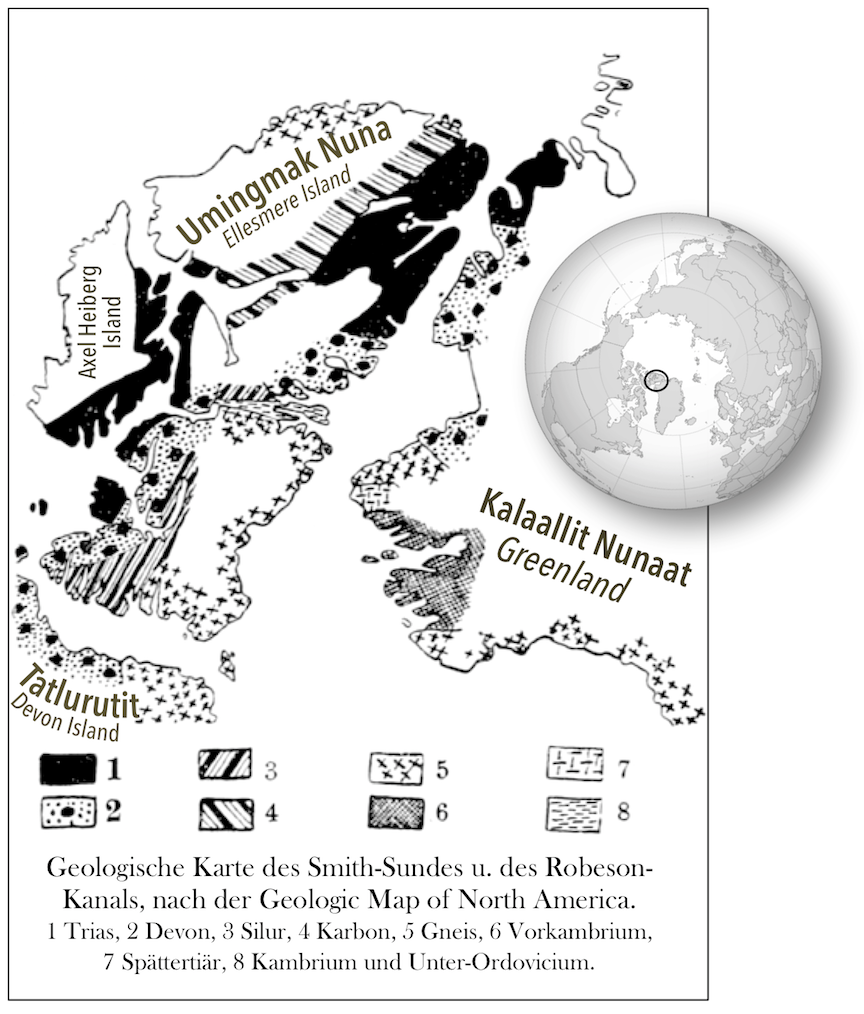

Wegener pursued his idea with determination, combing libraries, consulting with colleagues, and making observations in an effort to find evidence in support of it. He relied heavily on matching geological patterns across oceans, such as sedimentary strata in South America matching those in Africa, North American coalfields matching those in Europe, the mountains of Atlantic Canada matching those of northern Britain—both in structure and rock type—and comparisons of rocks in the Canadian Arctic with those of Greenland (Figure 7.4).

Wegener also called upon evidence for the Carboniferous and Permian (~300 Ma) Karoo Glaciation from South America, Africa, India, Antarctica, and Australia (Figure 7.5). He argued that this could only have happened if these continents were once all connected as a single supercontinent. He also cited evidence (based on his own astronomical observations) that showed that the continents were moving with respect to each other, and determined a separation rate between Greenland and Scandinavia of 11 m per year, although he admitted that the measurements were not accurate. (The separation rate is actually about 2.5 cm per year.)

Wegener first published his ideas in 1912 in a short book called Die Entstehung der Kontinente (The Origin of Continents), and then in 1915 in Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane (The Origin of Continents and Oceans). He revised this book several times up to 1929. It was translated into French, English, Spanish, and Russian in 1924.

The main criticism of Wegener’s idea was that he could not explain how continents could move. Remember that, as far as anyone was concerned, Earth’s crust was continuous, not broken into plates. Thus, any mechanism Wegener could think of would have to fit with that model of Earth’s structure. Geologists at the time were aware that continents were made of different rocks than the ocean crust, and that the material making up the continents was less dense, so Wegener proposed that the continents were like icebergs floating on the heavier ocean crust. He suggested that the continents were moved by the effect of Earth’s rotation pushing objects toward the equator, and by the lunar and solar tidal forces, which tend to push objects toward the west. However, it was quickly shown that these forces were far too weak to move continents, and without any reasonable mechanism to make it work, Wegener’s theory was quickly dismissed by most geologists of the day.

Alfred Wegener died in Greenland in 1930 while carrying out studies related to glaciation and climate. At the time of his death, his ideas were tentatively accepted by a small minority of geologists, and firmly rejected by most. But within a few decades that was all to change.

Video: Geoscience Videos – Continental Drift

Resources

On The Shoulders of Giants: Alfred Wegener

References

Wegener, A. (1920). Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane. Braunschweig, Germany: Friedr. Vieweg & Sohn. Full text at Project Gutenberg

Licenses and Attributions

“Physical Geology, First University of Saskatchewan Edition” by Karla Panchuk is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Adaptation: Renumbering, Remixed for clarity