1.2 The Belle Époque: An Era of Sweeping Change

In the previous section, we laughed along with the revelers in Lumière’s “Snowball Fight” and you may have been inspired to learn about social realities present during its filming. With some research and some sociology, the setting and story expand, allowing us to ask more questions.

Late 1800’s France was the center of the Belle Époque, or “Beautiful Epoch” of Europe. It was a time of optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity, and technological, scientific, and cultural innovations. Mass transit was new, education was more available to many, as was art and entertainment. The quality and quantity of food improved, with purchase of spirits increasing by 300%; sugar and coffee by 400%.

Running water, gas, electricity and sanitary plumbing was more available to the middle class. Life expectancy of children rose. Disposable incomes were plentiful enough to enjoy luxurious items such as fashionable clothing and travel. Historians think of this era as full of hedonism, sexual liberation and the fading of social barriers. Literature, music, theater, and the visual arts flourished, especially in Paris. Daily news publications and advertising were expanding immensely.

At the same time, as in all places exploding with change, tension and trouble existed in France. The French feminist newspaper, La Fronde (The Slingshot), was first published in Paris in 1897, the same year that “Snow Fight” was filmed. La Fronde’s founder was inspired by struggles of female workers in match factories, and disheartened with how they were portrayed in the mainstream or “masculine press.” La Fronde publications covered issues of working conditions and equal pay for women. Its articles presented women as knowledgeable and opinionated on topics traditionally only assigned to males (Faiers 2021 and Roberts 2002).

Politics became more divided, with the extremes of the left and right gaining support. Some groups viewed cultural changes afoot as decadent and immoral. While some members of the lower classes experienced improved living conditions, most urban poor still lived in cramped homes, received low wages, and faced terrible working conditions and poor health. Capital punishment was still delivered publically with the guillotine. The status of the Catholic Church was being challenged at this time, and anti-Catholic laws were passed restricting religious instruction in all schools. There was a push to require civil (rather than church) marriages. Divorce emerged in the mainstream consciousness as an option to unhappy unions.

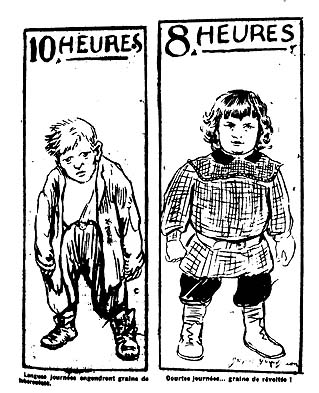

Tuberculosis was a dreaded disease, causing 100,000 deaths annually (Mitchell 1988) and changing society in many ways. Citizens were battling over laws regarding health services, the registration of people who had the disease, and the mandate of quarantines. Tuberculosis was still a concern in the early 1900s, when the newspaper, La Voix du peuple (The Voice of the People) published the two cartoons in figure 1.6. One image shows a sickly worker underneath the words “10 hours” with the caption: “Long days breed the seed of tuberculosis.” The other; a much healthier individual stands underneath the words, “eight hours.” This image clearly identified the dual sentiment of fear of tuberculosis and the campaign for workers’s rights at the time (Barnes 1995).

Figure 1.6. Cartoons printed on page 3 of La Voix du peuple, May 1, 1906 (Barnes 1995). Translated, the caption on the left reads, “Long days breed the seed of tuberculosis.”

How might these social circumstances have shaped the lives of these rowdies of Lyons? For example, considering the progressive representations of women in the media, was it liberating for them to ice-brawl with men in the street? Cinematography had just been made possible. How might this brand-new recording format have shaped their experience that day? Most medical professionals at the time agreed that one was vulnerable to tuberculosis if deprived of air, sunlight, and exercise (Mitchell 1988). Was fear of tuberculosis a partial driver of their participation? How might other social circumstances have shaped the experiences of these snowball fighters?

We can also see patterns between the Belle Époque in France and other social realities across time and place. For example, the United States is currently experiencing a political polarization as well. In 2022, U.S. employees of Starbucks organized the company’s first unions, demonstrating that workers’ struggles are an ongoing social reality. We are reminded that U.S. and European societies have many times struggled with how to deal with pandemics as we are now struggling with COVID-19. It may be universal that during each pandemic some groups rebuke the mandates of governments (such as masks and quarantine) designed to curb the spread of disease.

1.2.1 The Art of Sociology: The Study of Social Change

Sociology is a science guided by the understanding that “the social matters: our lives are affected, not only by our individual characteristics but by our place in the social world, not only by natural forces but by their social dimension.” (The Health of Sociology). Sociologists study the structure and culture of societies. They explore how social groups shape our identities and behaviors. As a social science, sociologists use the scientific method to understand society. That is, they develop and test theories about the social world based on empirical evidence, evidence which is gained by observation or experience.

Sociologists ask the following core questions:

- Why do people behave the way they do?

- How is society organized?

These social realities of 1897 France can also be seen as snapshots of how society was shifting in the country, in Europe, and in the world. These are examples of social change, or the changes in human interactions and relationships that transform cultural and social institutions. In this way, sociology also asks:

- How do societies change and why?

- In what ways do human interactions, behavior patterns, and cultural norms change over time?

Imagine yourself as an adult in France in 1897. How would the social attitudes, circumstances and social changes have influenced your life at the time? How would they have influenced your life if you were a working class Catholic man? An upper class teenager? How would your family have been affected? How would the diverse communities of Lyons be influenced?

1.2.2 The Study of Social Change with an Equity Lens

Sociology also goes further to examine connections that may not be not as easy to see; particularly not as easy to see by the white, upper middle class professionals who still make up the majority of sociologists today. Good sociological study of social change is done with an equity lens. This means recognizing that we do not all receive the same power and resources in society, and acting to address those imbalances by dismantling systems of power, privilege, and oppression.

That is, sociology done with an equity lens pays attention to how changing human interactions, behavior patterns, and cultural norms affect groups who live with less access to opportunities and services, those who experience discrimination, or are the targets of violence and oppression.

For example, the study of social change with an equity lens devotes attention to the impact of social change among Black people, Indigenous people, and People of Color (BIPOC). It inquires about the impact of social change among people who identify outside of the gender binary (the notion that gender is exclusive to being a man or woman). It examines how experiences with social change are felt by people living with disability, as veterans, as new immigrants, or who practice a religion prone to discrimination. Social change can create improved circumstances for members of those groups, or it can exacerbate inequity and violations of civil and human rights.

At the same time, studying social change with an equity lens means being vigilant about identifying the (often hidden) role that members who identify within these groups play in influencing social change. Let’s see how we might expand our study of the Belle Époque with an equity lens.

1.2.3 The Belle Époque as a Person of Color

An internet search of art from the Belle Époque reveals the gaiety, artistry, and playfulness of this time. One good example is in figure 1.7, the painting by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, “At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance’’.

Figure 1.7. Painting titled: At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1890)

However, it is not as easy to find images of people of color from this era in France. We have to study deeper to learn how immigrants from Africa, the Caribbean, and North America lived in European cities at the time. For example, we know that a significant number of Black U.S. immigrants had come to France following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, when the U.S.acquired a large piece of land from the French. Suddenly Black people went from living free in a French territory to living in a state with a policy of segregation and political, social, and economic discrimination against nonwhites. Instead of enduring life under those circumstances an estimated 50,000 free blacks chose to emigrate to France (Beardsley 2013).

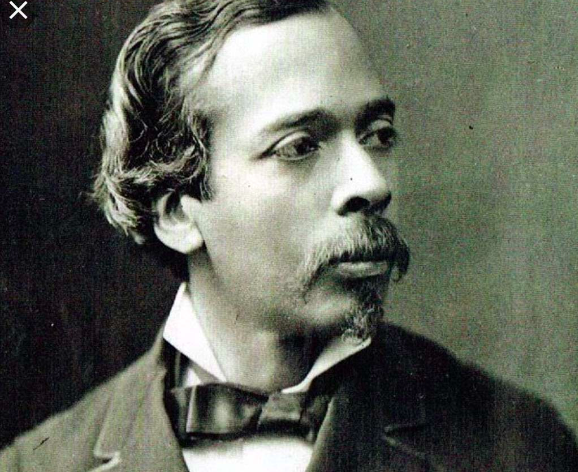

By the Belle Époque, Black people were working in domestic service, as laborers, and seamen; as musicians, dancers, and other entertainers (Childs and Libby 2017). There were also high profile Black individuals of this era in France. While their presence is limited, some have been acknowledged in print. For example, Severiano de Heredia, a Cuban-born biracial politician served in what was the equivalent to the mayoral post in Paris from 1879 to 1880. He was the first mayor of African descent of a Western world capital (Audureau 2020; Triay 2012).

Heredia’s contributions to the progressiveness of the Belle Époque included initiatives to support universal and continuing education, libraries, and ecology. He favored separation of church and state, a free press, women’s rights, and child labor reforms. He is noted for his response to a severe winter during his term, finding shelter for the homeless, and employment for 12,000 Parisiens (Mayeur and Arlette 2001). Heridia also dedicated his work toward the build and improvement of the electric car (Atisu 2019). Heridia, however, did not receive public recognition for his career until 2013 when a walkway was named in his honor in Paris (Triay 2013 and 2015). See an image of Severiano de Heredia in figure 1.8.

What else can we learn about the experiences of people of color at this time?

Figure 1.8. Severiano de Heredia, the first mayor of African descent of a Western world capital, He served in Paris, 1879 -1880.

1.2.4 The Belle Époque as an Algerian

France had recently taken over territories in Vietnam, Cambodia, China, Tunisia, and Gabon, adding to its colonial expansion (Chafer 2002). So, by 1897 immigrant groups from these countries also existed in France. But in 1830 France had also invaded Algeria. Because there were many more settlers in Algeria than other colonies, and due to Algeria’s close proximity, France invested great effort to maintain power and resources there.

After Algeria’s military was conquered, France spent forty years squashing tribal rebellions with campaigns and scorched earth colonization operations, a tactic by which all resources and assets are destroyed or stolen. As a result, Algeria suffered land grabs, wealth extraction, massacres, deportations, famines and epidemics for forty more years. Eventually 825,000 Indigenous Muslims were killed (Phipps 2021).

The colonization and genocide of Algeria was supported by ideas spread by the Catholic church that cast Algerians as racially inferior and socially undeveloped. Muslim practices such as women wearing veils and separation of genders were touted as backwards and in need of intervention, particularly to “save” the Muslim woman. The idea was that a morally and benevolent French rule could modernize and improve their lives. With this rationalization, eventually tens of thousands of Algerians were sold as slaves or brought to France to work in mines (Phipps 2021).

Knowing these bits of history, it is possible to find images of Islamic Algerians under French rule. Many, taken later in the Belle Epoque, are photographs that had been taken for postcards in occupied Algeria and sent back to France for sale. Frequently women were depicted in a way that catered to the romanticized notions that French citizens held of Algerian habits and culture. As author and critical theorist Sarah Sentilles (2017) writes, “ …they imagined them: lounging in harems, smoking hookahs, trapped in the prison of their own homes, topless, sexually available.” (n.p.)

While this was far from reality, and most Algerian Muslim women wore veils in public, the photographers capitalized on the opportunity to provide images suited to these stereotypes. Sentilles (2017) writes:

They hired models, often from the margins of society, and paid them to pose and to wear costumes. In their studios, the photographers used props and backdrops to create bedroom interiors, decorated spaces with hookahs and coffee pots and rugs to look like harems, and placed bars on windows to produce a sense of imprisonment. If Algerian women would not take off their veils voluntarily, the photographers would pay them to do so. (n.p.)

Figure 1.9 is a good example of hundreds of staged photographs taken of Algerian women under French occupation during the 19th century.

Figure 1.9. Staged image of an Algerian woman with hookah

With this background, it’s easier to shape an informed idea of what it would have been like living in Algeria after France invaded. It’s also easier to understand what it would have been like living in France as an Algerian. Most likely we would have emigrated by force or economic need. In all cases, our lives and the lives of our families and community would have been dramatically affected by the social changes that developed due to the occupation.

Making further connections, we can add to the art of sociology by recognizing that the French colonization of Algeria and other countries is related to the wellbeing of many French citizens. The exploitation of resources and people in those foreign countries contributed to the economic prosperity, optimism, and freedom to innovate during the Belle Époque.

1.2.5 Tracing History’s Impact on the Present

Another task crucial to the art of sociology with an equity lens is understanding how social circumstances and social changes in the past influence social dynamics of the present. For example, in France today, full facial veils are banned in public spaces. Likewise, religious head coverings are illegal in schools and government buildings. Proponents say these laws are intended to dampen religious “extremism,” while critics say they unfairly target the country’s minority Muslim population.

In 2021 the French Senate voted to ban girls under eighteen from wearing the hijab in public spaces and give public swimming pools the right to ask women not to wear burkinis, the whole-body swimwear worn by some Muslim women. The amendment sparked a social media campaign including the Instagram image in figure 1.10 posted by model Rawdah Mohamed. Her hashtag #HandsOffMyHijab trended widely.

Figure 1.10. Image of Rawdah Mohamed in her Instagram image, with “Hands off my Hijab” written on her hand.

In 2021, Catherine Phipps, wrote an article that relates France’s colonial past with the country’s increased restrictions on Muslim women wearing veils. She makes these connections:

These efforts to “liberate” Muslim women reiterate attitudes about women’s bodies and religious symbols that are rooted in the history of French imperialism. They echo French justifications for imperialism abroad, which was framed as a “civilizing mission” that masked widespread colonial violence. Such attitudes are rooted in centuries of beliefs of racial superiority and a need to “protect” Muslim women. By recognizing this historical tie, we can see how the overt violence inherent in imperialism is still influencing the daily lives of many Muslim women in France today (Phipps 2021).

In many ways the attitudes, power structures, and discrimination known during Colonial France continue today. Applying an equity lens, what other historical social circumstances and changes can you imagine may have influenced the lives of people in France during the “Snowball Fight” of 1897?

1.2.6 Going Deeper

- For more information on staged images of women in Algeria, see Zara Choudhary’s article, “Unveiling the Algérienne: French Colonial Photography.”

- For more information on how the visual arts imagined Black Europeans people during the nineteenth century read: “The Black Figure in the European Imaginary.”

- For more connections between French Colonialism and current life in France, watch this 13:59-minute video, “France’s Colonial Past and Race Relations Today.”

1.2.7 Licenses and Attributions for The Belle Époque

“The Belle Époque” by Aimee Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.6. Figure 1.6. Cartoons printed on page 3 of La Voix du peuple, May 1, 1906 is in the Public domain. Courtesy of David Barnes/University of California Press.

Figure 1.7. At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance is found in the Public domain via Wikipedia.Courtesy of Google Art Project.

Figure 1.8. Image of Severiano de Heredia is found in the Public domain via the website, Black Past, in the article, “Severiano de Heredia (1836-1901)”.

Figure 1.9: Staged image of an Algerian woman with hookah is found in the Public domain via the website, Sacred Footsteps, in the article, “Unveiling the Algérienne: French Colonial Photography”.

Figure 1.10. Image of Rawdah Mohamed in her post “Hands off my Hijab” written on her hand is found via Instagram and is used with fair use.