9.6 Environmental Justice and Indigenous Movements

While much progress is being made to improve resource efficiency, far less progress has been made to improve resource distribution. Currently, just one-fifth of the global population is consuming three quarters of the earth’s resources. If the remaining four-fifths were to exercise their right to grow to the level of the rich minority it would result in ecological devastation. So far, global income inequalities and lack of purchasing power have prevented poorer countries from reaching the standard of living (and also resource consumption/waste emission) of the industrialized countries.

Countries such as China, Brazil, India, and Malaysia are, however, catching up fast. In such a situation, global consumption of resources and energy needs to be drastically reduced to a point where it can be repeated by future generations. But who will do the reducing? Poorer nations want to produce and consume more. Yet so do richer countries: their economies demand ever greater consumption-based expansion. Such stalemates have prevented any meaningful progress towards equitable and sustainable resource distribution at the international level. These issues of fairness and distributional justice remain unresolved.

9.6.1 Environmental Justice

Thought and action toward environmental justice is a growing and potent social movement (figures 9.47 and 9.48). Environmental justice is defined as the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. With this definition in mind, environmental justice has yet to be actualized.

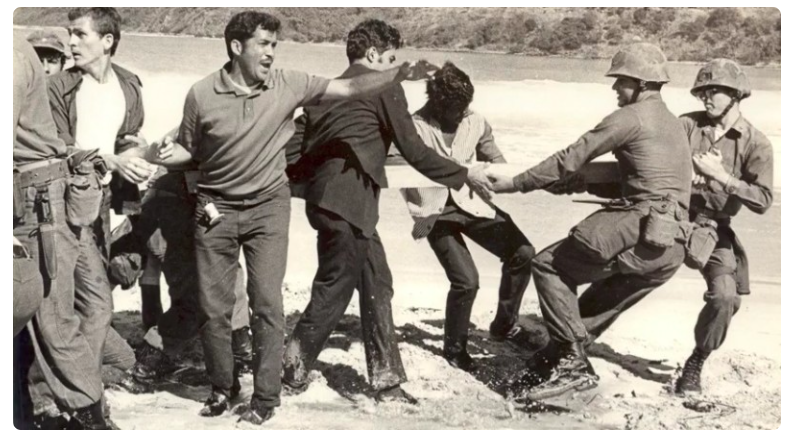

Figure 9.47 and 9.48. Images from the 2nd March of Indigenous Women: Ancestral women: healing minds for the healing of the earth held in Brazil in 2021. Part of their manifesto reads: “We, Indigenous Women, are in many struggles at national and international level. We are seeds planted through our songs for social justice, for the demarcation of territory, for the standing forest, for health, for education, to contain climate change and for the ‘Healing of the Earth’. Our voices have already broken silences imputed to us since the invasion of our territory.”

As we’ve discussed in several chapters of this book, the world we live in is shaped by economic, political, and social values that have been prioritized and imposed by primarily Western countries. Colonization has been a fundamental method for Western countries to establish these values across continents. Colonization is an ongoing process that has subsequently created or emphasized biases, such as environmental racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia. All of these biases intersect with climate-related and resource-use issues.

The economic, political, and social systems that environmental science lives within are based on exponential growth and individualism (a frontier mindset, ego mindset, and anthropocentric mindset). In the United States, we see the devastating consequences of climate change- from extreme wildfires to deadly hurricanes, to the health crisis of COVID-19. These repercussions are not coincidental, they are because of our use and exploitation of natural resources.

The use and benefits of these resources are unequally distributed. And while all of us will experience the aftermath of climate change, not all people will experience it equally (inequality of environmental impact). People of color, especially Black and Indigenous people, and other marginalized individuals and communities are often on the frontlines of climate change and experience the highest intensity of its effects.

The environmental justice movement responds to these realities. It is based on the principle that all people have a right to be protected from environmental issues, and to live in and enjoy a clean and healthful environment. The movement emphasizes that environmental problems cannot be solved without unveiling the practices maintaining social injustices.

9.6.2 Environmental Justice in Action

In the United States, the environmental justice movement emerged in the 1980s and was heavily influenced by the American civil rights movement. Initially it focused on the harm that toxins create for marginalized racial groups within rich countries. Then, topics expanded to include public health, worker safety, land use, transportation, and other issues. Exports of hazardous waste to the Global South escalated through the 1980s and 1990s and became part of the early environmental justice movement as well.

Today, the members of the global environmental justice movement represent a multitude of roles and backgrounds. They include academics who have conducted hundreds of studies that demonstrate how exposure to environmental harm is inequitably distributed. They include members of organizations focused on training leaders and empowering activists to make change locally or globally. Often the aim is to elevate voices of color including indigenous leaders. This builds a more diverse and inclusive movement and relies on the lived experience, expertise of the issues as well as first-hand innovative ideas for solving them.

Issues that environmental justice actors address include environmental racism and discrimination associated with hazardous waste disposal, and land appropriation. They also often work on human rights abuses that occur when companies extract resources. The human rights abuses involving land grabs and resource extraction invariably result in the loss of land-based traditions and economies. In response, local environmental defenders will frequently confront multinational corporations involved with resource extraction or other industries that harm the environment. Those working for environmental justice also seek to expand the scope of human rights law which historically has not been able to adequately address the relationship between the environment and human rights.

9.6.2.1 The U.S. Navy, Hazardous Waste, and Hurricane Katrina in Puerto Rico

Figure 9.49. A rusting carcass of an M4 Sherman tank left behind by the U.S. Navy on a beach on Culebra Island, Puerto Rico. A little known hazardous waste act was that of the U.S. Navy depositing contaminants in the form of exploded and unexploded artillery on beach areas in Puerto Rico (figure 9.49). Culebra Island was allocated to the U.S. Navy in 1901 to use for test landings and ground maneuvers, then later for bombing practice. Many armaments were moved there, and bombing practice lasted for decades. Locals protested nonviolently with marches and civil disobedience campaigns in the form of sit-ins, and blockades, especially when the military attempted to evacuate the entire population in 1970 (figure 9.50). However, military exercises were also being conducted on the nearby island of Vieques, Puerto Rico. After more years of efforts of social movements and individuals across the political spectrum, the Navy agreed to phase out their use of the island as a testing ground.

Figure 9.50. Islanders of Culebra, Puerto Rico confront the Navy to protest the island being used as a testing ground. After the base was closed Vieques was designated a superfund clean-up site. Environmental groups and residents of Vieques expressed that the Navy caused “more damage than any other single actor in the history of Puerto Rico” (Herbert 2001: 23). A 1977 survey by the Puerto Rico Health Department revealed that the cancer rate in Vieques was 27% higher than mainland Puerto Rico (Pelet 2016). In 2021 the U.S. Government Accountability Office reports that the Department of Defense [DOD] continues to clean the munitions and hazardous substances that have been left in Vieques and Culebra, with significant work still to be done. They estimate that by the time they have completed the clean-up they will have spent nearly $800 million (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2021).

Figure 9.51. Oct. 9, 2017, Naval Aircrewman and local volunteers unload water from an MH-60S SeaHawk helicopter as part of relief efforts to Vieques, Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. In addition to being a case study of social movements, Puerto Rico is a case study in environmental inequality of impact. The island was hit hard by Hurricane Maria in 2017 (figure 9.51). Residents had already been struggling due to crumbling infrastructure; outside investors purchasing property, land, and resources; and less access to opportunity for women (Babic 2022). Poverty in Puerto Rico is high. The 2021 Census measured the island’s poverty rate at 42%. In comparison, this is much much higher than the U.S. national rate of 13.1% (The United States Census Bureau Quick Facts n.d.). |

A good place to get information on issues surrounding environmental justice is the Racial Equity Tools site, and their Environmental Justice Page. Spend a few minutes browsing through the resources and projects there. In what ways do you see researchers, activists and organizations addressing environmental justice?

Figure 9.52. Linkable image to the Racial Equity Tools page.

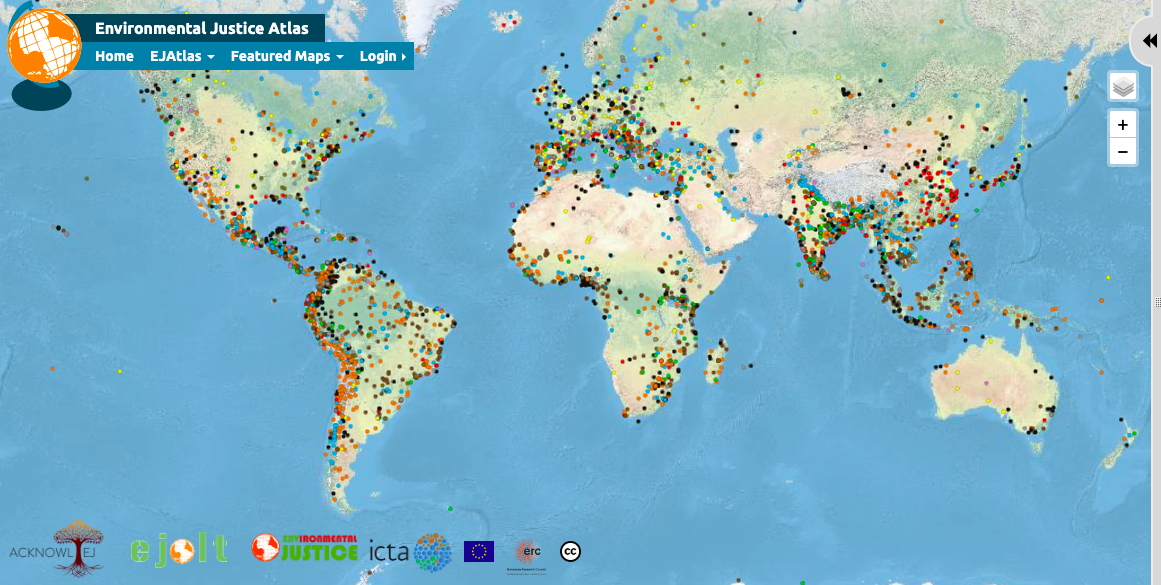

An example of a project on the global level is the Environmental Justice Atlas (figure 9.47). It’s a tool developed by professors in Spain that documents and catalogs social conflict around environmental issues around the world. It’s a resource for teaching, networking and advocacy around events, concerns, and action related to environmental justice. Take a few minutes to browse the atlas to get an idea of the kinds of environmental conflicts and issues they are tracking.

Figure 9.53. Linkable image to the Environmental Justice Atlas.

9.6.3 Indigenous Led Environmental Movements

What does environmental justice look like when it is put into practice best? What social movements are pushing the envelope toward relief for the most vulnerable and equity in solutions? One effective way of actualizing environmental justice, while deepening our understanding of environmental systems, is by recognizing and supporting the many ongoing Indigenous struggles that exist today.

9.6.3.1 Indigenous Struggle and Knowledge

As a result of colonization, Indigenous people make up only five percent of the population worldwide but manage and support 80 percent of global biodiversity. While the traditions, languages, and beliefs of Indigenous people vary tremendously across the world, this statistic points to a common value that is seen in Indigenous cultures: the emphasis on protecting and stewarding of their environments.

Many Indigenous cultures have intimate connections to the land, water, and ecosystems that they have a relationship to. This leads to a deep understanding of their environment and their own impacts on the systems that they rely on. It also leads to values of what non-Indigenous cultures call sustainability. The focus is on taking care of and managing resources in order for future generations to live in prosperity and preserve their cultures and traditions.

Figure 9.54a. Logging, both legal and illegal, has broken up and degraded the Amazon rainforest in Brazil to the point where now the ecosystem and species populations are fragmented, and wildfires rage in places that were until recently always humid. Map shows an intact area of forest on the Arariboia Indigenous land in northeast Brazil, home to the Guajajara and Awá Indigenous Peoples, in stark contrast with the degraded rainforest surrounding it. © Google Maps.

Figure 9.54b. The Karipuna people, also indigenous to the Amazon Rainforest, were reduced by infrastructure incursion into their land, social conflicts, and contagious diseases to a population of just 8 people in the 1970s and 80s. Illegal logging as well as a hydroelectric project were drastically impacting their lands and home, and violent threats were made to their elders and leaders. Through international advocacy, their own powerful leadership, and collaboration with other indigenous people in their area, they have managed to dramatically reduce the logging and raise awareness worldwide. © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace

Currently, our economic, political, and social systems in Western-dominated countries do not share or reflect these values. This is one of the major contributing factors that has led to intense environmental degradation on small and large scales. Indigenous struggles that exist today reflect and address the underlying problems within Western-dominated societies, such as the United States. Some examples of these struggles include, but are not limited to:

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

- Deforestation

- Water protection

- Anti-fossil fuel extraction

- Food sovereignty

- Language revitalization

- Land rematriation

While not all Indigenous people fight for or align with these issues, all of these issues apply to the practice of environmental justice. For centuries, most Indigenous people across the world have been stewarding the land of their ancestors while simultaneously creating complicated and developed cultures, civilizations, and traditions. These societies and ways of life coexisted and continue to coexist with the natural world around them.

For these reasons, the project of environmental science, of understanding complex environ- mental systems and their interactions with our own human systems, is currently seen by some people as inextricably linked to environmental equality, and specifically to the survival and leadership of indigenous communities. And if we wish to live in a world that is environmentally just, then we must center the struggles and knowledge of Indigenous peoples.

9.6.3.2 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems hold the key to feeding humanity

One movement that is centering both the struggles and knowledge of Indigenous peoples relates to food systems. As climate change advances, and natural resources shift, we need to pay attention to how we’ll feed ourselves as a global community. The unsustainable food systems we have in place now are becoming impacted by rising air and water temperatures, sea levels, and changes in rainfall patterns. Resulting changes in soil fertility and crop yields affect the base of our food source. However, there’s promise in a social movement that looks to Indigenous people’s food systems.

A recent workshop hosted by the International Institute for the Environment and Development (IIED) and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew explored the way Indigenous Peoples grow and consume food.

Figure 9.55. Celebrating the spirit of the potato. In Peru, the Potato Park – a Quechua biocultural heritage territory – donated a ton of potatoes to people in need in Cusco city during the COVID-19 crisis (Photo: Asociacion ANDES).

Modern food and farming systems are fundamentally unsustainable. They contribute around a third of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions and are responsible for almost 60% of global biodiversity loss. They are degrading the natural resources – water, soils, genetic resources – needed to sustain agricultural production.

Modern food systems (PDF) are also highly inequitable, with power and wealth concentrated in the hands of a few corporations. Despite increased yields, food insecurity has been rising in recent years – more than 820 million people are hungry and 2 billion people are food insecure, underscoring the immense challenge of achieving the second Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of zero hunger by 2030.

The food systems of the world’s 476 million Indigenous Peoples are often branded as ‘backward’ or unproductive – but evidence shows they are highly productive, sustainable and equitable. These systems preserve rich biodiversity, provide nutritious food and are climate resilient and low carbon. And they are already achieving zero hunger for many Indigenous Peoples, as research by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has shown.

This study also found that Indigenous Peoples engaged in traditional activities in remote, biodiverse areas with little reliance on market economies tend to be of normal weight; and that supporting Indigenous Peoples’ food systems and self-determination enhances nutrition and health.

Many neglected and underutilized species that Indigenous Peoples cultivate are nutrient-dense. By contrast Indigenous Peoples who have shifted to modern diets are facing growing health problems (such as obesity and diabetes). Indigenous Peoples’ food systems also have a critical role to play in informing wider transitions to sustainable and equitable food systems.

9.6.3.2.1 Indigenous food systems address multiple SDGs

Earlier this month, Indigenous Peoples from Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Arctic, academic institutions and UN agencies joined a virtual workshop (PDF) – co-hosted by IIED and Kew – to examine the role of Indigenous Peoples’ food systems and interlinked biological and cultural heritage – or biocultural heritage – in achieving the SDGs.

Indigenous representatives stressed that their ancestral food systems, based on centuries of accumulated wisdom, are not only crucial for food security and food sovereignty, but also for cultural identity, spiritual well-being, and land stewardship. Indigenous Peoples conserve about 80% of the world’s biodiversity and represent most of the world’s cultural diversity.

Many Indigenous Peoples are reviving their agroecological food systems because they are more resilient to climate change and provide more nutritious diets than modern food systems. And they have proven vital during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exposed the vulnerability of global food chains.

Participants heard how, in Kenya, Indigenous seeds – regarded by the Tharaka tribe as sacred – have helped to lessen the impacts of COVID-19 by promoting social cohesion through cultural ceremonies; in Peru, the Potato Park – a Quechua biocultural heritage territory – has donated a ton of potatoes to people in need in Cusco city during the crisis.

9.6.3.2.2 In balance with nature

In a live-streamed session from the high Andes, Quechua communities in the Potato Park explained how their Indigenous food system ensures food security despite climate change, and sustains exceptionally high potato diversity, thanks to their ancestral values of reciprocity, solidarity and balance (in society and with nature).

These outcomes are fundamentally due to their ancestral knowledge and holistic worldviews – but are enhanced by respectful research with scientists.

Indigenous food systems from Chad to China are based on ‘seven generation thinking’ – that seeks to ensure future food security. They sustain not only locally adapted Indigenous and traditional crops, but also wild foods and crop wild relatives that Indigenous Peoples from Peru to the Philippines use to enrich their domesticated crops.

Indigenous participants also highlighted the economic importance of Indigenous food systems. In Chad, pastoralism contributes about 40% of GDP, in Kenya, COVID-19 is fuelling a revival of traditional foods while in the Potato Park, communities have developed a range of micro-enterprises – traditional weaving, medicinal plants, traditional restaurant, eco-tourism – that generate income and support the poorest people.

9.6.3.2.3 Undermined, overlooked, under threat

But workshop participants identified many challenges facing Indigenous food systems, including the rapid loss of Indigenous knowledge and the destructive impacts of policies and programmes promoting industrial agriculture. Indigenous Peoples are largely left out of policy discussions and face widespread marginalization and racial discrimination.

Failure to recognise Indigenous Peoples’ rights to natural resources and land is a major threat to Indigenous food systems. In northern Thailand, Karen Indigenous farmers can be imprisoned for practicing rotational farming even though research has shown this method is sustainable, biodiversity-rich and important for food security; in Northeast India, forest policies that restrict the use of ancestral Lepcha forests are undermining biodiversity-rich Indigenous food systems and promoting a shift to cash crops.

In Chad, land that is vital for sustaining highly resilient and biodiverse pastoralist food systems is being sold off, while in the Arctic region of Russia, industrial development has almost destroyed a traditional food culture of hunting and fishing that is essential for survival.

9.6.3.2.4 Indigenous-led research must feed into 2021 summit

More research is urgently needed to address the many challenges facing Indigenous food systems – research that recognises Indigenous Peoples as experts, values Indigenous knowledge and science equally, is led by Indigenous Peoples and draws on different disciplines.

Research priorities include protecting Indigenous land and resource rights; preserving endangered agrobiodiversity and Indigenous knowledge systems; and exploring women’s roles and health and traditional restaurants and cuisine that are crucial for sustaining traditional crops.

Governments and UN agencies must reform agriculture, forest and economic policies that threaten Indigenous food systems, with the active participation of Indigenous Peoples. And they must actively engage Indigenous Peoples in the preparatory process for the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit and in the summit itself.

9.6.3.3 Going Deeper

To learn more about Indigenous food sovereignty, read HARVESTING is an Act of Indigenous Food Sovereignty.

To learn more about indigenous knowledge and climate change read “To share or not to share? Tribes risk exploitation when sharing climate change solutions.”

9.6.4 Licenses and Attributions for Environmental Justice and Indigenous Movements

“Environmental Justice and Indigenous Led Movements” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0. The introductory paragraphs is adapted from Essentials of Environmental Science by Kamala Doršner, licensed under CC BY 4.0 and modified from the original by Matthew R. Fisher.

“Environmental Justice” is a remix of “1.5 Environmental Justice & Indigenous Struggles” by Avery Temple, is found in “Terrestrial Knowledge” licensed under CC BY 4.0. Images have been added.

“Indigenous Led Environmental Movements” includes “Indigenous Peoples’ food systems hold the key to feeding humanity” is a blog written by Krystyna Swiderska and Philippa Ryan and published by the International Institute for Environment and Development on 23 October 2020 under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. The blog includes figure 9.55 and its caption.

Figure 9.47. Image from the 2nd March of Indigenous Women: Ancestral women: healing minds for the healing of the earth is a screenshot from the web page of The National Articulation of Indigenous Women Ancestrality Warriors (ANMIGA) and is published here under Fair Use.

Figure 9.48. Image from the 2nd March of Indigenous Women: Ancestral women: healing minds for the healing of the earth is provided by Apib Comunicação and published on Wikimedia Commons under (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Figure 9.49. A rusting carcass of an M4 Sherman tank left behind by the U.S. Navy on a beach on Culebra Island, Puerto Rico is provided by JohnnyPicture and published on Wikimedia Commons under (CC BY 3.0).

Figure 9.50. Islanders of Culebra, Puerto Rico confront the Navy to protest the island being used as a testing ground is a screenshot from the Spanish language documentary, “Culebra 135-40“, produced by the Puerto Rican monthly Diálogo UPR. The screenshot is published on the website, Global Voices under (CC BY 3.0).

Figure 9.51. 10 Oct. 9, 2017, Naval Aircrewman and local volunteers unload water from an MH-60S SeaHawk helicopter as part of relief efforts to Vieques, Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. This U.S. Navy Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Jacob A. Goff is published on Flickr under (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Figure 9.52. Linkable image to the Racial Equity Tools page is a screenshot of the same website included here under Fair Use.

Figure 9.53. Linkable image to the Environmental Justice Atlas is a screenshot from the same web page and is used here under Fair Use.

Figure 9.54a. Logging, both legal and illegal, has broken up and degraded the Amazon rainforest in Brazil…is found published in © Google Maps.

Figure 9.54b. The Karipuna people, also indigenous to the Amazon Rainforest is provided by © Rogério Assis / Greenpeace.