6.2 Institutions Designed for Health and Safety

In Chapter 2, we discussed how institutions are the structures in society which define the way we interact with each other. Let’s look into the three intersecting institutions whose weaknesses were revealed in 2020: government, health care, and social services. Health care and social services are intended to provide safety and attention to good health. Government provides the policy and funding for safety and health to be fulfilled. We can begin by exploring how these institutions have come to be. This will provide a basis of understanding for you to examine the realities of these institutions later on in this chapter.

6.2.1 Healthcare Systems

In the United States our institutions dedicated to health create an elaborate system designed to provide care to residents and support their survival. In one part of the system we have health care providers delivering care and services through private insurance companies. That care via insurance is delivered to individuals and families directly, through employers, or as a public service. Another part of the system involves practitioners providing care outside of the insurance system. These professionals tend to be alternative health care providers such as naturopathic doctors or acupuncturists. Yet another part of that system includes the care that members of society offer for each other outside of a payment transaction, such as parents and community members providing for a sick child at home. As a whole, the system we’ve created in the United States holds the same purpose as any other health institution: to promote, restore, and maintain health.

6.2.1.1 Medical Sociology

The healthcare institutions within the United States are greatly influenced by our cultural and social ideas of health and illness. Sociology; particularly the field of medical sociology has identified the underlying cultural and societal beliefs that have shaped health institutions today.

If sociology is the systematic study of human behavior in society, medical sociology is the systematic study of how humans manage issues of health and illness, disease and disorders, and healthcare for both the sick and the healthy. Medical sociologists study the physical, mental, and social components of health and illness. Major topics for medical sociologists include the doctor/patient relationship, the structure and socioeconomics of healthcare, and how culture impacts attitudes toward disease and wellness.

Sociologists Conrad and Barker (2010) offer a comprehensive framework for understanding the major findings of the last fifty years of development in this concept. Social scientists examine health and its findings in the field under these three categories: the cultural meaning of illness, the social construction of the illness experience, and the social construction of medical knowledge.

6.2.1.2 The Cultural Meaning of Illness

Many medical sociologists contend that illnesses have both a biological and an experiential component, and that these components exist independently of each other. Our culture, not our biology, dictates which illnesses are stigmatized and which are not, which are considered disabilities and which are not, and which are deemed contestable (meaning some medical professionals may find the existence of this ailment questionable) as opposed to definitive (illnesses that are unquestionably recognized in the medical profession) (Conrad and Barker 2010).

Figure 6.4. Erving Goffman

Figure 6.5. Image of Erving Goffman’s book, published in Asylums; Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates

For instance, sociologist Erving Goffman (1963) (figures 6.4 and 6.5) described how social stigmas hinder individuals from fully integrating into society. Stigmatization is the labeling or spoiling of an identity, which leads to ostracism, marginalization, discrimination, and abuse. In essence, Goffman (1963) suggests we might view illness as a stigma that can push others to view the illness in an undesirable manner.

The stigmatization of illness often has the greatest effect on the patient and the kind of care he or she receives. Many contend that our society and even our healthcare institutions and society at large discriminate against certain diseases—like mental disorders, AIDS, venereal diseases, and skin disorders (Sartorius 2007). Facilities for these diseases may be sub-par; they may be segregated from other healthcare areas or relegated to a poorer environment. The social stigma related to a disease or diseases may keep people from seeking help for their illness, making it worse than it needs to be.

Contested illnesses are those that are questioned or questionable by some medical professionals. Disorders like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome may be either true illnesses or only in the patients’ heads, depending on the opinion of the medical professional. This dynamic can affect how a patient seeks treatment and what kind of treatment they receive.

6.2.1.2.1 Stigmatization with mental illness and harmful drug use

One good way to see how illness is culturally informed is with attitudes of mental illness. In the United States, mental illness is severely stigmatized. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, less than half of people with mental illness receive help for their disorders (The National Alliance on Mental Illness 2022). As a result, people avoid or delay seeking treatment due to concerns about being treated differently or fears of losing their jobs and livelihood. Even more devastating, this stigma often also leads to the criminalization of people suffering from mental health crises. The National Alliance on Mental Illness reports:

People with mental illness are overrepresented in our nation’s jails and prisons. About 2 million times each year, people with serious mental illness are booked into jails. Nearly 2 in 5 people who are incarcerated have a history of mental illness (37% in state and federal prisons and 44% held in local jails).

Many people with mental illness who are incarcerated are held for committing non-violent, minor offenses related to the symptoms of untreated illness (disorderly conduct, loitering, trespassing, disturbing the peace) or for offenses like shoplifting and petty theft (National Alliance on Mental Illness n.d.: n.p)

While stigmatization exists in most parts of the world, there are communities that value it differently. Malidoma Somé was an elder and spiritual leader from the nation of Burkina Faso and the cultural region of Dagara, which covers areas of Ghana, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire.

In a video, Somé spoke about his experiences visiting a psychiatry health hospital.

He noted the stark contrast between how the patients there were treated and how people experiencing mental health challenges are treated In Dagara Land. “In Dagara land, when someone nuts; goes crazy, people are really happy. They realize that: ‘we are going to have another healer; we’re gonna have an additional expert to help us’”. Watch the 5:01-minute video, “Answering the Healers Call” in figure 6.6. As you do, pay attention to the meaning that the Dagara people hold for mental and spiritual struggles and those who experience them.

Figure 6.6. Answering the Healers Call – Short [YouTube Video]

In the U.S. the same degree of stigma is applied to harmful drug use. In the case of harmful drug use, that stigma often carries connotations of character and morality, despite the efforts of drug and alcohol counselors and other support practitioners to convey it as an illness. Both those suffering from mental health challenges and those suffering from harmful drug use suffer discrimination based on these stigmas.

6.2.1.3 The Social Construction of the Illness Experience

The social construction of health is a major research topic within medical sociology. The idea of the social construction of the illness experience is based on the concept of reality as a social construction we reviewed in Chapter 2. At first glance, the concept of a social construction of health does not seem to make sense. After all, if disease is a measurable, physiological problem, then there can be no question of socially constructing disease, right? Well, it’s not that simple. The idea of the social construction of health emphasizes the socio-cultural aspects of the discipline’s approach to physical, objectively definable phenomena.

In other words, “what we take to be the truth about the world importantly depends on the social relationships of which we are a part” (Gergen 2018:7). The social construction of the illness experience deals with such issues as the way some patients control the manner in which they reveal their diseases and the lifestyle adaptations patients develop to cope with their illnesses.

In terms of constructing the illness experience, culture and individual personality both play a significant role. For some people, a long-term illness can have the effect of making their world smaller, more defined by the illness than anything else. For others, illness can be a chance for discovery, for re-imaging a new self (Conrad and Barker 2007). Culture plays a huge role in how an individual experiences illness. Widespread diseases like AIDS or breast cancer have specific cultural markers that have changed over the years and that govern how individuals—and society—view them. Cultural markers are shared features such as language and common values in a cultural group that help define the group.

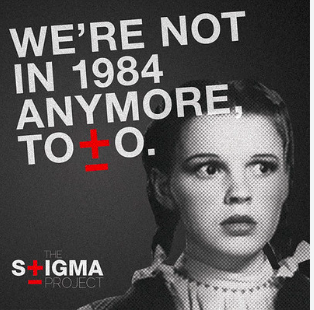

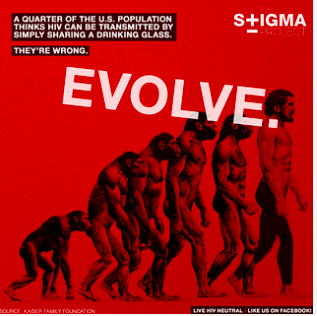

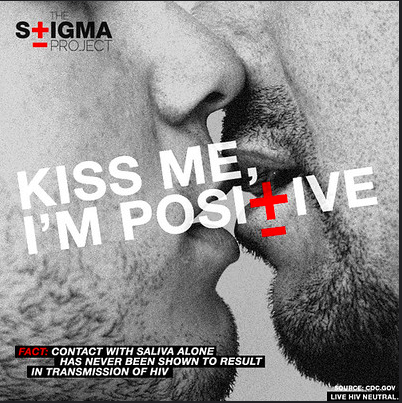

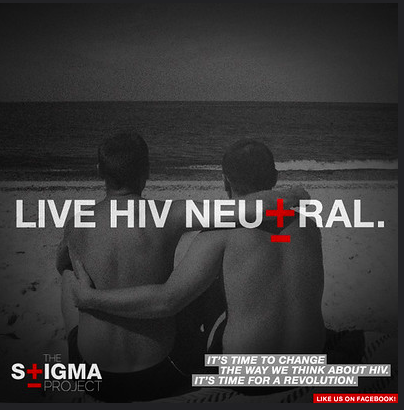

There has been an especially profound shift in how AIDS is experienced culturally. When the disease swept the world in the 1980’s it carried profound negative cultural associations around sexual behavior. Over time, attitudes have shifted, in part due to organizations like The Stigma Project that uses social media and advertising to promote shifts in attitudes around the disease (Figures 6.7 a-d).

Figures 6.7a-d advertisements from The Stigma Project

Today, many institutions of wellness acknowledge the degree to which individual perceptions shape the nature of health and illness.

6.2.1.4 The Social Construction of Medical Knowledge

Conrad and Barker also show how medical knowledge is socially constructed; that is, it can both reflect and reproduce inequalities in gender, class, race, and ethnicity. Conrad and Barker (2011) use the example of the social construction of women’s health and how medical knowledge has changed significantly in the course of a few generations. For instance, in the early nineteenth century, pregnant people were discouraged from driving or dancing for fear of harming the unborn child, much as they are discouraged, with more valid reason, from smoking or drinking alcohol today.

6.2.2 Social Service Institutions

Social service institutions are all around us. They can take the form of public assistance and welfare, (such as food stamps, medicaid and unemployment), the U.S. incarceration system and military, and resource management and public planning. Typically, social services are paid for by the taxes and labor of those residing within a particular country. They promote the health and well-being of individuals by helping them to become more self-sufficient; strengthening family relationships; and restoring individuals, families, groups, or communities to successful social functioning.

6.2.2.1 Public Assistance and Welfare

Efforts to enhance or secure social welfare predate the existence of any professional activity that might be considered social work. Since the United States is still a relatively young country, we draw the beginnings of our attempts at social welfare back to one of the main colonial presences of this country, England. Several of the early attempts at providing assistance for the poor and insurance against social problems that were developed in England had equivalent movements in the United States—sometimes simultaneously, sometimes after a delay of some years.

Before there were government efforts to assist the poor, such tasks were typically handled by feudal landowners. In some of those cases, churches and charity organizations provided basic needs. Government was reluctant to get involved in addressing the plight of those in poverty; some people were concerned—much like today—that providing assistance would cause people to become dependent upon the government and lose any incentive to work their way out of poverty themselves.

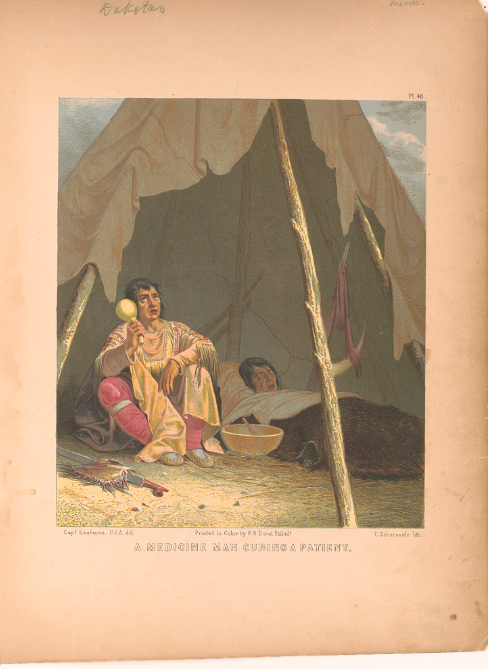

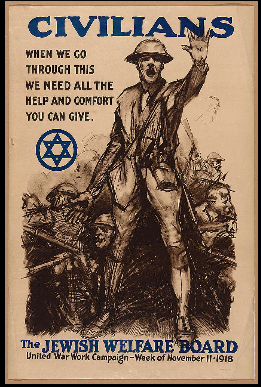

As stated earlier, public assistance and systems for managing the welfare of community members has been present in societies for as far back as humanity has existed. To this day, many cultures and communities practice alternative forms of public welfare. Some of these practices are not based upon monetary trade but rather are intrinsically built into their systems. Others are based on a system of reciprocity. Later on in this chapter, we will explore these alternatives at length. Figures 6.8a-e show a collage of posters and photos from the Library of Congress categorized as “welfare”. In what diverse ways is welfare demonstrated in the collage?

Figure 6.8a Child welfare exhibit Coliseum, May 11-25… (1911). Perkins, Lucy Fitch, 1865-1937, artist

Figure 6.8b Give to the needy Join the mayor’s welfare milk fund : Monster vaudeville show at the Laurel Theatre (1936-9) Poster announcing vaudeville show to raise funds for the needy through New York City Mayor Edwards’ milk fund, showing a large bottle of milk

Figure 6.8c A medicine man curing a patient / Capt. Eastman, U.S.A. (1850-1875?)

Figure 6.8d Civilians, when we go through this we need all the help and comfort you can give – . Poster showing a soldier reaching out above the chaos of battle.The Jewish Welfare Board / Riesenberg, Sidney H., artist (1918)

Figure 6.8e “The custom of the Central Asians. Reading the patient” (between 1865 and 1872).

6.2.2.1.1 The U.S. Criminal Justice System and Military

The criminal justice system is an organization that exists to enforce the laws and legal codes of the United States. There are four branches of the U.S. criminal justice system: the police, the courts, incarceration system, and the military.

6.2.2.1.2 Police

Police are a civil force in charge of enforcing laws and public order at a federal, state, or community level. No unified national police force exists in the United States, although there are federal law enforcement officers and the Coast Guard branch of the military can be utilized to enforce laws or restrictions when declared federally. Federal officers operate under specific government agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI); the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF); and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

6.2.2.1.3 Courts

Once a crime has been committed and a violator has been identified by the police, the case goes to court. A court is a system that has the authority to make decisions based on law. The U.S. judicial system is divided into federal courts and state courts. As the name implies, federal courts (including the U.S. Supreme Court) deal with federal matters, including trade disputes, military justice, and government lawsuits.

State courts vary in their structure but generally include three levels: trial courts, appellate courts, and state supreme courts. In contrast to the large courtroom trials in TV shows, most noncriminal cases are decided by a judge without a jury present. Traffic court and small claims court are both types of trial courts that handle specific civil matters.

Criminal cases are heard by trial courts with general jurisdictions. Usually, a judge and jury are both present. It is the jury’s responsibility to determine guilt and the judge’s responsibility to determine the penalty, though in some states the jury may also decide the penalty. Unless a defendant is found “not guilty,” any member of the prosecution or defense (whichever is the losing side) can appeal the case to a higher court.

6.2.2.1.4 Incarceration System

The incarceration system, more commonly known as the criminal justice or corrections system, is charged with withholding individuals from the public who have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced for a criminal offense. At the end of 2010, approximately seven million U.S. men and women were behind bars (BJS 2011d).

Prison is different from jail. A jail provides temporary confinement, usually while an individual awaits trial or parole. Prisons are facilities built for individuals serving sentences of more than a year. Whereas jails are small and local, prisons are large and run by either the state or the federal government.

Parole refers to a temporary release from prison or jail that requires supervision and the consent of officials. Parole is different from probation, which is supervised time used as an alternative to prison. Probation and parole can both follow a period of incarceration in prison, especially if the prison sentence is shortened.

6.2.2.1.5 Military

The military in the United States is federally referred to as the United States Armed Forces and consists of six branches: the Army, Marine Corp, Air Force, Navy, Coast Guard and Space Force. In theory, the military is a public safety measure that sanctions borders, enforces diplomatic agreements on behalf of the United States government, and goes to war on behalf of the general public when necessary.

The United States currently has the largest military budget in the world. The military takes in an astounding seven hundred billion USD from taxpayers every year, surpassing China’s military budget by nearly five billion USD.

6.2.3 Government as a Social Institution

Government is the institution by which a society organizes itself and allocates authority in order to accomplish collective goals and provide benefits that the society as a whole needs. Goals that governments around the world seek to accomplish include providing economic stability for the nation, enforcing national borders, and securing the safety and well-being of citizens.

Governments also ideally provide benefits for their citizens. The type of benefits provided differ according to the country and their specific type of governmental system, but governments commonly provide such things as education, health care, and an infrastructure for transportation.

Government and capitalism developed together in the United States. Many Americans tend to equate democracy, a political system in which people govern themselves, with capitalism. Democracy is a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state. In theory, a democratic government promotes the freedom to act as communities choose instead of being controlled, for good or bad, by government. Capitalism, however, relies on individualism and consumption.

Democracy and capitalism do not necessarily go hand in hand, however. Indeed, one might argue that a capitalist economic system might be bad for democracy in some respects. Although 18th Century economist Adam Smith theorized that capitalism would lead to prosperity for all, this has not necessarily been the case. Great gaps in wealth between the owners of major businesses, industries, and financial institutions and those who work for others in exchange for wages exist in many capitalist nations. In turn, great wealth may give a very small minority great influence over the government—a greater influence than that held by the majority of the population.

In the United States, the democratic government works closely together with its capitalist economic system. In an ideal world, people can purchase what they need in the quantity in which they need it. In reality, those who live in poverty cannot always afford to buy enough food and clothing to meet their needs, or the necessities that they can afford to buy in abundance are of inferior quality. For example, it is often difficult to find adequate housing. Housing in the most desirable neighborhoods— those that have low crime rates due to having more resources and wealth—is often too expensive for poor, working-class and sometimes middle-class people to buy or rent.

Thus, the market cannot provide everything (in enough quantity, at good enough quality, or at low enough costs) in order to meet everyone’s needs. Therefore, some goods are provided by the government. Such goods or services that are available to all are called public goods. Two such public goods are national security and education. Government is typically thought of as necessary to a nation, because only governments can tax, drawing upon the resources of an entire nation. Also, governments can compel citizen compliance.

What other public goods does government provide in the United States? At the federal, state, and local level, government is meant to provide stability and security. At present this takes the form of a military and also police, prisons and border control. The question of whether or not militaries, police, and prisons offer adequate protection and safety to all residents within the United States will be explored later on in this chapter. Further, governments are theoretically meant to provide other valuable goods and services such as public education, public transportation, mail service, and food, housing, and health care for the poor. While that may be true in some countries, access to resources and these kinds of public goods vary drastically. In the United States access varies from state to state, from city to city, and along racial and ethnic lines.

6.2.3.1 Going Deeper

To better understand how mental illness is criminalized in the United

States, watch the 22:18-minute video, “Mental Illness in America”

National Alliance for Mental Health Infographic: Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System

6.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Institutions Designed for Health and Safety

“Institutions Designed for Health and Safety” written by Avery Temple is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Except:

Public Health Institutions Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License

(credit: soc 200 text – This entire section with reorganization edits and additions. Except for

Public Health Institutions Social Service Institutions CC BY 3.0 License

Government as a Social Institution Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License

Credit these sections to Soc 2e

https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8423

Medical Sociology

Cultural Meaning of Illness

The Social Construction of the Illness Experience

The Social Construction of the Medical Knowledge

Public Assistance and Welfare

Government as a Social Institution

To the above, we’ve made minor revisions and added content.

Attribute to Aimee:

Stigmatization with mental illness and harmful drug use

The role of Public Health Institutions

Figure 6.4. Erving Goffman

Figure 6.5. Image of Erving Goffman’s book, published in Asylums; Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates

Figure 6.6. Title of Video: “ “Answering the Healers Call”

Figure 6.7a Image (Toto) The Stigma Project

Figure 6.7b Image (Evolve) The Stigma Project

Figure 6.7c Image (Kiss Me) The Stigma Project

Figure 6.7d Image Live Neutral The Stigma Project

Figure 6.8a Child welfare exhibit Coliseum, May 11-25… (1911). Perkins, Lucy Fitch, 1865-1937, artist

Figure 6.8b Give to the needy Join the mayor’s welfare milk fund : Monster vaudeville show at the Laurel Theatre (1936-9) Poster announcing vaudeville show to raise funds for the needy through New York City Mayor Edwards’ milk fund, showing a large bottle of milk.

Figure 6.8c A medicine man curing a patient / Capt. Eastman, U.S.A. (1850-1875?)

Figure 6.8d Civilians, when we go through this we need all the help and comfort you can give – . Poster showing a soldier reaching out above the chaos of battle.The Jewish Welfare Board / Riesenberg, Sidney H., artist (1918)

Figure 6.8e “The custom of the Central Asians. Reading the patient” (between 1865 and 1872).