9.4 Environmental Inequality and Inequity

Sociologists emphasize two important dimensions of the relationship between society and the environment. The first, as we described in the section above, is the impact of human activity and decision making. Environmental sociologists emphasize that environmental problems are the result of human decisions and activities that harm the environment. In the examples of environmental problems we’ve reviewed, the human factor is obvious: our personal behavior, the actions of corporations, and the weakness of government environmental regulation cause serious environmental problems that threaten the planet.

The second emphasis that sociologists make is the existence and consequences of environmental inequality and inequity. Recall from Chapter 2 that both globally and locally, our wellbeing is related to our social place (our intersecting racial, ethnic, and gender characteristics). Our social place influences our access to all kinds of resources related to the environment, such as access to open spaces and nature (figure 9.27), access to clean water, or access to safe places during weather emergencies.

Figure 9.27. Photographer Rick Schwartz created this merged photo from images in Central Park, Manhattan, New York City. Schwartz finds that “The park is a peaceful break from the city, but even more so at night.”

Our social place also influences levels of our exposure to harmful or dangerous elements in the environment. As societies build solutions to harmful environmental issues our social place also influences our access to those solutions.

9.4.1 Inequality in Environmental Impact

Environmental inequality (also called environmental injustice) refers to the fact that low-income people and people of color are disproportionately likely to experience the impacts of environmental problems (Bullard & Johnson 2009; Mascarenhas 2009). Inequality in environmental impact refers to the unequal impacts felt by environmental issues. To study this inequality, we can ask: Which groups experience the impacts of environmental issues more than others? What are those impacts?

While human decision making can harm the environment and therefore cause detriment to the human experience, human decisions made by people in power can also harm those with less access to resources. Sociologists McCarthy and King (2009) cite several environmental accidents that stemmed from reckless decision making and natural disasters in which human decisions accelerated the harm that occurred.

9.4.1.1 Man made disasters

One accident, the result of reckless decision making occurred in Bhopal, India, in 1984, when a Union Carbide pesticide plant leaked 40 tons of deadly gas. Between 3,000 and 16,000 people died immediately and another half million suffered permanent illnesses or injuries. A contributing factor for the leak was Union Carbide’s decision to save money by violating safety standards in the construction and management of the plant.

Most who died were the poorest members of Bhopal, living in settlements near the factory (Broughton 2005 and Agarwal 2022). Because of the resulting health issues survivors experienced, the gas leak entrenched their poverty and marginalization for following generations (Anon. 2014) (figure 9.28).

Figure 9.28. In Bhopal, thirty-four years after the leak, survivors groups come together to march in what has become a yearly torchlight rally. They demand justice and compensation for the loss of loved ones and their ongoing health issues.

Hurricane Katrina was another environmental and social disaster in which human decision making resulted in a great deal of preventable damage (figure 9.29 and 9.30). After Katrina hit the Gulf Coast and especially New Orleans in August 2005, the resulting wind and flooding killed more than 1,800 people and left more than 700,000 homeless. McCarthy and King (2009: 4) attribute much of this damage to human decision making: “While hurricanes are typically considered ‘natural disasters,’ Katrina’s extreme consequences must be considered the result of social and political failures.”

Long before Katrina hit, it was well known that a major flood could easily breach New Orleans levees and have a devastating impact. Despite this knowledge, U.S., state, and local officials did nothing over the years to strengthen or rebuild the levees. In addition, coastal land that would have protected New Orleans had been lost over time to commercial and residential development.

Figure 9.29. Hurricane Katrina as it approached New Orleans.

Figure 9.30. FEMA Urban Search and Rescue Task Force members and local rescue workers and US Coast Guard, search for residents in neighborhoods impacted by Hurricane Katrina.

According to sociologist Nicole Youngman (2009:176), this development also “placed many more people and structures in harm’s way than had existed there during previous hurricanes.” All these factors led Youngman to conclude that Katrina’s impact “demonstrated how a myriad of human and nonhuman factors can come together to produce a profoundly traumatic event.” In short, the flooding after Katrina was a human disaster, not a natural disaster.

9.4.1.2 Hazardous living conditions

Outside of natural disasters, neighborhoods populated primarily by people of color and members of low socioeconomic groups are burdened with a disproportionate number of hazards, including toxic waste facilities, garbage dumps, and other sources of environmental pollution and foul odors that lower the quality of life.

Figure 9.31. A burning site for the recovery of copper from electronics waste in Agbogblosh, Accra, Ghana. Agbogblosh is a settlement where war refugees and unemployed residents turn to scrap metal collection, including auto scrap, to supplement incomes. This method of waste processing emits toxic chemicals into the air, land and water. Exposure is especially hazardous to children, as these toxins are known to inhibit the development of the reproductive system, the nervous system, and especially the brain.

All around the globe, members of minority groups bear a greater burden of the health problems that result from higher exposure to waste and pollution (figure 9.30). This can occur due to unsafe or unhealthy work conditions where no regulations exist (or they are not enforced) for poor workers, or in neighborhoods that are uncomfortably close to toxic materials.

Research shows that in the U.S., for many African Americans, these inequalities pervade all aspects of their lives. Examples include environmentally unsound housing, schools with asbestos problems, or facilities and playgrounds with lead paint. A twenty-year comparative study led by sociologist Robert Bullard determined “race to be more important than socioeconomic status in predicting the location of the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities” (Bullard et al. 2007). His research found, for example, that Black children are five times more likely to have lead poisoning (the leading environmental health threat for children) than their White counterparts, and that a disproportionate number of people of color reside in areas with hazardous waste facilities (Bullard et al. 2007).

9.4.1.3 Environmental Racism

Many of these inequalities are related to racism. Racism is the process by which systems and policies, actions and attitudes create inequitable opportunities and outcomes for people based on race. Racism is more than just prejudice in thought or action. It occurs when this prejudice – whether individual or institutional – is accompanied by the power to discriminate against, oppress or limit the rights of others (What Is Racism?).

For example, Danielle Vermeer outlines one obvious connection between racism and environ- mental inequality:

Homeownership has been a core value and aspiration for many American households over the last half century. However, beneath this ideal, there is a legacy of racist housing policies that left low-income individuals and people of color disproportionately exposed to the impacts of environmental burdens. (Vermeer 2021)

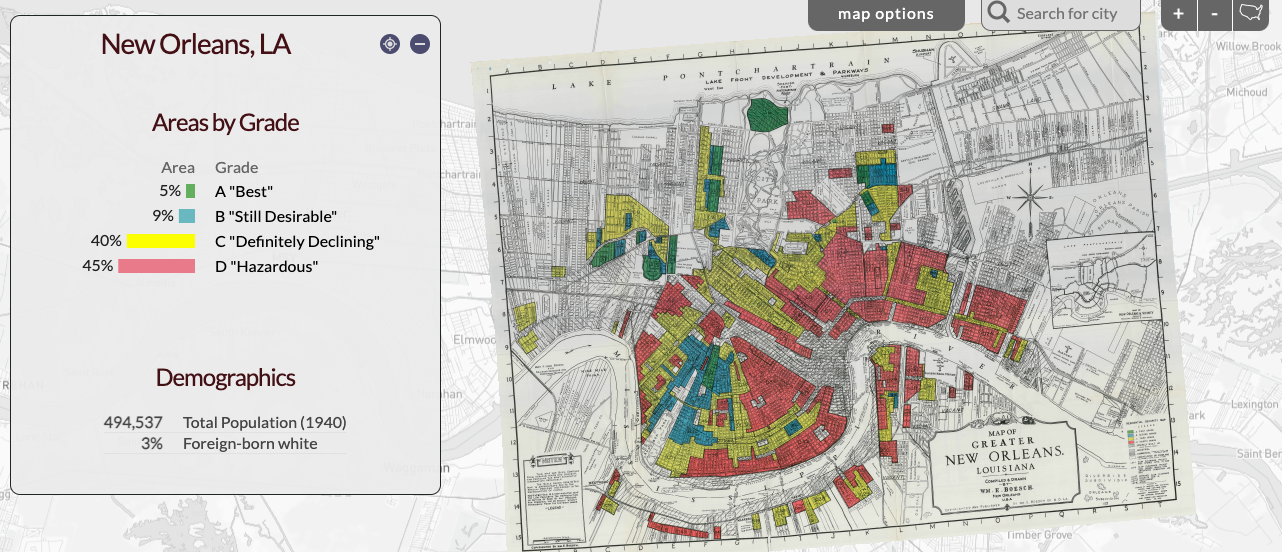

Vermeer refers to the practice of redlining, which was a discriminatory housing practice that arose during the Depression era. Real estate professionals—lenders, developers, and real estate appraisers would outline areas with larger Black populations in red ink on maps as a warning to mortgage lenders. This significantly contributed to segregating Black people in areas that would incur lower levels of economic investment and government support than White neighborhoods.

Figure 9.32 shows a redlined map of New Orleans. Click on the image to view this map in the Mapping Inequality website. Then, hover over and scroll within the box on the left to see how neighborhoods were graded.

Figure 9.32 an example of a redlined map of New Orleans, Louisiana from the Mapping Inequality website.

While redlining was outlawed in the 1960s discrimination against people of color buying homes in White neighborhoods continued. This discrimination and the legacy of redlining has reinforced unjust living conditions for minority residents nationwide. A report conducted in 2021 by the real estate firm Redfin found that “… formerly redlined neighborhoods have a larger share of homes endangered by flooding than neighborhoods that weren’t targeted by the racist 1930s housing policy.” (Katz 2021).

In the case of flooding in New Orleans, the Scientific American reports that “four of the seven zip codes that suffered the worst flood damage from Katrina had Black populations of at least 75%.” (Thomas 2020). Sociologists Jean Ait Belkhir and Christiane Charlemaine adds that shed light on some details:

- People with lower income and people of color lived in the flood prone areas of New Orleans. There existed no real protection for them as the city had inadequate dikes, levees and evacuation plan for such an emergency. Funding for the levees had been diverted to the war on Iraq, and the Louisiana Guard had been deployed to Baghadad.

- Once the hurricane hit, the federal government was slow to respond. When it did, the saving of property was prioritized over the saving of people, and many people of color who were caught up in the evacuation decried the treatment they received…

- Those not living in poverty were able to escape with vehicles. They had access to credit cards and bank accounts to stay in hotels or get supplies. In the aftermath they were also more likely to have insurance policies to recover and rebuild.

(Belkhir and Charlemaine 2007)

In short, “…exposure to the hurricane’s devastation was a function of place, race, gender and class.” (Belkhir and Charlemaine: 121).

9.4.1.4 Native American Tribes and Environmental RacismNative Americans are unquestionably victims of environmental racism. The Commission for Racial Justice found that about 50 percent of all Native Americans live in communities with uncontrolled hazardous waste sites (Asian Pacific Environmental Network 2002). There’s no question that, worldwide, indigenous populations are suffering from similar fates. For Native American tribes, the issues can be complicated—and their solutions hard to attain—because of the complicated governmental issues arising from a history of institutionalized disenfranchisement. Unlike other racial minorities in the United States, Native American tribes are sovereign nations. However, much of their land is held in “trust,” meaning that “the federal government holds title to the land in trust on behalf of the tribe” (Bureau of Indian Affairs 2012). Some instances of environmental damage arise from this crossover, where the U.S. government’s title has meant it acts without approval of the tribal government. Other significant contributors to environmental racism as experienced by tribes are forcible removal and burdensome red tape to receive the same reparation benefits afforded to non-Indians. To better understand how this happens, let’s consider a few example cases. The home of the Skull Valley Band of Goshute Indians was targeted as the site for a high-level nuclear waste dumping ground, amid allegations of a payoff of as high as $200 million (Kamps 2001). Keith Lewis, an indigenous advocate for Native American rights, commented on this buyout, after his people endured decades of uranium contamination, saying that “there is nothing moral about tempting a starving man with money” (Kamps 2001). In another example, the Western Shoshone’s Yucca Mountain area has been pursued by mining companies for its rich uranium stores, a threat that adds to the existing radiation exposure this area suffers from U.S. and British nuclear bomb testing (Environmental Justice Case Studies 2004). In the “four corners” area where Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico meet, a group of Hopi and Navajo families have been forcibly removed from their homes so the land could be mined by the Peabody Mining Company for coal valued at $10 billion (American Indian Cultural Support 2006). Years of uranium mining on the lands of the Navajo of New Mexico have led to serious health consequences, and reparations have been difficult to secure; in addition to the loss of life, people’s homes and other facilities have been contaminated (Frosch 2009).

Figures 9.33 and 9.34. Two of the many paintings by Chip Thomas, of the Navajo Nation. Chip is a physician in northeast Arizona but better known for his artwork on sheds, homes, and water towers on tribal lands such as this settlement: Cameron, in Coconino County, Arizona. Figure 9.33 reads “Are they not waging nuclear war when miners die from cancer from mining the uranium.” In yet another case, members of the Chippewa near White Pine, Michigan, were unable to stop the transport of hazardous sulfuric acid across reservation lands, but their activism helped bring an end to the mining project that used the acid (Environmental Justice Case Studies 2004). These examples are only a few of the hundreds of incidents that Native American tribes have faced and continue to battle against. Sadly, the mistreatment of the land’s original inhabitants continues via this institution of environmental racism. How might the work of sociologists help draw attention to—and eventually mitigate—this social problem? |

Watch this 5-minute video “How climate change is making inequality worse”. As you do, take note of the inequalities associated with climate changes presented.

Figure. 9.35. “How climate change is making inequality worse [Youtube Video]”

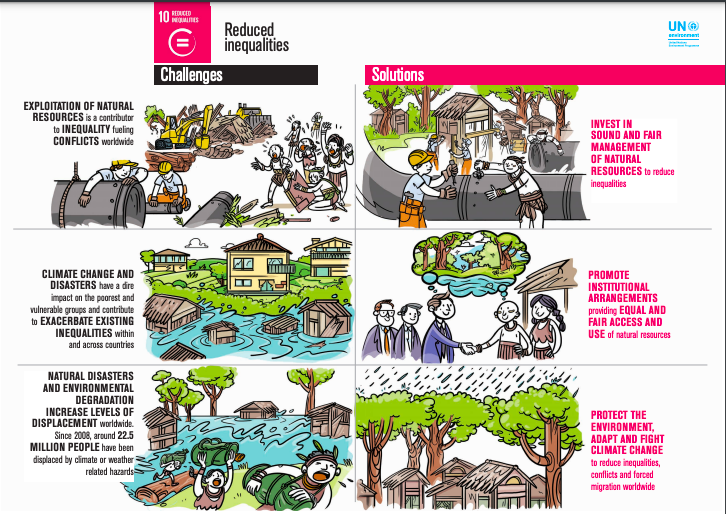

Taking a global view, we can peek into the work of the United Nations and the Sustainability Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries. The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) focuses their work on Goal 10 with projects that reduce inequalities related to the environment. They include addressing the following concerns:

- The exploitation of natural resources as a contributor to inequality and conflicts. Solutions include investing in sound and fair management of natural resources.

- Climate change and disasters that impact the poorest and vulnerable groups and exacerbate existing inequalities within and across countries

- Natural disasters and environmental degradation that increase levels of displacement worldwide.

See figure 9.35 for a snapshot of the challenges they see. Also, take a look at solutions they are working on at the UNEP.

Figure 9.36 “Reduced Inequalities” infographic by the United Nations Environmental Program.

9.4.2 Environmental Impacts, COVID-19 and Inequality

Consider what we’ve discussed about social place and our varied experiences with environmental change. What impact has the pandemic, as an environmental issue, had on individuals in society, based on race, ethnicity, and gender?

The New York Times article, “Virus is Twice as Deadly for Black and Latino People Than Whites in NYC” reports that in 2020 the coronavirus was killing black and Latino people in New York City at twice the rate that it was killing white people. The Mayor of New York City reflected that this disparity matches the standard economic inequalities and differences in access to health care:

There are clear inequalities, clear disparities in how this disease is affecting the people of our city,” Mr. de Blasio said. “The truth is that in so many ways the negative effects of coronavirus — the pain it’s causing, the death it’s causing — tracks with other profound health care disparities that we have seen for years and decades. (Mays and Newman 2020)

Racism in health systems alongside segregated health services, xenophobia against people from China and other parts of East Asia, and severe lack of data of the impacts of the disease among Native Americans are a few issues that the pandemic has revealed.

9.4.3 Inequity in Environmental transition

Inequity in environmental transition refers to uneven investment in environmental solutions based on social place. That is, based on our social place, we receive different access to environmental solutions and we receive different protections from environmental issues.

Many policies and initiatives established as solutions to environmental issues ignore or harm people of color or women. For example, environmental policies such as expansions of public transport, carbon pricing, and taxes, affect women and poorer households negatively because these policies often overlook their needs.

For example, a public policy transit route might serve the 9-to-5 commuter but ignore the needs of mothers who need to arrange to get their kids to school. Or, taxes might increase the prices of goods on which lower income families rely. In one scenario, environmentally friendly cooking stoves were discontinued from a program when organizers realized their impact on emissions was smaller than initially expected. However, the stoves had improved women’s and children’s health and safety (Gloor et al. 2022) (figure 9.36).

Figure 9.37. Energy efficient stoves being used with both charcoal and firewood in Lobule Refugee Settlement, West Nile Uganda

Figure 9.38. A person in Rwanda cooks with an improved cooking stove designed to reduce pressure on forest resources.

The Luskin Center for Innovation at The University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) provides some more examples of how the designers of environmental solutions can ignore inequality and equity.

- Energy technologies, such as rooftop solar panels, are typically first adopted by affluent households. Yet those with the least income could benefit most from lower energy bills associated with energy efficiency retrofits, demand response programs, and rooftop solar.

- California is the only state in the U.S. to legally recognize a Human Right to Water. However, this right is not yet a reality in all communities, particularly in disadvantaged areas that receive water from private wells and small community water systems with limited capacities.

(UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation 2023)

Figure 9.39. Water has been a challenge for years in the San Joaquin Valley, California. A photo by Dorothea Lang documents water supply at American River camp in 1936. Migrant workers’ children are assigned to pull water from the pump.

Figure 9.40. Vue Her is a Hmong farmer on a 10-acre field in Singer, CA, San Joaquin Valley, California November, 2018. Water is still crucial for this agricultural area but they have experienced the water table dropping over the past 14 years, preventing them from digging wells. (Sacher 2021)

In 2021 nearly a million Californians lived with unsafe drinking water from a failing water system; more than two‑thirds of these were located in communities with significant financial need (Tilden 2022).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change outlines three principles important in attaining equity in our environmental solutions:

- Distributive justice – striving for an equitable allocation of the burdens and benefits of solutions among individuals, nations and generations.

- Procedural justice – paying attention to who participates in decision-making about environmental solutions.

- Recognition- having respect for, engagement with, and fair consideration of diverse cultures and perspectives.”

(IPCC 2022)

There are many thinkers and organizations working on ways that equity in environmental transition can be improved. This collective goal is often called Just Transition. For a good example, watch this 4:10-minute video, “Oakland 2030: Equity at the Center” by Marybelle N. Tobias. Marybelle is the founder and principal of Environmental Justice Solutions, a Bay Area EJ consulting firm helping the City of Oakland make equitable decisions for their 2030 Equitable Climate Action Plan.

Figure 9.41. “Oakland 2030: Equity at the Center [Youtube Video]”.

Consider what Marybelle N. Tobias shared regarding the just transition she encourages for Oakland. If you were to plan a just transition plan for your city or region, what would you include?

9.4.3.1 Going Deeper

- For more information on redlining, see the web page: Mapping InequalityRedlining in New Deal America

- For a strong story on Xenophobia in the time of COVID-19, please listen to the 25 minute podcast by NPR: When Xenophobia Spreads Like a Virus.

- Browse through the COVID-19 Racial Equity and Social Justice Resources page at Racial Equity Tools for a very good overview of issues related to COVID-19 and inequity.

9.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for Environmental Inequality and Inequity

“Society and the Environment” is a remix of Chapter 20.4 “Understanding the Environment” in Sociology by University of Minnesota licensed under CC BY 4.0 and Chapter 20.3: “The Environment and Society” in Introduction to Sociology 3e”, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Several edits and additions made for context and updates. Several photos have been replaced or added, and the video, “What is the tragedy of the commons?” has been added. Concepts related to environmental racism and Hurricane Katrina were added and original text revised to better introduce racism within this text.

“Environmental Inequality and Inequity” is written by Aimee Samara Krouskop and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. It includes remixes from: Chapter 20.4 “Understanding the Environment” in Sociology by University of Minnesota licensed under CC BY 4.0, Chapter 20.3: “The Environment and Society” in Introduction to Sociology 3e”, licensed under CC BY 4.0, “Inequity in Impact” and “Inequality in Transition” found in Chapter 6.2 “Environmental Health” in “Environmental Biology” and licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.27. Photographer Rick Schwartz created this merged photo from images in Central Park, Manhattan, New York City. It is published on Flickr under (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Figure 9.28. In Bhopal, thirty-four years after the leak is provided by Bhopal Medical Appeal

and Rohit Jain. It is published on Flickr under (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Figure 9.29. Hurricane Katrina as it approached New Orleans is made available by U.S. NOAA, and published on Wikipedia Commons.

Figure 9.30. FEMA Urban Search and Rescue Task Force members is made available by Jocelyn Augustino / FEMA and published on Flickr under (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Figure 9.31. A burning site for the recovering of copper from electronics waste in Agbogblosh, Accra, Ghana is provided by Fairphone and published on Flickr under (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Figure 9.32 an example of a redlined map of New Orleans, Louisiana from the Mapping Inequality website is a snapshot from the same web site, published under CC BY 4.0.

Figures 9.33 and 9.34. Two of the many paintings by Chip Thomas, of the Navajo Nation. Both images are published by the Library of Congress here and here with no known restrictions.

Figure. 9.35. Video, “How climate change is making inequality worse” is published on YouTube.

Figure 9.36 “Reduced Inequalities” infographic by the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) is published on this page of the UNEP and used here under Fair Use.

Figure 9.37. A woman in Rwanda cooks with an improved cooking stove is made available by Rwanda Green Fund and is published on Flickr under (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Figure 9.38. Energy efficient stoves being used with both charcoal and firewood is provided by Laura Toledano and published on Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.39. Water has been a challenge for years in the San Joaquin Valley, California. A photo by Dorothea Lang is published with the Library of Congress with no known restrictions.

Figure 9.40. Vue Her is a Hmong farmer on a 10-acre field in Singer, CA, San Joaquin Valley, California is provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and published on Flickr under Public Domain.