2.3 Classical Sociological Perspectives on Social Change

Intersectionality can be considered a social perspective, or way of seeing the social world. At the heart of sociology is the sociological perspective, the view that our social backgrounds influence our attitudes, behavior, and opportunities in life. In this regard, we are not just individuals but rather social beings deeply enmeshed in society.

Does society totally determine our beliefs, behavior, and life chances? No. Individual differences still matter, and disciplines such as psychology are certainly needed for the most complete understanding of human action and beliefs. While all sociologists would probably accept the basic premise that social backgrounds affect people’s attitudes, behavior, and life chances, their views as sociologists differ in many other ways. Two main sociological perspectives that address social change are structural functionalism and conflict theory. Figure 2.20 summarizes the major assumptions of the functionalist and conflict approaches on social change.

|

Theoretical perspective |

Major assumptions |

|---|---|

|

Structural Functionalism |

Society is in a natural state of equilibrium. Gradual change is necessary and desirable and typically stems from such things as population growth, technological advances, and interaction with other societies that brings new ways of thinking and acting. However, sudden social change is undesirable because it disrupts this equilibrium. To prevent this from happening, other parts of society must make appropriate adjustments if one part of society sees too sudden a change. |

|

Conflict theory |

Because the status quo is characterized by social inequality and other problems, sudden social change in the form of protest or revolution is both desirable and necessary to reduce or eliminate social inequality and to address other social ills. |

Figure 2.20 Table of the major assumptions of Functionalism and Conflict Theory

2.3.1 Structural Functionalism

Structural Functionalism arose as early sociologists likened change in society to change in biological organisms. They said that societies evolved just as organisms do, from tiny, simple forms to much larger and more complex structures. They saw complexity increasing as societies become divided into social or occupational classes or differences in wealth, power, and control. When societies are small and less complex, there are few roles to perform, and just about everyone can perform all of these roles. As societies grow, many new roles develop, and not everyone has the time or skill to perform every role. People thus start to specialize their roles and a division of labor begins.

Several decades ago, Talcott Parsons (1966) presented an equilibrium model of social change. Parsons said that society is always in a natural state of equilibrium, defined as a state of equal balance among opposing forces. Gradual change is both necessary and desirable and typically stems from such things as population growth, technological advances, and interaction with other societies that brings new ways of thinking and acting. However, any sudden social change disrupts this equilibrium. To prevent this from happening, other parts of society must make appropriate adjustments if one part of society sees too sudden a change.

Functionalism has been heavily criticized within sociology. Some say it is framed with no or poor understanding of earlier societies and their deep complexities. Some argue there is a problem in assuming that everything that persists in society has a function for that society. For example, does poverty or discrimination really provide a function for society? Functionalism also has a hard time explaining inequalities including those related to race, gender, class, and at its worst, may help justify existing inequalities. Some critics argue that functionalists present a rather static view of society that fails to account for the realities of social change (figure 2.21).

For example, functionalist theory assumes that sudden social change is highly undesirable, when such change may in fact be needed to correct inequality and other deficiencies in the status quo. Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci, claimed that the functionalist perspective justifies the status quo in society and the underlying power dynamics that maintain that status quo. Finally, other critics say functionalism does not encourage people to take an active role in changing their social environment, even when doing so may benefit them.

Figure 2.21 A painting by Louis Maurice Boutet de Monvel, The Turmoil of Conflict (Joan of Arc series – IV), c. late 1909-early 1913. Critics of functionalism find that it presents a static view of society that fails to account for social change.

Figure 2.21 A painting by Louis Maurice Boutet de Monvel, The Turmoil of Conflict (Joan of Arc series – IV), c. late 1909-early 1913. Critics of functionalism find that it presents a static view of society that fails to account for social change.

2.3.2 Conflict Theory

First developed by Karl Marx in the 19th century, conflict theory claims that society is in a state of perpetual conflict because of competition for limited resources. Social order is maintained by domination and power, rather than by consensus and conformity. However, tensions and conflicts arise under two conditions. One, when resources, status, and power are unevenly distributed between groups in society. Two, when members of a society with less resources, status and power acknowledge that uneven distribution. These conflicts become the engine for social change.

Conflict theory arose in the United States in the 1960s and ’70s against the backdrop of the rise of various social movements in the United States. Rather than seeing institutions as benign, conflict theorists argue the institutions of a society promote the interests of the powerful, while subverting the interests of the powerless.

For example, consider how school funding is distributed. Schools in urban areas receive less financial support compared to their suburban counterparts. Those in suburban schools are given tools to get ahead, while those in urban schools are not (Kozol 1991). As a result the students that go to well funded schools have pathways into college and well paying jobs. For the students that attend schools with fewer resources they face barriers that can make it hard to get ahead.

Within the conflict perspective, social change is seen as emerging from people organizing and mobilizing together to pressure the institutions of the society. Change is not something that will emerge from within the institutions.

Critics of conflict theory argue that it exaggerates the extent of social inequality and overemphasizes social change. It is also seen as centering social class in the analysis of the social world, rather than other sources of oppression and privilege, such as race and gender.

2.3.3 Conflict Theory and Functionalism Compared

Whereas functionalism assumes the status quo is generally good and sudden social change is undesirable, conflict theory assumes the status quo generally results in unequal societies. It thus views sudden social change in the form of protest or revolution as both desirable and necessary to reduce or eliminate social inequality and to address other social ills.

In another difference between the two approaches, functionalist sociologists view social change as the result of certain natural forces. In this sense, social change is unplanned even though it happens anyway. Conflict theorists, however, recognize that social change often stems from efforts by social movements to bring about fundamental changes in the social, economic, and political systems. In this sense social change is more “planned,” or at least intended, than functional theory acknowledges.

2.3.4 Conflict Theory, Structural Functionalism, and Levels of Analysis

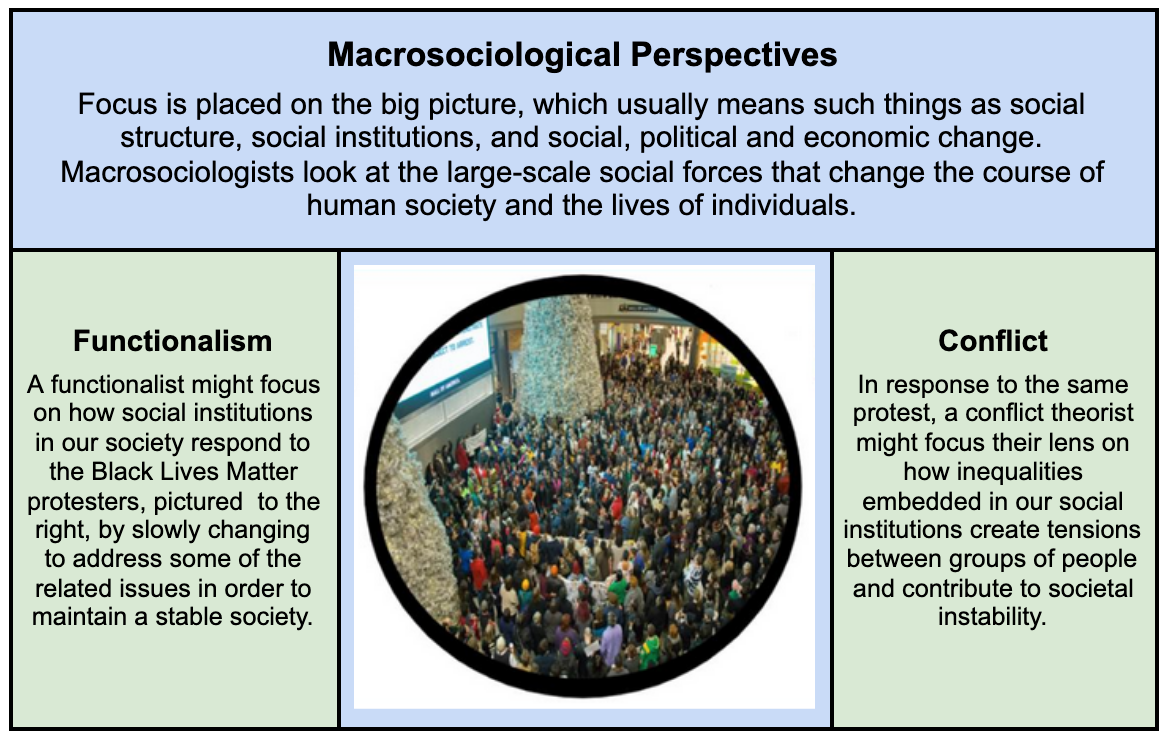

Both structural functionalism and conflict theory tend to focus on macro level, or large scale phenomena. For example a functionalist might focus on how social institutions in our society respond to the Black Lives Matter protests by slowly changing to address some of the related issues in order to maintain a stable society. Whereas a conflict theorist, in response to the same protest, might focus their lens on how inequalities embedded in our social institutions create tensions between groups of people and contribute to social instability (figure 2.22).

Figure 2.22. Table of Functionalism and Conflict Theory perspectives in the context of macrosociology

2.3.5 Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic Interactionists are concerned with how meanings are constructed through interactions with others. We attach meanings to situations, roles, relationships, and things whenever we encounter them. For a symbolic interaction to occur, these meanings have to be shared and agreed upon by the people you are interacting with. As we develop shared meaning we also develop common rituals and shared values.

For example, if we attach the meaning of “family member” to someone, we will treat them as a family member (or act on the basis of the meaning of family member) as we go about interacting with them. We share common rituals such as holiday celebrations. We share common values such as kindness and loyalty. What we define as family originates from interactions with others, such as parents, siblings, teachers, the media and elsewhere.

2.3.5.1 Critique of Symbolic Interactionism

Applied to social change, critics argue that symbolic interactionism tends to downplay power, privilege, and oppression. Some present day interactionists have tried to correct these problems by showing how symbolic interactionism can be used to explain power (Athens 2010) and organizational patterns (Hallett and Ventresca 2006).

Instead of viewing common rituals and shared values as integrating people into the society, conflict theorists argue these values and rituals are actually ideologies that deceive people and make people comfortable with their position in society.

One dominant ideology within the United States that is heavily criticized by conflict theorists is the idea of the “American Dream,” where you work hard and get ahead. Conflict theorists argue that the opportunities to get ahead for most people are severely curtailed due to artificial barriers in most institutions. The American Dream ideology, according to conflict theorists, justifies the position of those already at the top of the power structure (Colomy 2010).

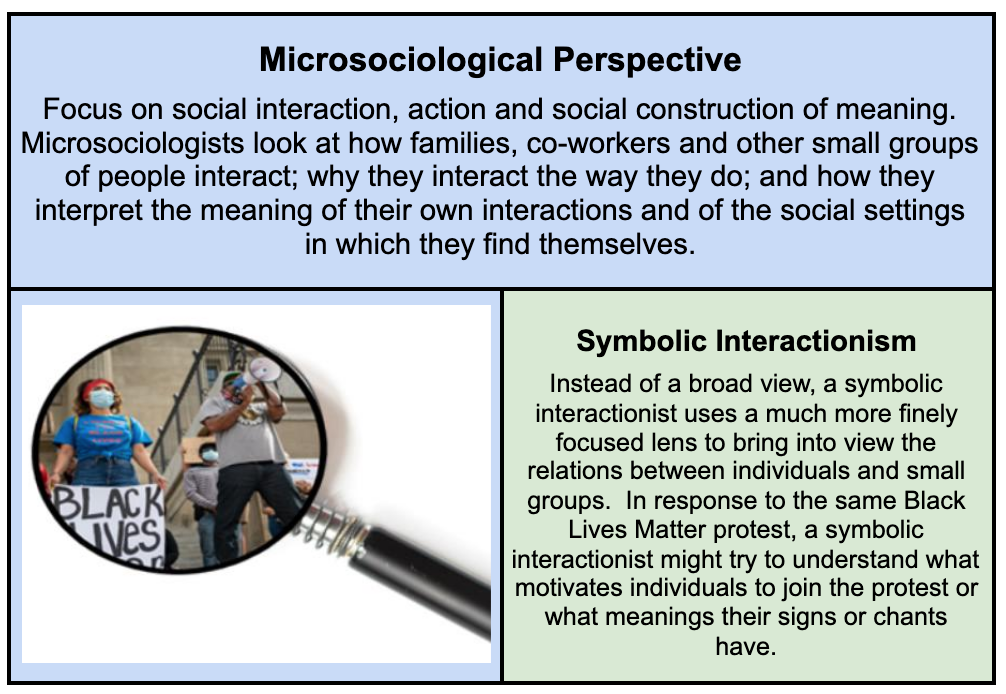

2.3.6 Symbolic Interactionism and Levels of Analysis

Symbolic interactionism provides a micro, or smaller scale theory to understand society. Instead of a broad view, a symbolic interactionist uses a much more finely focused lens to bring into view the relations between individuals and small groups. In response to a Black Lives Matter protest, a symbolic interactionist might try to understand what motivates individuals to join the protest or what meanings their signs or chants have (figure 2.23).

Figure 2.23: Table of the Symbolic Interactionism perspective in the context of macrosociology

2.3.7 Licenses and Attributions for Classical Sociological Perspectives on Social Change

“Classical Sociological Perspectives on Social Change” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0, with the exception of:

“Classical Sociological Perspectives on Social Change first two paragraphs” is adapted from “1.1 The Sociological Perspective”,no author provided, in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA,

Figure 2.20 is adapted from the Theory Snapshot table in “Sociological Perspectives on Social Change”, “20.1 Understanding Social Change” in Sociology by University of Minnesota, licensed under CC4.0

“Structural Functionalism” is a remix of “20.5 End of Chapter Material, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA, and 2.5 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Photo updated and content edited for context.

Figure 2.21 A painting by Louis Maurice Boutet de Monvel, The Turmoil of Conflict (Joan of Arc series – IV), c. late 1909-early 1913.

“Conflict Theory” is a remix of “20.5 End of Chapter Material, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA, and and “2.5 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Conflict Theory and Functionalism Compared”, “Symbolic Interactionism”, Postcolonial Theory”, and “Feminist Theory” are remixes of “2.5 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Conflict Theory, Structural Functionalism, and Levels of Analysis” and “Symbolic Interactionism and Levels of Analysis” are remixes of“1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology”, “Macro and Micro Approaches”, by Jean M. Ramierez; Suzanne Latham; Rudy G. Hernandez; and Alicia E. Juskewycz in Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.22. Table of Functionalism and Conflict Theory perspectives in the context of macrosociology is found in “1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology”, “Macro and Micro Approaches”, by Jean M. Ramierez; Suzanne Latham; Rudy G. Hernandez; and Alicia E. Juskewycz in Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.23 Table of the Symbolic Interactionism perspective in the context of macrosociology is found in “1.3 Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology”, “Macro and Micro Approaches”, by Jean M. Ramierez; Suzanne Latham; Rudy G. Hernandez; and Alicia E. Juskewycz in Exploring Our Social World: The Story of Us, licensed under CC BY 4.0.