5.4 How Economic Systems Change

As we’ve seen, economic systems change over time. But what causes that change? There are certainly many answers to this question. We’ll explore two: technological change and class conflict.

5.4.1 Technology

The development of new technologies can transform an economy, altering not only the methods of production but also the human relationships and dynamics of power. Famously, industrial production was transformed in the early 20th century with the development of the assembly line.

First implemented in Ford’s car assembly plants, the assembly line increased economic efficiency by breaking the production process down to a series of small actions performed repetitively by workers. A single worker might spend 10 hours performing the same task as one car after another moves down the line in front of them, as shown in figure 5.5.

Figure 5.5 “Workers on the first moving assembly line put together magnetos and flywheels for 1913 Ford autos” Highland Park, Michigan

This new production system produced more vehicles per “man-hour,” meaning that a given number of workers could produce more cars in a single day. It also made labor increasingly monotonous (and often dangerous) for workers. So, this new technology of production, the assembly line, created new efficiencies as well as new forms of labor and relations of power. And since these efficiencies increased the profits, business leaders implemented the assembly line in all kinds of industries, from fast food to fast fashion.

More recently, the development of massive data collection has enabled new economic opportunities and relationships of power. Harvard Professor Shoshana Zuboff argues in her book Surveillance Capitalism (2019), that the rise of big data marks a shift in the economy akin to the development of the assembly line. Entirely new markets have emerged which use surveillance data collected by various apps and websites to predict consumer behavior. For example, social media algorithms on sites like Facebook determine which ads they will show you. Zuboff warns that “surveillance capitalism” threatens to undermine our ability to function as a democratic society. Technological changes in the economy often come “from above.” In other words, economic elites develop and implement new technologies to serve their interests. However, there are also significant ways in which economies can be changed “from below.”

5.4.2 Going Deeper

Check out this excellent interview with Shoshana Zuboff, “High Tech Is Watching You” conducted by John Laidler (2019) published in the Harvard Gazette (about a ten minute read).

Consider these questions:

- How does surveillance and data enable new profits?

- How does surveillance and data create new forms of power?

5.4.3 Organized Labor

Throughout the history of capitalism, the lower classes have consistently resisted economic arrangements they see as exploitative. Over the past century in the United States, workers have successfully redefined the economy in profound ways, from fighting for the 8-hour day and 40-hour week to pushing for worker oriented legislation, like worker safety rules, minimum wage laws, and social security. Today, many workers are fighting to retain these past gains and pushing for things like increased wages, predictable schedules and healthcare benefits. Check out this 9-minute video in figure 5.6 about the work experiences of many retail and food service workers.

Ask yourself, how do “flexible schedules” impact different groups differently: workers, owners, and consumers?

5.4.3.1 The fight to make bad jobs better

Figure 5.6. Vox: The Fight to Make Bad Jobs Better [YouTube Video]

How do workers, who appear to have little power within a workplace, successfully push for higher wages, benefits, and improved working conditions? Probably the clearest answer is through organizing collectively within a union.

A union is an organization of workers who work together to improve their wages and working conditions. Workers and business owners typically have competing interests. Business owners have an interest in maintaining a low cost of production, in order to maximize profits. That means that for the business owner, it is usually ideal to keep wages as low as possible and working conditions under their discretion. However, workers usually have an interest in increasing their wages and establishing working conditions that maintain their safety at work and quality of life outside of work. In the current service industry, for example, workers often want higher wages and stable schedules, while owners often want lower wages and “flexible” schedules. So, as conflict theorists in sociology have often pointed out, there is a structural conflict between the interests of workers and owners within capitalism.

If the interests of workers and owners are structurally opposed, how do workers achieve their goals, against the interests of their bosses?

Since owners rely on the labor of workers, workers can pressure owners by threatening to collectively refuse to work. This is called a strike. A strike is a form of collective action when workers in a given workplace refuse to work until owners meet their demands (figure 5.7).

Figure 5.7. Untitled UAW Local 174 Mural by Walter Speck, depicting the 1937 auto workers strike in Flint Michigan.

Over the past century, the relative power of the labor movement has significantly impacted workers wages and working conditions. Workers in unions usually earn higher wages than non-unionized workers. But a high level of union membership can even lead to higher wages for non-unionized workers, since they lift the overall wages of a labor market. Partly for these reasons, periods of high union membership (like the 1940s-–1970s) are associated with higher wages for most workers, while periods of lower union membership (like the late 1970s–the present) have seen declines in wages for most workers, when adjusted for inflation. As seen in Figure 5.8 below, union membership has been declining since 1970 while the income share of the top 1% and top 10% have increased.

Figure 5.8. This graph from the Center for Economic Policy Research shows declining union membership is correlated with increasing income share for high income earners.

Currently, workers around the United States have been increasingly organizing, winning union representation at companies like Starbucks and Amazon. Whether the labor movement will reverse the trend of declining real wages remains to be seen.

5.4.3.2 May Day: A labor movement case study

Although most Americans don’t remember it, 1886 is arguably the most revolutionary year in U.S. history (Brecher 1997). American workers were facing a new form of labor—industrial wage labor—and many of them saw it as un-American. Many even referred to it as wage slavery. Work days were long and dangerous, and low wages left most workers in poverty.

Some of the more radical organizers within the labor movement called for a general strike on May 1, 1886, to demand the eight-hour workday. A general strike is a strike of all workers within a society, not just the workers at one workplace or in one industry. It is perhaps the most powerful tool available to the working class (Brecher 1997).

When May 1, 1886 arrived, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike across the country. The 8-hour day movement was especially concentrated in Chicago, where tens of thousands of strikers marched through the street, calling on their fellow workers to set down their tools, walk off the job, and join the strike. The city’s ruling class prepared for the strike by deputizing and arming thousands of men to put down the strike effort.

On May 4, anarchist organizers held a rally in Haymarket Square to protest the violent death of workers the previous day. Anarchism–a popular current within the labor movement at that time–is a political philosophy advocating for the elimination of all or most forms of hierarchy including the abolition of the state.

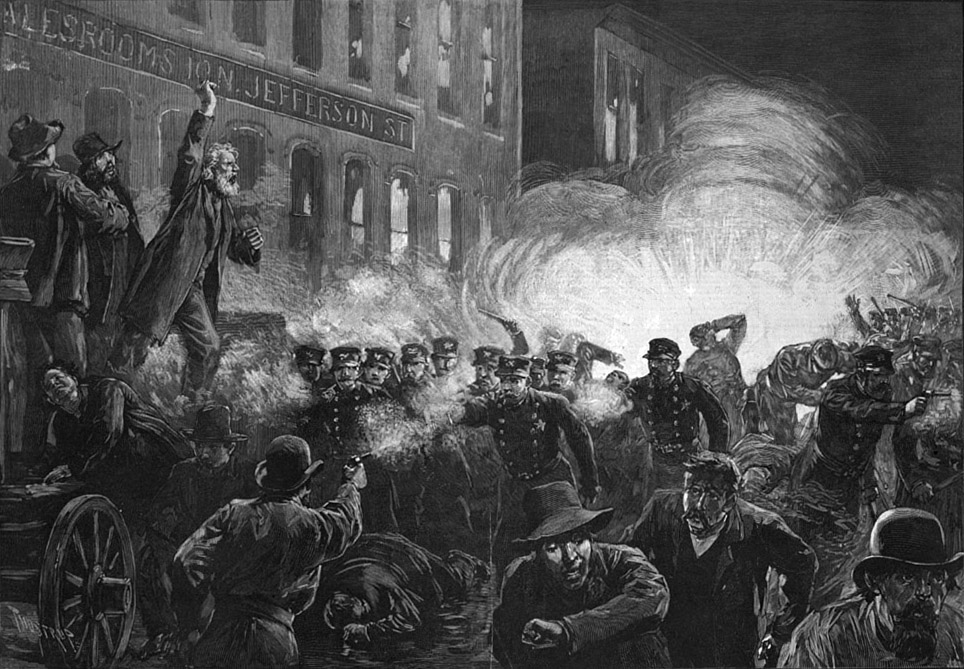

The details of the events that followed are disputed by historians, but it is clear that after police began to push workers out of the square, someone threw a bomb toward the police, which exploded, resulting in the deaths of seven police officers. The police then began shooting into the crowd of workers, killing at least four people (figure 5.9).

Figure 5.9. This popular engraving shows Methodist Pastor and anarchist Samuel Fielding speaking at the Haymarket Rally as a bomb detonates among the police ranks and police open fire into the crowd.

It is important to note that anarchism is not inherently related to violent protest. Like with all political philosophies, its followers vary. They include those who support violence in the face of unjust acts as well as those who reject all forms of violence. Many also fall in between (Anisin 2019). However the events at Haymarket Square–and the media reaction to it–resulted in a new stereotype of the bomb-throwing anarchist.

The Haymarket Massacre—as it has come to be known—provided a pretext for authorities to criminalize the labor movement across the country. At least 50 union halls and worker hangouts were raided nationwide. In Chicago, eight prominent anarchist organizers were arrested on false charges of planning the bombing. Despite no evidence linking them to the bombing, four were hanged and one was violently killed while behind bars. The survivors were later pardoned by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, who stated that, “the judge [who ordered the hangings] conducted the trial with malicious ferocity” (Brecher 1997).

The eight-hour day campaign is commemorated around the world as “May Day”—International Workers Day (Linebaugh 2016). However most American workers don’t remember it. Why is that?

In 1894, President Grover Cleveland and conservative union leaders declared a federal “Labor Day” in September, effectively distancing the labor movement from the more radical tradition of May Day. In 1958, President Dwight Eisenhower declared May 1 “Law Day.” Over the years, May Day was largely forgotten by most American workers.

In the past two decades, however, May Day has begun to re-enter mainstream political consciousness in the U.S. This is the result of workers from outside the U.S., who have a tradition of celebrating May Day, migrating to the U.S. and bringing that tradition back home, so to speak.

Figure 5.10. Marchers at “A Day Without Immigrants” in Los Angeles, May Day 2006.

For example, on May 1, 2006, immigrant workers in the U.S. organized a general strike, dubbed “A Day Without Immigrants” (figure 5.10). Over a million people participated in immigrant rights protests across the country. In doing so, they reminded the broader American working class of a piece of its own history.

Memory matters. When workers lose the memory of past movements, such as the May 1st general strike, what else do they lose?

5.4.3.3 The labor movement today

Since 2019, workers in the U.S. have achieved several victories, organizing unions within some industries for the first time. Check out this 5:36-minute video (figure 5.11) which explores workers’ organizing efforts at Amazon. What challenges have they faced? How did they attempt to overcome them?

Figure 5.11. Inside Amazon Labor Union: How Workers Took On Amazon And WON [YouTube Video]

Workers at Starbucks have also achieved major gains in their organizing effort. In successfully organizing a union in their first Starbucks store in 2021, they accomplished something that many observers had seen as nearly impossible. As you watch the 8:20-minute video below (figure 5.12), consider the issues these workers face. Have you experienced similar issues in your own work life?

Figure 5.12. Why Starbucks Workers Fought to Unionize [YouTube Video]

5.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for How Economic Systems Change

“How Economies Change” by Ben Cushing is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.5 “Workers on the first moving assembly line put together magnetos and flywheels for 1913 Ford autos” Highland Park, Michigan

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ford_assembly_line_-_1913.jpg

Figure 5.6. Vox: The Fight to Make Bad Jobs Better https://youtu.be/a-4_6bThk2E

Figure 5.7. Untitled UAW Local 174 Mural by Walter Speck, depicting the 1937 auto workers strike in Flint Michigan. https://www.lawcha.org/2016/11/30/collection-spotlight-uaw-local-174-mural/attachment/3532 Used with Permission.

Figure 5.8. This graph from the Center for Economic Policy Research shows declining union membership is correlated with increasing income share for high income earners. https://cepr.net/union-membership-and-income-inequality/

Figure 5.9. Photo of engraving of Methodist Pastor and anarchist Samuel Fielding is published on Wikipedia under the Public Domain license.

Figure 5.10. Photo of marchers at “A Day Without Immigrants” in Los Angeles, May Day 2006 is by Jonathan McIntosh and published on Wikipedia under the CC BY 2.5 license.

Figure 5.11. Video, “Inside Amazon Labor Union: How Workers Took On Amazon and WON” is published on YouTube by More Perfect Union.

Figure 5.12. Video, “Why Starbucks Workers Fought to Unionize” is published on YouTube by

Bloomberg Quicktake: Originals.