2.2 How Sociologists Study Social Change

All sociologists are interested in the experiences of individuals and how those experiences are shaped by interactions with social groups and society. To a sociologist, the personal decisions an individual makes do not exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns, social forces, and influences put pressure on people to select one choice over another. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behavior of groups of people living in the same society and experiencing the same societal pressures.

For example, most Americans probably agree that we enjoy a great amount of freedom. And yet perhaps we have less freedom than we think, because many of our choices are influenced by our society in ways we do not even realize. Perhaps we are not as distinctively individualistic as we believe we are.

Figure 2.4: Photo of Woman Holding Elevator Door

Think back to the last time you rode in an elevator. Why did you not face the back? Why did you not sit on the floor? Why did you not start singing? Children can do these things and “get away with it,” because they look cute doing so, but adults risk looking odd. Because of that, even though we are “allowed” to act strangely in an elevator, we do not (figure 2.4).

We also know that, even though we’ve learned how to ride an elevator a certain way, we are susceptible to the actions of others. Watch this 2:14-minute video, “Elevator psychology – Social Influence” (figure 2.5). It’s a clip from the 1960s-era television program, Candid Camera. As you watch, imagine why the Candid Camera “stars” (the ones not aware of the experiment) follow the action of the other elevator passengers.

Figure 2.5 Elevator psychology – Social Influence [Vimeo Video]

Understanding how social influences affect human behavior is the basis for understanding how society changes. Sociologists examine the behavior of groups in a few ways. First, they use certain tools of thought that frame their thinking about society. Second, they break down society into components to better understand how society operates. We’ll refer to those components here as building blocks. Third, they see certain elements of society as foundations. There is some varied interpretation of the building blocks of society among sociologists, but what matters is that we consider these structures as influencers of human behavior.

2.2.1 Tools of Sociology

There are many ways that one can approach sociology and understand our fascinating social behaviors – be they in an elevator or on the soccer field. However, most sociologists agree on a set of basic tools. Consider them the frameworks for understanding society and its members.

2.2.1.1 Sociological Imagination

Figure 2.6 Photo of C. Wright Mills. Image by Gambar Fritz Goro

Figure 2.7.Photo of C. Wright Mills. Image by Yaroslava Mills and (c) Nik Mills.

C. Wright Mills (figures 2.6 and 2.7) coined the term sociological imagination, an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior and experience and the wider culture that shaped the person’s choices and perceptions. Said another way, sociological imagination is ”… the ability to look beyond the individual as the cause for success and failure and see the society in which one lives as the cause” (Mills 1959). This framework helps us examine how people’s experiences differ according to their place in society and the limitations and opportunities they experience as a result.

Watch the 2:28-minute film “The Sociological Imagination” (figure 2.8). As you do, consider: “In what ways are you already using your sociological imagination?”

Figure 2.8 The Sociological Imagination [YouTube Video]

The sociological imagination allows us to make connections between your – and others’- personal experiences and the broader forces that impact us. Those forces may be economic, political, cultural, familial, educational or environmental. They each influence the world that we see, the opportunities that are available to us, and the challenges we face.

2.2.1.2 Social Construction of Reality

The social construction of reality has become another very common framework for understanding society. When we explain as sociologists that something is socially constructed, we mean that as members of society, we give meaning and value to behavior, ideas, or objects. This process is ongoing and happens through our everyday social interactions.

By creating meaning and value to ideas or objects or actions this way, we make sense of the world, convey this understanding to others, and find ways of sharing those understandings. In turn, we can observe the consequences (positive, negative, or neutral) of that social construction. Think of an American flag. People living in the United States, as well as outside of the U.S. hold various meanings attached to the flag. However, each of those meanings was created as a result of interactions with others.

2.2.1.2.1 The social construction of crimes

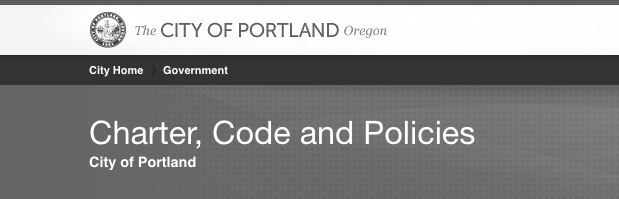

Another good way to see social construction is with crimes. How many of us stop to think about how the crimes we commit every day have come into being?…. You don’t commit crimes every day you say? A quick look here, at the “Charter, Code and Policies” page of the City of Portland might reveal a different story (also shown in figure 2.9). Among other regulations, it is a crime to cross a street other than within a crosswalk if within 150 feet of a crosswalk. It is also a criminal act as a pedestrian if you don’t cross a street at a right angle unless crossing within a crosswalk.

Figure 2.9 screenshot of the City of Portland’s web page, listing regulations related to pedestrian rules at crosswalks.

Figure 2.9 screenshot of the City of Portland’s web page, listing regulations related to pedestrian rules at crosswalks.

Portland is not unique in its pedestrian regulations. Many cities have similar codes and policies most are not aware of. Most Californians probably don’t know it’s illegal for a woman to drive wearing a bathrobe. And most residents of Sag Harbor, New York probably aren’t aware it is illegal to disrobe in your vehicle (Schubak 2018). There are untold examples of daily illegal acts most of us commit as we go about our day.

2.2.1.2.2 Social construction, inequity, and harm

When we apply a social construction lens to crime, recognizing that meaning has been created around our behaviors, it is easier to step back and think critically about how society is shaped. We can ask questions such as:

Who is deciding what behavior is a criminal act?

Who is determining which and how any of those laws on the books will be enforced?

Who determines which members of society violating those laws are pursued and punished?

These kinds of questions help us wrestle with the inequities in our society and begin to imagine ways that those realities may be changed. Today, the Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that “The most common reason for contact with the police is being a driver in a traffic stop”. Police traffic stops for trivial infractions such as broken tail lights or expired tags have come under great scrutiny. This is especially because too many of those stops are a pretext to search for drugs or guns.

Even more problematic, those stops correspond with racial, ethnic, and class profiling. Furthermore, too many stops for those kinds of violations result in harm or death of the driver (Kirkpatrick et al. 2022). In February 2022 a police officer fatally shot Mr. Daunte Wright in Minnesota, the same city where George Floyd was shot. Mr. Wright believed he had been pulled over because he had air fresheners hanging from his rearview mirror (The New York Times 2022).

While many of our laws related to criminal activity were implemented many decades ago, they are still a reflection of how we interact. Laws about the way we punish people for crimes also reflect historical and current structural inequality. In 2022, Oregon narrowly voted to strip language from its constitution that allows for slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime. Four states had similar initiatives on the ballot that year. The language goes back to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution’s 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery. Some states made exceptions to allow slavery as a punishment for a crime. As a result, Black Americans continued to be arrested under false pretenses after the Civil War, allowing slavery to continue (Bogel-Burroughs 2022 and Wilson 2022). Today, because the law allows for prisoners to be forced into labor for little or no pay, it is worth considering whether or not our system of slavery remains through that law.

2.2.1.2.3 Social construction and our identities

Finally, the social construction of reality can help us understand how we frame our identities. The way we think of ourselves and how we present ourselves to others is created and is constantly changing based on our interactions with others. According to Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley, we base our image on what we think other people see (Cooley 1902). We imagine how we must appear to others, then react to this speculation.

We wear certain clothes, prepare our hair in a particular manner, wear makeup, use cologne, and the like—all with the notion that our presentation of ourselves is going to affect how others perceive us. We expect a certain reaction, and, if lucky, we get the one we desire and feel good about it. But more than that, Cooley believed that our sense of self is based upon this idea: we imagine how we look to others, draw conclusions based on their reactions to us, and then we develop our personal sense of self. In other words, people’s reactions to us are like a mirror in which we are reflected.

Watch Jason Silva’s passionate discussion about the social construction of our identities in the 2:08-minute video, “Are We Who We Think We Are?” (figure 2.10). In what ways are you constructing your identity based on what you think others think of you?

Figure 2.10 Are We Who We Think We Are? [YouTube Video]

2.2.1.3 The Debunking Motif

Another key tool used to understand the foundations of society is the Debunking Motif. As Peter L. Berger (1963: 23–24) noted in his classic book Invitation to Sociology, “The first wisdom of sociology is this—things are not what they seem.” Social reality, he said, has “many layers of meaning,” and a goal of sociology is to help us discover these multiple meanings. He continued, “People who like to avoid shocking discoveries…should stay away from sociology.”

As Berger emphasized, sociology helps us see through conventional understandings of how society works. He referred to this theme of sociology as the debunking motif. By “looking for levels of reality other than those given in the official interpretations of society” (38), Berger said, sociology looks beyond on-the-surface understandings of social reality and helps us recognize the value of alternative understandings. In this manner, sociology often challenges conventional understandings of social reality and social institutions.

2.2.2 The Building Blocks of Society – Structure and Institutions

Studying social change with sociology also requires a focus on the basic components of society. Two main components are structure and institutions.

2.2.2.1 Structure

Structure, sometimes called social structure, refers to the complex and stable framework of society that influences all individuals or groups through the relationship between institutions (e.g., economy, politics, religion) and social practices (e.g., behaviors, norms, and values). These patterned arrangements both limit and create opportunities for individuals. Typically, more opportunities are available for people who share similarities with those in positions of power.

2.2.2.2 Institutions

Our social structure is made up of many institutions.Institutions or social institutions refer to a large-scale social arrangement that is stable and predictable, created and maintained to serve the needs of society. Examples of those institutions and related needs are in the list below:

- Government serves societies’ needs of establishing laws.

- Media serves societies’ needs for communication.

- Family serves societies’ needs of reproducing, raising children, and taking care of elders.

These arrangements reproduce themselves and show patterns across time and geography. Our institutions are often interconnected. For example, the economy, family, and education are separate social institutions that regularly intersect. Available work opportunities depend on the state of the economy and the access that individuals have to education. Our family arrangements and socioeconomic status may create or limit opportunities to pursue higher education.

Click through the Prezi presentation made by Elizabeth Berrios (figure 2.11) to learn more about some main institutions sociologists study: family, health and wellness, politics, economy, education, and religion. Clicking through each institution will also allow you to explore its functions.

Figure 2.11 Prezi Illustration of Social Institutions by Elizabeth Berrios

Social structures and institutions have rules and norms that are semi-durable. They tend to be consistent and somewhat stable. However, social institutions are made up of individuals which means that changes occur within institutions over time.

It’s important to distinguish sociology’s use of the term social institution, with the more common use of “institutes”. The word institutes refer to organizations, establishments, or foundations devoted to the promotion of a particular cause or program. Specific colleges and research centers are often called institutes.

2.2.3 Systems and Systems Thinking

Many institutions are systems of organizations built from economic, political, and other spheres of activity (Walzer 1983). For example, capitalism is one kind of economic institution that is made up of many forms of organizations. One of these forms is the multinational corporation.

In an increasingly complex and interconnected world, thinking about sets of institutions as systems can help us to understand, communicate, and address the challenges we face. Yet if you want to start using this approach, it can be difficult to know how to start.

2.2.3.1 Defining systems and systems thinking

Systems thinking is both an approach to seeing the world in a way that makes connections and relationships more visible and a set of methods and tools. Examining systems in this way improves our decision-making abilities. We encounter systems in many different contexts and situations—from circulatory systems to climate systems to healthcare systems to transportation systems. But what is a system? Why is it important to understand them?

A system is a group of two or more related parts that interact over time to form a whole that has a purpose, function, or behavior. We can conceive of systems as physical entities that we can observe and examine (like a tree or a subway system), or as abstract constructs we can use to understand our world (like a model of a cell or of the solar system). A system includes both individual parts, and also the relationships that hold the parts together—these can be physical flows (for example, the neural signals that allow us to sense our environment), or simply flows of information in a social system.

Many parts can form a whole, but unless they depend on and interact with each other, they are simply a collection. Consider a jar of dried basil, a jar of cinnamon, and a jar of paprika—a group of spices that comprise a spice rack. Their function does not change if you add or remove spice jars or re-arrange them, because the spice rack is simply a collection.

In contrast, your body is a system composed of multiple different, interacting, and interdependent organs or nested subsystems. A set of parts, arranged and connected, is essential for you to survive. Furthermore, these components can function together in ways that would not be possible for each part on its own, and as a system, exhibit properties that emerge only when parts interact with a wider whole (also known as emergent properties).

A good way to explore systems thinking is with an examination of the environment as a system. The environment is everything, all of the biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) parts of nature, of our world. The trees, the grass, the beetles, the bacteria, the water, the soil, the wind, even us humans… but is it just a jumbled collection of things? No, all those things are profoundly, intimately, and dynamically interconnected to each other, in ways that may be obvious or more subtle. If you change one part, the impacts of that change can ripple out throughout the system as a whole, in sometimes unexpected ways.

2.2.3.2 Systems thinking applied to public sector change

In 2018, the Scottish government applied a systems approach to determine how much progress had been made over the previous ten years with their goals to serve the public. The goals of government officials were to:

- create a more successful country

- give opportunities to all people living in Scotland

- increase the well-being of people living in Scotland

- create sustainable and inclusive growth

- reduce inequalities and give equal importance to economic, environmental, and social progress

(Scottish Government n.d. and Piret Tõnurist et al. 2020)

Figure 2.12 shows their model, based on systems thinking, that helped them visualize their goals.

Figure 2.12 Visualization of the National Performance Framework of the Scottish Government, a model based on systems thinking.

How do you see systems thinking in the National Performance Framework?

2.2.4 Foundations of Society – Culture, Social Facts, and Socialization

Other elements of society that influence our behavior are foundational to social life. These are cultural patterns, social facts, and socialization.

2.2.4.1 Culture

Culture refers to a group or society’s shared practices, values, beliefs, symbols, language, and artifacts. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from routine, everyday interactions to the most important parts of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society. Over the past century, American and European sociologists developed a wide variety of definitions of culture (Sewell 1999). At the broadest level, you could think of culture as “different ways of seeing and doing things” (Wray 2014: xix). Cultural sociology, a specific subfield within sociology, is focused on meaning making, with a particular focus on symbols, categories, and interpretation.

We introduced cultural universals in Chapter 1. They are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies. One example of a cultural universal is the family unit: every human society recognizes a kind of family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions varies.

In many Asian cultures, for example, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household, as shown in figure 2.13. In these cultures, young adults continue to live in the extended household family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household. Alternatively, they may remain and raise their nuclear family within the extended family’s homestead. In many communities in the U.S., by contrast, individuals are expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit that consists of parents and their offspring.

Figure 2.13 A Mongolian family in front of their ger (yurt) home

Cultural universals can also shift. For example, currently in some areas of the world, we are seeing a recognition of families that does not include reproduction or the care of children. They may be non-cisgendered couples, more than two adults living together as heads of a family, or cisgendered couples who have decided not to have children. Other cultural universals include customs like funeral rites, weddings, and celebrations of births. However, each culture may view and conduct the ceremonies quite differently.

2.2.4.2 Social facts

Some sociologists study social facts—the laws, morals, values, religious beliefs, customs, fashions, rituals, and cultural rules that govern social life. These practices exist outside of us as individuals. Instead, these rules act to constrain our behavior. Social facts make it possible to move beyond studying individuals so we can learn about the behavior of entire societies. Social theorist Émile Durkheim (1895) asserted that social facts are concrete ideas that influence the daily life of individuals. Durkheim discussed social facts within the context of kinship and marriage, language, and religion.

Another well-known example of Durkheim’s study of social facts is his examination of suicide rates. Using police suicide statistics from different districts, he found patterns in suicide rates that suggest suicide is not solely something that occurs at the level of the individual. He found there is a very strong link between people taking their own lives and social structure.

Durkheim proposed that suicide is related to our social integration: how well we know our place in society, and how well we experience a sense of belonging. The mythical Greek story of Ajax can serve as a reminder that suicide has been a fact of life for societies at least as long as history is able to tell. Ajax took his own life during a deep humiliation, after being passed over for promotion to lead the army by his fellow Greeks (figure 2.14).

Figure 2.14 Image of a vase, depicting the Greek Hero, Ajax, preparing for his suicide, by the painter Exekias, around 530 BC. The story is told that Ajax took his own life in an act of humiliation, for being passed over for promotion to lead the army by his fellow Greeks.

2.2.4.3 Socialization

In addition to social facts, sociologists look at socialization as a foundational element of society. Let’s return for a moment to the elevator example that we discussed earlier in the chapter. Looking at this behavior another way, we can say that through our interactions with others, we have been socialized to act in an elevator a certain way. Socialization is the lifelong process of an individual or group learning the expected norms and customs of a group or society through social interaction.

Socialization also affects how we identify. Think of the social influences that have informed how you identify, be it Latino or Hispanic, Filipino-American or Central Asian, African, African American or Black, cisgender, male, female, queer, or heterosexual.

2.2.4.4 The Institution of Family: social facts, socialization, and culture

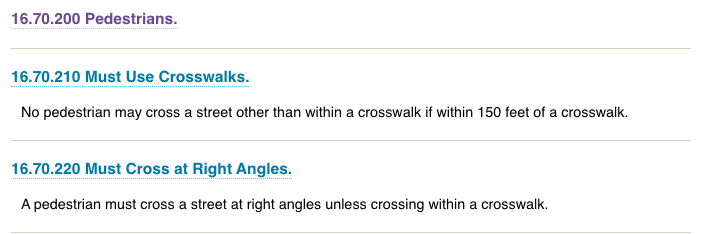

Figure 2.15 Image of Aboriginal Art, Wunnumurra Gorge

Let’s look closer at some of these parts of society through the institution of family. Sociologists might ask: How do employment and economic conditions play a role in families’ experiences? How do people in the United States view marriage and family differently than in other societies? With a social change lens, how do they view them differently over the years?

Consider the changes in U.S. families, one of the main institutions that sociologists study. The “typical” family in past decades consisted of married parents living in a home with their unmarried children. Today, the percentage of unmarried couples, same-sex couples, single-parent and single-adult households is increasing, as well as is the number of expanded households, in which extended family members such as grandparents, cousins, or adult children live together in the family home. While 15 million mothers still make up the majority of single parents, 3.5 million fathers are also raising their children alone (U.S. Census Bureau 2020). Increasingly, single people and cohabitating couples are choosing to raise children outside of marriage through surrogacy or adoption.

How do sociologists make sense of these changes? First, the pattern that humans have of forming families in most societies is considered a social fact. The expectations we have to form families are created by society and this tends to govern our social lives. Even if we decide not to marry or have children, we are influenced by this pattern.

Second, family is considered the most important of the agents of socialization, the significant individuals, groups, or institutions that influence our sense of self and the behaviors, norms, and values that help us function in society. That has prompted sociologists to devote significant attention to the study of the family as an institution.

Third, as culture shapes all of society, it also shapes the practices, values, beliefs, symbols, language and artifacts associated with family. Culture affects the way people behave in families, while families shape the larger culture of their communities.

Let’s examine these concepts through a peek into Australian Aboriginal culture (figure 2.15 shows Aboriginal Art in the Wunnumurra Gorge). Watch this 2:25-minute video, “What is meant by kinship?” in figure 2.16 that describes how culture shapes the very complex structure of Aboriginal families in Australia. What do you see as the marked difference between the kin structure that Colin Jones describes and the family structure that is familiar to you? What cultural practices, values, beliefs, etc. do you see expressed in the kinship structure he describes?

Figure 2.16 What is meant by kinship? [YouTube Video]

Kinship, for Australian Aboriginals, refers to a person’s responsibilities towards other people, the land and natural resources. It’s a system that determines how people relate to one another and their surroundings, responsibilities towards others, and how one relates to others through marriage, ceremony, funeral roles and behavior patterns. Members are asked to adhere to kinship principles through their actions, with the goal of creating a cohesive and harmonious community.

2.2.5 Levels of Analysis

Sociologists study all aspects and levels of society. Level of analysis in social sciences refers to the size or scale of the study population or social phenomenon. We tend to talk about this concept in terms of micro-level analysis (microsociology) and macro-level analysis (macrosociology).

Sociologists working with micro-level analysis study small groups and individual interactions. Micro-level analysis places a strong emphasis on context, meaning making, and interactions. It involves analyzing “what people do, say, and think in the actual flow of momentary experience (Collins 1981:984). As an example, a micro-level study might look at the accepted rules of conversation in various groups such as among teenagers or business professionals.

Sociologists who use macro-level analysis look at large scale social structures, trends among and between societies, institutions, and systems. The aspects of the society that are larger scale and exist over extended periods, such as changes in economies (Collins 1981). A macro-level analysis might focus research on how one institution impacts another, for example how religion influences politics. .

2.2.6 Inequality, Social Location, and Social Change

At the micro level, we can examine how society shapes our attitudes and behavior even if it does not determine them altogether. We still have freedom, but that freedom is limited by society’s expectations. At this level we can also see how our views and behavior depend to some degree on our social location in society.

Social location is defined as the social position an individual holds within their society. It is based upon social characteristics of social class, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, religion, and other characteristics that society deems important. The social location of an individual profoundly influences who they are and who they become, their interactions with others, and self-perception. Social location also profoundly affects opportunities of groups and of individuals because of social inequality.

2.2.6.1 Institutions and the Empowerment of Women and Girls

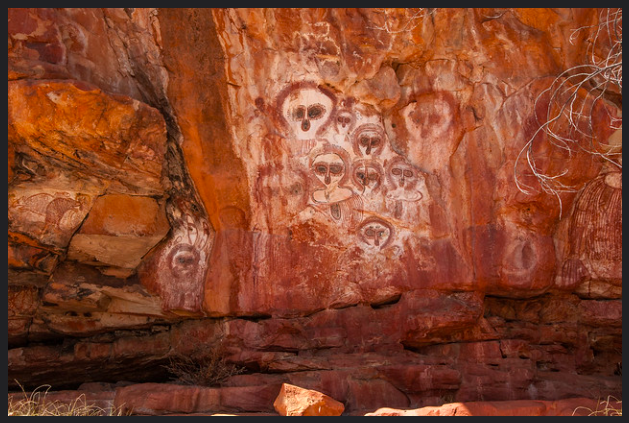

Let’s look closer at how institutions and structures interact with human behavior and social location with an example. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is an organization that works to find solutions to poverty, disease, and inequity around the world. One of their initiatives is the empowerment of women and girls, or the agency they express. Agency is the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change. As part of their strategy they look closely at how institutions play a role in their lives. Their web page explains it this way:

Institutional structures are the social arrangements, including both formal and informal rules and practices, that shape and influence women and girls’ ability to express agency and assert control over resources. The empowerment model locates institutional structures within four spheres in which women and girls live their lives: the family, community, market and state. Within each of these spheres, institutional arrangements are shaped by formal laws and policies, norms, and relations among groups and individuals (Bill and Melinda Gates n.d).

Figure 2.17 is an illustration of their model that applies this consideration of agency and institutional structures to their work. The agency of women and girls is at the center, because members of the foundation believe that as women are able to express their agency, they are better able to assert control over resources (depicted to the left). As women and girls are better able to assert resources, they are more empowered. On the right, the institutions of family, community, the market and the state are considered as influencers of women and girls’ agency. Each of those institutions carry two social facts the foundation considers important: norms, and laws and policies.

Figure 2.17 An illustration of a model used by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to address women and girls’ empowerment.

The Bill and Melinda Gates foundation sees addressing gender norms as crucial to making shifts in empowerment. Gender normsare the collectively held expectations and beliefs about how women, men, girls and boys should behave and interact in specific social settings and during different stages of their lives. Foundation members working on this project observe that “If a woman or girl challenges or does not conform to a norm, the consequences for her can range from subtle social exclusion to threats or acts of violence or, in extreme cases, death.” (Tips for Measuring Norms”).

One way the foundation tracks changes in norms in communities is by measuring whether or not community members think that women should have decision-making power over agricultural resources (Bill and Melinda Gates n.d). This way of measuring norms is called an indicator: a specific, observable, and measurable accomplishment or change that shows the progress made toward achieving a specific output or outcome

Within laws and policies, the foundation points to those established by international treaties and conventions, national governments, and local governments and authorities. Their model asserts that these laws and policies “ …affect whether, and under what conditions, women and girls have access to resources and opportunities.” To address the influence of laws and policies, for example, the foundation is working toward stronger legal provisions on women’s property and land rights. An indicator of progress toward this is how many women own property or resources for the production of goods, services and/or income in their own name (Bill and Melinda Gates n.d)

2.2.6.2 Social Stratification

Our social locations are framed in the context of social stratification: the system of social standing in society. Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into rankings based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and power. Typically, society’s layers, made of people, represent the uneven distribution of society’s resources. Society views the people with more resources as the top layer of the social structure of stratification.

Other groups of people, with fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers. An individual’s place within this stratification is called socioeconomic status (SES). Sociologists recognize social stratification as a society-wide system that makes inequalities apparent. While inequalities exist between individuals, sociologists are interested in larger social patterns.

Sociologists look to see if individuals with similar backgrounds, group memberships, identities, and location, share the same place in the social stratification system. No individual, rich or poor, can be blamed for social inequalities. Instead all participate in a system where some rise and others fall. Most Americans believe the rising and falling is based on individual choices. But sociologists see how the structure of society affects a person’s social standing and therefore is created and supported by society.

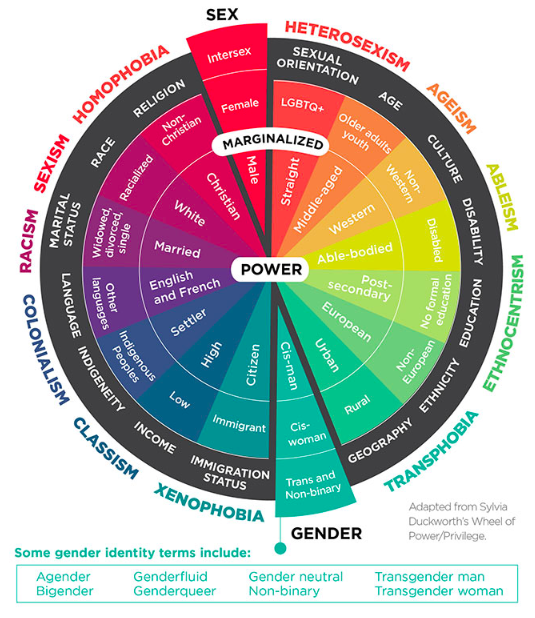

2.2.6.3 Intersectionality

Intersectionality is the idea that inequalities produced by multiple and interconnected social characteristics influence the life of an individual or group. Intersectionality, then, suggests that we should view gender, race, class, and sexuality not as individual characteristics but as interconnected social situations.

Intersectionality studies have their origins with the Combahee River Collective. The collective was founded in 1974 by a group of black feminist women in the United States who challenged how white feminist and civil rights movements did not address the needs of black women. Much of the research in this field has its roots – not just in academic discourse – but in attempts to initiate social change.

Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw, a US civil rights advocate and law professor, coined the term intersectionality. She highlights the ways that gender and race have been historically separated into separate fields of study. The theory of intersectionality reflects multiple perspectives, places emphasis on lived experiences, and creates visibility around perspectives of marginalized groups. In this way, issues of discrimination, ageism, classism and others can be seen in the multiple-layered frames that they exist.

Watch this 5:47-minute video, “Kimberlé Crenshaw at Ted + Animation” (figure 2.18) for her explanation of the importance of seeing our interactions with intersectionality. Can you think of an instance like Emma’s in the video, that is best seen through the lens of intersectionality?

Figure 2.18 Kimberlé Crenshaw at Ted + Animation [YouTube Video]

Take a look at the image in figure 2.19 that depicts intersectionality. Imagine each concentric piece as movable wheels, creating a variety of experiences for individuals based on their combined social characteristics. Where can you find yourself and your experiences on the wheel?

Figure 2.19: Image of wheel depicting intersectionality Image Description

2.2.7 Going Deeper

For an in-depth introduction to a number of these concepts and terms, see sections of the text, Sociology in Everyday Life.

For more on sociology, sociological imagination, social structure, agency, and the sociological perspective: see Chapter 1: Introduction to Sociology In Sociology of Everyday Life.

For more on stratification see: Chapter 8: Social Stratification and Class Sociology of Everyday Life.

For more on race and ethnicity as a social location see: Chapter 11: Race and Ethnicity Sociology of Everyday Life.

For more on gender as a social location: see Chapter 9: Gender: Identities, Interactions, and Institutions Sociology of Everyday Life.

For more on sexuality as a social location see Chapter 10: Sexuality Sociology of Everyday Life.

See the Stanford Open Policing Project for more info on traffic stops by law enforcement agencies across the U.S.

To better understand Australian aboriginal kinship, watch the videos: “Aboriginal Kinship presentation: Nations, Clans and Family Groups”, “Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Skin Names” and “Aboriginal Kinship Presentation: Moiety”

2.2.8 Licenses and Attributions for How Sociologists Study Social Change

“How Sociologists Study Social Change” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0., with the exception of:

“How Sociologists Study Social Change, paragraph 1” is adapted from “1.1What is Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax Sociology 3e is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social problems.

“How Sociologists Study Social Change, paragraph 2 – ?” is adapted from “1.1 The Sociological Perspective”, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA, photo, video and explanatory text added.

Figure 2.4: Photo of Woman Holding Elevator Door

Figure 2.5: Title of Video: “6 – Candid Camera (Elevator)”

Figure 2.6 Photo of C. Wright Mills. Image by Gambar Fritz Goro Fair Use

Figure 2.7.Photo of C. Wright Mills. Image by Yaroslava Mills and (c) Nik Mills. Fair Use

Figure 2.8 Title of Video: “The Sociological Imagination”

Figure 2.9 screenshot of the City of Portland’s web page, listing regulations related to pedestrian rules at crosswalks. Fair Use

“Social Construction and our Identities” is adapted from “4.3 Social Constructions of Reality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax Sociology 3e is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social change. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/4-3-social-constructions-of-reality

Figure 2.10 Title of Video, “Are We Who We Think We Are?”

“The Debunking Motif” is adapted from “1.1 The Sociological Perspective”, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA,

“Structures and Institutions” is adapted from “Sociological Perspective” by Gougherty and Puentes, Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Prezi added

Figure 2.11 Prezi Illustration of Social Institutions by Elizabeth Berrios

“Systems and Systems Thinking” is adapted from “1.3 The Environment is a System” Alexanda Geddes, in Terrestrial Environment Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License reorganized, edited for brevity and context of this chapter.

Figure 2.12 Visualization of the National Performance Framework of the Scottish Government, a model based on systems thinking. Fair Use, but check permissions in future edition.

“Culture” is a remix of “https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/3-1-what-is-culture

and “6.2.2 Social Sciences” in “6.2 What Is Culture?”by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.13 Mongolian Family Member in front of their ger (yurt) home

“Social Facts” is adapted from “Sociological Perspective” by Gougherty and Puentes Sociology in Everyday Life , licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 2.14 Image of a vase, depicting the Greek Hero, Ajax, preparing for his suicide.

Figure 2.15 Image of Aboriginal Art, Wunnumurra Gorge

“The Institution of Family ” is adapted from “1.1 What is Sociology” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax Sociology 3e is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social change.

Figure 2.16 Title of Video, “What is meant by kinship?”

“Levels of Analysis” is a remix of “Levels of Analysis: Macro Level and Micro Level” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Inequality, Social Location and Social Change ” is adapted from “8.2 What is Stratification?” by Gougherty and Puentes Sociology in Everyday Life , licensed under CC BY 4.0 except except for Institutions and the Empowerment of Women and Girls

Figure 2.17 An illustration of a model used by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to address women and girls’ empowerment.

“Social Stratification ” is a remix of“8.2 What is Stratification?” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Intersectionality ” is a remix of “2.6 Social Theory Today” by Gougherty and Puentes in Sociology in Everyday Life, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Added video and image of wheel

Figure 2.18. Title of Video: “Kimberlé Crenshaw at Ted + Animation”

Figure 2.19. A wheel depicting intersectionality Used with permission