7.7 Educational Change in Action: Closing the Digital Divide

When you think about how often you use your phone to find a restaurant, get directions, or look up the actors in your favorite movie, you are using technology to solve problems. In 1999 foundation leader Shelley Morrisette wrote about the digital divide, specifically noticing that internet users at that time were more educated and wealthier than non-internet users. Since then the digital divide has become widely used to describe not only internet use but access to computers and smartphones, access to free or low cost, stable internet, and digital literacy. These three components of device, access and effective skills are referred to as the three legged stool needed to close the digital divide. Individuals need a computer that they know how to use effectively, and sufficient quality internet service to participate effectively.

Since the original creation of the phrase digital divide, researchers have examined who is divided. As you might expect, socioeconomic class is a strong predictor of who has access to technology and the internet. In early research, geographic location predicted where you landed in the divide. Residents of bigger cities were more likely to have internet access. Inner-city and rural residents were less likely to have access. Race/ethnicity, gender, and age also impacted access to technology and training. The digital divide itself is a manifestation of a social problem, both because it impacts people worldwide, and because there is significant inequality based on people’s social location.

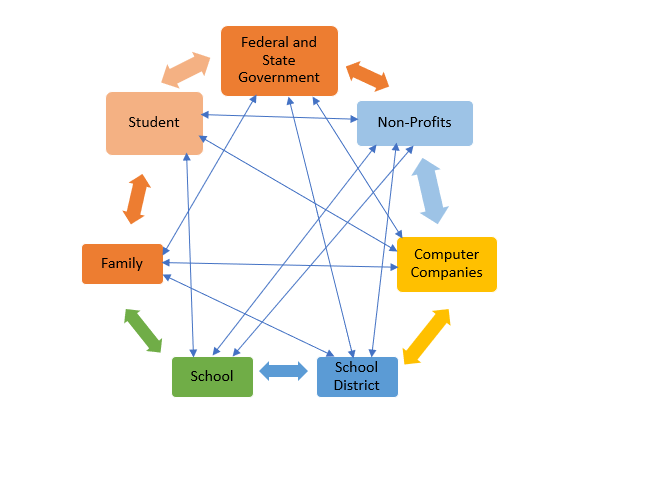

As we discussed earlier in this chapter, families are having widely different experiences of education during COVID-19, based often on their ability to access resources for learning. Unlike many social problems, closing the digital divide has accelerated during COVID-19. Also, it’s not that people are protesting in the streets to create social change in this area. Instead, we see a wide array of government, corporate, non-profit, and community agencies working together to provide access to online education. Each of the partners contributes something unique to getting all of our students and their families back in the classroom. Also, as each partner contributes a part of the solution, the other partners respond and react, illustrating the interdependent nature of solving social problems and highlighting that they must be solved collectively.

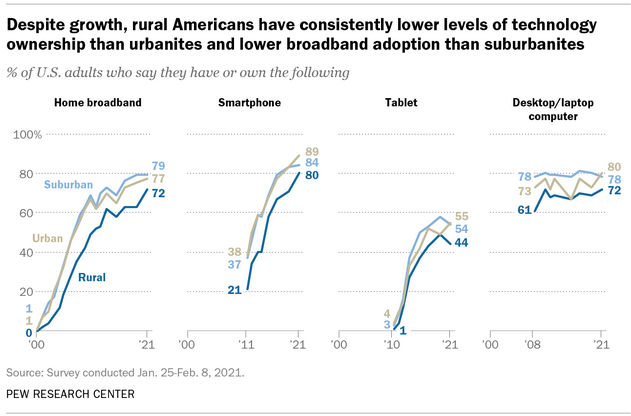

As early as 2018, Pew Research was reporting that nearly 1 in 5 students couldn’t finish their homework because they didn’t have access to the internet (Pew 2018). When you look at the gap across gender, race, class, and ability/disability, the gap is closing. The graph in figure 7.25 shows widespread adoptions of technology between 2000 and 2021 in all geographic locations. People in rural areas still own less technology than people who live in cities or suburbs.

Figure 7.25. Rural American have consistently lower levels of technology

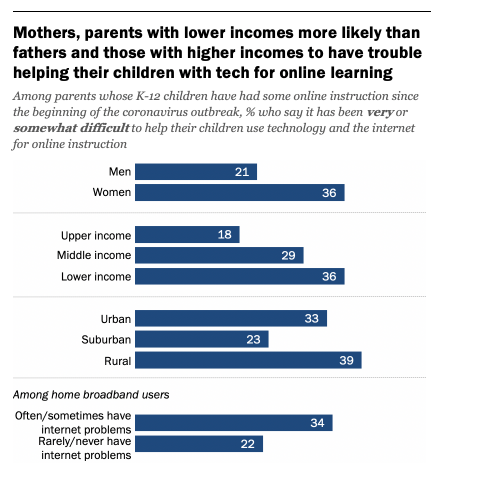

You may have experienced going on line for school during COVID-19. Because many schools closed, online education became critical for providing education. This made the digital divide more visible. Many parents struggled to help their kids with technology, as shown in figure 7.26. When we examine this detail, we see that women, people with lower incomes and rural families struggle the most with this problem.

Figure 7.26. Mothers and parents with low income have more trouble than fathers and people with higher incomes helping children with on line tech

At the same time our society worked to create interdependent solutions to closing the digital divide so that students could learn. Students and families bought computers and learned how to use them better. Federal and state governments and individual school districts acted with collective action to provide money to improve internet access and distribute internet equipment. Non-profit organizations and computer companies provided training and technology for adults not going to school. Schools and teachers moved classes online quickly so that students could learn. The figure in 7.27 shows the connections that enabled interdependent solutions. Let’s examine these actions in more detail.

Figure 7.27. Interdependent Solutions to Educational during COVID-19

Among many federal government responses to COVID-19, two specific efforts are useful to mention. First, the federal government launched the Emergency Broadband benefit program in Feb 2021, paying a portion of the internet bill for low-income families. This program also allowed school districts and school libraries to apply for grants to buy and support computers, hotspots and internet connectivity. The program transitioned to the Affordable Connectivity Program in March 2022, expanding the program to more households, adding Pell grant recipients and free lunch program students as potential recipients, and stabilizing government funding for this program.

Second, the Federal Government funded the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Fund (or GEER Fund) in 2020. These funds are allocated to each state to stabilize education in that state during the pandemic. The governors in each state get to decide how to spend those funds to help students, families, teachers, and schools. In Oregon and at Oregon Coast Community College, we see GEER money being used in multiple ways. OCCC distributed some money directly to students in need. The college purchased laptops and hotspots for student use. Statewide, GEER money was used to fund the Open Oregon Guided Pathways project (of which this book is a part), to create free Sociology, Criminal Justice, and Human Development and Family Science textbooks and courses for all students. Each state is applying federal GEER money differently. Do you know what is happening in your state?

Together, the federal government and the state of Oregon are managing the e-Rate program, a program that funds internet access for schools and school libraries. These and other government-funded programs are allowing/supporting/encouraging schools to step up to be actors in closing the digital divide.

Non-profit social service providers highlight digital skills as a support to stabilizing families. Goodwill, for example, hosts a digital learning platform called GFCLearnfree.org, which hosts educational content that helps people learn to use their computers, search for jobs online, and manage their money more effectively. However, access alone does not help people learn effectively. Some non-profits are taking a much more integrated approach.

EveryoneOn is a US-based nonprofit which takes a multifaceted approach to closing the digital divide. They were founded in 2012 to meet the federal government’s challenge to digitally connect everyone. They developed a locator application which allows people to find low cost internet services in their area. This expanded into a locator which not only highlights internet services, but provides options for purchasing low cost computers.

In addition to this technology differentiator, they build partnerships to support digital literacy. EveryoneOn partners with technology companies in local areas to provide the devices and technology support at no cost to program participants. They also partner with local service providers who connect them with the people who need their services. Finally, they provide digital literacy training to low income people. Their initial offering was an on-ground class to help senior citizens in Miami to use their phones more effectively.

As a response to the pandemic, they developed a hybrid model, in which clients get initial support for their new computers in person from EveryoneOn and their service provider. Then EveryoneOn provides online classes that teach how to use zoom, how to send email, and how to keep personal information safe among other digital literacy skills. This organization is particularly committed to closing the digital divide among communities of color, providing services in Spanish and English. The community building that EveryoneOn is growing is essential in translating policy and funding into action.

Finally, we see individuals taking action to close the digital divide. You, yourself, may be a person who now knows how to use Zoom or google slides to do your school work. You may be a parent with a child who needs to log in to be at a school every day. You may be a teacher who is working fast to create learning opportunities that work for your student. Or, you may be a person who is creating applications which help the rest of us.

Although we still have work to do, the response of educators, business, non-profits, and government is adding even more people to the digital superhighway. Although the digital divide is far from closed, the interconnected responses across individuals and institutions is a reason for hope.

7.7.1 Licenses and Attributions for Educational Change in Action: Closing the Digital Divide

“Educational Change in Action: Closing the Digital Divide” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

Figure 7.24 Title of Video: Dr. Christopher Emdin: Hip Hop Ed in the Classroom (time: 2:14)

Figure 7.26. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/09/01/parents-their-children-and-school-during-the-pandemic/

Figure 7.27. Interdependent Solutions to Education during COVID-19 by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.