9.2 The Sociology of Social Movements

Figure 9.7. A protest of the human rights violations at Guantanamo Bay Prison

Activism can take the form of enormous marches, violent clashes, fundraising, social media activity, or silent displays. In this 2016 photo (figure 9.7), people wear hoods and prison jumpsuits to protest human rights violations at Guantanamo Bay Prison, where suspected terrorists had been held for over a decade without trial and without the rights of most people being held for suspicion of crimes.

When considering social movements, the images that come to mind are often the most dramatic and dynamic: the Boston Tea Party, Martin Luther King’s speech at the 1963 March on Washington, and anti-war protesters putting flowers in soldiers’ rifles, hooded men posing as Guantanamo Bay prisoners to protest conditions there (figure 9.7). Or perhaps more violent visuals: burning buildings in Watts, protestors fighting with police, or a lone citizen facing a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square.

Occupy Wall Street (OWS) was a unique movement that defied some of the theoretical and practical expectations regarding social movements. OWS is set apart by its lack of a single message, its leaderless organization, and its target—financial institutions instead of the government. OWS baffled much of the public, and certainly the media, leading many to ask, “Who are they, and what do they want?”

On July 13, 2011, the Canadian based organization Adbusters posted on its blog, “Are you ready for a Tahrir moment? On September 17th, flood into lower Manhattan, set up tents, kitchens, peaceful barricades and occupy Wall Street” (Castells 2012).

The “Tahrir moment” was a reference to the Arab Spring, a 2010 political uprising in response to corruption and economic stagnation. It began in Tunisia and spread throughout the Middle East and North Africa, including Egypt’s Tahrir Square in Cairo (figure 9.8). Although OWS was a reaction to the continuing financial chaos that resulted from the 2008 market meltdown and not a political movement, the Arab Spring was its catalyst.

Figure 9.8. Over 6 million protestors in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt demanding the removal of the regime and for President Mubarak to step down.

Manuel Castells (2012) notes that the years leading up to the Occupy movement had witnessed a dizzying increase in the disparity of wealth in the United States, stemming back to the 1980s. The top 1 percent in the nation had secured 58 percent of the economic growth in the period for themselves, while real hourly wages for the average worker had increased by only 2 percent. The wealth of the top 5 percent had increased by 42 percent. The average pay of a CEO was at that time 350 times that of the average worker, compared to less than 50 times in 1983 (AFL-CIO 2014).

The country’s leading financial institutions, to many clearly to blame for the crisis and dubbed “too big to fail,” were in trouble after many poorly qualified borrowers defaulted on their mortgage loans when the loans’ interest rates rose. The banks were eventually “bailed” out by the government with $700 billion of taxpayer money. According to many reports, that same year top executives and traders received large bonuses.

On September 17, 2011 the occupation began. About one thousand protestors descended upon Wall Street, and up to 20,000 people moved into Zuccotti Park, only two blocks away, where they began building a village of tents and organizing a system of communication. The protest soon began spreading throughout the nation, and its members started calling themselves “the 99 percent.” More than a thousand cities and towns had Occupy demonstrations.

What did they want? Castells has dubbed OWS ” a non-demand movement: The process is the message.” Using Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and live-stream video, the protesters conveyed a multifold message with a long list of reforms and social change, including the need to address the rising disparity of wealth, the influence of money on election outcomes, our corporatized political system (to be replaced by “direct democracy”), political favoring of the rich, and rising student debt.

What did they accomplish? Despite headlines at the time softly mocking OWS for lack of cohesion and lack of clear messaging, the movement is credited with bringing attention to income inequality and the seemingly preferential treatment of financial institutions accused of wrongdoing. Many financial crimes are not prosecuted, and their perpetrators rarely face jail time (figure 9.9). It is likely that the general population is more sensitive to those issues than they were before the Occupy and related movements made them more visible.

Figure 9.9. A protestor affiliated with Occupy Wall Street.

What is the long-term impact? Has the United States changed the way it manages inequality? Certainly not. Income inequality has generally increased. But is a major shift in our future?

The late James C. Davies suggested in his 1962 paper, “Toward a Theory of Revolution” that major change depends upon the mood of the people, and that it is extremely unlikely those in absolute poverty will be able to overturn a government, simply because the government has infinitely more power.

Instead, a shift is more possible when those with more power become involved. When formerly prosperous people begin to have unmet needs and unmet expectations, they become more disturbed: their mood changes. Eventually an intolerable point is reached, and revolution occurs. Thus, change comes not from the very bottom of the social hierarchy, but from somewhere in the middle (Davies 1962). For example, the Arab Spring was driven by mostly young, educated people whose promise and expectations were thwarted by corrupt autocratic governments. OWS too came not from the bottom but from people in the middle, who exploited the power of social media to enhance communication.

While most of us learned about social movements in history classes, we tend to take for granted the fundamental changes they caused —and we may be completely unfamiliar with the trend toward global social movements. But from the anti tobacco movement that has worked to outlaw smoking in public buildings and raise the cost of cigarettes, to political uprisings throughout the Arab world, movements are creating social change on a global scale.

9.2.1 Levels of Social Movements

Movements happen in our towns, in our nation, and around the world. Let’s take a look at examples of social movements, from local to global. No doubt you can think of others on all of these levels, especially since modern technology has allowed us a near-constant stream of information about the quest for social change around the world.

9.2.1.1 Local

Local social movements typically refer to those in cities or towns, but they can also affect smaller constituencies, such as college campuses. Sometimes colleges are smaller hubs of a national movement, as seen during the Vietnam War protests or the Black Lives Matter protests. Other times, colleges are managing a more local issue.

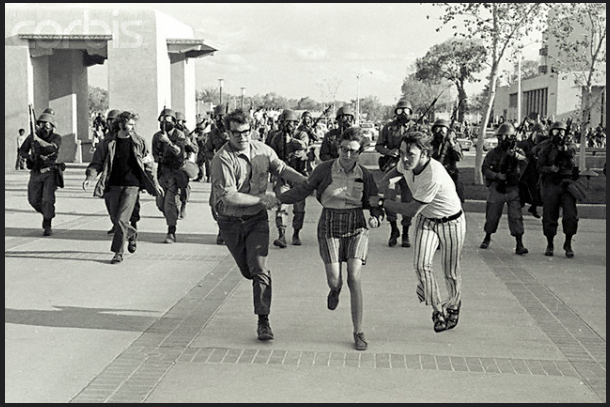

Figure 9.10. May 1970, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA—Following the May 4, 1970 shooting of students at Kent State University during an anti-Vietnam war protest there. Here, students at UNM took over the student union building. After several days of the occupation the National Guard were called upon to clear the students from the building.

One example of a campus focused social movement occurred in Wisconsin. After announcing a significant budget shortfall, Governor Scott Walker put forth a financial repair bill that would reduce the collective bargaining abilities of unions and other organizations in the state. (Collective bargaining was used to attain workplace protections, benefits, healthcare, and fair pay.)

Faculty at the state’s college system were not in unions, but teaching assistants, researchers, and other staff had regularly collectively bargained. Faced with the prospect of reduced job protections, pay, and benefits, the staff members began one of the earliest protests against Walker’s action, by protesting on campus and sending an ironic message of love to the governor on Valentine’s Day. Over time, these efforts would spread to other organizations in the state.

9.2.1.2 State

The most impactful state-level protest would be to cease being a state, and organizations in several states are working toward that goal. Texas secession has been a relatively consistent movement since about 1990. The past decade has seen an increase in rhetoric and campaigns to drive interest and support for a public referendum (a direct vote on the matter by the people). The Texas Nationalist Movement, Texas Secede!, and other groups have provided formal proposals and programs designed to make the idea seem more feasible.

States also get involved before and after national decisions. The legalization of same-sex marriage throughout the United States led some people to feel their religious beliefs were under attack. Following swiftly upon the heels of the Supreme Court Obergefell ruling, the Indiana legislature passed a Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA, pronounced “rifra”) (Figure . Originally crafted decades ago with the purpose of preserving the rights of minority religious people, more recent RFRA laws allow individuals, businesses, and other organizations to decide whom they will serve based on religious beliefs.

Figure 9.11. A Marriage Equality Decision Day rally in front of the US Supreme Court, June, 26, 2015. The ruling allowing same sex couples to marry legally prompted members of Indiana to push for the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, allowing individuals, businesses, and other organizations to decide whom they will serve based on religious beliefs.

For example, Arkansas’s 2021 law allowed doctors to refuse to treat patients based on the doctor’s religious beliefs (Associated Press 2021). In this way, state-level organizations and social movements are responding to a national decision.

9.2.1.3 Global

Social organizations worldwide take stands on such general areas of concern as poverty, sex trafficking, and the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in food. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are sometimes formed to support such movements, such as the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movement (FOAM). We introduced the Fair Trade movement in Chapter 3. It was developed to protect and support food producers in poor countries. Occupy Wall Street, although initially a local movement, also went global throughout Europe and the Middle East.

9.2.2 Types of Social Movements

We know that social movements can occur on the local, national, or even global stage. Are there other patterns or classifications that can help us understand them? Sociologist David Aberle (1966) addresses this question by developing categories that distinguish among social movements based on what they want to change and how much change they want.

Reform movements seek to change something specific about the social structure. Examples include antinuclear groups, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), the Dreamers movement for immigration reform (figure 9.12), and the Human Rights Campaign’s advocacy for Marriage Equality.

Figure 9.12. The Dreamers Movement became prominent beginning in 2000, when more than one million children and youths found themselves in a similar situation with their shared immigration status. They had migrated to the United States as children without any authorization and grew up without legal status. The Relief and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act is a national piece of legislation proposed to provide a pathway to permanent residency and U.S. citizenship for qualified undocumented immigrant students.

Revolutionary movements seek to completely change every aspect of society. These include the 1960s counterculture movement, including the revolutionary group The Weather Underground, as well as anarchist collectives. Texas Secede! is a revolutionary movement.

Religious/Redemptive movements are “meaning seeking,” and their goal is to provoke inner change or spiritual growth in individuals. Organizations pushing these movements include Heaven’s Gate or the Branch Davidians. The latter is still in existence despite government involvement that led to the deaths of numerous Branch Davidian members in 1993.

Alternative movements are focused on self-improvement and limited, specific changes to individual beliefs and behavior. These include trends like transcendental meditation or a macrobiotic diet.

Resistance movements seek to prevent or undo change to the social structure. The Ku Klux Klan, the Minutemen, and pro-life movements fall into this category.

9.2.3 Stages of Social Movements

Sociologists also study the lifecycle of social movements—how they emerge, grow, and in some cases, die out. Blumer (1969) and Tilly (1978) outline a four-stage process. In the preliminary stage, people become aware of an issue, and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage when people join together and organize in order to publicize the issue and raise awareness.

In the institutionalization stage, the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically with a paid staff. When people fall away and adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or when people no longer take the issue seriously, the movement falls into the decline stage. Each social movement discussed earlier belongs in one of these four stages. Where would you put them on the list?

9.2.4 Social Media and Social Movements

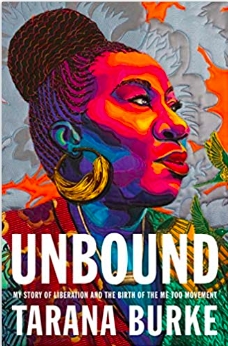

As you have likely experienced in your life, social media is a widely used mechanism in social movements. Tarana Burke first used “Me Too” in 2006 on a major social media venue of the time (MySpace). The phrase later grew into a massive movement when people began using it on Twitter to drive empathy and support regarding experiences of sexual harassment or sexual assault (figures 9.13 and 9.14). In a similar way, Black Lives Matter began as a social media message after George Zimmerman was acquitted in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, and the phrase burgeoned into a formalized (though decentralized) movement in subsequent years.

Figures 9.13 and 9.14. Tarana Burke, activist from New York City, started the MeToo movement via MySpace in 2006: MeToo is a global, and survivor-led, movement against sexual violence, helping other women with similar experiences to stand up for themselves; Tarana published a memoir, “Unbound” about her own journey in launching the MeToo movement.

Social media has the potential to dramatically transform how people get involved in movements ranging from local school district decisions to presidential campaigns. Social media adds a dynamic to each of the stages. In the preliminary stage, people become aware of an issue, and leaders emerge. Compared to movements of 20 or 30 years ago, social media can accelerate this stage substantially. Issue awareness can spread at the speed of a click, with thousands of people across the globe becoming informed at the same time. In a similar vein, those who are savvy and engaged with social media may emerge as leaders, even if, for example, they are not great public speakers.

At the next stage, the coalescence stage, social media is also transformative. Coalescence is the point when people join together to publicize the issue and get organized. President Obama’s 2008 campaign was a case study in organizing through social media. Using Twitter and other online tools, the campaign engaged volunteers who had typically not bothered with politics. Combined with comprehensive data tracking and the ability to micro-target, the campaign became a blueprint for others to build on.

The campaigns and political analysts could measure the level of social media interaction following any campaign stop, debate, statement by the candidate, news mention, or any other event, and measure whether the tone or “sentiment” was positive or negative. Political polls are still important, but social media provides instant feedback and opportunities for campaigns to act, react, or—on a daily basis—ask for donations based on something that had occurred just hours earlier (Knowledge at Wharton 2020).

Interestingly, social media can have interesting outcomes once a movement reaches the institutionalization stage. In some cases, a formal organization might exist alongside the hashtag or general sentiment, as is the case with Black Lives Matter. At any one time, BLM is essentially three things: a structured organization, an idea with deep and personal meaning for people, and a widely used phrase or hashtag.

It’s possible that users of the hashtag are not referring to the formal organization. It’s even possible that people who hold a strong belief that Black lives matter do not agree with all of the organization’s principles or its leadership. And in other cases, people may be very aligned with all three contexts of the phrase. Social media is still crucial to the social movement, but its interplay is both complex and evolving. Sociologists have identified high-risk activism, such as the civil rights movement, as a “strong-tie” phenomenon, meaning that people are far more likely to stay engaged and not run home to safety if they have close friends who are also engaged.

Social media had been considered “weak-tie” (McAdam 1993 and Brown 2011). People follow or friend people they have never met. Weak ties are important for our social structure, but they seem to limit the level of risk we’ll take on their behalf. For some people, social media remains that way, but for others it can relate to or build stronger ties. For example, if people, who had for years known each other only through an online group, meet in person at an event, they may feel far more connected at that event and afterward than people who had never interacted before. Social media itself, even if people never meet, can bring people into primary group status, forming stronger ties.

9.2.5 Theoretical Perspectives on Social Movements

Figure 9.15. Protestors affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) march in Montgomery, March of 1965.

Figure 9.16. This mural in honor of civil rights hero John Lewis (1940 – 2020), painted by artist Sean Schwab was dedicated in Atlanta in August, 2012. John Lewis was one of the “Big Six” leaders in the American Civil Rights Movement and chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), playing a key role in the struggle to end legalized racial discrimination and segregation. He was elected as the U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th congressional district in 1986 and served 17 terms.

Most theories of social movements are called collective action theories, indicating the purposeful nature of this form of collective behavior. The following three theories are but a few of the many classic and modern theories developed by social scientists.

9.2.5.1 Resource Mobilization

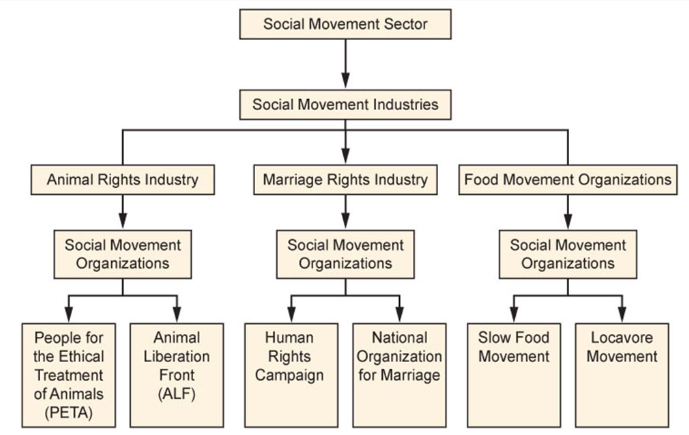

McCarthy and Zald (1977) conceptualize resource mobilization theory as a way to explain movement success in terms of the ability to acquire resources and mobilize individuals. Resources are primarily time and money, and the more of both, the greater the power of organized movements. Numbers of social movement organizations (SMOs), which are single social movement groups, with the same goals constitute a social movement industry (SMI). Together they create what McCarthy and Zald (1977) refer to as “the sum of all social movements in a society.”

9.2.5.1.1 Resource Mobilization and the Civil Rights Movement

An example of resource mobilization theory is activity of the civil rights movement in the decade between the mid 1950s and the mid 1960s. Social movements had existed before, notably the Women’s Suffrage Movement and a long line of labor movements. The civil rights movement had also existed well before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat to a white man. Her arrest triggered a public outcry that led to the famous Montgomery bus boycott, turning the movement into what we now think of as the “civil rights movement” (Schmitz 2014).

Mobilization had to begin immediately. Boycotting the bus made other means of transportation necessary, which was provided through car pools. Churches and their ministers joined the struggle, and the protest organization In Friendship was formed as well as The Friendly Club and the Club From Nowhere. A social movement industry was growing.

Martin Luther King Jr. emerged during these events to become the charismatic leader of the movement, gained respect from elites in the federal government, and aided by even more emerging social movement organizations, such as the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) (figures 9.15 and 9.16), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), among others.

With each of these steps a social movement sector developed, and several social movement industries developed (figure 9.17). Although the movement in that period was an overall success, and laws were changed (even if not attitudes), the “movement” continues. Several organizations that began in the 50s and 60s exist today. So do struggles to keep the gains that were made, even as the U.S. Supreme Court has recently weakened the Voter Rights Act of 1965, once again making it more difficult for Black Americans and other minorities to vote.

Figure 9.17. Multiple social movement organizations concerned about the same issue form a social movement industry. A society’s many social movement industries comprise its social movement sector. With so many options, to whom will you give your time and money?

9.2.5.2 New Social Movement Theory

New social movement theory, a development of European social scientists in the 1950s and 1960s, attempts to explain the proliferation of postindustrial and postmodern movements that are difficult to analyze using traditional social movement theories. Rather than being one specific theory, it is more of a perspective that revolves around understanding movements as they relate to politics, identity, culture, and social change.

Some of these more complex interrelated movements include ecofeminism, which focuses on the patriarchal society as the source of environmental problems, and the transgender rights movement. Sociologist Steven Buechler (2000) suggests that we should be looking at the bigger picture in which these movements arise—shifting to a macro-level, global analysis of social movements.

9.2.6 Social Movements in Theory and Action

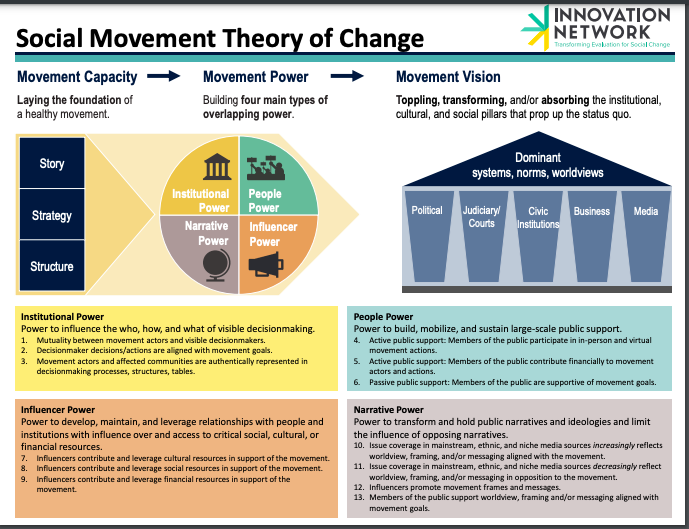

Sometimes social scientists contribute to direct theories of change for specific movements. For example the Social Movement Learning Project outlines a complex map for creating change and for evaluating change through social movements. Take a look at their visual below. They describe how movement capacity, movement power, and movement vision are all necessary for change. Similarly, the map outlines how institutional power, influencer power, people power, and narrative power are all key elements of successful social movement making.

Figure 9.18. Innovation Network’s Theory of Change.

The basic sociology of social movements includes an examination of the levels, types, and stages of social movements, and analyzes social movements through the lens of theoretical perspectives. The rest of this chapter will explore the social movements associated with the environmental crisis. We’ll begin by exploring how sociology observes our environmental challenges so we can better understand the social response.

9.2.7 Licenses and Attributions for The Sociology of Social Movements

“The Sociology of Social Movements” except for “Social Movements in Theory and Action” is adapted from “Introduction to Social Movements and Social Change” , “Collective Behavior” and “Social Movements” sections of Chapter 21, “Social Movements and Social Change” found in Introduction to Sociology 3e and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Edited for brevity and context. Figures have been changed and added.

“Social Movements in Theory and Action” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.7 is provided by Debra Sweet, published on Flickr, and licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.8. Over 6 million protestors in Tahrir Square demanding the removal of the regime and for Mubarak to step down by Jonathan Rashad is published by Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.9. Occupy Wall Street protestor by Boris D. Leak si published by Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.10 May 1970, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA by Andy is published by Flickr under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.11 A Marriage Equality Decision day rally by Elvert Barnes is published by Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.12. The Dreamers movement by Molly Adams is published on Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.13. Tarana Burke, activist from New York City is published on Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Figure 9.14. Tarana published a memoir, “Unbound” about her own journey in launching the MeToo movement is published with fair use.

Figure 9.15. Protestors affiliated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) is published by Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.16. mural in honor of civil rights hero John Lewis is published on Flickr under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.17. Multiple social movement organizations concerned about the same issue form a social movement industry.

Figure 9.18. “Social Movement Theory of Change” is found at Innovation Network and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.