1.3 Diverse Experiences of Social Change

How can we best identify the social changes that influence us and our communities? And how can we best see the social changes that we help create? Because we live enmeshed within the culture of our residence, it can be difficult to see some aspects of our own society. You might be more aware of some social changes better than others. Some changes are severe, receiving plenty of news and social media attention. Other changes tend to need more study to be able to see.

For example, some social changes that have erupted due to COVID-19 are undoubtedly very evident to you. Nearly our entire globe has experienced dramatic changes in lifestyle. Many of us have endured lengthy and isolating stretches of quarantine, stress about our health and the health of our loved ones, changes to work, whether working remotely or working more, and a shift to school at home.

Other changes sparked by COVID-19 are less visible. Lifestyle changes forced by a global pandemic have shifted relationships. Extended families have been isolated from each other, breaking links to emotional support. For example, some families have even been unable to gather for funerals. Through the work of research, we know there has been an increase in domestic violence in the United States since the lockdowns began (Cannon et al. 2021).

Some researchers point to relational silver linings of the pandemic, sharing that some people have found new positive meaning related to family, opportunities for strengthening relationships, improved appreciation, gratitude, and tolerance (Evans, Mikocka-Walus, Klas et al. 2020). Other research shows that for some, digital tools have taken on new relevance, as the pandemic prompted them to use unfamiliar technology or the internet in new ways. Many of these changes are difficult to see, because we are living them in the moment.

It’s often easier to see the role of social change in our own lives when we first examine societies and cultures different from our own. We introduced this chapter with stories from France for that reason. Let’s look at a few more societies whose specific circumstances frame unique ways of experiencing social change.

1.3.1 Social Change and the Environment: the Sámi People

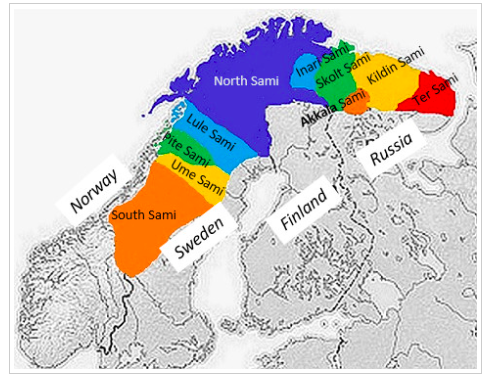

Figure 1.11. A map showing Sapmi, the Sámi people’s own name for their traditional territory, the approximate distribution of the various Sami territories, and Sámi language groups.

One way to look at how different societies experience social change is by looking at the circumstances that impact them the most. As our global warming crisis advances, we increasingly see societies that are dramatically impacted by environmental changes. The Sámi people are the Indigenous people of the northern part of the Scandinavian Peninsula and large parts of the Kola Peninsula which is almost completely inside the Arctic Circle.

The compilation of these areas in Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia is called Sapmi, the Sámi people’s own name for their traditional territory. There, they number between 80,000 and 100,000. Figure 1.11 shows the approximate distribution of the various Sámi territories and language groups.

1.3.1.1 Reliance on reindeer: Environmental vulnerability

Figure 1.12. Reindeer standing in the snow [Flickr Video] by Karl Chan.

Figure 1.12. Reindeer standing in the snow [Flickr Video] by Karl Chan.

Sámi identity, culture, and survival; their entire way of life is based on the ancient practice of reindeer herding. Meet some especially charming reindeer in the 12-second video in figure 1.12. Each year Sami families follow the seasonal migration patterns of reindeer, moving between winter and summer grazing territories. Sámi people use all parts of the reindeer for their sustenance. Rebecca Harris, a writer for the Indigenous rights organization Cultural Survival explains:

Bone marrow fortifies soups. Iron-rich pancakes made from reindeer blood are traditionally fed to pregnant women. The animals’ bones, sinews, skin, and fur are vital ingredients in the traditional Sami craft called duodji. Men traditionally use antlers, bones, and wood to make dishes and sleds. Leg bones are used as stoppers in Sami reindeer lassos. Women use reindeer fur and skin to make outdoor clothing—shoes, hats, gloves, and jackets (Harris 2007).

Herders earn a living by selling reindeer for meat as well as for their hides, which is both sold across Scandinavia and exported (Cohen 2018). They harvest seasonal food resources such as berries and herbs, living in considerable balance with nature and avoiding resource depletion. Sámi people also pay close attention to different reindeer behaviors and how they respond to changes in their environment (The Environmental Justice Foundation 2019).

The 3:23-minute video in figure 1.13, “People under the northern lights,” highlights the life of 83-year old Karen Anna, a Sami reindeer herder. As you watch, what do you notice is Karen Anna’s focus when she talks of how life was different when she was a child? What do you notice is her focus when she talks of life before the 1960s?

Figure 1.13. People under the northern lights | Sami reindeer herder Karen Anna from Visit Norway on Vimeo. You will want to turn on the closed captioning (CC) to see subtitles in your language. (The CC button is in the bottom right corner of the video player.)

1.3.1.2 Social change experienced in Sapmi

Karen Anna refers to life before the 1960s by referencing the snowmobile, which changed Sámi herding practices dramatically. She shares how important it is to check the quality of land for reindeers’ winter grazing. She digs in the snow to see if there is ice in between or near the ground. Karen Anna also speaks with deep connection to her environment: the stars, the moon, the northern lights as they “danced above the trees.”

Indigenous people the world over tend to be the first to feel the effects of climate change. Because the Sámi people live with such direct dependence on the natural world they are dramatically affected by changes to the environment. As the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world, they are facing increased challenges to their reindeer husbandry, their survival, and way of life (The Environmental Justice Foundation 2019). A report by the Environmental Justice Foundation explains Arctic warming’s threat to the reindeer:

Unusually high temperatures above freezing are causing more frequent rain, which freezes on the ground into ice. Reindeer, trying to break through this ice layer to access the lichen, expend large amounts of energy which they can ill afford at this harsh time of year. Often, they fail entirely to break the ice, and starve to death. In 2013 alone, a total of 61,000 died as a result of these conditions in Arctic Russia. (The Environmental Justice Foundation 2019: 7).

The report also shares some accounts by Sámi reindeer herders about how these environmental changes directly impact their lives. Aslat Simma is one herder who shares the following:

What is different nowadays is that in short periods of time, you get very cold weather, and then within two hours you have very warm weather, and when it goes so fast- for the animals, the plants, nature – it’s very difficult to adapt to that. . . .

If I can’t live like this, then what do I do? I have to change my way of life. And if I change my way of life, the culture, and the way of doing things is going to change. It’s my job, but also my life (The Environmental Justice Foundation 2019: 4).

As you can imagine, the stress of these changes is taking a toll on the mental health of Sámi people. In Sweden, suicide rates in Sweden among the Sámi people can be up to four times higher than the national average. Sámi youth contemplate or attempt suicide at twice the rate than their Swedish peers (Schreiber 2016).

We can go further to understand the Sámi people’s experience with social change by listening to how they have been affected by natural resource exploitation in Sápmi. For decades the Sámi people have fought against encroachment by industries on their lands. Many herding districts have lost grazing land to industrial projects as well as roads, power grids, and housing. Watch this 2:05-minute video, “Indigenous activism in Sweden”, produced by Amnesty International, a human rights organization (figure 1.14). Maxida Märak, musician and activist, tells that part of the Sámi experience.

Figure 1.14. Indigenous activism in Sweden [YouTube Video]

The story of the Sámi, their deep connection and reliance to nature and reindeer is a powerful telling of how some communities experience social change acutely through the lens of environmental shifts. Looking further with an equity lens we can see how their experiences are exacerbated by the social changes of the larger global society and corresponding demands on their territory. In the case of the Sámi people, the environmental challenges combined with loss of land they are facing is directly threatening their way of life.

1.3.2 Social Change and a History of War: A Peace Community in Colombia

Figure set 1.15. Nine photos of members of the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó and other war resisters in Colombia. All photos by Aimee Samara Krouskop.

Another way to look at how different societies experience social change is by looking at major historical events that impact them the most. For example, armed conflict impacts communities deeply. The Peace Community of San San José de Apartadó in Colombia is a good example of how a history of war can shape a community’s experience with social change.

The Peace Community of San José de Apartadó is in the far-north and very remote regions of Colombia. Its original members (and in many cases their ancestors) have experienced displacement all their lives due to fifty years of violence and civil war within the country. In 1997, this group of small scale farmers from different villages signed a declaration to identify themselves as neutral among the armed actors of the conflict.

They rejected the presence of all armed groups in their territory, began refusing their demands to support them, and formed tight-knit working groups to more safely work in their fields. This was a brave and inspired pioneering initiative in a violently contested region of Colombia. See a slideshow of a few members of the Peace Community along with some collaborating war resisters via the clickable images in figure set 1.15.

Key to the Peace Community members’ safety after declaring neutrality was inviting international human rights protectors to support their endeavor. In 2004 they began to receive nearly around-the-clock accompaniment from human rights protectors who lived and traveled with them and provided support through diplomatic routes. Although displacement from some regions, killings by state police and military, stigmatization, and ongoing threats continue to this day, the Peace Community has managed to establish a certain deterrence against armed actors thanks to the recognition of their project at the international level. On March 23, 2022, the Community celebrated 25 years of peaceful resistance and it continues to be an inspiring alternative model of community life.

Imagine a lived experience like this; one in which it is necessary to apply all of your resources of resilience, and one in which you need to include international supporters so integrally into your community existence. How would that shape your lens of social change?

Chris Courtheyn, a former human rights protector who lived and worked with the Peace Community, describes how they integrate memories of their experiences into their social movement efforts. They devote considerable attention to commemorating massacres they’ve suffered and the members they’ve lost, mostly to military and paramilitary action. They install stones painted with victims’ names in a memorial area, and organize yearly pilgrimages to massacre sites (Courtheyn 2016). See images of a stone installation and a pilgrimage in figures 1.16 and 1.17.

Figure 1.16. Memorial stones built by the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó. From the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó’s web page.

Figure 1.17. Memorial pilgrimage of the Peace Community of San José de Apartado. From the Peace Brigades International website.

For this community, the history of severe violence and armed conflict dramatically shapes their experiences of social change. One common saying during community gatherings is: “We shape our future by recalling our past” (Krouskop 2006). They look to the past; to their memories of the people who they have lost during the war in order to imagine and organize for their future.

Courtheyn goes further to discuss how the Peace Community is also demonstrating an alternative way of responding to the violence perpetrated against their community. They avoid repeating the cycle of violence by setting aside vindictive action and replacing it with their commitment to their peace project. By building “…alternative, transformative and emancipatory politics through internal and external solidarity” (Courtheyn 2016:1).

1.3.3 Social Change and Culture: The Quechua and Aymara Worldview of Pachakuti

Figure 1.18. Image of Quechua dancer in Peru. Photo by Alphis Tay found on Flickr.

Figure 1.19. Image of Evo Morales (Aymara), first Indigenous President of South America. Photo by Sebastian Baryli found on Flickr.

Our final focus will explore how communities’ cultural worldviews shape their experience with social change. Worldview is a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world held by an individual or group.

The Aymara and Quechua Indigenous people have a unique perspective that combines their experience of social and environmental change. Quechua people primarily reside in Peru and parts of Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Ecuador (figure 1.18). The Aymara people primarily live in the central Andes in Peru and Bolivia; some also live in Argentina and Chile (figure 1.19).

While there exist many differences between the two cultures, they share a worldview called pachakuti. It’s a term that is difficult to translate to Western thought. Literally, it’s considered “the turning over of space-time” (Swinehart, 2019). But loosely, we can think of it as referring to times when social and environmental circumstances enter into a major change. Power and authority of established systems are undermined, dramatically transforming social relations and social order (Gutiérrez Aguilar 2014). Pachakuti can also be understood as a moment in which the world dies and is reborn anew (MacCormack 1988: 961; MacCormack 1993: 961 in Bria and Walter 2019).

Perhaps the closest term in the English language is “revolution” (Swinehart 2019). But imagine that revolution being both social and environmental. Another way to understand this concept is through the origins of pachakutis:

… (they) exist as myth (such as in creation stories about the formation of the Andean landscape when giants roamed and turned into mountains), but they also exemplify a deeply rooted social memory of the various epochs and ages of Andean history (separating the pre-Inka from Inka times, or the Inka from the Spanish colonial period) (Bria and Walter 2019: n.p.).

While Pachakuti describes the era during Spanish invasion and the demise of the Inca Empire, it has also been used to illustrate times marked by rebellions, both during colonial times and afterwards (Swinehart 2019).

Pachakuti also marks moments of environmental catastrophes and their aftermaths. Quechua communities are witnessing the disappearance of one of their most cherished elements of nature: the Andean glacial caps from which they receive essential water. From the perspective of pachakuti, the glaciers are seen as aging; heading toward a death and transformation, “…existing much like any other living thing in the world (Roncoli et al. 2001).”

During this era of profound social and environmental transformation Aymara and Quechua communities see the earth, as well as her inhabitants, as going through a time of transition from one cycle of time and order to another. That we are in the part of the cycle that creates destruction and chaos in order for a new world to begin.

1.3.4 Acknowledging Diverse Experiences with Social Change

The Sámi people of Sapmi, the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó, and members of the Quechua and Aymara communities each experience social change through a unique set of circumstances and worldviews. Some of those realities influence how communities experience social change more profoundly than others. For the Sámi people, we can see how shifting environmental realities threaten their way of life. For Peace Community members, their recent history of war encourages them to intimately incorporate memories of those they’ve lost. For Quechua and Aymara communities, their understanding of how the world changes in cycles and with transformation is inherent in their experience of social change.

1.3.5 Going Deeper

- For more information on Sapmi life watch this 7:35-minute video,“My Day with a Sami Reindeer Herder”

- To get a feel of the life of the Sami People during herding time, you can watch this visually stunning 3:17-minute video, “The Adrenaline Rush of Herding Reindeer”

- Read the full 2019 report by The Environmental Justice Foundation

- For more information on The San Jose de Apartadó Peace Community, watch this 11:49-minute video, “Protecting the Peace Pioneers”

- For more information on Pachakuti, watch this 1.5 hour documentary, PACHAKUTIQ – Time of Change – Documentary film – Naupany Puma

1.3.6 Licenses and Attributions for Diverse Experiences of Social Change

“Diverse Experiences of Social Change” by Aimee Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.11. A map showing the approximate distribution of the various Sami territories and language groups is found in the article, “Will the Sami Languages Disappear?” on the website of the Library of Congress and is public domain.

Figure 1.12. Clickable link to video of reindeer is found on Flickr by Karl Chan and is published with the NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) license.

Figure 1.13. Video: “People under the northern lights,

Figure 1.14. Video: “Indigenous activism in Sweden”

Figure set 1.15. “Peace Community of San José de Apartadó and San Francisco/Colombia” by Aimee Samara Krouskop CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Figure 1.16. Memorial stones built by the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó. From the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó’s web page.

Figure 1.17. Memorial pilgrimage of the Peace Community of San José de Apartado. From the Peace Brigades International website.

Figure 1.18. Image of Quechua dancer in Peru. Photo by Alphis Tay found on Flickr.

Figure 1.19. Image of Evo Morales (Aymara), first Indigenous President of South America. Photo by Sebastian Baryli found on Flickr.