2.5 Patterns and Process of Social Change

In Chapter 1 we referred to social change as the ways that human interactions, behavior patterns, and cultural norms change over time. Explained another way, social change is the change in society created through social movements as well as external factors. Essentially, any disruptive shift in the status quo, be it intentional or random, human-caused or natural, can lead to social change.

Here, we’ll focus on institutions, culture, technology, modernization, population, and social conflict as drivers of social change. Alone or in combination, these drivers can disturb, improve, disrupt, or otherwise influence society. When we look at social change through the lens of society’s components we can see reciprocal relationships. That is, each of these drivers of social change also are affected by social change in society.

2.5.1 Institutions as Drivers of Social Change

As we introduced above, a main framework developed by functionalists is the concept of institutions. Researcher and author, Jim Woodhill, describes social change as “ …a complex dynamic of social structure and individual action.” He adds that “ …Institutions essentially create incentives, both positive and negative, for individuals and groups to act in particular ways. People behave either to reinforce or undermine an institution.” (Woodhill 2008). When members of society determine that an institution no longer serves them well, they will undermine, or create shifts in that institution.

At the same time, each change in a single social institution leads to changes in all social institutions. For example, the industrialization of society meant that there was no longer a need for large families to produce enough manual labor to run a farm. Further, new job opportunities were in close proximity to urban centers where living space was at a premium. The result is that the average family size shrunk significantly. Larger families were no longer needed for the incentive of manual labor, so individual members began to shift the institution of family to smaller units (figures 2.27 and 2.28).

Figure 2.27 a painting by Théophile Deyrolle entitled The haymakers depicts a pre-industrial family harvesting.

Figure 2.28 an untitled painting ca. 1933-1943 that depicts a postindustrial family (artist unknown)

This same shift toward industrial corporate entities also changed the way we view government involvement in the private sector, created the global economy, provided new political platforms, and even spurred new religions and new forms of religious worship. It has also informed the way we educate our children.

Originally schools were set up to accommodate an agricultural calendar so children could be home to work the fields in the summer. Even today, teaching models are largely based on preparing students for industrial jobs, despite that being an outdated need. A shift in one area, such as industrialization, means an interconnected impact across social institutions. Several chapters of this book are structured around the study of institutions in relation to social change.

2.5.2 Culture and Technology

Culture and technology are other sources of social change. Changes in culture can change technology. Changes in technology can transform culture. Changes in both can alter other aspects of society (Crowley & Heyer 2011).

2.5.2.1 A complex relationship

Two examples from either end of the 20th century illustrate the complex relationship among culture, technology, and society. At the beginning of the century, the car was still a new invention. Automobiles slowly but surely grew in number, diversity, speed, and power. The car altered the social and physical landscape of the United States and other industrial nations as few other inventions have.

People built roads and highways. Pollution increased. Families began living farther from each other and from their workplaces. Tens of thousands of people started dying annually in car accidents. These are just a few of the effects the invention of the car had, but they illustrate how changes in technology can affect so many other aspects of society.

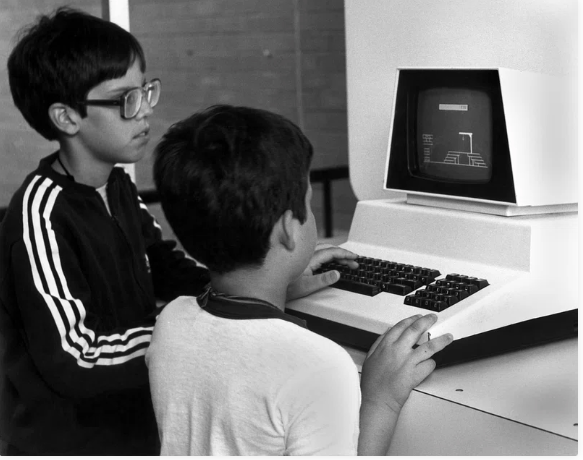

The development of the personal computer has also had an enormous impact. Anyone old enough, such as many of your older professors, remember having to type long manuscripts on a manual typewriter. They will easily attest to the difference computers have made for many aspects of our work lives.

Figure 2.29 An early personal computer, the Commodore PET

Figure 2.30 Now personal computers can weigh as little as two pounds and travel with us around the world.

E-mail, the Internet, and smartphones have enabled instant communication and make the world a very small place. Tens of millions of people now use Facebook and other social media. A generation ago, students studying abroad or people working in the Peace Corps overseas would send a letter back home, and it would take up to two weeks or more to arrive. It would take another week or two for them to hear back from their parents. Now even in poor parts of the world, access to computers and smartphones lets us communicate instantly with people across the planet.

As the world becomes a smaller place, it becomes possible for different cultures to have more contact with each other. This contact, too, leads to social change. Sometimes, one culture adopts some of the norms, values, and other aspects of another culture. This process has been happening for more than a century. The rise of newspapers, the development of trains and railroads, and the invention of the telegraph, telephone, and, later, radio and television allowed cultures in different parts of the world to communicate with each other in ways not previously possible. Affordable jet transportation, cell phones, the Internet, and other modern technology have taken such communication a gigantic step further.

2.5.2.2 Cultural Lag

An important aspect of social change is cultural lag, a term popularized by sociologist William F. Ogburn (1922/1966). When there is a change in one aspect of society or culture, this change often leads to and even forces a change in another aspect of society or culture. However, often some time lapses before the latter change occurs. Cultural lag refers to this delay between the initial social change and the resulting social change.

Discussions of examples of cultural lag often feature a technological change as the initial change. An example of cultural lag involves changes in child custody law brought about by changes in reproductive technology. Developments in reproductive technology have allowed same-sex couples to have children conceived from a donated egg and/or donated sperm (figure 2.31).

Figure 2.31. A couple in Thailand who used intravenous fertilization to conceive their baby.

If a same-sex couple later breaks up, it is not yet clear who should win custody of the couple’s child or children. Traditional custody law is based on the premise of a divorce of a married heterosexual couple who are both the biological parents of their children. Yet custody law is slowly evolving to recognize the parental rights of same-sex couples. Some cases from California illustrate this.

In 2005, the California Supreme Court issued rulings in several cases involving lesbian parents who ended their relationship. In determining custody and visitation rights and child support obligations, the court decided that the couples should be treated under the law as if they had been heterosexual parents. The court decided in favor of the partners who were seeking custody/visitation rights and child support.

More generally, the court granted same-sex parents all the legal rights and responsibilities of heterosexual parents. The change in marital law that is slowly occurring because of changes in reproductive technology is another example of cultural lag. As the legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights said of the California cases, “Same-sex couples are now able to procreate and have children, and the law has to catch up with that reality” (Paulson & Wood 2005: 1).

2.5.3 Modernization

Modernization is a complex set of changes that take place in societies that move from traditional to modern practices as their economies become industrialized. During this process societies create a greater variety of more specialized institutions. For example, as we mentioned above, the family has lost some of its functions due to the creation of other specialized institutions. Education and health systems for example, now serve purposes that families used to provide. The modernization process also involves an increase in a society’s specialization of labor.

Sociologists debate about whether the modernization process is positive or negative for a society. Proponents of modernization theory claim that modern states are wealthier and more powerful and that their citizens are freer to enjoy a higher standard of living. Modern societies are certainly a force for both good and bad in other ways. They have produced scientific discoveries that have saved lives, extended life spans, and made human existence much easier than imaginable in the distant past and even in the recent past.

But they have also required the destruction of indigenous cultures, polluted the environment, engaged in wars that have killed tens of millions, and built up nuclear arsenals that still threaten the planet. Modernization, then, is a double-edged sword. It has given us benefits too numerous to count, but it also has made human existence very precarious.We’ll discuss more about the modernization debate in Chapter 3.

2.5.4 Population Growth and Composition

Population composition is changing at every level of society. Births increase in one nation and decrease in another. Some families delay childbirth while others start bringing children into their folds early. Population changes can be due to random external forces, like an epidemic, or shifts in other social institutions, as described above. But regardless of why and how it happens, population trends have a tremendous interrelated impact on all other aspects of society.

In the United States, we are experiencing an increase in our senior population as Baby Boomers retire, which will in turn change the way many of our social institutions are organized. For example, there is a massive shift in the need for elder care and assisted living facilities, and growing incidence of elder abuse. Retiring Boomers may also lead to labor or expertise shortages, and healthcare costs will become a larger portion of our economy.

2.5.5 Social Conflict: War and Protest

Social change also results from social conflict, including wars, and ethnic conflict. The immediate impact that wars have on societies is obvious. For example, the deaths of countless numbers of soldiers and civilians over the ages have affected not only the lives of their loved ones but also the course of whole nations. To be more specific, the defeat of Germany in World War I led to a worsening economy during the next decade that in turn helped fuel the rise of Hitler.

One of the many sad truisms of war is that its impact on a society is greatest when the war takes place within the society’s boundaries. For example, the Iraq war that began in 2003 involved two countries more than any others: the United States and Iraq. Because it took place in Iraq, many more Iraqis than Americans died or were wounded. The war certainly affected Iraqi society—its infrastructure, economy, natural resources, and so forth—far more than it affected American society. Most Americans continued to live their normal lives, whereas most Iraqis had to struggle to survive the many ravages of war.

War can change a nation’s political and economic structures in obvious ways, as when the winning nation forces a new political system and leadership on the losing nation. For example, the deaths of so many soldiers during the American Civil War left many wives and mothers without their family’s major breadwinner. Their poverty forced many of these women to turn to prostitution to earn an income, resulting in a rise in prostitution after the war (Marks 1990).

In another example, the involvement of many African Americans in the U.S. armed forces during World War II helped begin the racial desegregation of the military (figure 2.32). This change is widely credited with helping spur the hopes of African Americans in the South that racial desegregation would someday occur in their hometowns (McKeeby 2008).

Figure 2.32 All African American 100th Pursuit Squadron, later designated a fighter squadron, was activated at Tuskegee Institute. The squadron served honorably in England and in other regions of the European continent during World War II.

2.5.6 Social Movements

Social movements are the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to achieve a social goal or address a social problem. These groups might be attempting to create change (such as Occupy Wall Street, or the Arab Spring), to resist change (such as the anti-globalization movement), or to provide a political voice to those otherwise disenfranchised (such as the civil rights movements). Social movements create social change.

While most of us learned about social movements in history classes, we tend to take for granted the fundamental changes they caused —and we may be completely unfamiliar with the trend toward global social movements. But from the anti-tobacco movement that has worked to outlaw smoking in public buildings and raise the cost of cigarettes, to uprisings throughout the Arab world, contemporary movements create social change on a global scale. We’ll discuss more about social movements in Chapter 9.

2.5.7 Licenses and Attributions for Patterns and Process of Social Change

“Patterns and Processes of Social Change” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0, with the following exceptions:

“Institutions as Drivers of Social Change” from “Reading: Social Change and Modernization” Lumens Learning, no author provided (This content is based partially on Soc 3e; check source in future edition)

Figure 2.27 a painting by Théophile Deyrolle entitled The haymakers depicts a pre-industrial family harvesting is in the public domain in WikimediaCommons.

Figure 2.28 an untitled painting ca. 1933-1943 that depicts a postindustrial family (artist unknown) is published by the Smithsonian under Open Access Media (CC0)

“Culture and Technology” is a remix of “20.2 Sources of Social Change, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA, and “Reading: Social Change and Modernization” Lumens Learning, no author provided (This content is based partially on Soc 3e; check source in future edition) Headings added and slight edits

Figure 2.29 An early personal computer, the Commodore PET by by Frank Hoffman is published byWikiwand and under Public Domain.

Figure 2.30 Now personal computers can weigh as little as two pounds and travel with us around the world is by Hernán Piñera and published on Flickr under (CC BY-SA 2.0)

“Cultural Lag” is from “20.2 Sources of Social Change, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA, minor edits for clarity

Figure 2.31. A couple in Thailand who used intravenous fertilization to conceive their baby is by Prachatai and published on Flickr under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

“Modernization” is adapted from “21.3 Social Change” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax Sociology 3e, licensed underCC BY 4.0. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/21-3-social-change definitions and subheadings added, edited for clarity and brevity.

“Population Growth and Composition” from “Reading: Social Change and Modernization” Lumens Learning, no author provided (This content is based partially on Soc 3e; check source in future edition) and “20.2 Sources of Social Change, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA, minor edits for clarity

“Social Conflict: War and Protest” is from “20.2 Sources of Social Change, no author provided, from Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World under CC BY-NC-SA, minor edits for clarity.

Figure 2.32 All African American 100th Pursuit Squadron is published by the U.S. National Park Service under public domain.

“Social Movements and Social Change” is from “Chapter 21 Social Movements and Social Change” in Introduction to Sociology: 1st Canadian Edition, William Little and Ron McGivern Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, reorganized and edited for brevity