5.3 Types of Economies

The two major economic systems in contemporary societies are capitalism and socialism. In practice, no one society is purely capitalist or socialist, so it is helpful to think of capitalism and socialism as lying on opposite ends of a continuum.

Capitalism, as introduced in the previous section, is an economic system in which the means of production are privately owned. By means of production, we mean everything—land, tools, technology, and so forth—that is needed to produce goods and services. Advocates of capitalism argue that this economic system enables individual freedom and that the desire for profit incentivizes innovation and economic prosperity.

Socialism, on the other hand, is an economic system in which the means of production are collectively owned, usually by the government. Whereas the United States has several airlines that are owned by for-profit airline corporations, a socialist society might have one publicly-owned and funded airline tasked with providing air travel to the population at little or no cost. Advocates for socialism argue that public ownership enables economic activity for the common good, not just the wealthy, thus providing a higher living standard for most people and a more stable economy.

Societies’ economies mix elements of both capitalism and socialism but do so in varying degrees. Some societies lean toward the capitalist end of the continuum, while other societies lean toward the socialist end. For example, the United States is a capitalist nation, but the government still regulates many industries to varying degrees and provides free public K-12 education. In another example, while China is formally Communist, its economy is better described as state managed capitalism, with a massive manufacturing industry catering to multinational corporations.

5.3.1 Sociological Perspectives on Economies

As an academic discipline, sociology emerged asking questions about why capitalism, and modern society more generally, emerged. Early sociologists also wanted to understand some of the consequences of capitalism on peoples’ lives. So, there are a huge number of thoughtful answers to those questions. We’ll focus on exploring the perspectives of two foundational thinkers within the discipline: Karl Marx and Max Weber.

5.3.1.1 Karl Marx

German philosopher and economist Karl Marx is famous as one of the key intellectuals of the communist movement and the lead author of the Communist Manifesto (Marx and Engels 1848). Whatever you think of his ideas, or his politics, he has arguably influenced the course of history as much as any other theorist in the last 200 years. For that reason alone, it is crucial to understand his ideas. Plus, they’re fascinating!

The most important thing to understand about Marx is that he’s a “materialist.” In social theory, materialism is a perspective that emphasizes the economy in explaining just about everything in society. For Marx, the economic system is the base, or foundation, of society. All other things are built on that foundation.

Marx believed that almost all economic systems (and most social structures) are rooted in class conflict. Class conflict refers to the structural antagonisms built into economic relationships. For example, the economic system of slavery in the United States was built on an exploitative conflict between two groups: the slave master and the slave. Enslaved people produced much of the wealth of the society by doing the labor. The master class took that wealth produced by enslaved people. In that sense, the master class is a non-productive consumer of the wealth produced by others (Marx 1976).

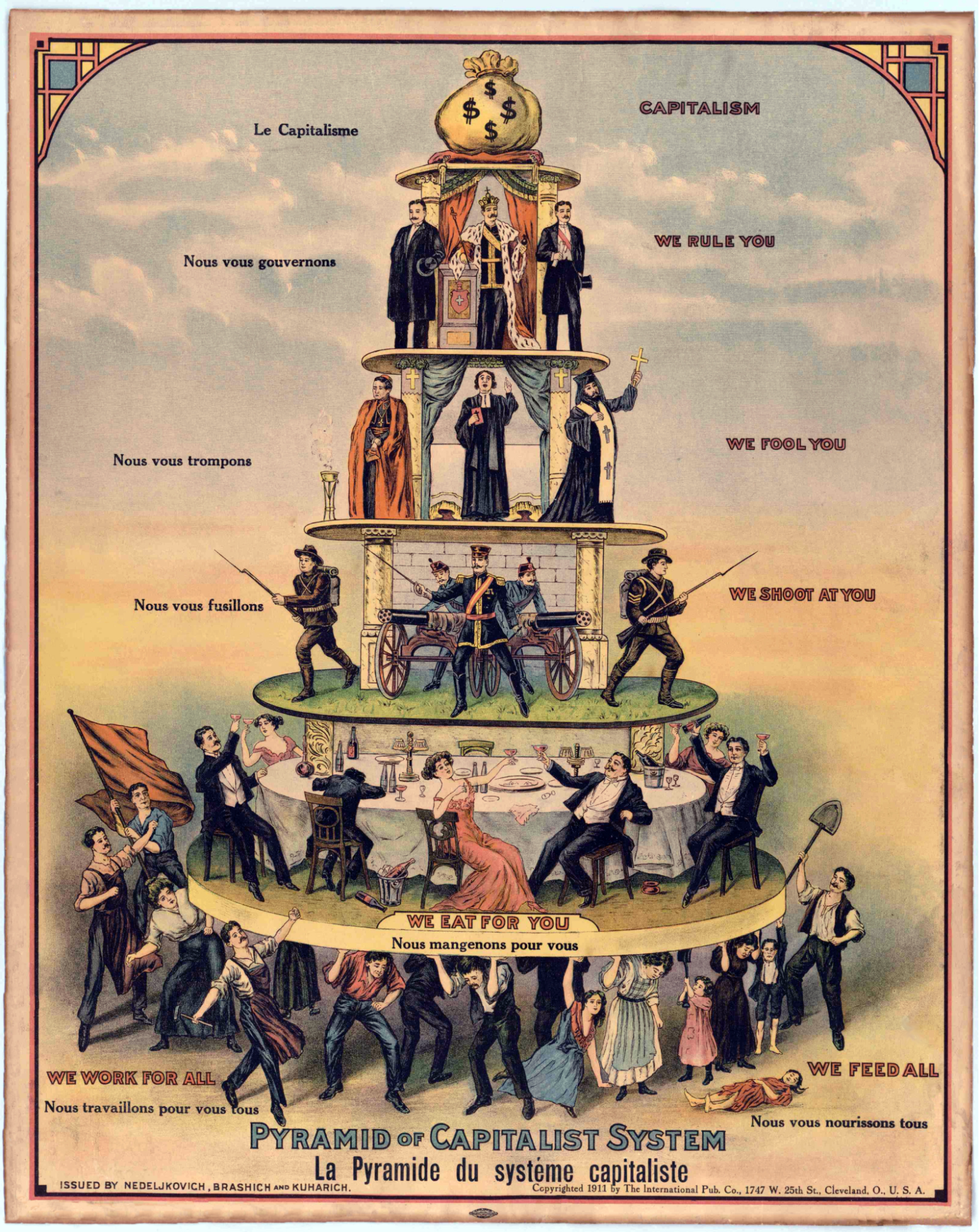

The important thing about this economic conflict, according to Marx, is that it is structural—it is built into the very fabric of the economy, as shown in figure 5.2 It isn’t just that the slave and master didn’t like each other. It is that the economic systems—the social structure itself—set them at odds. The only way to end that conflict is to abolish that economic structure and create a different kind of economy. This basic dynamic of conflict, says Marx, also operates in other economic systems, like feudalism, and even capitalism, our economic system.

Figure 5.2 This 1911 Anti-Capitalism poster represents a Marxist view of conflict and hierarchy within capitalism.

Marx suggests that class conflict is in fact the driving force of social change and progress. The everyday class conflict that is so central to the economy, he argues, will eventually erupt into open conflict, which will cause social change and will eventually result in the creation of a new economic system. This creates a kind of cycle of conflict, which pushes progress forward. Marx’s perspective on history and social change—this cycle caused by class conflict—is known as Historical Materialism. History, he says, is a series of class conflicts.

Marx argues that our economic system—capitalism—is governed by these same principles. Those who own the factories and businesses (the owning class, or bourgeoisie) use the labor of the working class (the proletariat) to produce wealth. And Marx argues that the owning class can only profit when they pay workers less than their actual value—that is, when they exploit them. The less the owners pay the workers, the more they keep in profits. For Marx, this conflict between workers and owners is the core of modern society. And like all economic conflicts, it will eventually erupt and cause social change.

Marx’s theories are influential today, not just because they illuminate important conflicts rooted in our own economic system and our social structure, but also because his emphasis on conflict has inspired many other theorists to explore power and inequality related to empire, race, gender and sexuality.

5.3.1.2 Max Weber

Max Weber was a German sociologist in the early 1900s. Like Marx, Weber was interested in the rise of capitalism. But unlike Marx, Weber highlighted the role of cultural beliefs in capitalism’s emergence.

Weber was especially interested in the role of changing religious beliefs within Christianity. He noted that the Protestant Reformation—a 16th century religious movement led by Martin Luther—changed the way many people thought about work and wealth. The Protestant Ethic is a set of cultural and religious beliefs that Weber argued laid the cultural groundwork for the rise of capitalism (Weber 1992).

So how did Protestant values enable the rise of capitalism? A big part of the answer has to do with how people thought about work.

Prior to the Protestant Reformation, most Europeans understood work in secular, or non-religious, terms. Sure, members of the Catholic clergy did sacred work, but everybody else did work that wasn’t steeped in religious meaning. If a person was a cobbler, they made shoes because they needed income, or because their father did it, or because they enjoyed the labor, but not because God wanted them to. That changed after the Protestant Reformation.

Weber points out that Protestantism extended “the calling” to all people, not just members of the clergy. A calling is a Christian concept for work that is assigned to a person by God and that provides meaning and purpose to a person’s life. That meant that God didn’t just call some people to the priesthood, He called all people to their labor. If a person was a cobbler, that was now their “calling.”

But why should that matter? Weber argued that in extending the calling, Protestantism imbued all labor with deep moral purpose. Now, one didn’t just make shoes because they needed to pay the rent. They made shoes as part of their sacred duty to God. Hard work, then, became a virtue, since it showed a person’s commitment to their calling. Even more, since Protestantism did not use the ritual of confession, hard work became a way for people to show their commitment to God and, perhaps, gain forgiveness for their sins. Hard work became the surrogate for confession (Allan 2007).

Protestantism also encouraged thrift and modesty, and discouraged the faithful from spending money on luxuries. So, if a person’s hard labor earned them profits, they should not spend those profits frivolously. Instead, they should reinvest their profits into the work to which God has called them.

So, in short, Protestantism redefined work, giving it a new moral weight. It also encouraged people to reinvest their profits into their work. Weber suggested that these new religious beliefs created fertile conditions for capitalism to develop (Allan 2007).

5.3.2 U.S. Economic Change: A Historical Perspective

Whatever the root causes of the rise of capitalism, it is clear that the capitalist economy has shaped the lives of the people who live within it. And as capitalism took on different forms within different time periods, lives changed. While economic inequality has been increasing in the U.S. for decades, it wasn’t always like this.

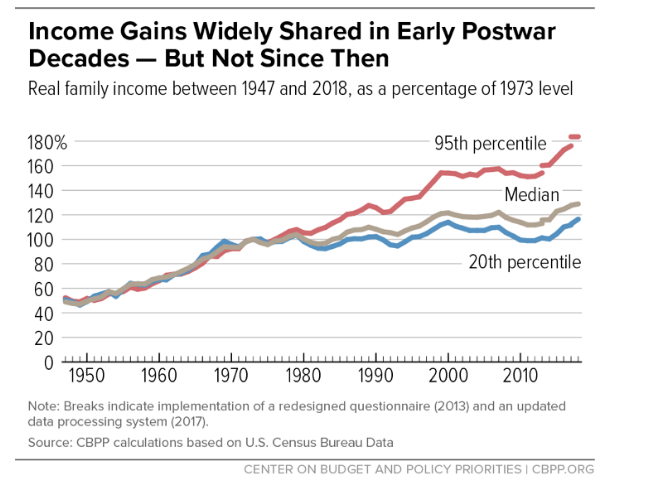

Figure 5.3 Income Inequality over time

From 1945 to 1975, income inequality was decreasing in the U.S. (Naoh 2013). In other words, the gap between the rich and the poor was shrinking (figure 5.3). This can be explained partly by the booming economy after World War II, but more importantly also by the rise of a strong labor movement. The labor movement increased wages, benefits and working conditions for most American workers, even those who weren’t unionized.

Declining inequality was also enabled by The New Deal, a series of government interventions in the economy passed during the Great Depression. The New Deal rapidly increased the number of well-paid government employees and put people to work building roads, bridges and other public works. It also created a social safety net, from social security to unemployment insurance and subsidized housing. Finally, after the catastrophe of the Great Depression, the government began to increase regulations on corporations and banks designed to protect the public interest (Noah 2013).

Inequality began to increase dramatically in the mid-1970s following a series of policy changes that began to reverse The New Deal (Noah 2013). Many conflict theorists argue that the economic and political transformations that began the early 1980s constitute an offensive of the owning class (specifically corporations) against the working classes. Following the election of Ronald Reagan in 1981, the federal government began adopting neoliberal economic policies.

Neoliberalism is an economic and political ideology emphasizing individual liberty and minimal government role in the economy. Confusingly, given its name, neoliberalism has been primarily advocated by the conservative and libertarian movements. However, it became so widespread that many liberal leaders (like Bill Clinton) also adopted it. Neoliberalism calls for cutting back social services, loosening regulations on corporations and banks, lowering taxes (especially the taxes on the rich), and opening international trade. Known as “trickle down” economics, these policies were passed in the name of boosting economic growth by making a more business-friendly environment.

The decreased taxation of business meant fewer dollars to fund government programs for the lower classes. At the same time, business was able to undermine the already faltering labor movement. The major industries in the U.S. economy, which tended to be strongly unionized, were increasingly automated and their production was moved offshore as business owners sought cheaper labor and looser regulations in the global south.

In a short period of time, the American economy transformed from a production economy to a service economy. Many working class jobs in the 1960s (at lumber mills, meat packing plants, auto factories, etc.) were unionized, and usually offered relatively high wages and benefits. One worker could support a family and perhaps buy a modest home. Today, most working class jobs are in the service sector (retail, food service, call centers, etc.) They pay minimum wage or slightly better, and offer minimal benefits. They tend to be part time and temporary, with limited opportunities for promotion.

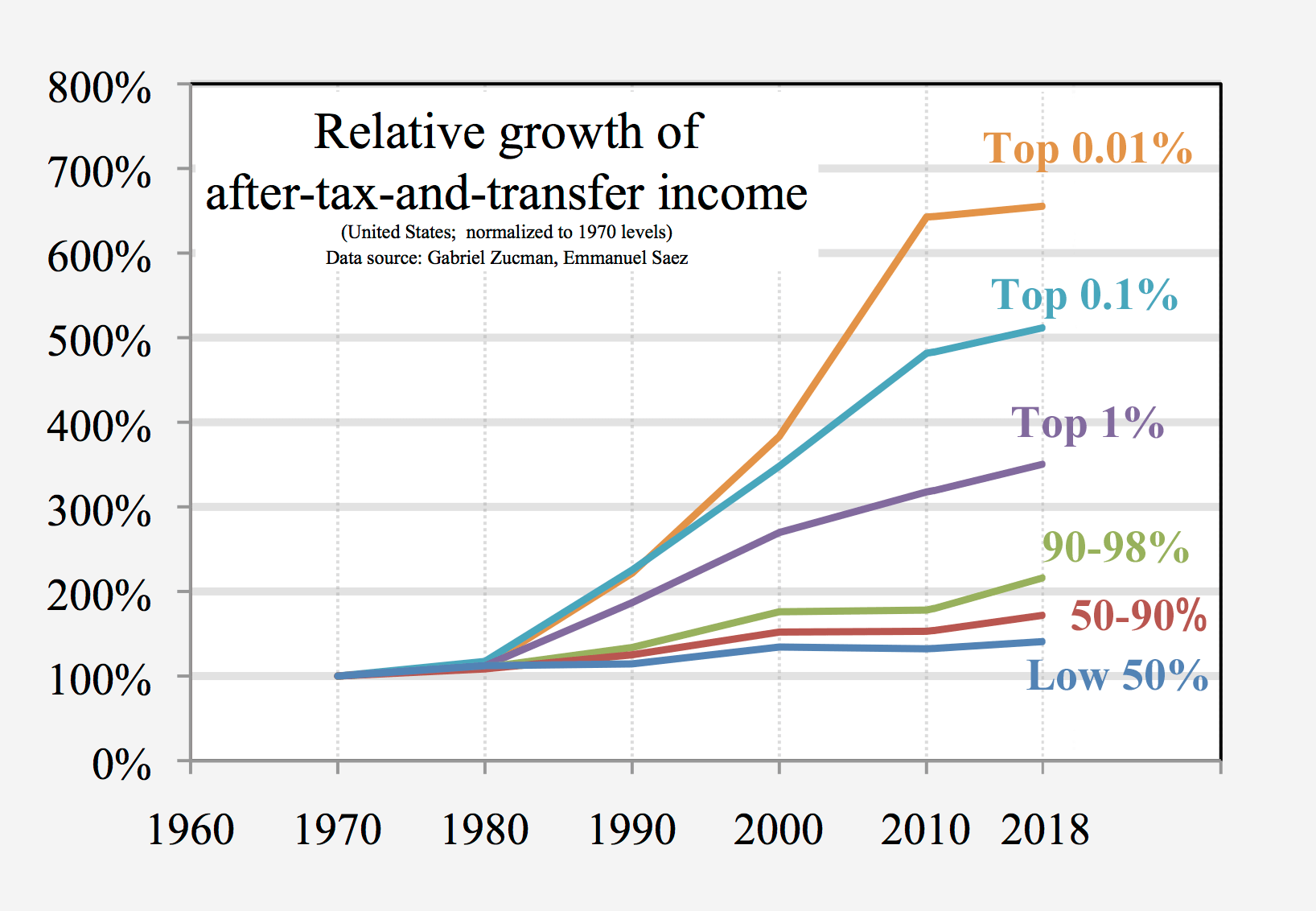

The effects of these economic changes have been striking. The rich have done marvelously well in the last few decades. They’ve seen their wealth and power increase markedly. However the poor, working classes and middle class have seen their wealth and income shrink or stagnate (Noah 2013). In the graph in figure 5.4 notice that since 1970, most income growth has gone to the most wealthy members of society: the wealthiest 1%, 0.1% and 0.01%. .

Figure 5.4 Relative growth of after-tax-and-transfer income.

5.3.3 Going Deeper

Check out this excellent 58-minute podcast, “Capitalism: What is it?”where three experts debate the merits of capitalism today. Keep these questions in mind as you listen:

- Do you notice any discrepancies between widespread cultural beliefs about the economy (like individual responsibility and economic opportunity) and economic realities?

- How do these different scholars understand the role of social forces in shaping an individual’s life experience?

- Given what you’ve read so far in this chapter, can you identify the theoretical perspectives of each scholar?

5.3.4 Licenses and Attributions for Types of Economies

“Types of Economies” by Ben Cushing is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The opening section of “Types of Economies” is adapted from “Types of Economic Systems” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by University of Minnesota, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Excerpted and edited for consistency.

Link title of source to: https://open.lib.umn.edu/sociology/chapter/13-2-types-of-economic-systems/

Link license to: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Figure 5.2 This 1911 Anti-Capitalism poster represents a Marxist view or conflict and hierarchy within capitalism. IWW – http://digital.library.pitt.edu/u/ulsmanuscripts/pdf/31735066248802.pdf, Pyramid of Capitalist System, issued by Nedeljkovich, Brashich, and Kuharich in 1911. Published by The International Pub. Co. , Cleveland OH. Original at File:Anti-capitalism color.jpg. Dust spots, stains, tears, and creases fixed through Gimp. Public Domain.

Figure 5.3 Income Inequality over time https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statistics-on-historical-trends-in-income-inequality (this is new)

Figure 5.4 old Relative growth of after-tax-and-transfer income. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1970-_Relative_income_growth_by_percentiles_-_US.png