5.6 New Economic Models

As Ben Cushing raises in the podcast, it’s crucial that we ask questions about any predictable outcomes that our economic order creates toward our ecological crisis. There is growing awareness that conventional economic models do not provide the necessary solutions to the challenges we are facing. We need to find new systems that can better address poverty, inequality, our financial crises, and climate change. These new systems must allow us to better engage with each other and the natural world. In response to this, alternative economic models are emerging. They are based upon placing real human and environmental needs at the forefront, and they honor diverse social values instead of just monetary ones. Let’s look at a few.

5.6.1 Re-evaluating Growth

Perhaps the basis for many of the new economic models we’ll discuss in this section is the perspective that economic growth needs to be re-evaluated. Economic growth refers to the inherent trait of the capitalist model that creates and requires ever-increasing production and consumption. Professor and author Susan Goldsworthy states that we are “obsessed by growth; it’s how we measure the success of organizations and of countries. And yet, it’s this very obsession that is accelerating our own demise.” (Goldsworthy 2022).

This re-evaluation of growth is not new. In Europe, in the late sixties and seventies, scholars debated the value of aiming for economic growth; an inherent part of our capitalist system. It wasn’t until 2002 that we saw protests related to concepts of degrowth beginning in 2002 (Duverger 2022). Proponents At the heart of this movement acknowledge that endless growth is not possible on a planet with finite resources. Growth is also seen as a phenomenon that promotes competition vs collaboration between people and prioritizes profits over people (Goldsworthy 2022).

Several initiatives sprung out of this movement. For example, voluntary simplicity is a lifestyle choice that minimizes the needless consumption of material goods and the pursuit of wealth for its own sake. Or neo-ruralism; the practice of migrants moving from cities to rural areas to live an agrarian lifestyle as a means of reducing consumerism, and transforming market relations, values and practices (Duverger 2022).

5.6.2 Localization

Localization is one of the movements that influence and shape new economic policies. Localization is a process of decentralization—shifting economic activity into the hands of millions of small- and medium-sized businesses instead of concentrating it in mega-corporations. Proponents of localization imagine a world where food comes from nearby farmers who ensure food security year round, and money we spend on everyday goods continues to recirculate in the local economy. Local businesses are able to provide enough meaningful employment opportunities for residents.

Localization is the basis from which new economic structures can evolve to allow the goods and services a community needs to be produced locally and regionally whenever possible. Instead of communities depending on distant, unaccountable corporations, they are able to be self-reliant. Localization is not imagined as total isolation. Products from surplus production are exported by communities once local needs are met, and goods that can’t be produced locally are imported. The free exchange of knowledge and ideas are still encouraged across borders, and global problems like climate change are still addressed globally.

5.6.3 The Economics of Happiness

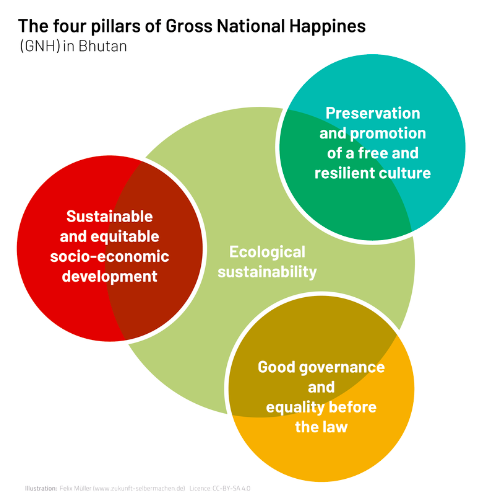

A few nations have adopted economic policies that pay attention to holistic social indicators, as was discussed in Chapter 3. For example, the United Kingdom and New Zealand have incorporated wellbeing goals into their priorities for assessing their nations’ economic health. The government of Bhutan however, prioritizes the philosophy of Gross National Happiness (GNH). GNH includes an index which is used to measure the collective happiness and well-being of a population. The index has four pillars: Preservation and Promotion of Culture, Sustainable and Equitable Social and Economic development, Conservation of Environment, and Good Governance and Equality Before the Law (figure 5.14).

Figure 5.14. The Four Pillars of Gross National Happiness in Bhutan

Within each of those pillars there are indicators of wellbeing that planners and policy makers can study. For example, Preservation and Promotion of Culture is in part measured by how many residents speak their native language. Sustainable and Equitable Social and Economic Development is in part measured by how many healthy days residents have in a year. Among other calculations, Conservation of Environment is measured by the level of responsibility that people take in caring for the environment.

Watch this 3:29-minute video (figure 5.15), What is “Gross National Happiness” ? As you watch, what comparisons can you make between the dominant economic system most of us live with, and the system established with Happiness priorities?

Figure 5.15. What is “Gross National Happiness” ? Explained by Morten Sondergaard [YouTube Video]

5.6.4 Doughnut Economics and Māori Worldview

Another alternative way of structuring our economic systems is with Doughnut Economics, an economic model that balances between essential human needs and planetary boundaries (figure 5.16). First published in 2012 by the economist Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics provides an alternative to the goal of GDP. It also is based on the principles of reevaluating growth.

It is a way to acknowledge real human and ecological needs into our economic systems. Key to this model is a visual depiction, with two concentric rings: a social foundation and an ecological ceiling.

The social foundation is framed to ensure that everyone receives life’s essentials. The ecological ceiling is designed to prevent humanity from using Earth’s life-supporting systems beyond healthy boundaries. The target spot for achieving this balance is in a doughnut-shaped space that sits between the two. The idea is: if a society can be managed within that doughnut space, it will be both ecologically safe and socially just (Doughnut Economics Action Lab n.d).

Figure 5.16. A visual framework of Doughnut Economics

Image description

Figure 5.16 shows the visual framework of Doughnut Economics. Note how this model acknowledges that economies, societies, and the natural world exist as complex, interdependent systems.

In Figure 5.17 please watch the 6:30-minute video, “How the Dutch are reshaping their post-pandemic economy”, narrated by originator of the concept, Kate Raworth. It explains how the Doughnut is applied and how planners in the city of Amsterdam have committed to using it as a model. Can you imagine applying the Doughnut to a place where you live? What would that look like?

Figure 5.17. How the Dutch are reshaping their post-pandemic economy – BBC REEL [YouTube Video]

A crucial element in any organizational model for societies is that it is designed with the perspectives and worldviews of those who reside within that society. For example, sustainability professional Juhi Shareef is an adopter of the Doughnut model. When she moved to New Zealand knew that she needed to partner with the people indigenous to that area if it was going to be a useful model. She explains that:

Working in sustainability, one understands that context is key. When we fail to identify or understand the nuanced, complex, systemic and local context of a situation, the best-intentioned solutions simply won’t solve society’s most pressing problems (Shareef 2020).

Shareef reached out to Teina Boasa-Dean, a member of Tūhoe Māori iwi. In this use, iwi means tribe in the language of Māoris. Shareef asked her help in understanding how the Doughnut model could be adapted to better reflect the worldview of the more than 775,000 Māori people who live in the country. Teina Boasa-Dean is an environmental scientist who works with both a technical perspective of the Tūhoes and an understanding of western science (Shareef 2020).

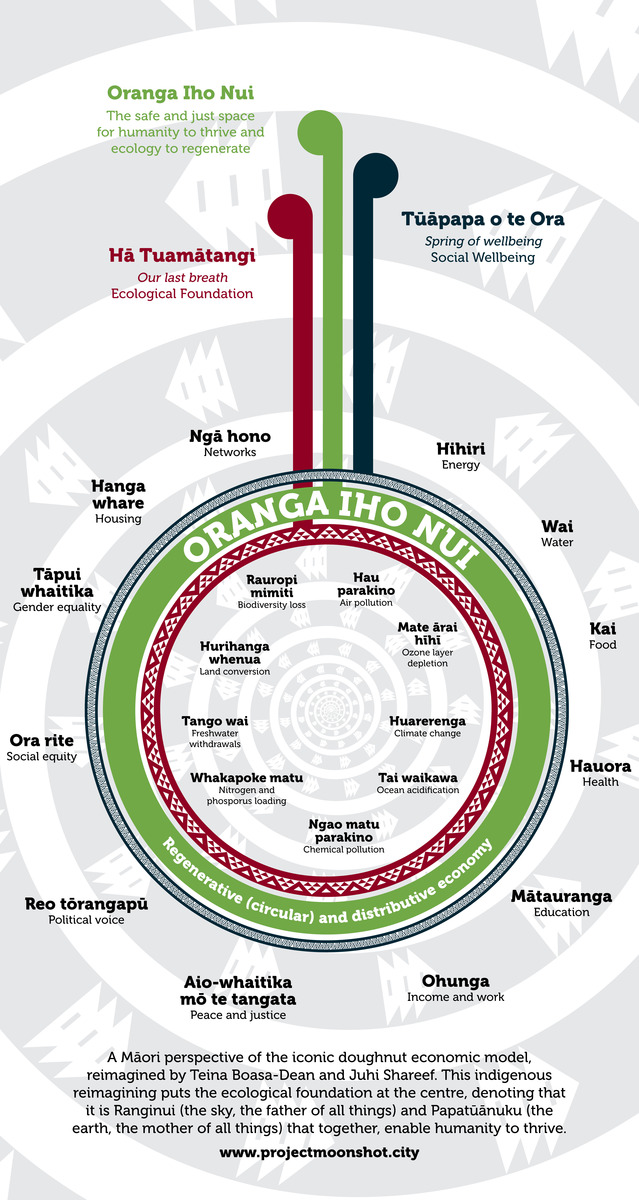

Take a look at the way that Teina Boasa-Dean reimagined the Doughnut in figure 5.18. How does it differ from the original Doughnut in figure 5.17?

Figure 5.18. A Tūhoe Māori perspective of the Doughnut economic model reimagined by Teina Boasa-Dean.

It is important to remember that Teina Boasa-Dean is a member of only one iwi, and over a hundred reside in New Zealand, each with unique cultural expressions. Thus, she can only speak to the cultural perspectives of the Tūhoe Māori. However, what she shares can serve to help us better understand communities who place nature at the center of existence.

What is most pronounced about Teina Boasa-Dean’s interpretation is that the environment sits in the middle of the doughnut, as its foundation. Social elements sit in the outer ring. This reflects Teina Boasa-Dean’s perspective that humans are dependent on the biosphere, and not the other way around (Shareef 2020). Teina Boasa-Dean spoke more about this perspective in a speech at the Circular Economy Pacific Summit in 2019:

… my own experiences of the land, the waterways, the winds, the sun, the moon and the stars have been guided and enhanced by the cosmological and pragmatic teachings of my elders. In turn their insights had been nurtured over thousands of years. I have been nurtured by these elders to understand a deep respect for mother nature and the myriad of rituals and [they have been] affirmed and reaffirmed my relationship.

I have been taught to leave offerings at the entranceway of forests of the mountain ranges and rivers and at ocean landmarks. I have also been taught to leave a new offering when I exit these natural paradises and each offering is couched inside a brief but relevant karakia or thanksgiving prayer. The offerings were often leaves or stones infused with prayer. It is a whole living system whether we know it or not. We are constantly re-humanized by this divine bond with nature and this is the relationship that was most valuable to my elders (Boasa-Dean 2019).

Teina Boasa-Dean’s perspective adds a crucial perspective to the Doughnut, and other new models in development: that economic systems should serve “…the management of people for the benefit of Whenua [earth] not the reverse.” (Boasa-Dean 2019).

5.6.5 Going Deeper

To better understand how economic growth is being reconsidered, watch the documentary, “Sustainable business, rethinking growth” produced by DW Documentary.

For more information on Bhutan’s Economics of Happiness, watch this 6:23-minute video, Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness or this 19:15 video, The Economics of Happiness (abridged version) – a short version of a film by the organization Local Futures.

For more on Doughnut Economics and the reevaluation of growth, watch this 15:53 minute Ted Talk video, A healthy economy should be designed to thrive, not grow.

To hear more about Teina Boasa-Dean’s perspective on Doughnut Economics based on Tūhoe Māori worldview, listen to the 22:50-minute podcast, “Episode 2 – Teina Boasa-Dean and a Maori interpretation of Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics”

5.6.6 Licenses and Attributions for New Economic Models

“New Economic Models” by Aimee Samara Krouskop is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.14. The Four Pillars of Gross National Happiness in Bhutan by Felix Mueller Wikipedia CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 5.15. Title of Video, “What is Gross National Happiness”?

Figure 5.16. A visual framework of Doughnut Economics https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Doughnut_(economic_model).jpg

Figure 5.17. “How the Dutch are reshaping their post-pandemic economy”

Figure 5.18 A Tūhoe Māori perspective of the Doughnut economic model reimagined by Teina Boasa-Dean is found at Doughnut Economics Action Lab and is licensed by DEAL – doughnuteconomics.org under CC BY SA 4.0.