6.3 The Reality of Institutions in the United States

While the previous section is meant to describe how these institutions theoretically work within the United States, this section is meant to illustrate the realities of such institutions and how they impact people within the U.S. We’ll explore the idea of health from multiple perspectives, explore the disparities in access to health and safety both internationally and nationally, and learn about instances in our society where these disparities have been prominent.

6.3.1 What is Health and Safety? Who Has Access to it?

Depending on who you talk to, health can be described in an infinite amount of ways. Health is the extent of a person’s physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (WHO 1946). This definition, taken from the World Health Organization’s treatment of health, emphasizes that health is a complex concept that involves not just the soundness of a person’s body but also the state of a person’s mind and the quality of the social environment in which they live. The quality of the social environment in turn can affect a person’s physical and mental health, underscoring the importance of social factors for these twin aspects of our overall well-being.

The degree to which we live healthy lives is directly related to how low the barriers are to access medical care for you and your loved ones, fresh and culturally relevant food, clean water, physical and mental stimulation, and connection to your surroundings and your communities. The degree to which we live safe lives is directly related to how stable our access is to reliable shelter, a secure home life, and care from community members and social services.

Re-read what was listed above and take note of what you currently have access to within your own life as well as what you don’t. Take another moment and survey internally how much each of those necessities currently cost. How much does it cost you annually to access all or some of these? What feelings come up when you are thinking about this?

If you felt anxiety, fear, sadness, or anger, you are unfortunately not alone. It is currently rare, both internationally and nationally, for people to have the ability to secure all of what is necessary to achieve a holistic state of health. This is due to systems in place that create inequality and disparities among us. While most of us have familiarity with these injustices, they often show up differently and at varying levels of severity depending on where we are located in the world.

6.3.1.1 Disparities in Health and Safety Internationally

The disparities between health and safety when we compare the international community versus the United States are stark. According to the World Health Organization:

There is ample evidence that social factors, including education, employment status, income level, gender and ethnicity have a marked influence on how healthy a person is. In all countries – whether low-, middle- or high-income – there are wide disparities in the health status of different social groups.

The lower an individual’s socio-economic position, the higher their risk of poor health. Health inequities are systematic differences in the health status of different population groups. These inequities have significant social and economic costs both to individuals and societies. (2018: n.p.)

As you read this chapter, it is important to keep in mind that the United States, as well as most Western European countries, are within the top 20% of wealthy countries in the world. As is the case nationally or locally, wealth inequality often leads to inequalities in terms of access to health and safety internationally. This is typically due to an inequitable and unequal distribution of resources.

The five countries with the lowest life expectancy in the world are all within the African continent. These countries are the Central Republic of Africa, Chad, Lesotho, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone. Within these countries, the average age of death for residents is 55 to 56 years old. Furthermore, “Children from the poorest 20% of households [worldwide] are nearly twice as likely to die before their fifth birthday as children in the richest 20% [of countries].”

Africa has seen extreme exploitation of both its people and natural resources– through slavery, genocide, and ongoing colonization, which we will discuss in depth later on– within the last several centuries across its continent. This has directly created the conditions that allow the premature death for many African people. (WHO 2018)

Looking at within-country inequality of nations lower on the global socioeconomic scale, we also see varying inequalities in access to healthcare– that is, access to medicine, emergency care, vaccines, and qualified doctors. This extends into the disparity seen in access to food and stability, with stability defined as the ability to live in adequate shelter and a safe environment. Nearly all of these countries that are lower on the global socioeconomic scale consist of people of the global majority. People of the global majority are Black, Indigenous, and other people of color and typically (though not all) have origins in Africa, Central and South America, and Asia. Policy, military force, and economic coercion have created these oppressive circumstances for people of the global majority.

6.3.1.2 Disparities in Health and Safety in the United States

While there are greater disparities between countries, the disparities in health and safety in communities within the United States is apparent. In the following sections, we will take a more in depth look at how racism, gender, and class influence the ability to attain health and safety within our country. Remember, health in this chapter is described as low barrier access to medical care for you and your loved ones, fresh and culturally relevant food, clean water, physical and mental stimulation, and connection to your surroundings and your communities. Safety, however, encompasses stability through reliable shelter, a secure home life, and care from community members and social services.

| This section contains intense topics that may be triggering or painful for some readers. Please be gentle with yourself as you read through this chapter and don’t hesitate to reach out to the counseling services in your community, at your college, or to your instructor if you need some support. |

6.3.1.3 The impact of racism on access to health

In this section, we will explore how racism impacts the ways in which people in the United States have access to water, connection to surroundings and communities, and care from community members and social services. Racism impacts much more than these aspects of health and safety. The consequences of racism affect every area of our lives. As you read, ask yourself: What experiences listed below remind me of crises of racism that my community or I have faced? How did we get through it? In what ways did we come together or implement creative solutions?

Figure 6.9 Racism seen as root of Jackson water crisis [YouTube Video]

Water is a necessity for survival. Its presence is something that is associated with growth, life and hygiene. Unfortunately, access to clean and safe water is not the reality most people in the world experience. This picture may be a scene that you associate with countries of the global majority. However, systemic racism in the U.S. created the ongoing water crisis in Jackson, Mississippi. Watch the 2:33-minute video “Racism seen as root of Jackson water crisis” for the story (figure 6.9). As you do, pay attention to how the student organizers explain the reasons for the water crisis in their city.

As discussed by Marccus Hendricks, an associate professor of Urban Studies at the University of Maryland, “The legacy of racial zoning, segregation, legalized redlining have ultimately led to the isolation, separation and sequestration of racial minorities into communities (with) diminished tax bases, which has had consequences for the built environment, including infrastructure.”(Costley & Pettus2022: n.p.)

While that article was written on September 16th, 2022, this water crisis has continued long past that date. Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color frequently experience a lack of updated and efficient infrastructure in the United States. This can leave whole cities scrambling for solutions.

Figure 6.10 A protest sign saying Stop Line 5/ Stop Line 3, crude oil pipelines located in Wisconsin, on the tribal territories of the Oma͞eqnomenew-ahkew (Menominee) Hoocąk (Ho-Chunk), and many other tribes.

As colonization persists and changes over the last five centuries, Indigenous communities everywhere struggle with loss of natural environment and culture. Because Indigenous identity is deeply connected to place and territory, displacement from ancestral land is detrimental to the health and safety of Indigenous communities.

First Nations in the U.S., such as the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe as well as many others, have been resisting a Canadian oil company named Enbridge for nearly two decades and continue to do so today (Stop Line 5 2022). Figure 6.10 shows one protest sign of many. Line 3 and Line 5 are both massive pipelines that have already endangered critical ecosystems and ways of life in Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, and Lake Heron. These pipelines break treaties between the U.S. government and tribes that are centuries old. They also endanger the wild rice, or manoomin, which is crucial for the health and spiritual identity of many Indigenous peoples of that area.

6.3.1.4 The impact of racism on access to safety

Feeling cared for, protected, and treated fairly by state-sponsored systems is a fundamental requirement for a healthy and safe life. Regrettably, rampant police brutality and state violence stemming from underlying racism in the United States often means that these needs are unable to be met for many people of color, especially Black or African Americans. State violence, much like racism, can be both overt and covert. An example of overt violence is state-sanctioned genocide. An example of covert state violence is there being a houseless population while there are empty homes.

The 2020 George Floyd uprisings were one of the largest nation-wide protests that the United States has experienced since its inception. The spark for this was the appalling murder of George Floyd, a Black man, in May of 2020. Police officers had apprehended him over what was allegedly the use of a $20 counterfeit bill. The protests continued well into the summer and, in some cities, throughout the year. (See the memorial to Mr. Floyd in figure 6.11.) The police brutality that Black and African Americans experience on a daily basis has been a consistent issue during and since the ending of slavery in the United States.

Figure 6.11 George Floyd Square, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Another area that impacts health and safety is in the U.S. incarceration system. The U.S. incarceration rate has grown considerably in the last hundred years. In 2008, more than 1 in 100 U.S. adults were in jail or prison, the highest benchmark in our nation’s history. And while the United States accounts for 5 percent of the global population, we have 25 percent of the world’s inmates, the largest number of prisoners in the world (Liptak 2008b).

The US incarceration system of today upholdsthe legacy of slavery. While Black people are only about 12% of the population in the United States, Black people make up almost 40% of people who are incarcerated (Federal Bureau of Prisons 2022). Additionally, the United States has the highest incarceration rates out of all Western countries.

By policing and imprisoning a significant portion of the population– a majority of whom are people of color– the incarceration system continues a legacy of exploitation and cheap or “free” labor. Watch this 2:33-minute video “Mass Incarceration, Visualized” in figure 6.12 for an insightful discussion on US incarceration rates, the inevitability of prison for certain demographics of young Black men and how it’s become a normal life event. What trends do you see in incarceration rates, and what consequences do you notice?

Figure 6.12 Mass Incarceration, Visualized [YouTube Video]

6.3.1.5 The impact of gender and sexual orientation discrimination on access to health and safety

Here, we will look in depth at how gender and sexual orientation discrimination creates disparity in access to medical and healthcare, and a secure homelife in this country. Like racism, gender discrimination is something that many of us face in our daily lives. It can be discreet or overt, embedded in policy or in cultural beliefs. Sometimes, it can be hard to identify and unlearn. Reflect on the examples below and identify how gender discrimination shows up in your daily lives or the lives of members of your community.

For centuries, the medical, healthcare and political structures within the United States have discriminated against those with varying gender and sexual orientations. The photo in figure 6.13.a depicts a protest led by the ACT UP! organization. ACT UP! continues to be a prominent voice in fighting the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It was one of the first organizations to bring the mistreatment of people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS to the national political stage.

In 1981, HIV/AIDS was declared a worldwide epidemic. This disease was incorrectly stereotyped to be a “homosexual” or “gay” disease, even though HIV/AIDS was and is diagnosed among people of all sexual orientations. This widespread fear, stigma, and ignorance resulted in the untimely death of over 100,000 people between 1981-1990 (CDC 1991).

Figure 6.13.a Image of a Protester:”HIV Criminalization is racist homophobia”

Figure 6.13.b Image of a protester. “Abortion is a human right”

The photo in figure 6.13.b is from a rally to defend Roe v Wade in 2022. In 1973, Roe v Wade was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that United States citizens had the right to have an abortion. In 2022, Roe v. Wade was overturned after a couple political changes: The Supreme Court became more conservative, and right-wing policymakers introduced a series of anti-abortion bills and initiatives.

As of November 2022, abortion is banned or restricted in Idaho, South Dakota, Wisconsin, Utah, Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Floria, Tennessee, North Carolina, Kentucky, and West Virgina (The New York Times 2022). Some of these bans make no allowance for people who may die during childbirth to obtain abortion. and most include the criminalization of those who seek out abortions or have miscarriages.

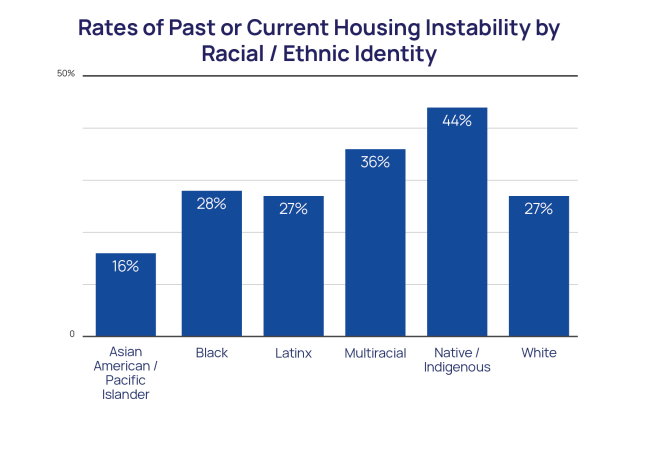

Another set of discriminations exist against people who identify as LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, or asexual). According to the Trevor Project as of 2022, 28% of LGBTQ youth in the United States have reported experiencing homelessness or housing instability at some point in their lives. You can see rates of housing instability for LGBTQIA youth, by race and ethnicity in figure 6.14.

Figure 6.14 Rates of Housing instability for LGBTQ youth, by race and ethnicity, from the Trevor Project

The website goes on to state that 44% of Native/Indigenous LGBTQ youth have experienced homelessness or housing instability at some point in their life, compared to 16% of Asian American/Pacific Islander youth, 27% of White LGBTQ youth, 27% of Latinx LGBTQ youth, 26% of Black LGBTQ youth, and 36% of multiracial LGBTQ youth. These rates are staggering and can have life threatening or deadly consequences considering. Statistics are often more severe for youth who identify as transgender. Watch the 2:23-minute film, “A Road To Home”. It’s a trailer for a documentary that follows the journeys of 6 LGBTQ homeless young people over 18 months (figure 6.15). What unique challenges do you notice the youth who are profiled in the video face?

Figure 6.15 A Road To Home – Trailer from Lumiere Productions on Vimeo.

6.3.1.6 The impact of class on access to health and safety

In Chapter 2 we introduced class as the set of people who share similar status based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and occupation. Your class can have a profound impact on your life. It allows or restricts the opportunities available to you. Class differences exacerbated by increasing systemic wealth inequality, has created massive disparities between people’s ability to access healthy and cultural foods, have adequate mental and physical stimulation, and acquire reliable shelter.

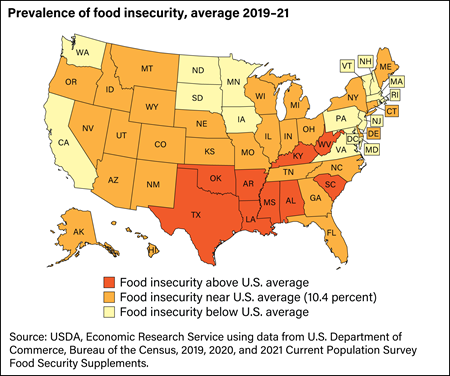

Figure 6.16 Map of Food Insecurity in the United States, average 2019-21

Image Description

The USDA states that currently 30% to 40% of food supply in the United States is wasted. At the same time, 32.1% of households with income levels below the poverty line experience food insecurity. See a breakdown of food insecurity by state in figure 6.16. Further, single parents, Black people, and Latino/a/x people experience food insecurity at substantially higher rates. That means that about 10% of all households currently experience food insecurity. What’s important to note here is that food security simply means access to food but does not include access to culturally relevant and healthy food. If we include this criteria in our ideas of health, then many families within the United States struggle obtaining true food security (USDA, 2015; USDA ERS, 2021; USDA ERS, 2021).

Figure 6.17 Image of man working late at night. Overwork is a systemic issue.

While mental and physical stimulation is a necessity for a well-rounded life, the United States currently has a problem with overworking. Overwork, defined as working to the point of health issues or even death, killed more than 745,000 people in the U.S. in 2021. Most of us are familiar with the terms “side hustle”, which means additional jobs, or “grind culture”, or working as much and as often as possible in an effort to become financially stable. These terms come from an underlying issue with our culture that forces us to work, even if it is unhealthy for us, for fear of being in poverty (figure 6.17).

NPR reports that, “Between 2000 and 2016, the number of deaths from heart disease due to working long hours increased by 42%, and from stroke by 19%,” the WHO said as it announced the study, which it conducted with the International Labour Organization.” (Chappell 2021)

Figure 6.18 Photo of a homeless veteran on the streets of Boston, MA

You may have heard the phrase, “housing is a human right”. This phrase holds truth – housing or shelter is not simply a commodity and is, in fact, a requirement to survive.

During the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many states mandated stay-at-home orders. But what happens when you do not have a home to shelter in place at, as shown in figure 6.18? The likelihood of becoming infected with COVID-19 was much higher than those who had secure shelter. Pandemic aside, people experiencing houselessness have lifespans that are shorter by about 17.5 years on average than that recorded for the general population in the United States (Perri et al. 2020).

6.3.2 Licenses and Attributions for The Reality of Institutions in the United States

The Reality of Institutions in the United States by Avery Temple is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 6.9 Title of Video: “Racism seen as root of Jackson water crisis”

Figure 6.10 A protest sign saying Stop Line 5/ Stop Line 3, crude oil pipelines in Wisconsin

Figure 6.11 George Floyd Square, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Figure 6.12 title of the Video “Mass Incarceration”

Figure 6.13.a Image of a Protester:”HIV Criminalization is racist homophobia”

Figure 6.13. b Image of a protester “Abortion is a human right”

Figure 6.14 Rates of Housing instability for LGBTQ youth, by race and ethnicity, from the Trevor Project

Figure 6.15 Title of Video: A Road To Home Documentary Trailer

Figure 6.16 Map of Food Insecurity in the United States, average 2019-21

Figure 6.17 Image of man working late at night. Overwork is a systemic issue.

Figure 6.18 Photo of a homeless veteran on the streets of Boston, MA