7.2 Education as a Social Institution

When you consider your COVID education story, it is likely that your education journey was interrupted in some way. You might have turned to YouTube to teach your second grader math. You might have needed a break and learned the latest dance step on Tik-Tok. All of us learn differently, and use many methods to figure things out.

The two minute video in figure 7.3 shows some of the ways that the Martu people of Australia hunt with fire. As you watch, please consider the following questions:

- Who is doing the hunting? Does this surprise you?

- What is the indigenous teaching around hunting and land stewardship?

- Using your imagination, how might this practice of hunting and stewardship be learned?

Figure 7.3. Fire Hunting in Australia [YouTube Video] (time: 2:01).

Traditionally, learning involves storytelling and practice. For the Martu people in Australia, the practices of hunting are taught by stories and experience. In this video, we see hunting practices using fire practiced by women who are hunting monitor lizards (figure 7.3). The women use controlled burns to catch and kill the lizards. In addition, the fire itself makes the landscape more useful for lizard habitat.

As a young person, you might learn about hunting by listening to the stories the hunters tell about the hunt that happened today. Or you might help skin the animals once they were caught. Today, the Martu also have access to schools, and can learn to read and write (Scelza n.d.), in addition to learning through lived experience..

When sociologists look at learning they are more likely to focus on the institution and inequality, in addition to interactions that may happen in the classroom. In this basic sociological definition education is a social institution through which members of a society are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms (Conerly et al. 2021). In this view, students learn not just reading and writing, but how to follow directions, and how to participate in social activities, even things as simple as standing in line.

As we’ve seen in other chapters in this book, education can be a driver of social change and a means of maintaining a status quo that does not serve everyone well. On one hand, education can be a cause of social change. For example, teaching girls to read and write is a component in decreasing poverty in many countries. In other circumstances education serves to reproduce structures of inequality. In the United States, families who are poor receive less access to quality education. How then are we to make sense of this complicated social institution?

7.2.1 Education and the Rise of Democracy

When we think about education as an institution, we consider the function that it serves in our society. According to the U.S. founding fathers, education served the function of creating responsible citizens. Like other revolutionaries of the time, they argued that if people could read and write, they could also decide for themselves. This idea of government serving at the will of the people, which was revolutionary at the time, depended on the people to make informed choices. In other words,

For America’s founders, public education was essential to keeping the republic. Thomas Jefferson famously proclaimed that of all the arguments for education, “none is more important, none more legitimate, than that of rendering the people safe, as they are the ultimate guardians of their own liberty.” (Neem 2019)

Creating a system of formal public education also served the function of stabilizing a new nation. During the colonial period, the Puritans in what is now Massachusetts required parents to teach their children to read and also required larger towns to have an elementary school, where children learned reading, writing, and religion. In general, though, schooling was not required in the colonies, and only about 10 percent of colonial children, usually just the wealthiest, went to school, although others became apprentices (Urban and Wagoner 2008).

To help unify the nation after the Revolutionary War, textbooks were written to standardize spelling and pronunciation and to instill patriotism and religious beliefs in students. At the same time, these textbooks included negative stereotypes of Native Americans and certain immigrant groups. The children going to school continued primarily to be those from wealthy families. By the mid-1800s, a call for free, compulsory education had begun, and compulsory education became widespread by the end of the century. This was an important development, as children from all social classes could now receive a free, formal education. Compulsory education was intended to further national unity and to teach immigrants “American” values. It also arose because of industrialization, as an industrial economy demanded reading, writing, and math skills much more than an agricultural economy had.

Free, compulsory education, of course, applied only to primary and secondary schools. Until the mid-1900s, very few people went to college, and those who did typically came from fairly wealthy families. After World War II, however, college enrollments soared, and today more people are attending college than ever before, even though college attendance is still related to social class, as we shall discuss later in this chapter.

An important theme emerges from this brief history: Until very recently in the record of history, formal schooling was restricted to wealthy males. This means that boys who were not White and rich were excluded from formal schooling, as were virtually all girls, whose education was supposed to take place informally at home. Today, as we will see, race, ethnicity, social class, and, to some extent, gender continue to affect both educational achievement and the amount of learning occurring in schools.

7.2.2 Pierrre Bourdieu: The Reproduction of Economic Inequality through Cultural and Social Capital

Functionalist sociologists focus on the purpose that education serves. As we learned in the last section, literacy can support democracy. Conflict sociologists, on the other hand, look at what maintains unequal social power. They particularly use social class as part of their analysis.

When we apply this lens to education, we see that the fulfillment of one’s education is closely linked to social class. Students of low socioeconomic status are generally not afforded the same opportunities as students of higher status, no matter how great their academic ability or desire to learn. Picture a student from a working-class home who wants to do well in school. On a Monday, he’s assigned a paper that’s due Friday. Monday evening, he has to babysit his younger sister while his divorced mother works. Tuesday and Wednesday, he works stocking shelves after school until 10:00 p.m. By Thursday, the only day he might have available to work on that assignment, he’s so exhausted he can’t bring himself to start the paper. His mother, though she’d like to help him, is so tired herself that she isn’t able to give him the encouragement or support he needs. And since English is her second language, she has difficulty with some of his educational materials. They also lack a computer and printer at home, which most of his classmates have, so they have to rely on the public library or school system for access to technology. As this story shows, many students from working-class families have to contend with helping out at home, contributing financially to the family, poor study environments and a lack of support from their families. This is a difficult match with education systems that adhere to a traditional curriculum that is more easily understood and completed by students of higher social classes.

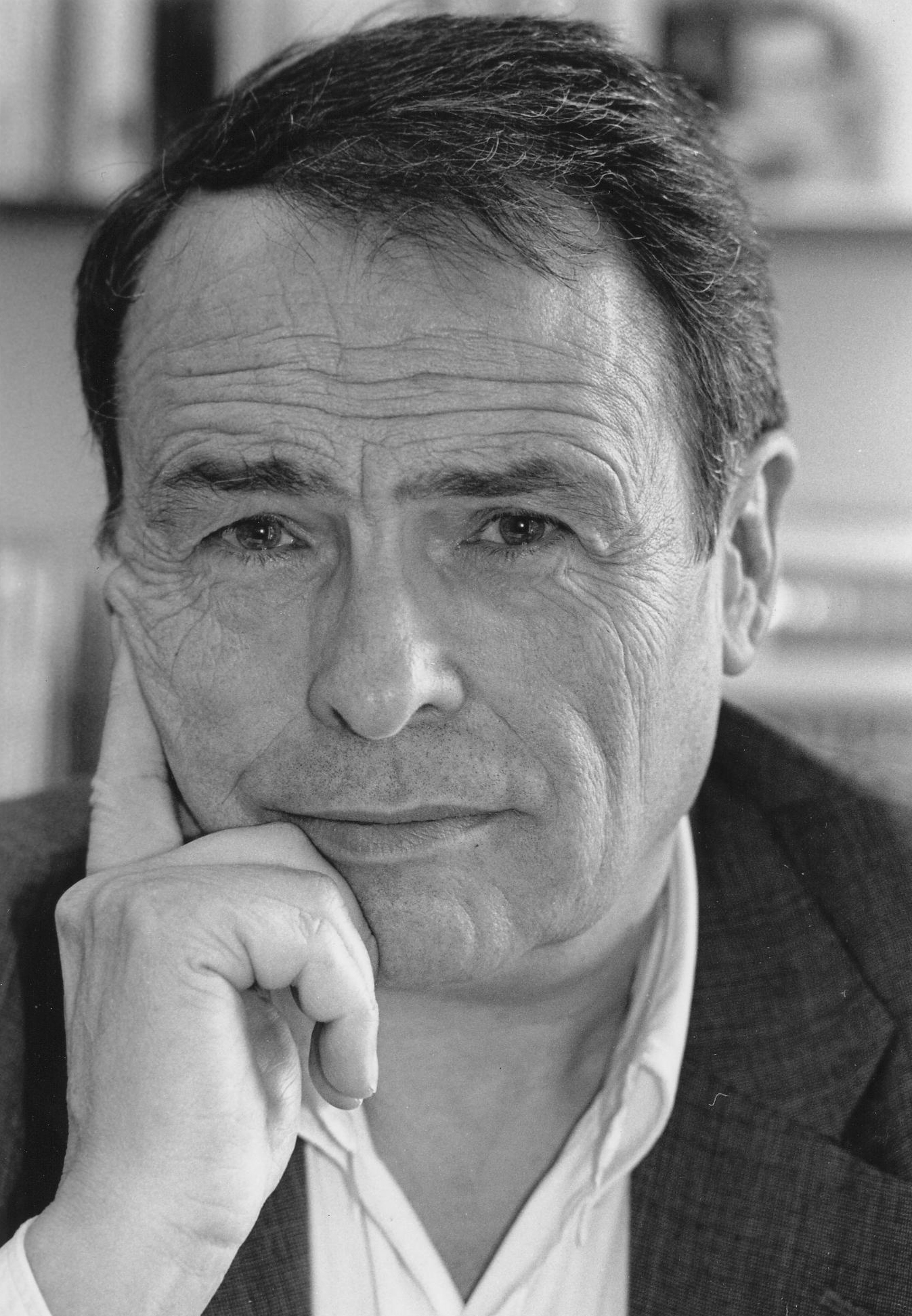

Figure 7.4. Photo of Pierre Bourdieu

Such a situation leads to maintaining social class across generations, extensively studied by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (figure 7.4). He researched how cultural capital, or cultural knowledge that serves (metaphorically) as currency that helps us navigate a culture, alters the experiences and opportunities available to French students from different social classes. His results from France have been applied also to students in other countries. Members of the upper and middle classes have more cultural capital than do families of lower-class status. As a result, the educational system maintains a cycle in which the dominant culture’s values are rewarded. Instruction and tests cater to the dominant culture and leave others struggling to identify with values and competencies outside their social class. For example, there has been a great deal of discussion over what standardized tests such as the SAT really measure. Many argue that the tests group students by cultural ability rather than by natural intelligence.

The cycle of rewarding those who possess cultural capital is found in formal educational curricula as well as in the hidden curriculum, which refers to the type of nonacademic knowledge that students learn through informal learning and cultural transmission. This hidden curriculum reinforces the positions of those with higher cultural capital and serves to bestow status unequally.

Conflict theorists point to tracking, a formalized sorting system that places students on “tracks” (advanced versus low achievers) that perpetuate inequalities. While educators may believe that students do better in tracked classes because they are with students of similar ability and may have access to more individual attention from teachers, conflict theorists feel that tracking leads to self-fulfilling prophecies in which students live up (or down) to teacher and societal expectations (Education Week 2004).

To conflict theorists, schools play the role of training working-class students to accept and retain their position as lower members of society. They argue that this role is fulfilled through the disparity of resources available to students in richer and poorer neighborhoods as well as through testing (Lauen and Tyson 2008).

IQ tests have been attacked for being biased—for testing cultural knowledge rather than actual intelligence. For example, a test item may ask students what instruments belong in an orchestra. To correctly answer this question requires certain cultural knowledge—knowledge most often held by more affluent people who typically have more exposure to orchestral music. Though experts in testing claim that bias has been eliminated from tests, conflict theorists maintain that this is impossible. These tests, to conflict theorists, are another way in which education does not provide opportunities, but instead maintains an established configuration of power.

7.2.3 Violence and Oppression: Indian Residential Schools

As you might remember from Chapter 1, though, we need to employ a more powerful equity lens to explore the institution of education. Already we see that even though our early politicians agreed that education was a requirement for country-building, many people were excluded. We notice that the institution serves the function of maintaining existing social classes. As we use our equity lens more powerfully, we see that the institution of education sometimes supports violent and oppressive social change. For this, we look at the history of boarding schools for Indigenous peoples in the United States and Canada, once described by the governments that funded them as Indian Residential Schools .

By establishing boarding schools for Indigenous children, colonizers committed genocide, the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group. This is a strong claim, so let’s look at the evidence. In May 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. The report details some of the basic facts. The United States established 408 Federal Indian Boarding Schools run between 1891 and 1969. Congress established laws which required Indian parents to send their children to these boarding schools (Newland 2022: 35). The explicit intention of the schools was to disrupt the families and the cultures of Indigenous people. Government records document, “[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022: 38). Because students were required to learn English and agriculture and punished if they spoke their Indigenous languages and practiced their own religious and spiritual practices, families and cultures were indeed destroyed.

Figure 7.5. Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior, first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary.

Deb Haaland (figure 7.5), the U.S. Secretary of the Interior and a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, describes this history in the following way:

>Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of indigenous children were taken from their communities. (Haaland 2021)

Secretary Haaland also recounts the suffering in her own family. She writes: “My great grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Its founder coined the phrase ‘kill the Indian, and save the man,’ which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time” (Haaland 2021). The 2022 U.S. Federal report documents at least 500 deaths of children buried in 53 burial sites (Newland 2022:8). However, they caution that the work of finding and identifying the remains of the children has been limited due to COVID-19. They anticipate finding even more evidence of death. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6000 First Nations children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021).

Figure 7.6. Photo of the Chemawa Indian School, Salem Oregon, no date.

The U.S. government forced hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children to attend Indian Residential Schools (National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition n.d.). Oregon shares this painful history. Historian Eva Guggemos and volunteer historian SuAnn Reddick from Pacific University combed the historical record for the Forest Grove Indian Training School in Forest Grove, which became the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon (figure 7.6). They found that at least 270 children had died while at these schools. Most of these deaths were due to infectious diseases.

Even in cases where the children didn’t die, colonizers accomplished cultural hegemony, achieving authority, dominance, and influence of one group, nation, or society over another group, nation, or society; typically through cultural, economic, or political means. In this case, the colonizers valued their own White, European culture, and forced other groups to conform. These pictures in figure 7.7 and 7.8 tell a story of change and assimilation.

Figure 7.7. Caption from website: A group portrait of students from the Spokane tribe at the Forest Grove Indian Training School, taken when they were “new recruits.”

Figure 7.8 Caption from Website: Seven months later — the students pictured are probably the Spokane students who, according to the school roster, arrived in July 1881: Alice L. Williams, Florence Hayes, Suzette (or Susan) Secup, Julia Jopps, Louise Isaacs, Martha Lot, Eunice Madge James, James George, Ben Secup, Frank Rice, and Garfield Hayes.

In the Pacific University magazine, Mike Francis writes about these photos in more detail:

A particularly poignant pair of photos in the Pacific University Archives vividly show what it meant for native youths to leave their families to come to Forest Grove. An 1881 photo of new arrivals from the Spokane tribe shows 11 awkwardly grouped young people, huddled together as if for protection in an unfamiliar place. Some have long braids of dark hair; some girls wear blankets over their shoulders; some display personal flourishes, including beads, a hat, a neckerchief.

A second photo of the group is purported to have been taken seven months later, after the Spokane children had lived and worked for a time at the Indian Training School. In this photo, the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck.

Further, one girl is missing in the second photo — one of the children who died after being brought to Forest Grove, said Pacific University Archivist Eva Guggemos, who has extensively studied the history of the Indian Training School. The girl’s name was Martha Lot, and she was about 10 years old. Surviving records tell us she had been sick for a while with “a sore” on her side and then took a sudden turn for the worse.

The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad — frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of indigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures. (Francis 2019)

The function of education in the case of Indian Boarding Schools doesn’t stop with cultural assimilation. Education functioned to purposefully disrupt families and cultures. Beyond that, the government policies and practices related to Indian education were part of a wider strategy of land acquisition. As early as 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that discouraging the traditional hunting and gathering practices of the Indigenous people would make land available for colonists. This is a concrete example of land grabbing, a practice you learned about in Chapter 4. Jefferson wrote,

>To encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms and of increasing their domestic comforts (Jefferson 1803, quoted in Newland 2022:21).

By removing people from the land, and children from families, the US Government made the land available to colonists, who were mainly from Europe, an indirect but purposeful function of education.

7.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Education as a Social Institution

“Education as a Social Institution” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Education and the Rise of Democracy, partially based on Social Problems Continuity and Change – An Overview of Education https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_social-problems-continuity-and-change/s14-01-an-overview-of-education-in-th.html University of Minnesota Licenced under Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 lightly edited

Pierre Bourdeau: Credentialism/Cultural Capital

Introduction to Sociology 3e – Theoretical Perspectives on Education

CC-BY 4.0 lightly edited

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/16-2-theoretical-perspectives-on-education

Figure 7.3. Figure Hunting In Australia. https://youtu.be/j8zb44roDTM

Figure 7.4. Pierre Bourdieu Bernard Lambert, own work, CC-BY-SA 4.0 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Bourdieu#/media/File:Pierre_Bourdieu_(1).jpg

Figure 7.5. Deb Haaland U.S. Secretary of the Interior https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Deb_Haaland_official_portrait,_116th_congress_2.jpg U.S. House Office of Photography 2019 Public Domain

Figure 7.6. Chemawa Indian School https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/or0051.photos.130102p/resource/ Public Domain

Figure 7.7.https://www.pacificu.edu/magazine/tragic-collision-cultures Public Domain

Figure 7.8. .https://www.pacificu.edu/magazine/tragic-collision-cultures Public Domain