7.5 Education and Social Change

When we examine how students perform in school—how many grades students attend school; whether they can read, write, reason critically, or use computers; whether they graduate from high school or end up at NASA or being brain surgeons—we see a difference between wealthy, White, male students and those who are not. The achievement gap refers to any significant and persistent disparity in academic performance or educational attainment between different groups of students, such as White students and students of Color, for example, or students from higher-income and lower-income households (Great Schools Partnership n.d.). Most recently, the achievement gap between women and men appears to be closing. Colleges and universities in the US are enrolling as many women as men, and more women than men appear to be graduating.

However, differences in educational outcomes persist when you examine the trends using race and class. When layers of marginalized social locations are added, like with students who are poor and Black or Brown in the previous section, the differences in outcomes become even more pronounced. To explain this, we examine the history of who is educated over time, how educational policy has expanded access to education (somewhat) and the tension between universal education and separate space.

Let’s start with changes in laws and policies.

7.5.1 Social Change in Education through Law

7.5.1.1 Legal Segregation

As we discussed earlier in this chapter, education for the “common man” was a core principle in establishing democracies in the late 1700s and early 1800s. However, throughout history and this chapter, we notice that we haven’t yet achieved universal access to education, people’s equal ability to participate in an education system. Early education systems in the United States were segregated. Segregation refers to the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions. Schools were segregated by gender, race, ability/disability, and class. Educator and researcher Gloria Ladson-Billings summarizes the history of segregation in education in the United States. She writes:

In the case of African Americans, education was initially forbidden during the period of enslavement. After emancipation, we saw the development of freedmen’s schools whose purpose was the maintenance of the servant class. During the long period of legal apartheid, African Americans attended schools where they received cast off textbooks and materials from White schools…. Black students in the south did not receive universal secondary education until 1968.” (2006:5, italics added)

To the extent that higher education was possible for Black students, it was in historically Black universities and colleges, because admission was not possible in White universities.

As we discussed in the section on Violence and Oppression: Indian Residential Schools, Indigenous children were educated in residential schools which emphasized obedience and forced acculturation to White European culture. At these schools, it was illegal for Native American children to be taught in their own languages. The federal government established boarding schools for Indigenous children. The children were separated from their families so that they could become “American”—that is to say, speak English, dress in European clothes, and become Christian. In higher education, Indigenous students were only welcome at some historically black colleges and universities.

Even when education was legal for many marginalized groups, it was provided in separate, segregated facilities that often (but not always) provided lower-quality education. This history of inequality is the deep roots of unequal outcomes in education.

7.5.1.2 Legal Integration

The state-sponsored racial segregation of public schools and other public spaces became illegal with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). This change in federal law launched passionate and often violent conflicts to integrate schools.

Figure 7.16. Button from Washington DC Freedom March

Since 1954, many laws that move from segregated to integrated education have been passed. In 1964 Congress passed the Civil Rights Act which prohibited discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity, and national origin particularly applied to voting rights and public accommodations, Title IV prohibits segregation in schools. Title VI of this act prohibits discrimination based on race, color, ethnicity and national origin for any programs that receive federal funds, including schools and colleges. The educators at Learning for Justice describe Title VI as “one of the biggest victories of the civil rights movement” (Collins 2019). These legal changes were the result of fierce activism by Black, Brown, and White people. You can see a button from the related Freedom March in figure 7.16.

In separate legislation, Title IX (nine) of the Education Amendments of 1972 stated:

No person in the United States shall, based on sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance. (United States 1972)

Title IX opened the doors of education even wider to women, because colleges could no longer use gender as a reason to admit or fail to admit students. It also resulted in funding for women, and for women’s sports. More recently, this amendment has been used to protect LGBTQIA+ students from discrimination in public and private schools, at least legally.

In the decades after Brown vs the Board of Education, we see Integration as step 4 in the process of a social problem. The government in the form of the legislature and US Supreme Court creates and uphold laws which expand access to education. Although we fall short of equal outcomes, according to the law, people of all races, ethnicities, class, genders, and ages can learn together.

7.5.1.3 De-facto Segregation

However, changes in federal and state laws are only one step in the process of creating social change. Educational segregation is illegal, but many of our classrooms are still segregated.

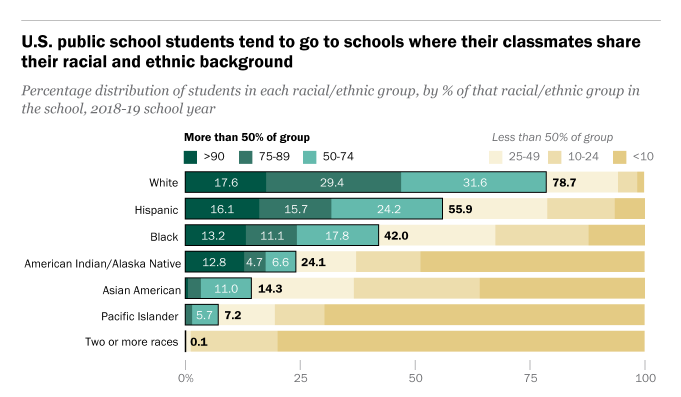

Figure 7.17 Schools are still segregated.

In a recent analysis of U.S. Department of Education data, Pew Research reports that most students attend schools that serve other students of their race and ethnicity (figure 7.17). In other words, White students are likely to attend schools where half or more of the other students are also White. Hispanic students are also likely to attend schools where at least half of the other students are also Hispanic. For other racial groups, the proportions are slightly smaller, partially because the numbers of people who make up those groups are smaller as well.

One reason for this segregation is that we tend to live in neighborhoods that are also segregated. Rich people, who are more often White, tend to live with other rich people. Because children go to schools in their own neighborhood commonly, the schools mirror the lack of integration in neighborhoods. While school segregation is against the law, segregated classrooms are alive and well.

7.5.1.4 Inclusion

In addition to prohibiting segregation based on race, ethnicity, color and gender, federal law requires that students who are labeled as “disabled” receive equitable education and educational support. This kind of discrimination became illegal with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The ADA was passed in 1990.

In order to ensure equitable education schools began to integrate classrooms. This practice, known as inclusion, moves disabled students from residential schools and separate classrooms into inclusive classrooms. Inclusion is also commonly called mainstreaming, a unique type of integration.

In one example of inclusion supported by law, the Education of All Handicapped Children Act (EHC) of 1975 included deafness as one of the categories under which children with disabilities may be eligible for special education and related services. This law required public schools to provide educational services to disabled children ages 3 to 21. This law included d/Deaf students as disabled under the law, expanding the services available to them, and increasing integration.

7.5.1.5 Educational Debt not Achievement Gap

Achievement gaps based on social location persist. As researchers and community members, we can note the facts, but the more important question is “why?” Understanding the complex causes of this persistence may help us act in ways that will close the gap. If our education is intended to be universal, all students must have both equal access and outcomes that are not based on social identity or social location.

Figure 7.18. Gloria Ladson-Billings Photo

Gloria Lasdon-Billings is an educator and an educational researcher (figure 7.18). As the president of American Educational Research Association (AERA), she gave the presidential address in 2006. She examines the achievement gap, and explores what makes the most effective teacher effective, particularly those teachers who are able to close the achievement gap for Black students. To learn more about her, you might want to read this article: Gloria Ladson-Billings: Daring to Dream in Public.

In her presidential address from 2006, Lasdon-Billings argues that sociologists should study educational debt rather than the achievement gap. Educational debt is the cumulative impact of fewer resources and other harm directed at students of color. This education debt includes economic, sociopolitical and moral characteristics. We’ll explore each of these characteristics.

According to Lasdon-Billings, the achievement gap is a relatively short term measure, similar to how a household or government may overspend its budget for a particular month or particular year. While it is troubling, it is not the actual pervasive issue. She compares educational debt to government debt (or maybe to your household’s credit card debit). In the United States, the legacy of overspending our budget created a huge debt. The interest on this debt is the third biggest expenditure of our national budget, only after the military and Social Security and Medicare. Similarly, our educational debt is a backlog of historical debt, of making education illegal for some, and then segregated for others.

The backlog consists of economic debt and unequal spending in education over decades. Because schools are funded based on population and property tax revenues, schools in rich neighborhoods (which are more likely to be White) spend more on each individual child’s education.

The third component of debt is sociopolitical, consisting of the exclusion of Black and Brown people from voting itself, and from decision making in school districts, state houses, and the federal government. Finally, she argues that education is experiencing moral debt, which brings us back to a precondition of our social problem of education. She writes, “a moral debt reflects the disparity between what we know and what we actually do.” (Lasdon-Billings 2006:8). She further asks,

What is it that we might owe to citizens who historically have been excluded from social benefits and opportunities? Randall Robinson (2000) states: No nation can enslave a race of people for hundreds of years, set them free bedraggled and penniless, pit them, without assistance in a hostile environment, against privileged victimizers, and then reasonably expect the gap between the heirs of the two groups to narrow. Lines begun parallel and left alone, can never touch (Lasdon-Billings 2006:8).

In the end, she argues that the achievement gap is an indicator of educational debt, and the wider social forces of systemic racism, poverty, and health inequities, rather than the cause of the inequality itself. The 13:51-minute video in figure 7.19 explores what educational debt looks like for one teacher and her students. As you watch, please consider how the teacher and the students experience this education debt. How might solutions change if you frame the problem in terms of education debt rather than achievement gap?

Figure 7.19. How America’s public schools keep kids in poverty [TED Video] (time 13:51).

7.5.1.6 Separate Space: Protection, Resistance, and Healing

An additional practical response to the racism, classism, heterosexism, sexism, ableism, colonialism and other -isms experienced by marginalized people is to claim separate space.

Although this looks like segregation, it is different in one essential way. These spaces are created by non-dominant groups on purpose, not imposed on them by others. They serve as a protected space, supporting non-dominant groups in forming their own healthy identities and resisting the narratives of non dominant culture.

Women established women’s only colleges, for example. In 1836, Wesleyan College in Georgia opened its doors, becoming the first women’s college in the world. Between 1836 and 1875 fifty women’s colleges and universities were created specifically to educate women. Co-ed colleges started enrolling women in the mid 1800s which also opened educational opportunities to women, particularly if they wanted to be teachers.

Separate education for d/Deaf students began in the United States in 1817. Many of the schools that were established were residential schools, where students would live away from their families. They would learn to speak and sometimes to sign. Although fewer of these schools exist today because students have been mainstreamed into public schools, the legacy lives on with Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, which specializes in serving d/Deaf and hard of hearing students. Horace Mann School for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Boston teaches both American Sign Language and English to its students.

One historical and existing separate space are the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). They were originally founded because other institutions would not accept Black students. They continue to exist to support Black students in achieving college success. Educator and activist bell hooks, who deliberately keeps her name in lower case, writes this about all-black schools:

That shift from beloved, all-black schools to white schools where black students were always seen as interlopers, as not really belonging, taught me the difference between education as the practice of freedom and education that merely strives to reinforce domination. (hooks 1994)

Today, these schools are still identified as HBCUs. However, because many of them receive federal funding, students from any race or ethnicity may attend.

Beyond reclaiming residential schools, education can be a way to address social problems when it is used to enliven language, culture and learning. We can see this healing power in efforts to restore and strengthen Native languages. In the following quote, Indigenous biologist and activist Robin Wall Kimmerer links language, culture and healing, writing that as language is restored, wholeness is restored also:

>And so it has come to pass that all over Indian Country there is movement for revitalization of language and culture growing from the dedicated work of individuals who have the courage to breathe life into ceremonies, gather speakers to reteach the language, plant old seed varieties, restore native landscapes, bring the youth back to the land. The people of the Seventh Fire walk among us. They are using the fire stick of the original teachings to restore health to the people, to help them bloom again and bear fruit. (2013:368)

Separate language and culture learning is also a source of creating equity in education. Dorothy Lazore, who teaches immersion Mohawk describes an important shift in how Native children experience schooling: “For Native people, after so much pain and tragedy connected with their experience of school, we finally now see Native children, their teachers and their families, happy and engaged in the joy of learning and growing and being themselves in the immersion setting.”(Lazore quoted in Johansen 2004:569)

Teachers and activists are using media and technology to reach their students. “The Navajo Nation’s official radio station, has been making plans to offer instruction in the Navajo language over the air in an attempt to follow Joshua Fishman’s advice that revitalized languages, to be successful, must be shared by a community of people via their own communications media. “The Voice of the Navajo Nation,” a KTNN is called, has a signal that reaches from Albuquerque to Phoenix (Johansen 2004:579)”

Here in Oregon language restoration is underway. The Confederated Tribe of the Siletz Indians (CTSI) has created a partnership with the local charter schools to restore Athabascan, one of the local Native languages. The Siletz Tribal Language Program works to strengthen the language and cultural practices of the many tribes that make up CTSI.

The genocide of people and culture that occurred when colonists established Indian Residential schools created wounds that remain unhealed today. Today, Indigenous people are reclaiming the bones of their children, their languages and ceremonies, and even sometimes the schools themselves to heal and thrive.

7.5.2 Going Deeper

Explore HBCUs in the video African American Higher Education.

More information the Siletz Tribal Langague Program: The Siletz Tribal Language Program

7.5.3 Licenses and Attributions for Social Change in Education through Law

“Social Change in Education through Law” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 7.16. Button from Washington DC Freedom March https://www.si.edu/object/pinback-button-1963-freedom-march:nmaahc_2012.159.4

Figure 7.18. Gloria Ladson-Billings Photo

https://news.wisc.edu/gloria-ladson-billings-daring-to-dream-in-public/ (appears to be fair use. The author uses this photo in public profiles PHOTO: MARCUS MILES

Figure 7.19. How America’s public schools keep kids in poverty. https://www.ted.com/talks/kandice_sumner_how_america_s_public_schools_keep_kids_in_poverty