8.2 Religion, Spirituality and None: Who Believes What?

In the chapter introduction we saw how the religious practices of Hinduism and Indigenous peoples supported environmental activism. But what do we mean when we say religion? How is that different from spirituality? And who believes what anyway? In this section, we explore the beliefs and rituals of those who practice a religious tradition and the beliefs and rituals of those who don’t.

8.2.1 Defining Religion, Spirituality and None

What is religion anyway? Sociologists define religion as a system of beliefs, values, and practices concerning what a person holds to be sacred or spiritually significant. Sociologists say that religion is an institution whose structures support belief that goes beyond the physical world. That definition is solid, but let’s dive deeper.

Religion often answers the deep life questions, questions which resist purely scientific answers: Why are we here and where did we come from? What is the meaning of life? What happens when we die? What does it mean to be a good person? Or even Why do bad things happen to good people? These questions of ethics and morals belong primarily but not only in the sphere of religion. People from many cultures wrestle with these questions, constructing different beliefs and rituals to find the answers.

8.2.1.1 Rituals

Religion often contains rituals, actions that embody the beliefs of a people and create a sense of continuity and belonging. Rituals generally involve activities performed in a particular order at a particular place at a particular time. (Amanda Zunner-Keating et al. nd). These practices assist practitioners in achieving a spiritual experience. ritual is also a way to maintain culture – a sense of shared belonging. In many ways, religion when used well, anchors community – defining a shared sense of beliefs.

Figure 8.5: Looking Back: Rituals [PBS Video] explores many rituals from world religious traditions.

Rituals include activities such as individual or communal prayer, reading holy texts, devotions to a God or Goddess, fasting, chanting, communal singing, ecstatic dance, meditation, pilgrimages and commemorating the lives or events of holy people. Watch the 5:13-minute video Looking Back: Rituals (figure 8.5) that explores many rituals from traditions across the world. As you watch please consider how these rituals are the same or different from each other. How do these practices differ from any practices you may have participated in as a child or as an adult? Also, how does ritual help to make sense of the human condition?

8.2.1.2 Spirituality

Scholars, activists and practitioners talk about spirituality as distinct from religion. According to end of life researcher Christina Puchalski, “spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.” (Puchalaski et al. 2014: n.p.) In this sense, spirituality refers to an individual experience of the divine, mystical, and transcendent.

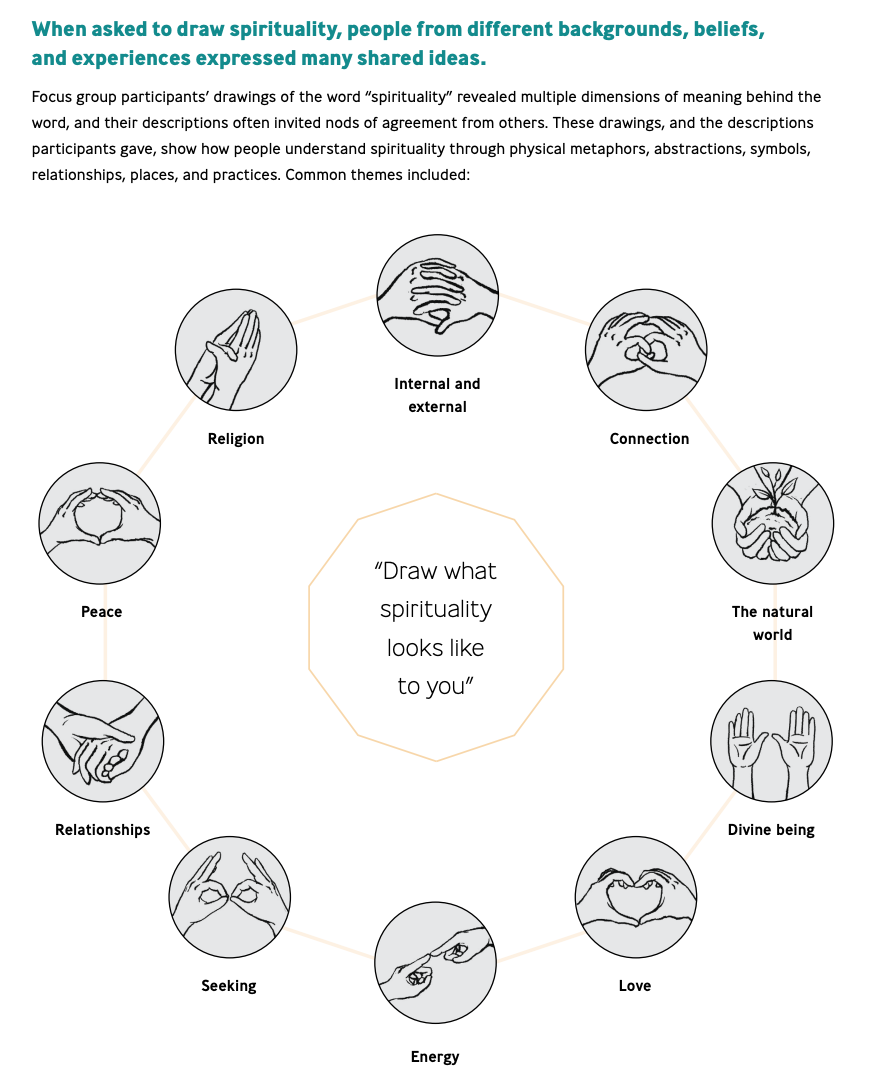

Researchers at the Fetzer Institute, an institute whose mission is “to help build the spiritual foundation for a loving world”, did a study in 2020 to learn more about this growing interest in spirituality apart from religion (Setzler et al. 2020). They asked people to draw pictures to answer the question, “What does spirituality look like to you?” If you had to draw your own vision of spirituality, what would you include?

Figure 8.6 this infographic describes what spirituality means to people in drawings.

The researchers organized the results into ten categories: External and Internal, Connection, The Natural World, Divine Being, Love, Energy, Seeking, Relationship, Peace, and Religion (figure 8.6). Each of these categories describes how a person might have an experience of the sacred.

8.2.1.3 Spiritual but not religious

You may have heard the term “spiritual but not religious.” People who identify this way often focus on the individual experience of connection or belonging rather than membership in a particular religious organization. They may say that they find meaning in watching a beautiful sunset. They may find purpose in serving others, without needing to connect with a church. Some of them may have come to their spirituality through twelve step addiction recovery groups, but they don’t attend religious services. They may hold strong ethical principles but not reference God or commandments in order to do this.

People who define themselves as spiritual but not religious often choose that term because they see institutions of religion as causing harm, corrupt, or meaningless. However, defining religion and spirituality as in opposition to each other is also limiting. Many people consider themselves spiritual and religious, for example. The structures and rituals of their faith community support them in finding an individual experience of connection (Mercadante 2020).

8.2.1.4 Interspirituality

An additional category of people who don’t fit neatly into the traditional boundaries of religion and spirituality are the people who practice interfaith or interspiritual religions. As you will remember from Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, we live in a considerable globalized world. Economically, we recognize that we are interconnected.

Similarly, there is a growing community that recognizes that many world traditions have beliefs and practices that contain wisdom. Mystic Wayne Teasdale describes interspirituality, the idea that beneath the diversity of theological beliefs, rites, and observances lies a deeper unity of experience that is our shared spiritual heritage. One Spirit, an interspiritual seminary, describes interspirituality in this way:

At One Spirit, we respect and honor the differences of the many paths as we celebrate and value our sameness – we know all spiritual traditions share universal teachings, which bring us together as ONE in harmony.

Whether you look to Yahw-h or Jesus, Mohammed or the Dalai Lama …whether you find freedom in the heavens or grounding in the earth…whether you practice in silence or in jubilant sound…we believe that at the core, we are all one (One Spirit Learning Alliance 2021:n.p.).

Religious traditions that take interspirituality at their core include Unity and Religious Science from the New Thought traditions, Baha’i and Unitarian Universalists. In addition, mystics from many traditions also assert this fundamental oneness as part of their practice. According to Mirabai Starr, a mystic is a person who has a direct experience of the divine, unmediated by conventional religious rituals….” (Starr 2019: 225). In this direct experience, mystics often see the oneness of all life.

8.2.1.5 Religious Nones

Finally, some people define themselves as religious “nones”—those who answer “none of the above’ ‘ on religious identification surveys. These people may have left a faith tradition of their birth which no longer serves them. They may have grown up in a household that practiced no religious or spiritual tradition. They may be atheist, not believing in God or a higher power, or agnostic, believing that there is no proof of God or a higher power.

Some people who identify as non religious – whether spiritual but not religious or none – have deep commitments to ethical principles and social justice. They make these commitments outside of a framework of organized religion. For example, researcher Lori Beaman studied people who are involved in sea turtle rescue. She explores how people who identify as spiritual engage in social change. She writes, “sea turtle conservation illuminates cooperation between religious and nonreligious actors through the project of rescuing stranded or vulnerable sea turtles—and in uncovering how different worldviews can nonetheless result in a shared commitment to action. (Beaman 2017:18).” She found that rescuers see themselves as belonging to a community engaging in world repair. This community gives them a deeper purpose, and a sense of belonging to something greater than themselves.

One volunteer, who identifies as spiritual but not religious, expresses her connection to sea turtles in this way:

The spirituality that I have is in regard to probably any living thing. I feel a bond, I have a connection,and –even a spider …Even the smallest thing .…when it gets more spiritual is when I think we give of ourselves to something else. It could be a person, it could be an animal, it could be an insect …, when you go to save an insect, or an animal, or a person you get something back from that, and it’s just a sense of peace and fulfillment that I feel within my heart, within my soul. (Beaman 2017:20)

This volunteer is not religious. However she finds meaning and belonging in connecting with the human and non-human animals, engaging in the repair of the world.

Sociologists often focus on examining the institution of religion. As we consider social change, however, even this focus is shifting. We now explore questions of spirituality and belief within and without formal structures. As you consider these concepts of religion, spirituality, belief and ritual for yourself, where do you fit?

8.2.2 Diversity of World Religions

Figure 8.7 Symbols of World Religions. How many can you identify?

Beyond the basic purposes of religion, though, who believes what? In figure 8.7, you see some of the symbols that identify many of the world religions. How many world religions are there, really? The answer to that question is strangely complicated. It depends a bit on how big of a group you count as a religion. For example, you could count everyone who identifies as Christian to be part of one religion. Or, you could draw finer distinctions and say that Catholics, Baptists, Pentecostals, Quakers, and Evangelical Christians each belong to different religions. The finer the distinction, the more religions we count.

Although opinions differ on how many religions there are, most lists include: Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. To understand the basic beliefs of each tradition, please watch this 11-minute TED talk: “The five major world religions” in figure 8.8. As you watch you may want to consider how these traditions are the same or different from each other.

Figure 8.8 The five major world religions – John Bellaimey [YouTube Video]

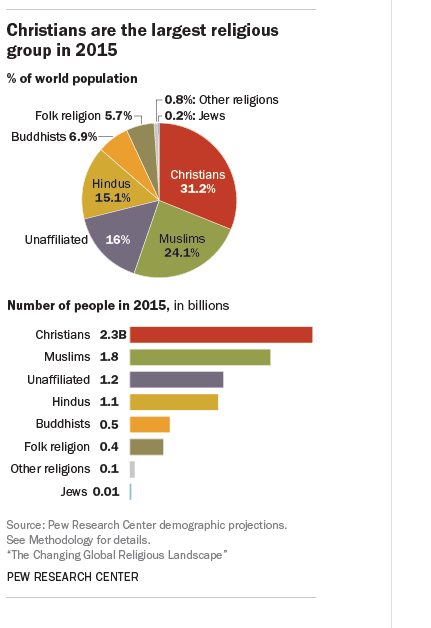

These world religions include approximately 77 percent of all the people on the planet, as seen in the chart in figure 8.9, developed by Pew Research (Pew 2015). In their study, they also include folk religions, other religions, and unaffiliated people, so that they can count everyone. When you look at this chart, where do you find yourself somewhere in the percentages?

Figure 8.9 The Changing Global Religious Landscape.

You might notice that this chart also includes unaffiliated people, folk regions and other religions. We’ve already talked about people who might define themselves and unaffiliated – people who are spiritual, agnostic, atheist or none. In the category of folk religions, Pew Research includes “African traditional religions, Chinese folk religions, Native American religions and Australian aboriginal religions” (Pew 2015). However, it is important to point out that many people who practice these traditions wouldn’t consider them religions (King 2013). The chart also includes a category for other religions, which Pew Research defines as “an umbrella category that includes Baha’is, Jains, Sikhs, Taoists and many smaller faiths” (Pew 2015).

As useful as this chart is, though, it may not help us explain all of the diversity that we find in religious groups and practices. For example, we know that Catholics and Protestants disagreed about the practice of baptism in the 16th century. On this chart, they are both considered Christian. An infographic that shows some of the more granular categorization is A Demographic breakdown of the world of religion. Although the exact numbers may change over time, we can see how the larger categories of religion become more specialized as we get more specific about beliefs and practices. In order to better understand religion, sociologists use the following categories:

A sect is a small and relatively new group. Most of the well-known Christian denominations in the United States today began as sects. For example, the Methodists and Baptists protested against their parent Anglican Church in England, just as Henry VIII protested against the Catholic Church by forming the Anglican Church. From “protest” comes the term Protestant.

Occasionally, a sect is a breakaway group that may be in tension with larger society. They sometimes claim to be returning to “the fundamentals” or to contest the veracity of a particular doctrine. When membership in a sect increases over time, it may grow into a denomination. Often a sect begins as an offshoot of a denomination, when a group of members believes they should separate from the larger group.

Some sects do not grow into denominations. Sociologists call these established sects. Established sects, such as the Amish or Jehovah’s Witnesses fall halfway between sect and denomination on the ecclesia–cult continuum because they have a mixture of sect-like and denomination-like characteristics.

A denomination is a large, mainstream religious organization, but it does not claim to be official or state sponsored. It is one religion among many. For example, Baptist, African Methodist Episcopal, Catholic, and Seventh-day Adventist are all Christian denominations. Sunni, Shia and Sufi are all Muslim denominations. Mahayana, Vajrayana and Theravada are Buddhist denominations.

An ecclesia, originally referring to a political assembly of citizens in ancient Athens, Greece, now refers to a congregation. In sociology, the term is used to refer to a religious group that most all members of a society belong to. It is considered a nationally recognized, or official, religion that holds a religious monopoly and is closely allied with state and secular powers. The United States does not have an ecclesia by this standard; in fact, this is the type of religious organization that many of the first colonists came to America to escape. There are countries that have an official state religion, and these do then have an ecclesia. You might find the chart (it’s on page 7 of the link) in this article interesting: Which Countries Have State Religions?

In the end, it may be less important to ascertain the precise number of religious or spiritual groupings that humans can create. A more interesting sociological question might be: Why do religious and spiritual practices serve us? Let’s turn our attention to some sociological explanations.

8.2.2.1 Going Deeper

- Religious and spiritual rituals are often unique expressions of cultural identity. To learn more you may want to explore these practices: The Power of Ritual, An Honor Song for people who are surviving Domestic Violence, and Ancestral Masquerade of Egungun

- The Fetzer Institute study, What Does Spirituality Mean to Us is a powerful explanation of spirituality in the United States. As you look at this research, you will see art from many people. Using images or drawings to gather responses is powerful but unusual. Where else might researchers use this method?

8.2.3 Licenses and Attributions for Religion, Spirituality, and None

“Religion, Spirituality and None” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0. With the exception of the definitions of sect, denomination and ecclesia which are from:

“Introduction to Sociology 2e”. Authored by: OpenStax CNX. Located at: http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d/Introduction_to_Sociology_2e. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@3.49

8.5 Video: Looking Back: Rituals

8.6 Infographic What Does Spirituality Mean to Us? Used with permission

8.7 Symbols of World Religions. How many can you identify? (This image will be replaced by an open source version in the next edition of this book.)

8.8 Title of Video: The Five major world religions