8.4 Emerging Changes in Religion

So far, we have explored some of the common ways that sociologists and religious scholars talk about religion, and we have learned about many of the world faith traditions. Sociologists also look at how religion both supports existing inequalities and can be used to dismantle them. In Chapter 2 we reviewed social location: the many intersections of our experience related to race, religion, age, physical size, sexual orientation, and social class. In this section, we’ll use social location as our lens for illustrating how power, privilege and belief intersect to maintain or dismantle unequal social structures.

8.4.1 The Power of Religion in Slavery, Reconstruction and Civil Rights

Many people in the United States know that Martin Luther King Jr. was a civil rights leader. Some of them also know that he was a minister and had a PhD in divinity – the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr.. Further, sociologists often credit the organizational power of “The Black Church” as part of the reason that the Civil Rights Movement was successful. This 3:37-minute video, The Role of the African American Church in the Civil Rights Movement, summarizes this history (figure 8.24). As you watch, please consider how religious institutions, either Black-organized or White-organized, may have played a role in the social change of the Civil Rights Movement.

Figure 8.24 The Role of the African American Church in the Civil Rights Movement [YouTube Video]

8.4.1.1 Christianity and the Slavery era

When we consider the institution of slavery in the United States, we know that the harm was complex and multigenerational. When we focus more specifically on how religion played a role in this damage, we see two issues. First, Christianity itself was proslavery. For White people, theology asserted that men and women of African descent were not truth-tellers. They could not morally and ethically discern right from wrong. Enslaved men and women were not considered trustworthy, even after they converted to Christianity, because they were deemed inherently sinful and morally inferior. (Pierce 2015: n.p.) In practical terms, some Christian churches even sponsored some of the slaves ships and journeys to capture and transport enslaved Africans. (Pierce, as quoted by Weil, 2019). These beliefs are part of the colonialist myths that we learned about in Chapter 4.

When we look at this theology from the point of view of the people who were slaves we find that discussions of salvation in the Black church have been intertwined with how to contend with White supremacy. We can define White supremacy as the belief, theory, or doctrine that white people are inherently superior to people from all other racial and ethnic groups, and are therefore rightfully the dominant group in any society.

Among many slaves the discussion of salvation emphasized obedience and hard work. Slave holders wanted docile slaves, and slave preachers hoped to protect Blacks from the harsh repercussions of challenging White supremacy. Similar religious rhetoric continued after slavery as preachers influenced by Booker T. Washington and William Hooper Council, emphasized the need for chastity, thrift, and hard work over political action.

Figure 8.25 Image of the Family Record. The record contrasts the family before the Civil War, and after the Civil War.

When slavery was abolished in 1865, religion and the Black church began to become a source of healing for Black families. Because one of the components of slavery was that structures of families were destroyed, healing meant creating legal, recognized families. Many freed people rushed to solemnize unions with formal wedding ceremonies. Figure 8.25 shows a family record from this time. Black people’s desires to marry fit the government’s goal to make free Black men responsible for their own households and to prevent Black women and children from becoming dependent on the government.

Many churches served as schoolhouses and as a result became central to the freedom struggle. Free and freed Black southerners carried well-formed political and organizational skills into freedom. They developed anti-racist politics and organizational skills through anti-slavery organizations turned church associations. Liberated from White-controlled churches, Black Americans remade their religious worlds according to their own social and spiritual desires.

One of the more marked transformations that took place after emancipation was the proliferation of independent Black churches and church associations. In the 1930s, nearly 40% of 663 Black churches surveyed had their organizational roots in the post-emancipation era. Many independent Black churches emerged in the rural areas and most of them had never been affiliated with White churches.

Many of these independent churches were quickly organized into regional, state, and even national associations, often by brigades of northern and midwestern free Blacks who went to the South to help the freedmen. Through associations like the Virginia Baptist State Convention and the Consolidated American Baptist Missionary Convention, Baptists became the fastest growing post-emancipation denomination, building on their anti-slavery associational roots and carrying on the struggle for black political participation.

Black churches provided centralized leadership and organization in post-emancipation communities. Many political leaders and officeholders were ministers. Churches were often the largest building in town and served as community centers. Access to pulpits and growing congregations, provided a foundation for ministers’ political leadership. Groups like the Union League, militias and fraternal organizations all used the regalia, ritual and even hymns of churches to inform and shape their practice.

8.4.1.2 The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement added action to the message of liberation preached by the Black Church. While only a minority of Black churches participated, Morris illustrates the indispensable role those black churches played in providing resources for the growing desegregation movement (Morris 1984). Black churches provided the leadership and membership base for organizations such as the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), financial support, meeting spaces, and communication networks (Morris 1984, Calhoun-Brown 2000).

The most prominent leader of the Civil Rights Movement, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., represented the dialogic relationship between faith and action. He used the social gospel, which shaped many black churches, to interpret democracy in the United States. He also used democracy in the United States to interpret the legitimacy of the movement. This social gospel perspective, which viewed racial and economic oppression as social evils that Christians had a moral duty to resist, led King to view the church as equally instrumental to both individual and social salvation.

The combination of the social gospel and traditions of the Black Church even influenced the development of other organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The religious beliefs of activists sustained the movement in the face of violence and emboldened individuals to stand up to a White supremacist system.

In this story, we see organized religion supporting White supremacy and providing the structures and stories needed to challenge that same system. This pattern is not unique. Let’s keep looking.

8.4.2 Colonialism, Syncretism, and Día de los Muertos

Another story of the power of religion as an influencer of social change is told as we look at the origins of Día de los Muertos/Day of the Dead. This story illustrates how Indigenous Aztec people wove their spiritual practices with the colonizing Spanish Catholics throughout the Americas to resist colonization in plain sight.

Figure 8.26 Photo of Wall with Stucco Covered Skulls at the Templo Mayor, Aztec Origin, Mexico City.

8.4.2.1 Colonialism

The Aztecs were Indigenous people who lived in the land that now makes up central Mexico. They founded the city of Tenochtitlán in 1325, on land that is currently Mexico City. Tenochtitlán became a center of population, art and culture. The image in figures 8.26 shows a wall covered in stucco skulls, part of the architecture of this city. The empire lasted from about 1300 to 1521.

Figure 8.27 Image of Mictlantecuhtli

Figure 8.28 Photo of a person representing Mictlantecuhtli

The Aztecs worshiped many gods and goddesses. Among these were Mictlantecuhtli (figures 8.27 and 8.28) and Mictecacihuatl the god and goddess of the underworld. In Aztec stories, they meet the souls of the dead, preside over the afterlife, and gather the bones of the dead to give to the other gods

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in Mexico in 1519, they were awed by the complexity of the city. “It was all so wonderful that I do not know how to describe this first glimpse of things never heard of, seen or dreamed of before,” wrote conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo. (Fredrick 2019: n.p.). The Spanish allied themselves with rival indigenous empires in order to appropriate land for the Spanish crown, convert inhabitants to Catholiscsm and plunder for gold and other resources. The war lasted about three months. Between the violence and the related smallpox contagion, the city fell , the Aztec empire lost power. The result was a genocide of the Aztec people.

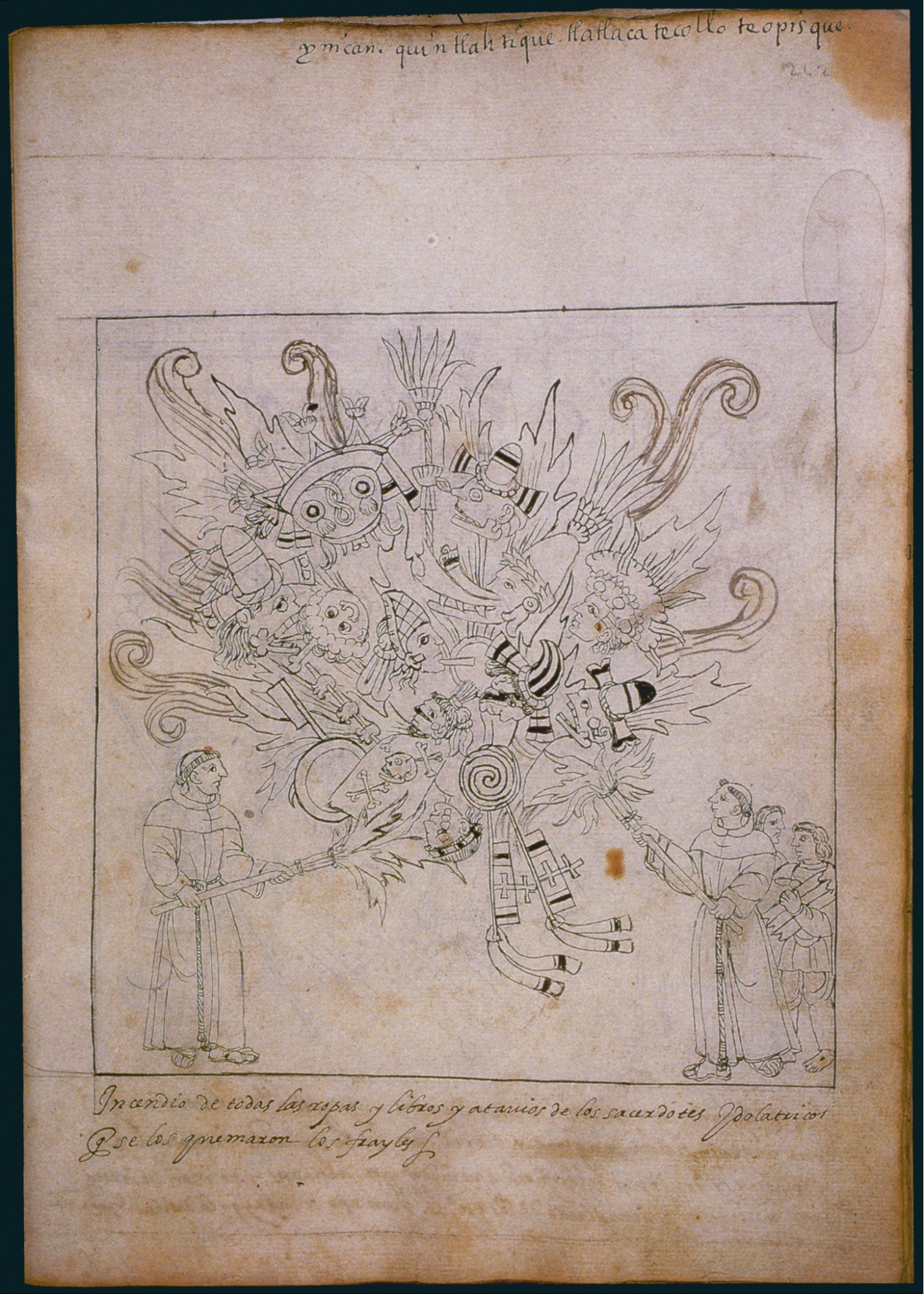

Figure 8.29 Photo of in image of the destruction of religious statues and objects in Tlaxcala

It was during this time that we began to see the beginning of the spread of Catholicism in the Americas. The Spanish conquerors burned religious statues and objects, as shown in figure 8.29. One account describes this practice and this picture:

In pre-Hispanic times, Aztec priests and select deity “impersonators” would transform themselves into particular deities by preparing themselves ritually and then donning the appropriate masks and paraphernalia. Catholic priests tried to close down this conduit to an indigenous otherworld by banning ceremonies, destroying paraphernalia and punishing participants. Bonfires such as the one shown here were held across Spanish America in the 16th century and painted books, ancestor bundles and other relics sacred to indigenous peoples were publicly destroyed. (Leibsohn and Mundy 2015: n.p. )

Spanish Catholic colonizers forbid Indigenous rituals and practices, and destroyed sacred objects, as one way of gaining power.

The initial destruction of people and culture was only a first step. As we move north, and examine the history of California, we notice that Spanish friars, part of the monastic orders of Spain, established 21 missions in the territory that comprises California, from 1769 to 1823. The goal of the mission was to convert the Indigenous peoples to Christianity and to control the economic wealth of the surrounding land. Like residential schools in Canada and the United States, discussed in Chapter 7, these missionaries forced the Indigenous people to become captive laborers, convert to Catholicism and work in agriculture. Although the Fransiscans established these missions to do the forced religious conversions, and “civilize” the indigenous people, the missions were also ways for Spain to control the land.

The conversion work of the missionaries has far reaching consequences. Until the 1960’s almost 90% of Latin Americans identified as Catholic. More recently, as of 2014, less than 70% of the people in the region identify as Catholic, but many others identify as Christian (Pew 2014: n.p. ).

8.4.2.2 Religious syncretism and Día de los Muertos

However, the way that the religion is practiced is unique, blending Catholic beliefs with beliefs and practices from indigenous and African roots. This concept is known as religious syncretism, the fusion of diverse religious beliefs and practices. It is common in Mexico and Bolivia, for example, to make offerings of food, drinks, candles or flowers to spirits of the ancestors. (Pew 2014). These combinations of diverse beliefs and rituals are evident in Día de los Muertos/Day of the Dead.

The 2:44-minute video in figure 8.30 shows some of the common practices for the Day of the Dead celebration. As you watch, see if you can notice symbols from different faith traditions. How do the altars and celebrations become a source of strength for the people who celebrate. Finally, how is this practice the same or different from Halloween?

Figure 8.30 Dia De Los Muertos in Los Angeles [YouTube Video]

The Day of the Dead/Día de los Muertos blends Catholic and Indigenous spiritual practices to remember and celebrate loved ones who have died. Families create ofrendas, or altars, with pictures of loved ones who have died. They add the food and drink that the person loved in life, and other objects that capture their unique personalities. Ofrendas are often decorated with flowers, often marigolds, candles, religious statues and rosaries. Because this celebration celebrates Indigenous practices as well as Catholic ones, The Day of the Dead/Día de los Muertos is also a celebration of resistance. The colonizers didn’t completely win. Researchers Steward and Lozano describe it this way:

Another example of the intersection of religion, spirituality, and culture is the Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebration, which is celebrated annually by some Latinos, particularly those of Mexican origin. Día de los Muertos blends pre-Columbian indigenous rituals with Catholic beliefs and practices into a uniquely Mexican celebration that honors deceased loved ones while recognizing death as a part of life. The concept of resistance is an important cultural/political aspect of Día de los Muertos.” (Stewart and Lozano 2009:27)

The two researchers work at college student services. They emphasize that celebrating Día de los Muertos supports Hispanic/Lantinx students in not only celebrating their culture, but finding strength and power in this connection.

Some women in Mexico are doing just that. They are using religious power and imagery to protest the killings of women that are common in Latin America. According to the United Nations, “Latin America is home to 14 of the 25 countries with the highest rates of femicide in the world. Ninety-eight per cent of gender‑related killings go unprosecuted.“ (Mohammed 2018: n.p.) Calling their protests the Day of the Dead Women/Día de las Muertas (changing Muertos to Muertas signifies that you are talking about women), protesters marched and rallied. They often carried pictures of their mothers, sisters and daughters who had been killed. Some of them dressed as La Catrina, a woman dressed in a fancy hat with flowers and feathers, with her face painted like a skull. La Catrina symbolizes death, but more than that, she reminds us that death comes for all of us.

Figure 8.31 Photo: A woman protests femicide in Mexico, covering half her face with the skull makeup of La Catrina and half uncovered.

The woman in the photo in figure 8.31 uses the power of the religious symbolism of La Catrina, and the religious and cultural importance of Día de los Muertos to draw attention to the horror of the killings of women that are happening in Mexico. By connecting with these practices, she is able to protest in powerful ways.

In Día de los Muertos, we see the historical oppression of colonization, the Indigenous resistance in syncretism, and the emerging power of protesters to create social change. However, the relationship between religion, gender, violence and social change is complicated. Let’s look at the protests of women in Iran to learn more.

8.4.3 Religion, Gender and Violence

When we explored a feminist approach to the sociology of religion, we examined language, belief, leadership and activism. However, when we look through the lens of social change, we can also examine how gender based violence is both supported and challenged by religious beliefs and religious organizations.

Gender based violence is violence directed against a person because of his or her gender and expectations of his or her role in a society or culture. This wider definition includes women, non-binary or transgender people and occasionally men, if they experience gender related violence. Religion is not the only institution that supports the abuse of women, non-binary people, and children. However, many religious communities are more likely to cover up gender-based violence due to their view of the sanctity of the family. Because they consider the family a divinely ordained institution, its preservation takes precedence over the revelation of cases of domestic violence (Nason-Clark 2000; Nason-Clark 2018).

8.4.3.1 An examination of gender based violence and religion

The feminist perspective in sociology argues that the root of gender-based violence is patriarchy, which is still prevalent in all social institutions including religion. However, in the context of religious traditions and beliefs, patriarchy is sometimes embedded in the structure and theology. There are also harmful gender norms such as early or forced marriage and genital mutilation that contribute to violence against women in some religious communities. Lack of legal protection is another factor that prevents women seeking and getting justice. Poverty and economic deprivation that many women experience across the world could make it extremely difficult for women to extricate themselves from abusive relationships. Finally, under-representation of women in power and politics means that women have fewer opportunities to shape policies that combat gender-based violence.

Gender-based violence is a relatively new area of research across social sciences. However, since the1980s, there have been ample studies in Christian churches across the western world that shed light on the extent and severity of gender-based violence in religious communities. The other challenge when it comes to researching gender-based violence is the independence of religious institutions in western democracies. In western democracies, because of the separation of religion and state, religious institutions are exempt from some financial and legal responsibilities. Therefore, they are not required to report cases of abuse to state authorities.

For instance, in Australia, religious institutions are considered charitable organizations (McPhillips 2015) and not legally responsible like other mainstream institutions and thus victims have fewer legal resources. Recent scandals in both in the Catholic church and various Protestant denominations in America have revealed some disturbing facts on the extent and cover-up of sexual violence (Hidalgo and Doyle 2007, Plante 2020).

Gender-based violence is also a subject of inquiry in Islamic societies. In some cases, due to religious, cultural and legal constraints, victims cannot or are not willing to come forward to register their cases (Naciri Hayat 2018). Honor killing and child bride practices are examples of gender-based violence in Islamic societies. Gender-based violence in Islamic societies as in other cultures takes place at three levels: physical, legal and social. Women in countries where the Islamic Sharia laws (Iran, Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia) are enforced are considered wards or property of men. Sometimes, men kill or beat women in their families who are disobedient or viewed as dishonoring their families.

Responses to gender-based violence in religions institutions

As part of an effort to address issues around gender based violence in religious communities several scholars at Columbia University initiated an academic project: “Religion and the Global Framing of Gender Violence”. They examine the role of religion in naming, framing, and governing gendered violence. Pressure from both the victims and laypeople within faith-based organizations has prompted several Christian churches and Jewish groups to act and address this problem head on. A wide variety of programs and projects have been proposed by these organizations. They range from inclusion of women in the hierarchy of these organizations, reaching out to the victim, developing educational programs, offering support legally, and creating safe houses for the victims.

There is also a global movement to end gender-based violence in religion. Thursday in Black is an effort by The World Council of Churches to address and tackle this issue. In Islamic countries, gender-based violence is also very prevalent. The response from women has been powerful. Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Iranian women have been subjected to discriminatory and abusive treatment by Iran’s theocratic state, a government ruled by or subject to a deity or its representative officials who are viewed as divinely guided. These women have not remained silent.

On Mahsa Amini is a young Kurdish-Iranian woman who was murdered by the morality police in Iran, because she allegedly violated the Iranian law that requires women to wear a hijab. (The police say that she experienced health problems while in custody.) Her death sparked protests in Iran, which began after her funeral on September 17, 2022. Protesters attacked symbols of the regime. Some women protesters removed their hijab as a way of resisting. Students, teachers, farmers, and professionals marched in the streets in Iran. The photo in figure 8.32 is a protest sign written in Kurdish. Translated, it says, “Jina, dear! You will not die. Your name will turn into a symbol.”, and it includes #MahasaAmini as a hashtag.

Figure 8.32 is a Photo of a protest sign: It displays the epitaph on Mahsa (Jina) Amini’s grave, in Kurdish, that reads “Jina, dear! You will not die. Your name will turn into a symbol.”

This movement is gaining support around the world. People are marching in protests in Seoul, Beirut, Santiago, New York, Rome, London, and other places around the world. Some women are cutting their hair in solidarity. Many religious and spiritual traditions include cutting hair as a symbolic gesture or ritual. Indigenous and African people often cut their hair as part of mourning rituals. Buddist monks shave their heads when they take vows.

In this case, protesters are giving an ancient ritual a modern twist by cutting their hair to show solidarity. In the 9:23-minute video “Women around the World cut their hair in solidarity with Iranian protesters,” (figure 8.33) we see religious power and beliefs on both sides of the conflict. As you watch, please consider how the government is using religious beliefs and institutions to prevent social change. How are the protesters using religious beliefs and practices to initiate social change? How are women’s rights linked to freedom for all people in the country?

Figure 8.33 Women around the world cut their hair in solidarity with Iranian protesters | DW News [YouTube Video]

Tise story of gender violence, women’s rights and religion is played out on the world stage. The players use religious beliefs and practices to uphold their existing power, or to resist it.

8.4.3.2 Going Deeper

Video of Martin Luther King, describing the Social Gospel Martin Luther King, Jr. – Influence of Social Gospel Mov’t

8.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for Religion and Social Location

“Religion and Social Location” by Kimberly Puttman and Arfa Aflatooni is licensed under CC BY 4.0. with the following exceptions:

Theology of black churches (https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2019/04/05/understanding-the-future-of-black-politics-means-understanding-the-future-of-the-black-church/

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported.)

Black churches after reconstruction African American History and Culture by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License,

Edited for brevity

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2019/04/05/understanding-the-future-of-black-politics-means-understanding-the-future-of-the-black-church/ This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license CC-BY-4.0

Figure 8.25 Title of Video The Role of the African American Church in the Civil Rights Movement

Figure 8.26 Image of the Family Record. The record contrasts the family before the Civil War, and after the Civil War.

Figure 8.27 Photo of Wall with Stucco Covered Skulls at the Templo Mayor, Aztec Origin, Mexico City. Public Domain

Figure 8.28 Image of Mictecacihuatl

Figure 8.29 Photo of a person representing Mictlantecuhtli

Figure 8.30 Photo of in image of the destruction of religious statues and objects in Tlaxcala. Public Domain

Figure 8.31 Title of Video: Día De Los Muertos/Day of the Dead in Los Angeles.

Figure 8.32 Photo: An old woman protests femicide in Mexico, covering half her face with the skull makeup of La Catrina and half uncovered. Fair Use

“Religion, Gender and Violence” by Arfa Aflatooni is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.33 Photo of a protest sign: It displays the epitaph on Mahsa (Jina) Amini’s grave, in Kurdish, that reads “Jina, dear! You will not die. Your name will turn into a symbol.”

Figure 8.34 Title of Video: Women around the world cut their hair in solidarity with Iranian protesters