9.5 Social Movements and the Environmental Crisis

It is often the deep and varied inequalities we have discussed in this chapter that prompt social movements. Similarly, many of the environmental concerns we have discussed in this chapter have prompted social movements. These two sets of social movements have tended to exist independent of each other.

However, more recently, as a result of our heightened environmental crisis, social movements that combine concerns of social inequality and the environment are arising. This merging of movements represents a significant shift in perspective. Tania Roa expresses the values behind that shift this way:

When we separate humans from nature, we perpetuate the idea that we are different from or superior to other species, when in reality we are just as much a part of natural cycles and the Earth’s ecosystems as every other creature. It’s time we shift our mindset from compartmentalizing different causes to a more holistic perspective. Then, we can combine efforts to protect all people by addressing environmental injustices, and all living things.

(How to Protect People and Planet 2023)

Let’s look at some ways that emerging social movements are shifting perspectives, encouraging better care for the planet, while improving lived experiences for members of societies.

9.5.1 Changes in Perspective

Social movements, as they involve large numbers of people working together to deal with a social problem, always hold an underlying request for a change in perspective. A key change in perspective common to several social movements responding to the environmental crisis includes shifting from colonized, or Western views of the environment to a more indigenized perspective. Let’s take a look at that Western view to frame the comparison, then explore some of the shifts.

9.5.1.1 Frontier Ethic

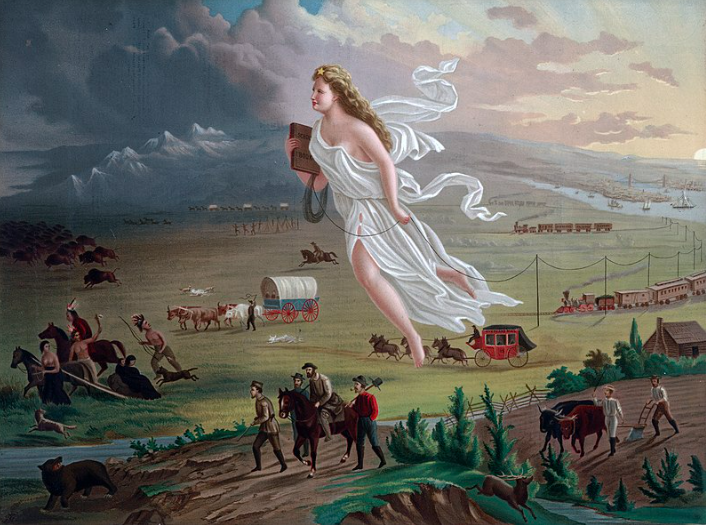

The ways in which humans interact with the land and its natural resources are determined by ethical attitudes and behaviors. Early European settlers in North America rapidly consumed the natural resources of the land. After they depleted one area, they moved westward to new frontiers. Their attitude towards the land was that of a frontier ethic.

A frontier ethic assumes that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources. If resources run out in one area, more can be found elsewhere or alternatively human ingenuity will find substitutes. This attitude sees humans as masters who manage the planet. The frontier ethic is completely anthropocentric (human-centered), for only the needs of humans are considered.

Figure 9.41. The 1872 painting by John Gast, “American Progress” was widely distributed as an engraving called “Spirit of the Frontier”. It represents Manifest Destiny, the belief in westward expansion of the United States from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Settlers are moving west, guided and protected by Columbia, the Spirit of the Frontier. They are aided by modern technology like railroads, and driving Native Americans and bison into obscurity.

Most industrialized societies experience population and economic growth that are based upon this frontier ethic, assuming that infinite resources exist to support continued growth indefinitely. In fact, as we discussed in Chapter 3, economic growth is considered a measure of how well a society is doing. The late economist Julian Simon (1932-1998) suggested that (in his lifetime) life on earth had never been better, and that population growth means more creative minds to solve future problems and give us an even better standard of living. However, now that the human population has passed seven billion and few frontiers are left, many are beginning to question the frontier ethic.

9.5.1.2 Land Ethic

Aldo Leopold, an American wildlife natural historian and philosopher (figure 9.42), advocated for a perspective in contrast to the frontier ethic. In his book, A Sand County Almanac, he introduced biocentrism: a philosophy that extends equal and inherent value to all living beings. He suggested that humans had always considered land as property, just as ancient Greeks considered slaves as property. He believed that mistreatment of land (or of slaves) makes little economic or moral sense, much as today the concept of slavery is considered immoral. All humans are merely one component of an ethical framework.

Figure 9.42. Aldo Leopold with quiver and bow seated on rimrock above the Rio Gavilan in northern Mexico while on a bow hunting trip in 1938.

Leopold suggested that land be included in an ethical framework, calling this the land ethic:

“The land ethic simply enlarges the boundary of the community to include soils, waters, plants and animals; or collectively, the land. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow members, and also respect for the community as such.” (Aldo Leopold, 1949)

Leopold maintained that the conservation movement must be based upon more than just economic necessity. Species with no discernible economic value to humans may be an integral part of a functioning ecosystem. The land ethic respects all parts of the natural world regardless of their utility, and decisions based upon that ethic result in more stable biological communities.

“Anything is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends to do otherwise.” (Aldo Leopold, 1949)

9.5.1.3 Sustainability

Many questioning the frontier ethic value a sustainable ethic. Sustainability refers to the sociopolitical, scientific, and cultural challenges of living within the means of the earth without significantly impairing its function. Sustainability proponents see the earth as having limited resources and strive to put limits on human activities (e.g., uncontrolled resource use) that may adversely affect the natural world.

Values related to sustainability can be traced to the oral histories of indigenous cultures. For example, consider the perspective of members of the Haudenosaunee nations (the Haudenosaunee confederation consists of the five nations: Mohawk, Cayuga, Seneca, Onondaga and Oneida.). They follow a ‘Law of the Seventh Generation’ which takes into consideration those who are not yet born but who will inherit the world. The Haudenosaunee confederation website explains:

In their decision making Chiefs consider how present day decisions will impact their descendants. Nations are taught to respect the world in which they live as they are borrowing it from future generations. (Anon 2023)

Watch the 2-minute video, “The Relationship between Humans and Nature | Native America: Nature to Nations” (figure 9.43) for a good synopsis of how members of the Haudenosaunee confederation view our relationship with the earth.

Figure 9.43. “The Relationship between Humans and Nature | Native America: Nature to Nations [Video]”.

Woven into perspectives of indigenous communities is that all parts of the ecosystem are connected, and that humans, animals, plants, and rocks are dependent on one another for survival and ecological health. Indigenous communities represent a long tradition of living sustainably with the natural world by preserving natural resources, using them in moderation, and respecting the interdependence of all living things.

A sustainable ethic assumes humans must use and conserve resources in a manner that allows their continued use in the future. This value system also assumes that humans are a part of the natural environment. That is, we are affected by natural laws and exist as part of the natural world. We suffer when the health of a natural ecosystem is impaired. Therefore, it is best that we live as part of the earth, share the earth’s resources with other living things, maintain the integrity of natural processes, and cooperate with nature rather than attempting to be managers of it.

9.5.2 Social-environmental movement sectors

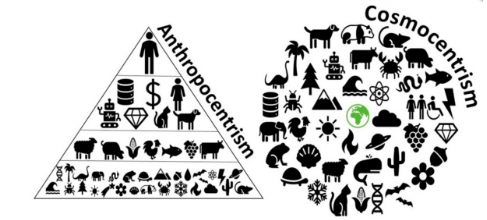

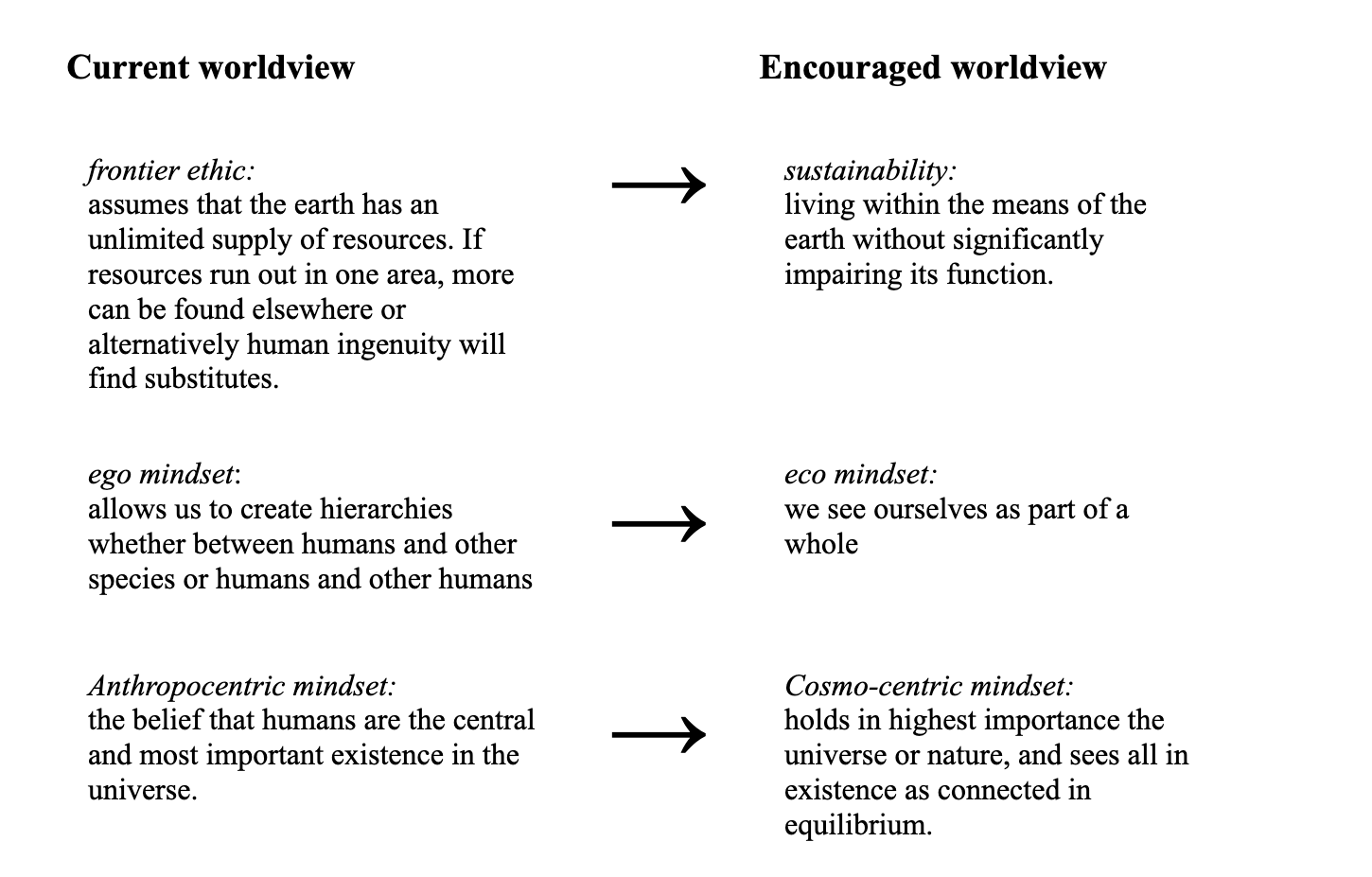

You may be starting to notice a couple themes within these calls to shift perspectives. First, in the shaping of social movements it can be powerful to put terms to worldviews that are seen as no longer useful. For example, creating the term, ego mindset, as Tania Roa introduced, helps environmentalists illustrate an eco mindset. Devising the term: frontier ethic helps us identify the value of a sustainability worldview. Similarly, as was introduced in Chapter 8, naming that humans can have an anthropocentric view of life helps us point toward a cosmo-centric worldview instead.

The second theme you may be noticing is that there are similarities among these calls for shifts in perspective. See figure 9.44 for an overview of those worldviews. How would you describe the similarities that you see?

Figure 9.44 outlines some views deemed problematic, and the corresponding views that are encouraged by sectors of the social-environmental movement. Image Description.

In figure 9.17 above we described how multiple social movement organizations concerned about the same issue form a social movement industry. The multiple terms in figure 9.44 represent the ways that members of different social-environmental movement sectors define a problem we face, and how they define a solution.

9.5.3 The Sustainable Ethic in Action

A number of movements evolved from these shifts in perspective. One is centered around the notion of sustainability. It’s estimated that since around (1000 BC to AD 1000) indigenous communities in North America have applied what we now call sustainable agriculture (Minderhout 2009). Developed as a Western term in the 80’s, sustainable agriculture became known as an integrated system of plant and animal production practices that will, over the long term:

- enhance environmental quality and the natural resource base upon which agricultural economy depends

- make the most efficient use of nonrenewable resources and on-farm resources and integrate, where appropriate, natural biological cycles and controls

- sustain the economic viability of farm operations; and enhance the quality of life for farmers and society as a whole.

One form of sustainable farming is organic agriculture. Organic agriculture was developed as a system for producing food that promotes and enhances biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity. Organic farmers emphasize the use of renewable resources and the conservation of soil and water to enhance environmental quality for future generations. Organic meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy products come from animals that are given no antibiotics or growth hormones. Other organic food is produced without using most conventional pesticides, fertilizers made with synthetic ingredients or sewage sludge, or GMOs.

The organic food movement has been endorsed by the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization, which maintains that organic farming fights hunger, tackles climate change, and is good for farmers, consumers, and the environment. The strongest benefits of organic agriculture are its use of resources that are independent of fossil fuels, are locally available, incur minimal environmental stresses, and are cost effective.

Now, outside of indigenous communities, sustainable and organic methods of farming have become an integral component of many government, commercial, and non-profit research efforts, and it is beginning to be woven into agricultural policy.

A most recent framework for sustainable agriculture is regenerative agriculture, a set of farming and grazing practices that reverse climate change by rebuilding soil organic matter and restoring degraded soil biodiversity. This results in both carbon drawdown and improving the water cycle. Watch the 6:53-minute video, “What is Regenerative Agriculture?”. What do you hear farmers share about its origins and what it means to them?

Figure 9.45. “What is Regenerative Agriculture?” (Video)

9.5.3.1 Going Deeper

For more information about the Haudenosaunee confederation see their web site and this 2:38-minute video, “The Haudenosaunee”.

For more information on the value of restorative practices, read the excerpt from a proposal below. The author is Brendan McNamara of the Global Repair Foundation. You can read the full proposal here. Global Earth Repair Foundation

|

An Excerpt from: “Climate Healing: Allying with the Ecosystem to Restore Natural Hydrological and Atmospheric Cycles” 16 December, 2022, Brendan M. McNamara Climate restoration should not come at the cost of human thriving and abundance. Thankfully, we can have our transformation and eat it too – literally – since regenerative agriculture techniques have a way of also providing abundant, nutritious, diverse food. Production of food in this way leads to more resilience in the food system, with a vast and rapidly growing network of farmers connecting their skills and wares to each other and their customers – a hungry world with a growing population. A great many of these techniques, rather than using up organic materials and nutrients, actively help to accumulate them in the soils. Ideally, in a connected, well-planned and well-managed agroecology operation, the animals operate in harmony with the plants, the orchards and fields blend with the paddocks, and the overall health of the land cycles up, not down. All-the-while, on the margins and medians, you can see creeping in here and there the fuzzy green edge of nature. This list is sure to make you feel inspired – or hungry – depending on if you’re reading on an empty stomach: (original list has been abridged and photo added)

|

9.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Social Movements and the Environmental Crisis

“Social Movements and the Environmental Crisis” is written by Aimee Samara Krouskop licensed under CC BY 4.0. “Frontier Ethic”, “Land Ethic” and “Environmental equity”, and “Sustainability” are adapted from sections published in Essentials of Environmental Science by Kamala Doršner, licensed under CC BY 4.0 and modified from the original by Matthew R. Fisher. Edits made for clarification. Images have been replaced and added.

Figure 9.41. The 1872 painting by John Gast, “American Progress” is found on Wikimedia licensed under Public Domain.

Figure 9.42. Aldo Leopold with quiver and bow seated on rimrock above the Rio Gavilan is published on Wikipedia under Public Domain.

Figure 9.43. Linkable image to “The Relationship between Humans and Nature | Native America: Nature to Nations” (video) is found on the same PBS Learning Media page and published here under Fair Use.

Figure 9.45. “What is Regenerative Agriculture?” (Video) is published on YouTube.

Figure 9.46. A reconstruction of Aztec chinampas is provided by JORboney and published on Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 4.0.

Image Description for Figure 9.44:

Shift from Current Worldview to Encouraged Worldview by Social-Environmental Movement

This infographic demonstrates how current ideologies can move to new worldviews with a social-environmental shift.

|

Current Worldview |

Worldview Possible with Social-Environmental Shift |

|---|---|

|

Frontier Ethic: Assumes that the earth has an unlimited supply of resources. If resources run out in one area, more can be found elsewhere or alternatively human ingenuity will find substitutes. |

Sustainability: Living within the means of the earth without significantly impairing its function. |

|

Ego Mindset: Allows us to create hierarchies whether between humans and other species or humans and other human |

Eco Mindset: We see ourselves as part of a whole |

|

Anthropocentric mindset: The belief that humans are the central and most important existence in the universe. |

Cosmo-centric Mindset: Holds in highest importance the universe or nature, and sees all in existence as connected in equilibrium. |