Chymotrypsin

We will begin with mechanism of action of one enzyme – chymotrypsin. Found in our digestive system, chymotrypsin’s catalytic activity is cleaving peptide bonds in proteins and it uses the side chain of a serine in its mechanism of catalysis. Many other protein-cutting enzymes employ a very similar mechanism and they are known collectively as serine proteases (Figure 4.52).

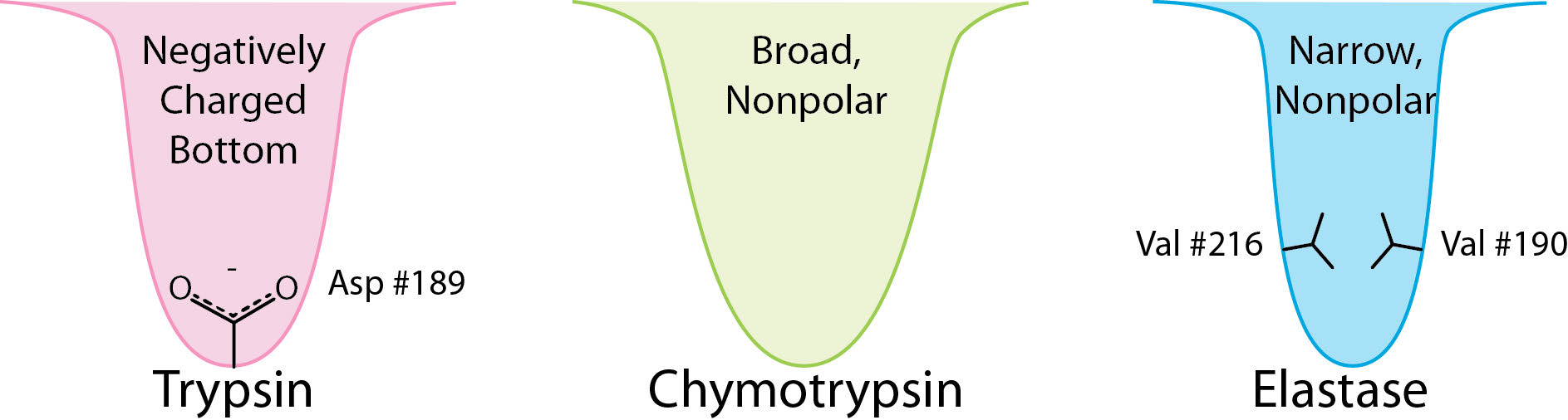

Figure 4.52 – Substrate binding sites (S1 pockets) of three serine proteases. Image by Aleia Kim

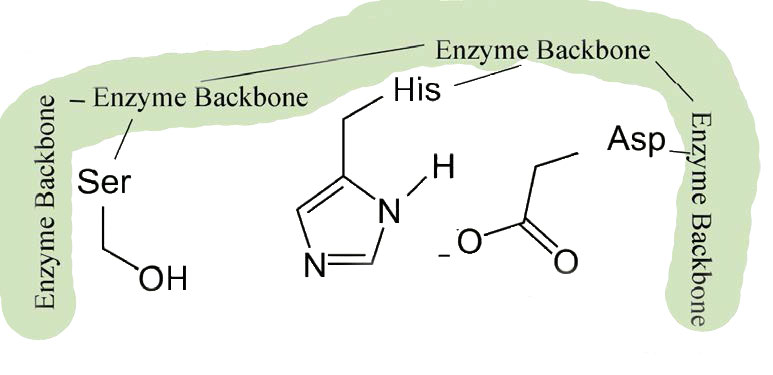

These enzymes are found in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells and all use a common set of three amino acids in the active site called a catalytic triad (Figure 4.53). It consists of aspartic acid, histidine, and serine. The serine is activated in the reaction mechanism to form a nucleophile in these enzymes and gives the class their name. With the exception of the recognition that occurs at the substrate binding site, the mechanism shown here for chymotrypsin would be applicable to any of the serine proteases.

Figure 4.53 – 1. Active site of chymotrypsin showing the catalytic triad of serine – histidine-aspartic acid

Specificity

As a protease, chymotrypsin acts fairly specifically, cutting not all peptide bonds, but only those that are adjacent to relatively non-polar amino acids in the protein. One of the amino acids it cuts adjacent to is phenylalanine. The enzyme’s action occurs in two phases – a fast phase that occurs first and a slower phase that follows. The enzyme has a substrate binding site that includes a region of the enzyme known as the S1 pocket. Let us step through the mechanism by which chymotrypsin cuts adjacent to phenylalanine.

Substrate binding

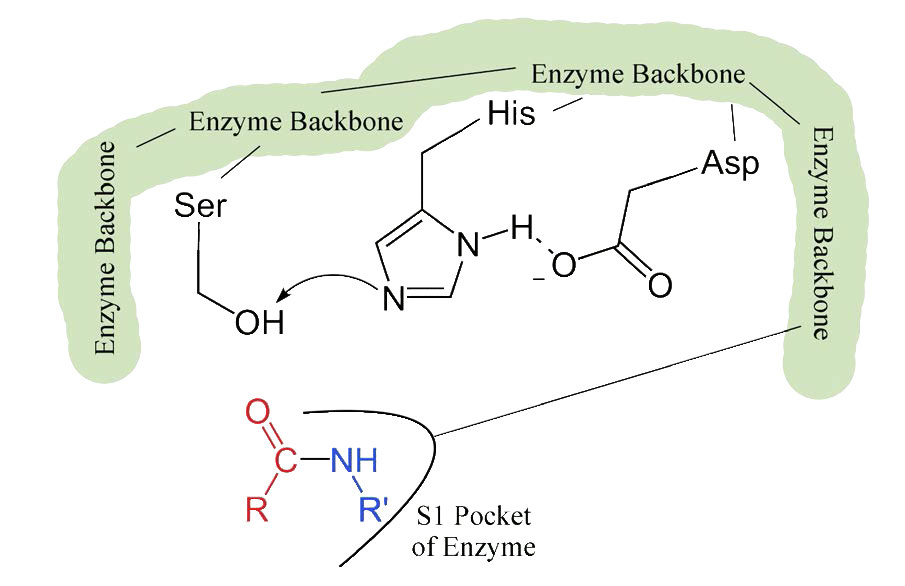

The process starts with the binding of the substrate in the S1 pocket (Figure 4.54). The S1 pocket in chymotrypsin has a hydrophobic hole in which the substrate is bound. Preferred substrates will include amino acid side chains that are bulky and hydrophobic, like phenylalanine. If an ionized side chain, like that of glutamic acid binds in the S1 pocket, it will quickly exit, much like water would avoid an oily interior.

Figure 4.54 – 2. Binding of substrate to S1 pocket in the active site

Shape change on binding

When the proper substrate binds in the S1 pocket, its presence induces an ever so slight change in the shape of the enzyme. This subtle shape change on the binding of the proper substrate starts the steps of the catalysis. Since the catalytic process only starts when the proper substrate binds, this is the reason that the enzyme shows specificity for cutting at specific amino acids in the target protein. Only amino acids with the side chains that interact well with the S1 pocket start the catalytic wheels turning.

The slight changes in shape involve changes in the positioning of three amino acids (aspartic acid, histidine, and serine) in the active site known as the catalytic triad.

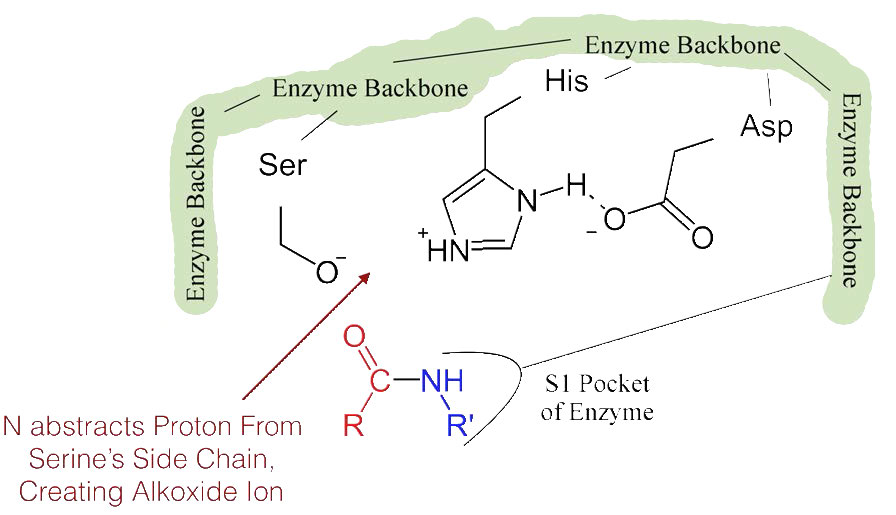

Figure 4.55 – 3. Formation of alkoxide ion

The shift of the negatively charged aspartic acid towards the electron rich histidine ring favors the abstraction of a proton by the histidine from the hydroxyl group on the side chain of serine, resulting in production of a very reactive alkoxide ion in the active site (Figure 4.55).

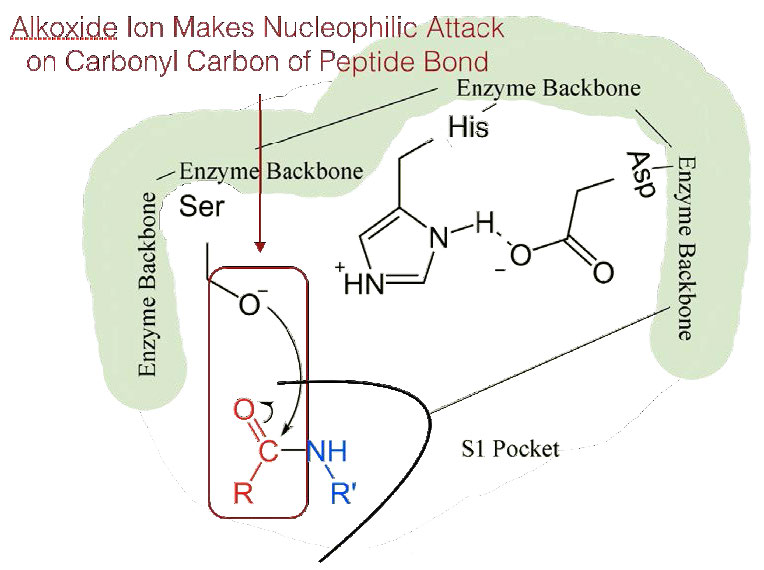

Figure 4.56 – 4. Nucleophilic attack

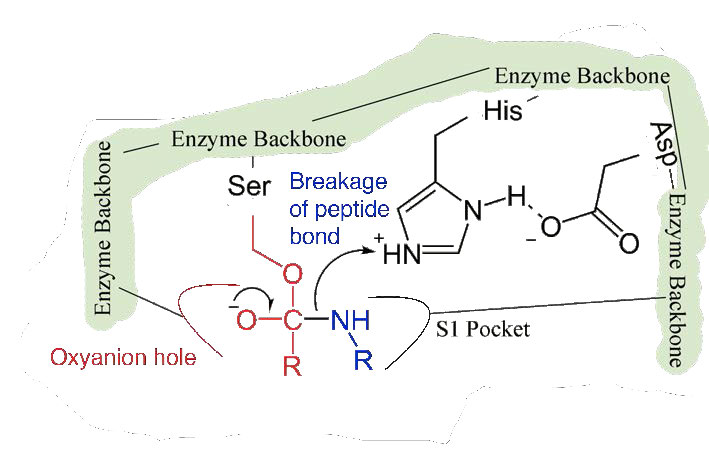

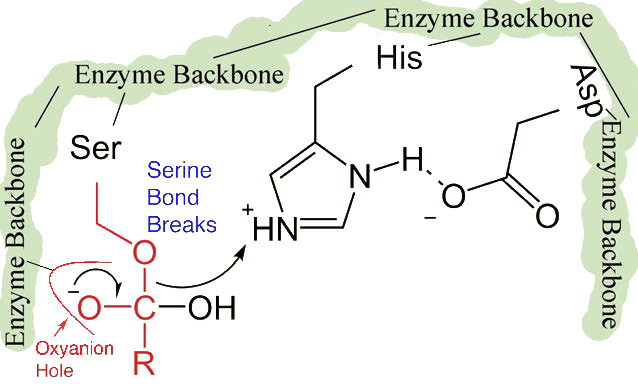

Since the active site at this point also contains the polypeptide chain positioned with the phenylalanine side chain embedded in the S1 pocket, the alkoxide ion performs a nucleophilic attack on the peptide bond on the carboxyl side of phenylalanine sitting in the S1 pocket (Figure 4.56). This reaction breaks the peptide bond (Figure 4.57) and causes two things to happen.

Figure 4.57 – 5. Stabilization by oxyanion hole. Breakage of peptide bond.

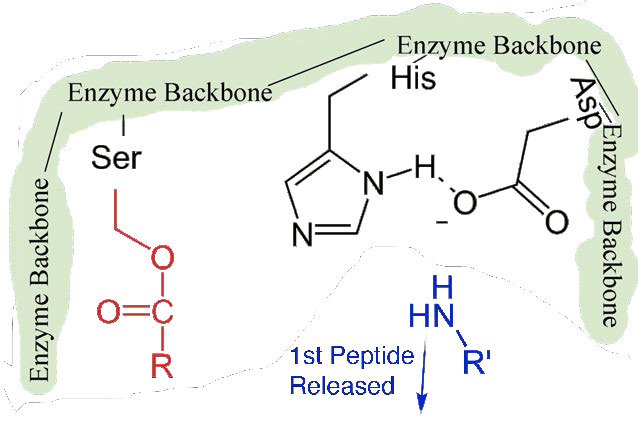

First, one end of the original polypeptide is freed and exits the active site (Figure 4.58). The second is that the end containing the phenylalanine is covalently linked to the oxygen of the serine side chain. At this point we have completed the first (fast) phase of the catalysis.

Figure 4.58 – 6. First peptide released. Other half bonded to serine.

Slower second phase

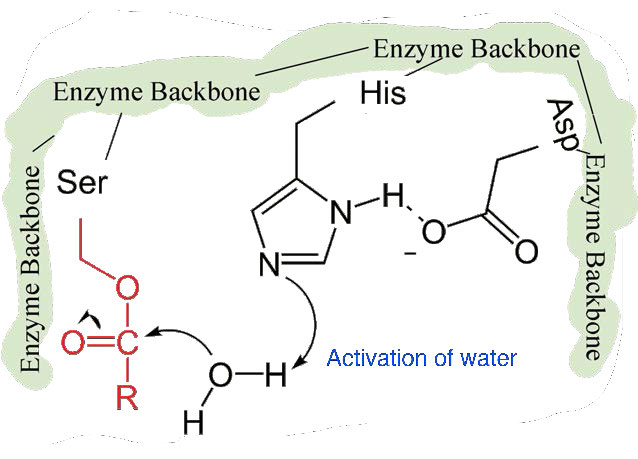

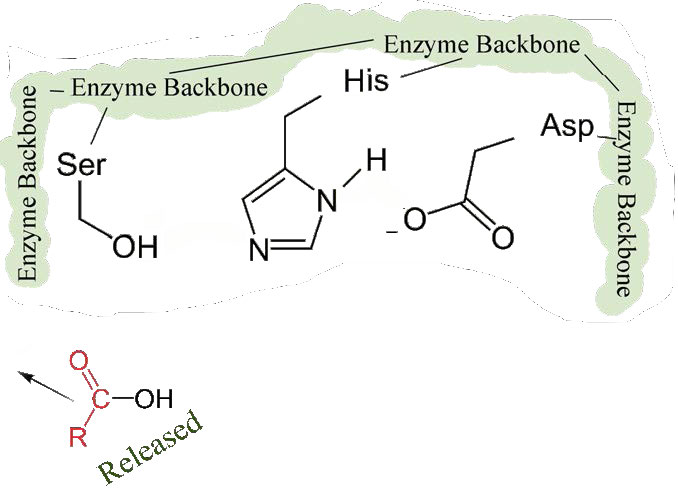

The second phase of the catalysis by chymotrypsin is slower. It requires that the covalent bond between phenylalanine and serine’s oxygen be broken so the peptide can be released and the enzyme can return to its original state. The process starts with entry of water into the active site. Water is attacked in a fashion similar to that of the serine side chain in the first phase, creating a reactive hydroxyl group (Figure 4.59) that performs a nucleophilic attack on the phenylalanine-serine bond (Figure 4.60), releasing it and replacing the proton on serine. The second peptide is released in the process and the reaction is complete with the enzyme back in its original state (Figure 4.61).

Figure 4.59 – 7. Activation of water by histidine

Figure 4.60 – 8. Nucleophile attack by hydroxyl creates tetrahydryl intermediate stabilized by oxyanion hole. Bond to serine breaks.

Figure 4.61 – 9. Second half of peptide released. Enzyme active site restored.

Serine proteases

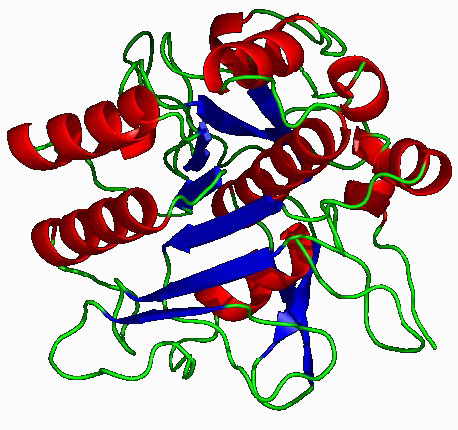

The list of serine proteases is quite long. They are grouped in two broad categories – 1) those that are chymotrypsin-like and 2) those that are subtilisin-like. Though subtilisin-type and chymotrypsin-like enzymes use the same mechanism of action, including the catalytic triad, the enzymes are otherwise not related to each other by sequence and appear to have evolved independently. They are, thus, an example of convergent evolution – a process where evolution of different forms converge on a structure to provide a common function.

The serine protease enzymes cut adjacent to specific amino acids and the specificity is determined by the size/shape/charge of amino acid side chain that fits into the enzyme’s S1 binding pocket (Figure 4.62).

Figure 4.62 – Subtilisin – A serine protease

Examples of serine proteases include trypsin, chymotrypsin, elastase, subtilisin, signal peptidase I, and nucleoporin. Serine proteases participate in many physiological processes, including blood coagulation, digestion, reproduction, and the immune response.

Metalloproteases

Metalloproteases (Figure 4.64) are enzymes whose catalytic mechanism for breaking peptide bonds involves a metal. Most metalloproteases use zinc as their metal, but a few use cobalt, coordinated to the protein by three amino acid residues with a labile water at the fourth position. A variety of side chains are used – histidine, aspartate, glutamate, arginine, and lysine. The water is the target of action of the metal which, upon binding of the proper substrate, abstracts a proton to create a nucleophilic hydroxyl group that attacks the peptide bond, cleaving it (Figure 4.64). Since the nucleophile here is not attached covalently to the enzyme, neither of the cleaved peptides ends up attached to the enzyme during the catalytic process. Examples of metalloproteases include carboxypeptidases, aminopeptidases, insulinases and thermolysin.

Figure 4.64 – Carboxypeptidase – A metalloprotease

Protease inhibitors

Molecules which inhibit the catalytic action of proteases are known as protease inhibitors. These come in a variety of forms and have biological and medicinal uses. Many biological inhibitors are proteins themselves. Protease inhibitors can act in several ways, including as a suicide inhibitor, a transition state inhibitor, a denaturant, and as a chelating agent. Some work only on specific classes of enzymes. For example, most known aspartyl proteases are inhibited by pepstatin. Metalloproteases are sensitive to anything that removes the metal they require for catalysis. Zinc-containing metalloproteases, for example, are very sensitive to EDTA, which chelates the zinc ion.

One category of proteinaceous protease inhibitors is known as the serpins. Serpins inhibit serine proteases that act like chymotrypsin. 36 of them are known in humans.

Serpins are unusual in acting by binding to a target protease irreversibly and undergoing a conformational change to alter the active site of its target. Other protease inhibitors act as competitive inhibitors that block the active site.

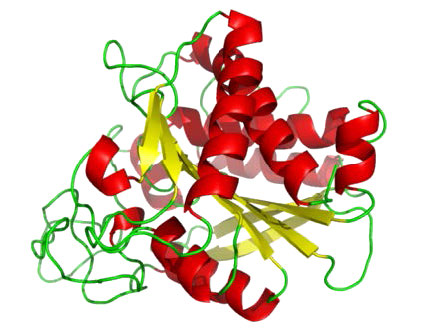

Serpins can be broad in their specificity. Some, for example, can block the activity of cysteine proteases. One of the best known biological serpins is α-1-anti-trypsin (A1AT – Figure 4.66) because of its role in lungs, where it functions to inhibit the elastase protease. Deficiency of A1AT leads to emphysema. This can arise as a result of genetic deficiency or by cigarette smoking. Reactive oxygen species produced by cigarette smoking can oxidize a critical methionine residue (#358 of the processed form) in A1AT, rendering it unable to inhibit elastase. Uninhibited, elastase can attack lung tissue and cause emphysema. Most serpins work extracellularly. In blood, for example, serpins like antithrombin can help to regulate the clotting process.

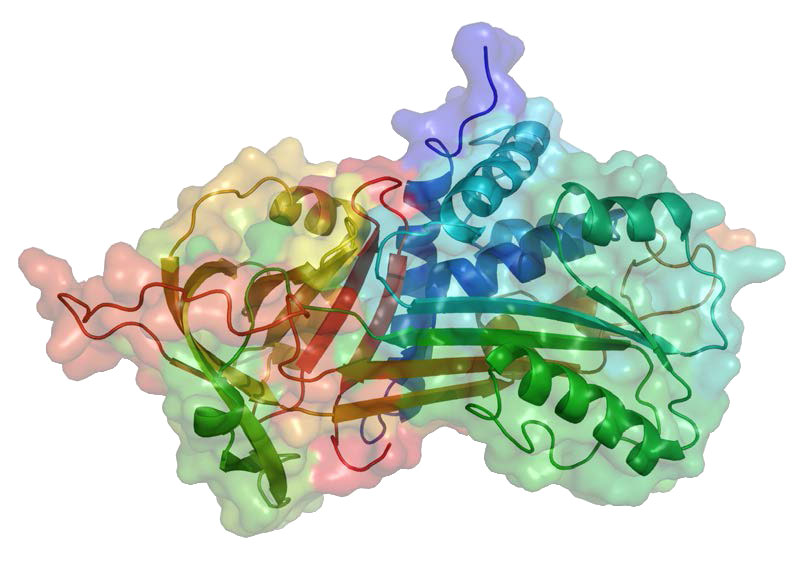

Figure 4.66 – α-1-antitrypsin

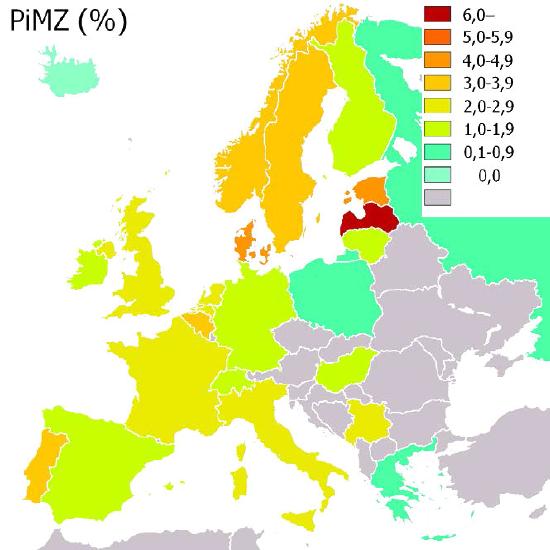

Figure 4.67 – Incidence of α-1-antitrypsin (PiMZ) deficiency in Europe by percent. Wikipedia

Anti-viral Agents

Protease inhibitors are used as anti-viral agents to prohibit maturation of viral proteins – commonly viral coat proteins.

They are part of drug “cocktails” used to inhibit the spread of HIV in the body and are also used to treat other viral infections, including hepatitis C. They have also been investigated for use in treatment of malaria and may have some application in anti-cancer therapies as well.