8.3 Jails

As a part of the growth of punishment and society’s desire to remove accused criminals from the community, the “Brick and Mortar” correctional facility was born. These facilities are called by different names, such as jails, detention centers, prisons, penitentiaries, or camps, but their purpose is the same. Correctional facilities are secure buildings that are used to house or incarcerate individuals accused of or convicted of criminal offenses. The individual’s age, gender, status with the courts, the criminal offense, the jurisdiction, and length of punishment will determine which correctional facility they are housed in. In the coming sections, you will learn about some of these facilities and their role in the criminal justice system.

8.3.1 A Brief History of Jails in the United States

A jail is a place in which individuals accused or convicted of crimes are held. The concept of a jail was brought from Western Europe when the U.S. criminal justice systems were first formed. Influenced by the county-level establishment and management of jails in England, American facilities have largely been run by county sheriffs and have been called various things depending on their function and use, such as bridewells, and workhouses. Figure 8.5. shows the Walnut Street Jail in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which was the first structure built to house individuals who had been processed through the courts. Opened around 1790, this facility housed both pretrial custodies and convicted individuals. It was a blueprint for later prison construction, which we will discuss later in this chapter.

Figure 8.5. Goal in Walnut Street Philadelphia Birch’s views plate 24 (cropped).

As the United States’ population began to expand, county lines were drawn and county jails flourished. Sheriffs began to police their counties and were responsible for managing the low-level infractions within their jurisdictions. Many jails were nothing more than parts of a sheriff’s office, literally cells in the back room. Today, large structures constitute jails in the United States.

While the number of jails in America has changed over the years, in 2019, there were roughly 2,850 jails in the United States according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (Zeng et al., 2021). Some jails are managed by cities or jurisdictions. For example, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., all manage their own jails. A growing trend in some areas are the additions of city-run jails in smaller communities as well. One example of this is the city of Springfield, Oregon. In response to the Lane County Jail budget reductions and reduced capacity, Springfield built their own facility and staffed it with certified officers. They hold individuals with lower-level offenses instead of releasing them back into the community prior to their court appearances, as their county jail was having to do.

8.3.2 Facility Size, Design and Supervision Models

Jails vary greatly in design, function, and size. The vast majority of jails hold less than 50 individuals. The 50 largest jails hold over half of the total number of individuals incarcerated in the U.S., more than 350,000 individuals (Minton, 2021). One example of these larger jails is the Los Angeles County Jail. It is actually a system of buildings spread across Los Angeles County, including an Inmate Reception Center, Century Regional Detention Facility, Men’s Central Jail and the Twin Towers Correctional Facility, just to name a few of their facilities.

Jails also vary in physical design. The two main types of facility design models are the older generation, or linear design, and the newer generation, or podular design. The linear-design facilities were built with space efficiency in mind. Made up of long hallways with cells lining the massive corridors, they hold numerous individuals in a small area of space. In larger facilities, multiple floors hold these long corridors, expanding the number of individuals who can be housed there. Figure 8.6. shows the linear style of jail. Although utilizing every square foot of space efficiently for their design, these types of facilities are not as effective in their supervision of the individuals housed within them as the officers and staff are required to travel down the hallways to each individual cell in order to observe and supervise the occupants of the space.

Figure 8.6. Department of Youth Services Facility showing the long linear corridor with cells on either side.

The podular-design facilities are built with more of a communal living feel. Multiple cells face toward a central living space, allowing an officer to be in the middle of the unit and see the majority of the occupants of the cells around them. It also has common-living areas where socialization and supervision can take place, as seen in figure 8.7.

Figure 8.7. Image of a Podular Designed Pod (cropped). In the image, the officer’s operational booth or desk (immediate right) is open to access the day area or common area, and the doors of the cells open to the shared space.

Figure 8.7. Image of a Podular Designed Pod (cropped). In the image, the officer’s operational booth or desk (immediate right) is open to access the day area or common area, and the doors of the cells open to the shared space.

Along with the different physical design models there are also different types of supervision styles employed within jail facilities. The two main styles of supervision are direct and indirect supervision. The direct supervision style requires an officer to be stationed within the living unit, working with the individuals housed in it, without any barriers. Officers’ roles are to interact with the individuals housed in the unit, supervising their daily activities. In the indirect supervision style, officers are stationed in a control room or away from the unit, separate from where those housed in the unit are. Officers can visually monitor individuals through glass windowed barriers or surveillance cameras but they have to leave their work station and enter through secured doors to enter and interact with the individuals housed in the unit/cells.

8.3.2.1 Dig Deeper

To learn more about these types of facility designs, supervision styles and some pros and cons of each, watch the video from the National Institute of Corrections: NIC—Jails in America: A Report on Podular Direct Supervision.

8.3.3 Who Goes to Jail?

One of the more fascinating aspects of jails in the United States is who gets placed in them. The short answer is everyone. Whenever someone is arrested, jail starts their process in the criminal justice system. Jails are a collection point for many agencies, including arrests made by municipal city police, county sheriff’s offices, state police, and even federal agencies may use a local jail as a point of entry. For example, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) houses many thousands of individuals pending immigration related charges in jails across the country. While this list is not comprehensive, it does present many of the types of people held in jails:

- Individuals arrested for felony and misdemeanor crimes

- First-time and repeat offenders

- Individuals awaiting arraignment or trial

- Individuals who are accused and convicted

- Parolees leaving prison

- Juveniles pending transfer

- Individuals with mental illness awaiting transfer

- Chronic alcoholics and drug abusers

- Individuals held for the military

- Individuals held for federal agencies

- Protective custody

- Material witnesses

- Individuals in contempt of court

- Persons awaiting transfer to state, federal or other local authorities

- Temporarily detained persons

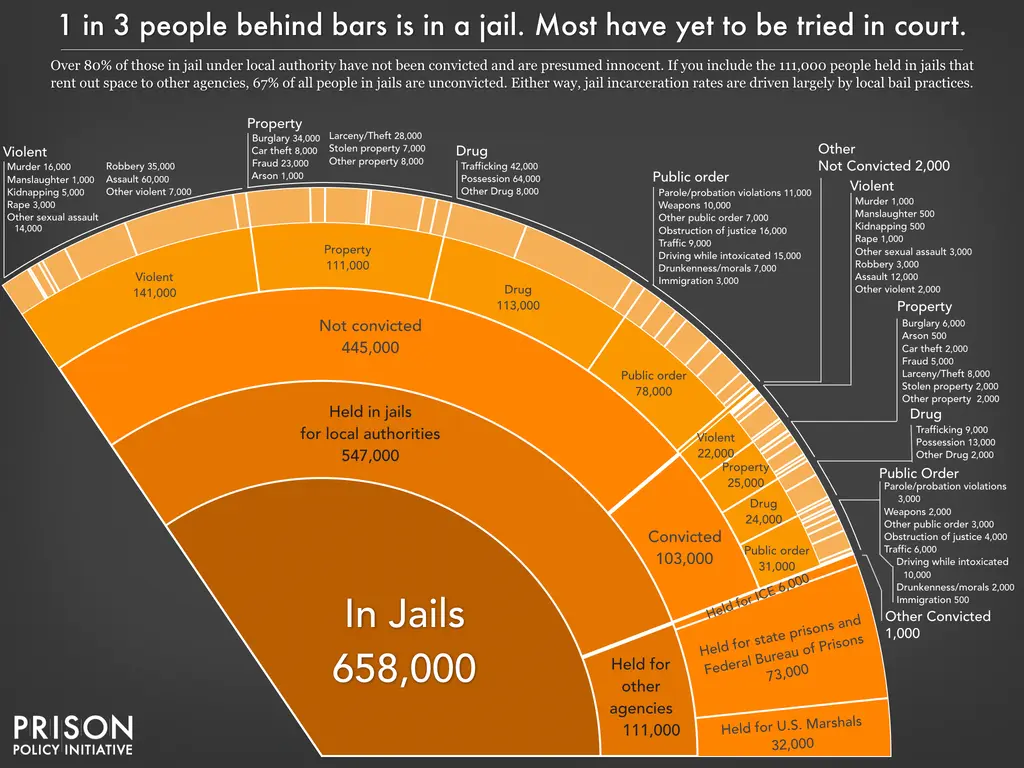

At any given point in time, there are approximately 650,000 to 750,000 individuals held in jails in the United States. This number has steadily increased since the 1970s. It is estimated that roughly 10 million people process through America’s jails annually (Sawyer & Wagner, 2022). As shown in figure 8.8, the types of people in jail at a single point in time is varied.

Figure 8.8. Graph breaking down the various individuals held within the Jail population.

Probably one of the most notable items in the snapshot above is the proportions of individuals that are not convicted. Roughly 68 percent of individuals in jails at any given time are not convicted. Other notable groups are individuals held for other agencies. This could be a matter of processing time or allocations of bed space. Still, jails only make up one portion of the brick-and-mortar approach to punishment. Prisons are the other large part.

8.3.4 Life and Culture in Jail

With the rise of popular television series like 60 Days In, the view of everyday life inside the walls of a jail can be skewed. Jails stick to a daily schedule of serving meals and managing unit activities for those who are eligible including cleaning shared and individual spaces, recreation time, attending court appearances, programs, and work or educational opportunities. The majority of individuals inside the walls follow the daily routine and take advantage of telephone calls, visiting opportunities and recreation privileges, while others choose to remain in their cells the majority of the day and read books, write letters, or sleep. The intake, behavioral health, and segregation units are the areas which see the most activity. Individuals still under the influence of substances or struggling with mental health issues can be found, at times, yelling out of their individual cells at those in the surrounding areas.

8.3.4.1 Rights and Privileges

Individuals housed in jails maintain some rights and are afforded some privileges but not as many as those housed in prisons. They have constitutional rights to be free from discrimination, to access the courts and counsel, of speech, of religious freedom when it doesn’t impede safety and security, to due process, and to be protected from cruel and unusual punishment. They are also entitled to protections under the Americans with Disabilities Act and, in some cases, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

8.3.4.2 Dig Deeper

To learn more about individuals rights of those incarcerated, visit Know Your Rights | Prisoners’ Rights | American Civil Liberties Union.

They receive three meals a day, clothing, and basic toiletries. They have access to a place to sleep, sit, exercise, shower, and use the bathroom, but they lose their rights to privacy when it comes to having their personal items searched at any time. Officers have the ability to pat them down and search their cells. Privileges like the ability to purchase additional food, clothing, and toiletry items are earned, incentivizing good behavior.

8.3.4.3 Program and Work Opportunities

Additional privileges are provided depending on the facility’s resources. Some jails provide options to participate in short-term education and treatment programs like General Education Development (GED), Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), and Narcotics Anonymous (NA). Various religious organizations have representatives who also run optional services and programs for individuals to attend like Catholic Prayer Services, Jehovah’s Witness Bible Studies, and Prison Fellowship.

Working within the facilities is an option as well, although most jails do not pay the incarcerated individuals for their work, as it is seen as a privilege and optional. Some states like Oregon have implemented “worker time” which allows, sentence eligible, individuals to get time off their sentence for working, allowing them to be released from custody sooner in compensation for their efforts.

8.3.5 Licenses and Attributions for Jails

“Jails” by Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “8.7. A Brief History of Prisons and Jails”, “8.8. Types of Jails”, and “8.9. Who Goes to Jail?” by David Carter in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Edited for style, consistency, recency, and brevity; added DEI content.

Figure 8.5. Goal in Walnut Street Philadelphia Birch’s views plate 24 (cropped) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 8.6. DYS Facility cisco.png—Wikimedia Commons by Freeatlastchitchat is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 8.7. Direct Supervision (Podular) (cropped) from the Houma Times is included under fair use.

Figure 8.8. 1 in 3 people behind bars is in a jail. Most have yet to be tried in court © The Prison Policy Initiative. All Rights Reserved, Used with permission materials.