11

Emilie Miller, Ph.D

Growing bacteria in culture requires consideration of their nutritional and physical needs. Food, provided in the media, is broken down by cells and used for energy and building biomass. Unlike eukaryotic cells, bacteria have options when it comes to making energy, which depend not only on the type of organic molecules in the food but also on the availability of oxygen as a final electron acceptor for respiration.

Respiration is the pathway in which organic molecules are sequentially oxidized to strip off electrons, which are then deposited with a final electron acceptor. Along the way, ATP is made. For many types of bacteria, oxygen serves as the final electron acceptor in respiration. Remarkably, oxygen is not always a requirement for respiration. For bacteria that live in environments with no air, alternative electron acceptors may take the place of oxygen.

Unlike the majority of eukaryotes, bacteria have options when it comes to making ATP. Aerobic respiration and anaerobic respiration generate ATP by chemiosmosis, and some bacteria may also ferment sugars, although the oxidation is not complete and energy is left behind. Chemical by-products and end products of these pathways are detectable and serve as the basis for many biochemical tests performed to identify bacteria.

Fermentation and anaerobic respiration are anaerobic processes—meaning that no oxygen is required for ATP production. Some bacteria have the capability (meaning they produce the appropriate enzymes) to use more than one, or even all three, of these pathways depending on growth conditions.

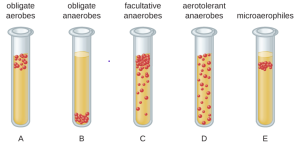

Based on whether oxygen is required for growth, bacteria can be considered to be either aerobes or anaerobes. However, because some bacteria may use more than one pathway, there are additional categories that describe a culture’s requirement for oxygen in the atmosphere. The three major categories are:

Strict aerobe—Bacteria that are strict aerobes must be grown in an environment with oxygen. Typically, these bacteria rely on aerobic respiration as their sole means of making ATP, but some may also ferment sugars.

Strict anaerobe—These bacteria live only in environments lacking oxygen, using anaerobic respiration or fermentation to survive. For these types of cells, oxygen can be lethal because they lack normal cellular defenses against oxidative stress (enzymes that protect cells from oxygen free radicals).

Facultative anaerobe—The most versatile survivalists there are. These bacteria typically have access to all three ATP-forming pathways, along with the requisite enzymes to protect cells from oxidative stress.

Additionally, overlapping categories include:

Microaerophile—As the name implies, these bacteria prefer environments with oxygen, but at lower levels than normal atmospheric conditions. Often, microaerophiles also have a requirement for increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and may also be called capnophiles. These bacteria make ATP by aerobic respiration and may also ferment sugars aerobically.

Aerotolerant anaerobe—These bacteria make ATP by anaerobic respiration and may also be fermentive. However, they are “tolerant” of oxygen because they may have cellular defenses against oxygen free radicals.