4.4 Research tools

Databases

Very often, you will want articles on your topic, and the easiest way to find articles is to use a research database – a specialized search engine for finding articles and other types of content. For example, if your topic is residential solar power, you can use a research database to look in thousands of journal titles at once and find the latest scientific and technical research articles – articles that don’t always show up in your Google searches. Depending on the database you are using, you might also find videos, images, diagrams, or e-books on your topic, too. Most databases require subscriptions for access; check with your college, public, or corporate library to see what databases they subscribe to for you to use. Whether they are subscription-based or free, research databases contain records of journal articles, documents, book chapters, and other resources and are not tied to the physical items available at any one library. Many databases provide the full-text of articles and can be searched by keyword, subject, author, or title. A few databases provide just the citations for articles, but they usually also provide tools for you to find the full text in another database or request it through interlibrary loan. Databases are made up of records, and records contain fields, as explained below:

- Records: A record describes one information item (e.g., journal article, book chapter, image, etc.).

- Fields: These are part of the record, and they contain descriptions of specific elements of the information item such as the title, author, publication date, and subject.

Another aspect of databases to know about is controlled vocabulary. Look for the label subject term, subject heading or descriptor. Regardless of label, this field contains controlled vocabulary, which are designated terms or phrases for describing concepts. It’s important because it pulls together all of the items in that database about one topic. For example, imagine you are searching for information on community colleges. Different authors may call community colleges by different names: junior colleges, two-year colleges, or technical colleges. If the controlled vocabulary term in the database you are searching is “community colleges,” then your one search will pull up all results, regardless of what term the author uses.

Databases may seem intimidating at first, but you likely use databases in everyday life. For example, do you store contact information in your phone? If so, you create a record for everyone for whom you want to store information. In each of those records, you enter descriptions into fields: first and last name, phone number, email address, and physical address. If you wanted to organize your contacts, you might put them into groups of “work,” “family,” and “friends.” That would be your controlled vocabulary for your own database of contacts.

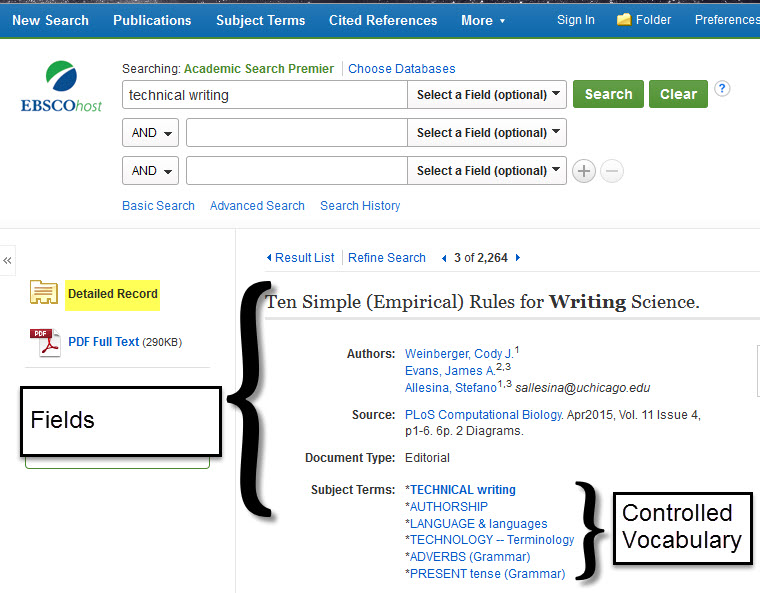

The image below shows a detailed record for a journal article from a common research database, Academic Search Premier. The fields and controlled vocabulary are labeled.

Figure 2. Fields and controlled vocabulary

General

Databases that contain resources for many subject areas are referred to as general or multidisciplinary databases. This means that they are good starting points for research because they allow you to search a large number of sources from a wide variety of disciplines. Content types in general databases often include a mix of professional publications, scholarly journals, newspapers, magazines, books, and multimedia.

Common general databases in academic settings include

- Academic Search Premier

- Academic OneFile

- JSTOR

Specialized

Databases devoted to a single subject are known as subject-specific or specialized databases. Often, they search a smaller number of journals or a specific type of content. Specialized databases can be very powerful search tools after you have selected a narrow research topic or if you already have a great deal of expertise in a particular area. They will help you find information you would not find in a general database. If you are not sure which specialized databases are available for your topic, check your library’s website for subject guides, or ask a librarian.

Specialized databases may also focus on offering one specific content type like streaming films, music, images, statistics, or data sets.

Table 4. Examples of specialized databases and their subject focus

| Database | Subject Focus |

| PsycInfo | Psychology |

| BioOne | Life Sciences |

| MEDLINE | Medicine/health |

| ARTstor | Fine arts images |

Library catalogs

A library catalog is a database that contains all of the items located in a library as well as all of the items to which the library offers access, either in physical or online format. It allows you to search for items by title, author, subject, and keyword. Like research databases, library catalogs use controlled vocabulary to allow for powerful searching using specific terms or phrases.

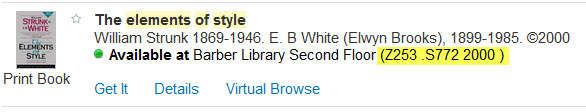

If you locate a physical item in a catalog, you will need the call number to find the item in the library. A call number is like a street address for a book; it tells you exactly where the book is on the shelf. Most academic libraries will use the Library of Congress classification system, and the call numbers start with letters, followed by a mix of numbers and letters. In addition to helping you find a book, call numbers group items about a given topic together in a physical place. The image below shows an example of the location of a call number in a library catalog.

Figure 3. A call number in an online library catalog display

Along with physical items, most libraries also provide access to scholarly e-books, streaming films, and e-journals via their catalogs. For students and faculty, these resources are usually available from any computer, meaning you do not have to go to the library and retrieve items from the shelf.

Consortia and interlibrary loan

In the course of your research you will almost certainly find yourself in a situation where you have a citation for a journal article or book that your institution’s library doesn’t have. There is a wealth of knowledge contained in the resources of academic and public libraries throughout the United States. Single libraries cannot hope to collect all of the resources available on a topic. Fortunately, libraries are happy to share their resources and they do this through consortia membership and interlibrary loan (ILL). Library consortia are groups of libraries that have special agreements with one another to loan materials to one another’s users. Both academic and public libraries belong to consortia.

Central Oregon Community College (COCC) belongs to a consortium of 37 academic libraries in the Pacific Northwest called the Orbis Cascade Alliance, which sponsors a shared lending program called Summit. When you search the COCC Library Catalog, your results will include items from other Summit institutions, which you can request and have delivered to the COCC campus of your choice.

Interlibrary loan (ILL) allows you to borrow books, articles and other information resources regardless of where they are located. If you find an article when searching a database that COCC doesn’t have full text access to, you can request it through the interlibrary loan program. If you cannot get a book or DVD from COCC or another Summit library, you could also request it through interlibrary loan. Interlibrary loan services are available at both academic and public libraries.

Government information

Another important source of information is the government. Official United States government websites end in .gov and provide a wealth of credible information, including statistics, technical reports, economic data, scientific and medical research, and, of course, legislative information. Unlike research databases, government information is typically freely available without a subscription.

USA.gov is a search engine for government information and is a good place to begin your search, though specialized search tools are also available for many topics. State governments also have their own websites and search tools that you might find helpful if your topic has a state-specific angle. If you get lost in searching government information, ask a librarian for help. They usually have special training and knowledge in navigating government information.

Table 5. Examples of specialized government sources and their subject focus

| Specialized Government Source | Subject Focus |

| PubMed Central | Medicine/health |

| ERIC | Education |

| Congress.gov | Legislation and the legislative process |

Experts

People are a valuable, though often overlooked, source. This might be particularly appropriate if you are working on an emerging topic or a topic with local connections.

For personal interviews, there are specific steps you can take to obtain better results. Do some background work on the topic before contacting the person you hope to interview. The more familiarity you have with your topic and its terminology, the easier it will be to ask focused questions. Focused questions are important for effective research. Asking general questions because you think the specifics might be too detailed rarely leads to the best information. Acknowledge the time and effort someone is taking to answer your questions, but also realize that people who are passionate about subjects enjoy sharing what they know. Take the opportunity to ask experts about additional resources they would recommend.

Chapter Attribution Information

Research Tools derived by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, Central Oregon Community College, from The Information Literacy User’s Guide edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0 US