1.4 Theories and Practices Central to Human Services

The introduction to this chapter is based on the work of Aika Fricke, while she was a candidate for her MSW at Ferris State University (figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Aikia Fricke graduated in 2006 and wrote the basis for this chapter introduction while an MSW candidate at Ferris State University.

Aika Fricke has worked for Community Mental Health for Central Michigan since 2008, working as a clubhouse advocate, case manager, and most recently as an employment specialist. She obtained a BSW at Ferris State University in 2006, and wrote the basis for this chapter while an MSW candidate at Ferris State University. She is a full-time mother to “four lovely children and a full-time wife to a wonderful and very supportive husband, as without his tremendous support furthering my education would not have been possible.”

1.4.1 A Generalist Approach

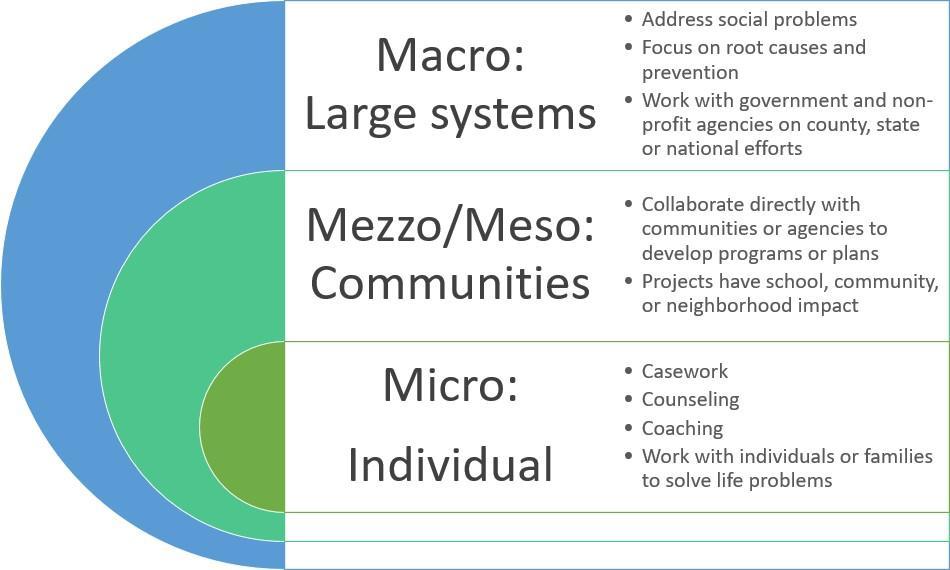

Human services professionals take a generalist approach, which means they use their broad knowledge across many disciplines and methods to solve problems. An advantage of the generalist approach is the awareness of theories, foundational concepts, and practices of multiple fields and practitioners that promote well-being. A generalist approach introduces students to the application of addressing social problems at the individual (micro), group (mezzo), and community (macro) levels while following ethical principles and critical thinking (Inderbitzen, 2014). Generalist human services workers in a helping profession use a wide range of prevention, intervention, and remediation methods when working with families, groups, individuals, and communities to promote human and social well-being (Johnson & Yanca, 2010).

Being a generalist practitioner prepares you to enter nearly any profession within the human services and social work fields, depending on your population of interest (Inderbitzen, 2014). You may develop a specialty within the generalist approach within your education, internships, or professional life. For example, the director of a program for people experiencing houselessness would apply their generalist knowledge to a specific population, those who have housing insecurity or are houseless. Or a medical social worker would apply their broad knowledge to a specific group of people who are hospitalized or at a cancer center.

1.4.2 Theories and Research

You may feel intimidated by theory. Even the phrase, “Now we are going to look at some theories . . .,” is often met with blank stares. But theories are valuable tools for understanding human behavior. They propose explanations for the “hows” and “whys” of development and behaviors.

Have you ever wondered, “Why is my 3-year-old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?”or “Why do some people become addicted to alcohol and others do not?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Theories offer explanations about how we develop, why we change over time, and what kinds of influences impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to be used to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as guidelines much like directions that come with an appliance or other object that requires assembly. The instructions can help you piece together smaller parts more easily than by trial and error. There are many theories of development. In this book, we have chosen to draw on many theories, several of which are summarized in this chapter.

1.4.2.1 Why Theories and Research Matter

There are many benefits to using theories in research. First, theories provide the underlying logic of the occurrence of natural or social phenomena, such as why some members of a family may have an illness such as anorexia or substance use disorder and others do not. They do this by explaining the key drivers and key outcomes of the target phenomenon and why, and what underlying processes are responsible for driving that phenomenon. Second, they aid in sense-making by helping us synthesize prior research findings within a theoretical framework. In doing so, they help us reconcile seemingly contradictory findings by uncovering variables that influence the relationship between two hypotheses in different studies. Third, theories provide guidance for future research by helping identify constructs and relationships that are worthy of further research. Fourth, theories can build knowledge and bridge gaps between other theories. As a result, they cause us to examine existing theories in a new light.

There are many methods available to researchers in their efforts to understand, describe, and explain behavior and the cognitive and biological processes that underlie it. Some methods rely on observational techniques. Other approaches involve interactions between the researcher and the individuals who are being studied—ranging from a series of simple questions to extensive, in-depth interviews—to well-controlled experiments.

However, theories have their own limitations. As simplified explanations of reality, theories may not always provide adequate explanations of complicated relationships. Theories are designed to be simple and brief explanations, while reality may be significantly more complex. Furthermore, theories may impose blinders or limit researchers’ range of vision, causing them to miss out on important concepts that are not defined by the theory.

While understanding theories, it is also important to understand what theory is not. Theory is not data, facts, or empirical findings. A collection of facts is not a theory, just as a pile of stones is not a house. Likewise, a collection of ideas is not a theory, because theories must go well beyond ideas to include propositions, explanations, and boundary conditions (the who, where, and when aspects of a theory). Data, facts, and findings operate at the observational level, while theories operate at a conceptual level and are based on logic rather than observations.

Theories can be developed using induction, a process in which the theorist observes and notes patterns in a variety of single cases and then develops (“induces”) ideas based on these examples. Established theories are then tested through research; however, not all theories are equally suited to scientific investigation. Some theories are difficult to test but are still useful in stimulating debate or providing concepts that have practical application. Keep in mind that theories are not facts; they are guidelines for investigation and practice, and they gain credibility through research that fails to disprove them.

1.4.2.2 Weaknesses or bias in research

Research bias occurs when the research process is skewed by the behaviors or beliefs of the researcher and/or the participants. Bias is an important issue to pay attention to, for both the researcher and those who rely on research findings to make critical decisions in human services programs. Awareness of bias is an essential step in addressing institutional systems of oppression that affect families. This is particularly important for those who navigate stigmatized identities, such as families of color, low-income families, and members of LGBTQ+ communities, to name a few. Bias in research can influence who participates in research, or whether findings are reliable and valid. Some common biases are listed in the table in figure 1.6.

| Types of Bias | Description and Example |

|---|---|

| Design bias | The study design reflects preferences or preconceived ideas from the researcher.

Example: A drug company researches their own medication and emphasizes the value of the drug in their questions. |

| Publishing bias | Publication requirements exclude certain types of research modalities (e.g., no qualitative studies) or findings that are not statistically significant.

Example: A qualitative study is not published due to lack of statistical findings. |

| Recall bias | Results from studies relying on the memories of participants may be skewed due to inaccuracies in recall.

Example: |

| Selection bias | Participant criteria and inclusion methods exclude some populations from the study.

Example: A researcher collects data about accessing low-income community resources solely through an online survey (low-income families may not have access to the internet). |

Figure 1.7. Types of research bias

1.4.3 Systems Theory

Systems theory is an interdisciplinary study of complex systems that focuses on the dynamics and interactions of people in their environments (Ashman, 2013). Professionals use this theory to identify, define, and address problems within social systems.

Systems thinking helps us understand the relationships between individuals, families, and organizations within our society. It is used to identify how a system functions and how the negative impacts can affect a person, family, organization,or overall society. The same information can be used to identify strengths and to cause a positive impact within that system (Flamand, 2017).

1.4.4 Ecological Systems Theory

The ecological systems theory, created in the late 1970s by Urie Bronfenbrenner, draws on both systems theory and an ecological approach called person-in-environment. Person-in-environment is the idea that people are influenced by their environments.

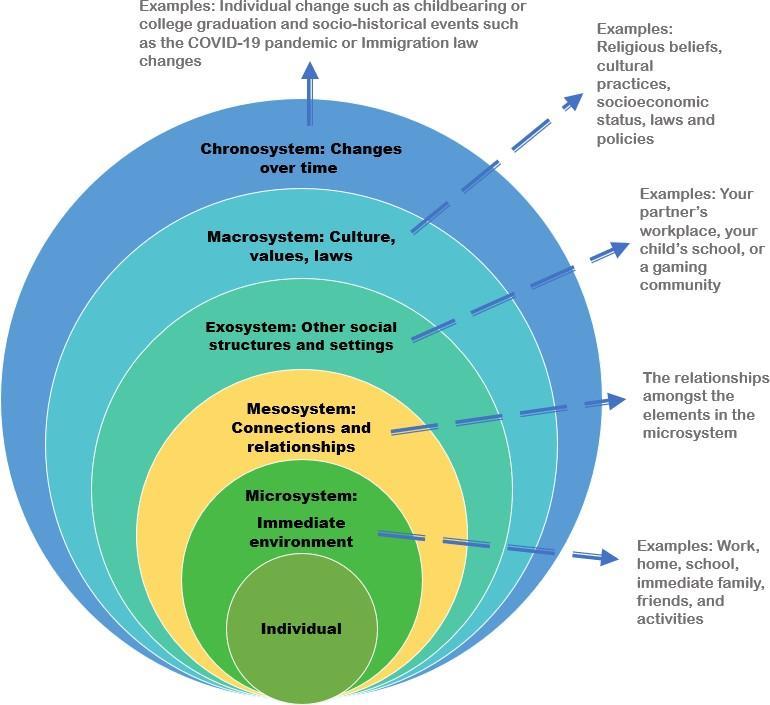

The ecological systems theory emphasizes the complexity of the environments and systems that each individual interacts with. In helping professions, professionals support individuals to identify what is working well and what is negatively impacting them within multiple systems and environments (figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Ecological systems theory shows how the individual is influenced by different systems, from the microsystem to the chronosystem.

To illustrate this theory and the following theory, we will use this vignette about “Marlon.”

Marlon’s parents have been called by the school social worker to discuss concerns related to fighting with a peer and declining grades. His parents also report concerns at home with poor sibling relationships, anger issues, and “a bad attitude, always talking back, never listening or doing what we ask him to do.” They report a long family history of substance abuse and mental health issues (anxiety and depression). They report increased concerns related to this as they recently found marijuana in Marlon’s room. Marlon, 14-years-old, reports, “My parents don’t know what they’re talking about. My little brother and sister just get me in trouble because I don’t let them touch my stuff, besides, my parents don’t care, they don’t listen to me, they just want me to do what they say. And I don’t see what the big deal is with me smoking a little weed, it helps me feel better and not be so mad all the time.”

1.4.4.1 Microsystem

The ecological systems theory is typically illustrated with six concentric circles that represent the individual, environments and interactions (figure 1.x):The microsystem is the smallest system, focusing on the relationship between a person and their direct environment, typically the places and people that the person sees every day. Often this includes parents and school for a child or partner, or work and school for an adult.

Marlon is an adolescent which means his body continues to experience hormonal and physical changes. Within the family, a key element of the microsystem, he is also reported to present with anger, fighting with his siblings and struggling with strained relationships.

Family reports history of substance abuse issues as well as struggles with mental health issues, which may indicate possible genetic connections to be explored.

1.4.4.2 Mesosystem

The mesosystem, which lies between the micro and exo systems, is representative of how those people and places interact and cooperate. If they work together well, it can have a positive effect on the individual. For example, if a student also has a job, is the employer willing to work around the school schedule? If a child goes to a child care program, do the teacher and the parent communicate clearly with each other? The mesosystem is really important because it is about the relationships and the interactions amongst important environments.

Here we would look further into how his relationships and interactions with various groups impact him . It appears that the school and parents have an effective communication system, which is a positive for Marlon’s mesosystem. In addition the mesosystem includes the interactions he might have with a spiritual affiliation/church,community groups or organizations he identifies as part of his exosystem.

1.4.4.3 Exosystem

The exosystem includes the people and places that an individual interacts with on a regular basis but not daily, such as a place of worship, club, lesson, or social group.

Marlon participated in athletics throughout elementary and middle school, but has gradually drifted away from these activities. Exploring other groups or communities that he could connect with would strengthen Marlon’s supports in the exosystem.

1.4.4.4 Macrosystem

The macrosystem identifies the larger values and attitudes of the culture and varies by location and interest.

School policies, mental health policies, healthcare systems, culture and historical impacts of group experiences, drug laws and policies, and possible discrimination and prejudice impacts all need to be explored. In particular, conflicting values and beliefs about the use of marijuana are likely impacting Marlon.

1.4.4.5 Chronosystem

The chronosystem describes time as a system that affects individuals. Large events and trends such as the dramatic increase in college costs and debt, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the dramatic increase in wildfires on the west coast of the United States are all examples of events in the chronosystem that affect individuals and families in the first part of the twenty-first century.

Many adolescents have reported increases in depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s possible that Marlon has been affected and that is related to his use of marijuana. It is important to consider large sociocultural events and their effects on individuals.

1.4.5 Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Approach

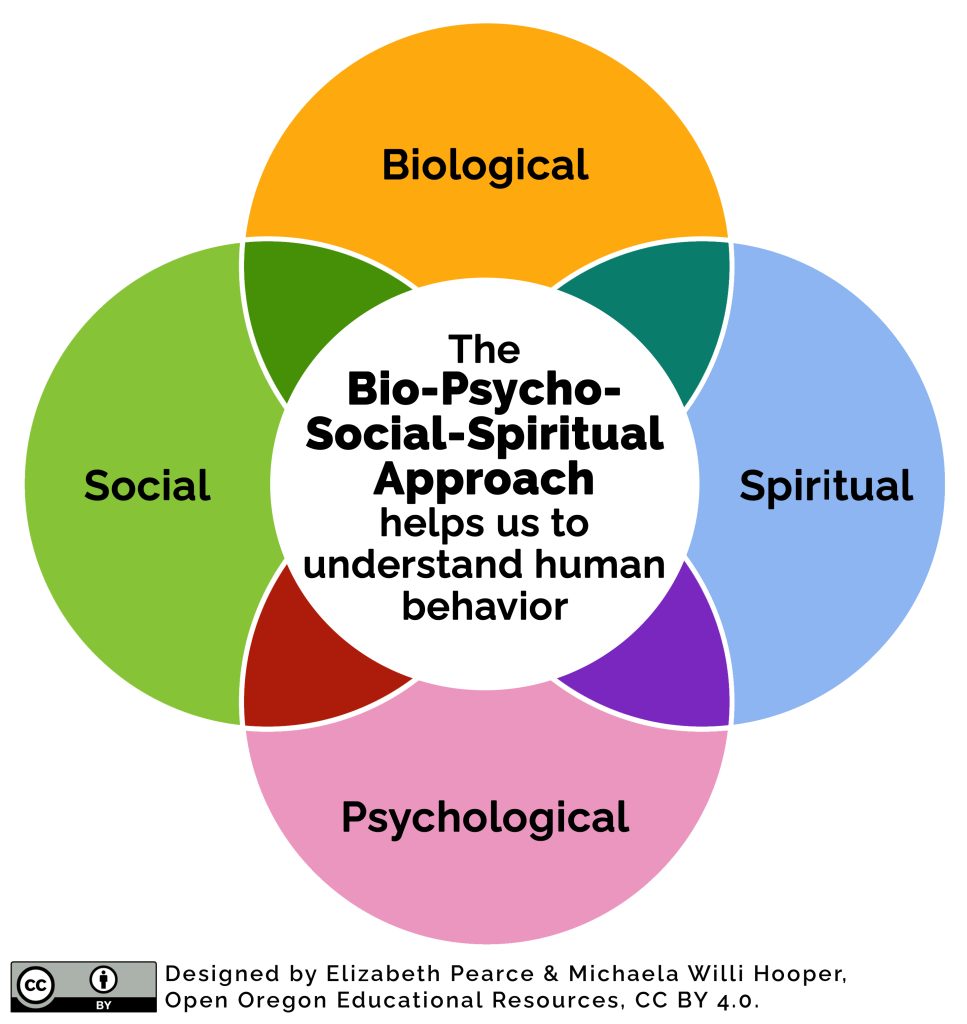

Looking at each dimension of the bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach allows you to engage in a more holistic exploration and assessment of a person as it examines and connects four important domains of their life as illustrated in image 1.9 and defined in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1.9. To better understand someone, consider the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions of their life.

The bio-psycho-social-spiritual approach assesses levels of functioning within biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions (and how they are connected) to help understand human behavior. This approach includes much of the same information you will find in the Micro level but we are wanting to take a deeper look at how the individual is functioning in each dimension as well as how they can impact one another.

1.4.5.1 Biological Component

The biological component includes aspects related to overall health, physical abilities, weight, diet, lifestyle, medication/substance use, gender, and genetic connections/vulnerabilities.

Marlon’s biological aspects – No concerns with overall physical health, developmental aspects of adolescence need to be considered, substance use concerns and impacts, identifies as male, and possible genetic connections/vulnerabilities (substance abuse, anxiety, depression, or any other family history of concern).

1.4.5.2 Psychological Component

The psychological component includes aspects related to mental health, self-esteem, attitudes/beliefs, temperament, coping skills, emotions, learning, memory, perceptions, and personality.

Marlon’s psychological aspects – Anger, substance use concerns and impacts, possible esteem issues, poor coping skills and emotional regulation, cognitive development and any related concerns, personality and temperament characteristics, and explorations of how he perceives his world.

1.4.5.3 Social Component

The social component includes aspects related to peer and family relationships, social supports, cultural traditions, education, employment/job security, socioeconomic status, and societal messages.

Marlon’s social aspects – Strained family relationships, school relationships/educational supports, exploration of socioeconomic impacts, exploration of cultural traditions, and identification/exploration of peer relationships and supports.

1.4.5.4 Spiritual Component

The spiritual component includes aspects related to spiritual or religious beliefs, or belief in a higher being or higher power they feel connected to or supported by.

Marlon’s spiritual aspects – No spiritual aspects were reported but we would want to explore what this means to Marlon. Does he identify with a church, religion, or higher power/being? What does it mean to him? Does it bring any support and comfort or is it causing increased stress as he is working to figure out what it all means?

1.4.6 Evidence-Based Practice

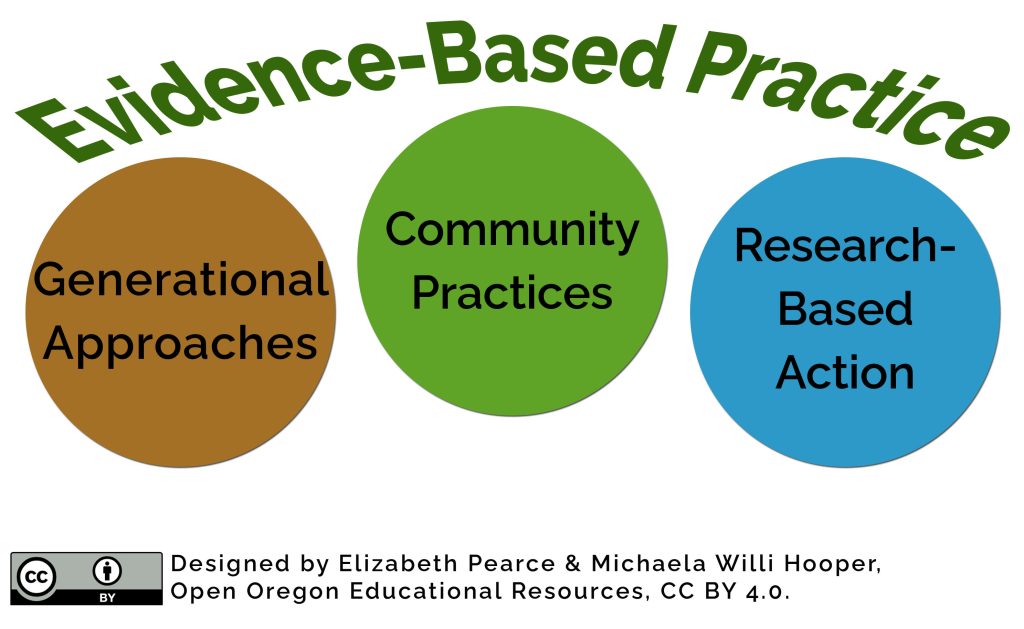

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of a client. When working with clients, combining research and clinical expertise can be of benefit. In the fields of human development and family sciences, sociology, and psychology there is ongoing research being conducted to assess various assessment and treatment modalities. The research that is conducted provides the evidence that professionals use to help our clients improve their living situations and concerns.

At the same time, pay attention to practices used by Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color over centuries of use, such as meditation.Whether or not these practices have been researched and produced formal evidence, the long-time use of these methods is another kind of evidence.

When new social problems emerge, there is a need to combine existing research and knowledge with best practices, and data that is collected by the government and large agencies in present time. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic presents new challenges and has uncovered existing inequities in our labor and health care systems, which will be detailed in Chapter 2. Helping professionals must be prepared to help individuals, families, and communities with emerging problems that affect their lives (figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10. As a human services worker it is very important to stay abreast of the constant change of new information and changes while honoring the past community and family practices that have worked well for those involved.

When working with clients and evidence-based practices, you should stay abreast of new research. Stay aware that most communities of color did not document or research their practices in the way that the White and European cultures have. Approaches that have been passed down and been effective in these communities are also valid. This effort to be informed is part of your ongoing education as a professional and allows you to collaborate with others and understand your clients’ personal values and preferences.

1.4.7 Trauma-Informed Care and Trauma-Specific Practices

Trauma-informed care (or trauma-informed approach) assumes that an individual is more likely than not to have some history of trauma. This systems-based approach can be used by an entire school, agency, or governmental service to define a culture that is sensitive to all of the individuals who work and are served by the organization. Various models of trauma-informed care emphasize the following principles:

- understanding of trauma and stress;

- safety and security;

- cultural humility and responsiveness;

- compassion, dependability, and trustworthiness;

- collaboration and empowerment, and choice;

- resilience and recovery.

Trauma-informed care has been practiced for centuries, although not always formally acknowledged, amongst Indigenous and Black communities. Indigenous healing movements have focused on restoring family and social relations for centuries. Acknowledging the historical violence against Indigenous, Black, and other people of color is a critical part of diagnosing trauma (Wright et al., 2021).

There is an important distinction to be made between trauma- informed care and specific trauma services that are medical in nature.Trauma-specific practices are focused medical and psychological interventions, typically practiced by a licensed provider. Examples include treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and addiction recovery.

These approaches are such an important foundation of this profession that an entire chapter of this text is devoted to trauma experiences and trauma responses. See Chapter 9 for more on this topic.

1.4.8 Strengths-Based Approach

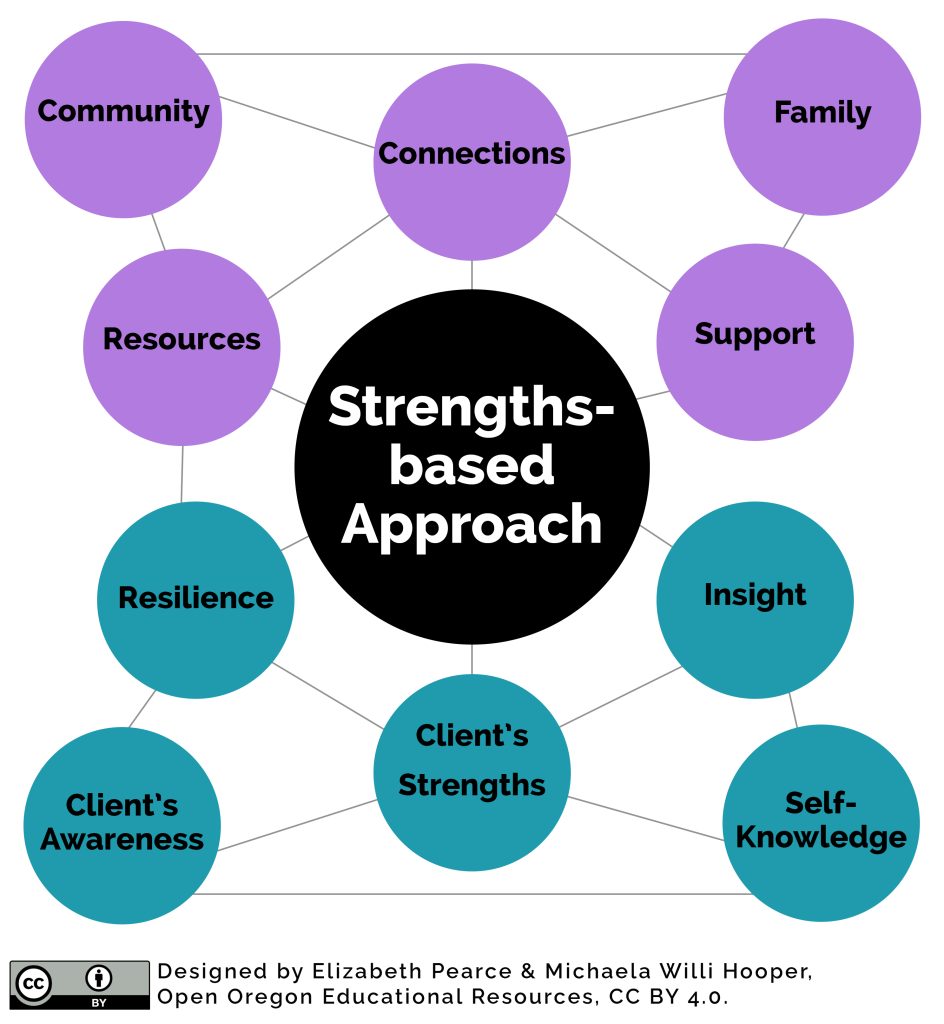

The strengths-based approach, also known as the strengths perspective, emphasizes that every person, group, family, and community has strengths; and every community or environment is full of resources (Johnson & Yanca, 2010). Often attributed to Bertha Reynolds, a mid-twentieth century social worker, and Dennis Saleeby a late twentieth century scholar, the approach actually has foundation in the work of Black scholars and social workers. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote about the strength of Blacks to adapt and survive in hostile conditions. In the early twentieth century, Black social workers such as Birdye Henrietta Haynes, Elizabeth Ross Haynes, and others focused less on pathologizing Black people and more on the strengths and resilience strategies within families and communities (Wright et al., 2021).

Like trauma-informed care, a strengths-based approach emphasizes the resources, resilience and strengths within the individual and their community. Professionals help the client identify their strengths. Sometimes society and individuals are focused on the negative impacts of their lives and have a difficult time identifying the positive aspects of their lives and situations. At the same time, be careful not to tell others that they need to be positive all the time. Being strengths-based is different from toxic positivity, which involves dismissing negative emotions and responding to distress with false reassurances. When using the strengths approach not only is the human services professional or social worker helping the client to identify their personal strengths, but the worker is also helping the client identify local resources to help the client needs. There are many things to keep in mind, as figure 1.11 illustrates.

Figure 1.11. A strengths-based approach emphasizes the resources, resilience and strengths within the individual and their community.

Figure 1.11 Image Description

This approach focuses on the strengths and resources that the client already has rather than building new strengths and resources. There is an emphasis on the client seeing and acknowledging their own assets and value. The reasoning behind the strengths approach is to help clients find solutions to immediate problems, and to identify and build strengths to use in the future.

1.4.9 Cultural Responsiveness

Cultural responsiveness, also known as a culturally responsive approach, involves being aware that each individual you meet has their own set of beliefs, values, routines, and rituals that contribute to their culture. While we may know enough to respond to external cues, such as language and ways of dress, it is important to realize that the client may have internal cultural values not visible right away. Culture comes not only from race, ethnicity,or religion, but includes other influences such as workplace cultures, geographically based culture, sexuality based culture.It can take some time to understand enough of a person’s cultural background to support their efforts to solve life’s problems.

Cultural responsiveness includes the acknowledgement of the effects of dominant culture on those who are members of marginalized groups. For example, the feminist approach to human services and social work is based on the belief that it is not the female psyche that is a problem but that societal patriarchal structures are oppressive to women (Enge, 2013). Another example is the LGBTQ+ approach which also emphasizes affirming the identities and experiences of the LGBTQ+ individual (Four Basic Guidelines for Practicing LGBTQ-Affirming Social Work, n.d.).

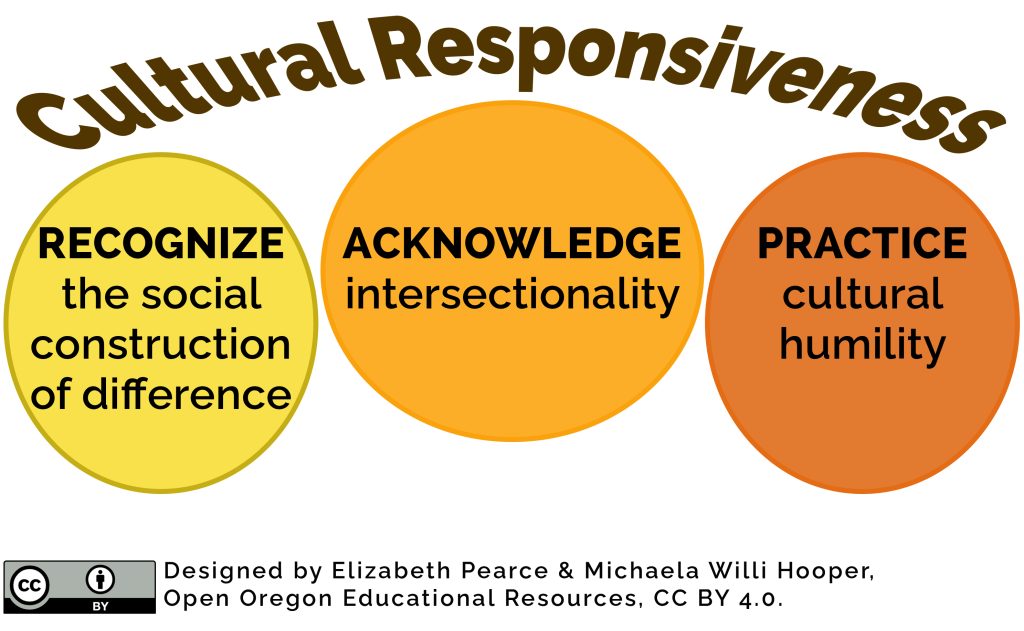

Cultural responsiveness means being aware of cultural factors and responding to them in an appropriate manner as described in figure 1.12. As a human services professional, learning about cultures is a part of your job. You can learn about culture specifically from that culture’s members, but do not expect people from marginalized groups to do all the work of teaching you. Read, listen, and watch media sources created by (not for) members of a culture. Culturally responsive human services workers include culture as part of their assessments. They tailor their interventions to take the client’s culture and the effects of oppressive systems into account.

Figure 1.12. Cultural responsiveness includes understanding the social construction of difference, which is described below, intersectionality, and attending to what others tell us about their experiences, cultural humility.

People are the experts on their own lives. To be truly client- centered professionals must keep in mind what a person’s values are, and what their preferences are for the outcome of their life situation. It can be tempting to think that as a professional one knows what is best but each individual, and their values, traditions, and culture must be respected.

1.4.10 Social Constructivism

Social constructivism, or using a constructivist approach, relates to a general theory from the field of sociology. This approach is based on the understanding that knowledge is constructed through our interactions with others. Community members agree upon shared definitions and meanings.

Social constructions also relate to all aspects of society. For example, what kinds of food would you expect to see on the menu when you go out for breakfast in the United States? What if the venue were described as a Mexican restaurant? Or as a Chinese restaurant? And what if you traveled to another country, say, Korea? What is eaten for breakfast varies from culture to culture and even person to person. And yet, in general, the socially constructed idea of what is typically breakfast food in the United States: eggs, bacon, sausage, cereal, toast, yogurt, and fruit, but not vegetables, noodles, pinto beans, ice cream, or hot dogs (figure 1.13).

Figure 1.13. A variety of foods that are considered breakfast, depending on location and time.

One way that you can recognize that something is a socially constructed idea is that it differs from place to place and changes over time. In other words, what is most common for breakfast varies by location. In addition, whatever is part of the socially constructed idea (in this case what typical breakfast foods are) becomes the norm or what is expected. While we might welcome trying some different foods for breakfast, they are not what is seen as the typical, or expected, American breakfast foods.

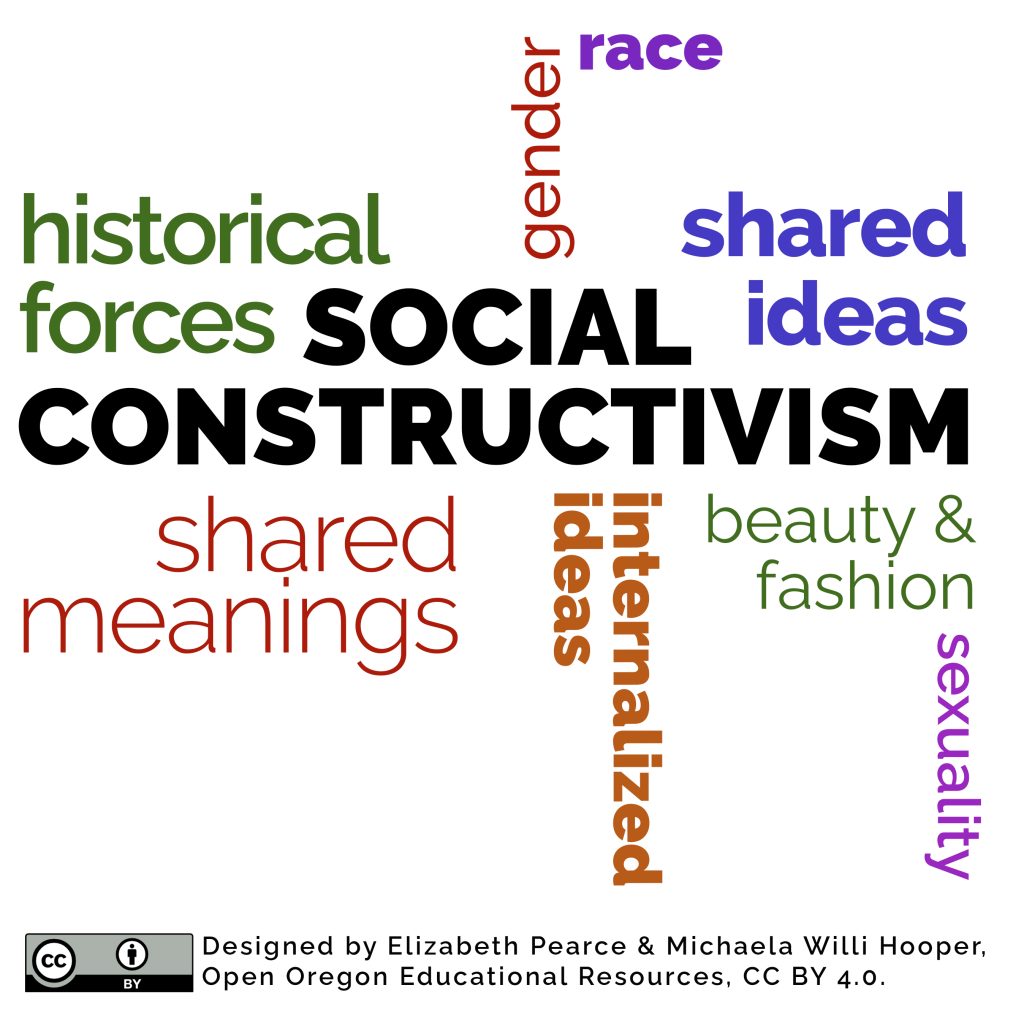

What do social constructions have to do with families and human services professionals? When looking forward to serving individuals and families, we must continually remind ourselves that the idea of the family, and in particular the internalized belief that there is a normal family, is actually a social construction as described in figure 1.14.

What is considered a regular or normal family in the United States? Generally, the traditional (or “regular”) American family has been represented by institutions such as the media and the government as the nuclear family with a male and female heterosexual married couple who is middle class, White, and with several children. When society or the individuals within a society designate one kind of family form to be traditional or the norm, this implies a value, or a preference, for this kind of family structure with these particular social characteristics.

Figure 1.14. Social constructivism includes shared meanings and internalized ideas that are often not part of our conscious thinking. We may accept these ideas as “natural” or “real” but they are actually created via stereotypical thinking and then taught via social interactions.

As a professional in human services, we must constantly self-correct these powerful images that, despite our best efforts, may be instilled inside us. We may not realize that we have internalized these preferences. Specifically, it is important to separate family form (the structure of any family) from family function (how the family operates within itself and in society.) Human services professionals are concerned with the latter, helping people to solve their problems and to function effectively. Families can function healthfully in any form. Human services professionals can use the lens of social constructivism to reinforce the validity of all family forms.

1.4.11 Where Theory and Practice Meet

All of these approaches may be used in a variety of settings. It can be helpful to think about where you might apply these perspectives in your daily life. Human services is often described as being applied at the macro, mezzo, or micro levels (figure 1.10).

Figure 1.15. The human services profession is broad and allows practitioners to move among the micro, mezzo, and macro levels.

1.4.11.1 Micro Level

Micro-level practice happens directly with an individual client or family; in most cases this is considered to be case management and therapy service. Micro-level work involves meeting with individuals, families or small groups to help identify, and manage emotional, social, financial, or mental challenges, such as helping individuals to find appropriate housing, health care, and social services. Micro-level practice may even include helping military officials and families cope with military life and circumstances, helping with school related resources, or working with clients around substance use, homelessness, or food insecurity.

The focus of micro-level practice is to help individuals, families, and small groups by giving one on one support and providing skills to help manage challenges (Johnson & Yanca. 2010). Many professionals begin at the micro level to understand the inequalities, disadvantages, systemic oppression, and the needed advocacy for vulnerable populations.

1.4.11.2 Mezzo (Meso) Level

Mezzo (meso) level practice involves developing and implementing plans with communities such as neighborhoods, places of worship, and schools. Professionals interact directly with people and agencies that share the same passion, interest, location, or challenge. The big difference between micro- and mezzo-level social work is that instead of engaging in individual counseling and support, mezzo practitioners help groups of people. Human Service professionals might help establish a free food pantry within a local place of worship, health clinics to provide services for the uninsured, or community budgeting/financial programs for low-income families.While working at the mezzo level, professionals should be aware of the system oppression that affects individuals, families, and communities. For example, a community that has high levels of contamination in its air and water, it may not be enough to advocate for additional health care resources. It may be equally valuable to advocate for the source of pollution to be clearly identified, and pressured to make changes.

1.4.11.3 Macro Level

Macro-level practice is similar to mezzo practice in that both tend to address social problems. But the macro practice is on a larger and less direct scale and often with a preventative approach. The responsibilities on a macro level typically are finding the root cause, the why, and the effects of citywide, state, and/or national social problems. Awareness of systems of privilege and oppression are foundational to this work.

Professionals are responsible for creation and implementation of human service programs to address large scale social problems. Macro-level social workers often advocate to encourage state and federal governments to change policies to better serve vulnerable populations (Kirst-Ashman & Hull, 2015). They may be employed at nonprofit organizations, public defense law firms, government departments, and human rights organizations. While macro-level human services or social workers typically do not provide therapy or other assistance (case management) to clients, they may interact directly with the individuals while conducting interviews if they are doing research that pertains to the populations and social inequalities of their interest.

The human services and social work professions are broad and allow practitioners to move within the micro, mezzo, and macro levels. As you continue to read this text, consider the approaches described above as well as the level of human services work that is most appealing to you.

1.4.12 References

Dziegielewski, S. (2013). The changing face of health care social work (3rd ed.). New York: Springer.

Elements Behavioral Health. (2012, August 10). What are evidence- based practices? https://www.promises.com/addiction-blog/evidence-based-practices/

Enge, Jacqueline. (2013). Social Workers’ Feminist Perspectives: Implications for Practice. Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/174

Flamand, L. (2017). Systems theory of social work. People of everyday life. http://peopleof.oureverydaylife.com/ systems-theory-social-work-6260.html

Four basic guidelines for practicing LGGTQ-affirming social work. (2019, November 4.). USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. https://dworakpeck.usc.edu/news/four-basic-guidelines-for-practicing-lgbtq-affirming-social-work

Inderbitzen, S. (2014, February 3). What does it mean to be a social work generalist? Social work degree guide. https://www.socialworkdegreeguide.com/what-does-it-mean-to-be-a-social-work-generalist/

Johnson, L. C., & Yanca, S. J. (2010). Social work practice: A generalist approach (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Kirst-Ashman, K. K., & Hull, G. H., Jr. (2015). Generalist practice with organizations and communities (6th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Lewin, R. G. (2009). Helen Harris Perlman. In Jewish women: A comprehensive historical encyclopedia. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/perlman-helen-harris

Pardeck, J. T. (1988). An ecological approach for social work practice. The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 15(2), 134-144. http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol15/iss2/11

Steyaert, J. (2013, April). Ann Hartman. In History of social work. https://www.historyofsocialwork.org

Wright, K. C., Carr, K. A., & Akkin, B. A. (2021). Whitewashing of Social Work History. Advances in Social Work, 21(2/3), 274–297. https://doi.org/10.18060/23946

1.4.13 Licenses and Attributions for Theories and Practices Central to Human Services

1.4.13.1 Open Content, Original

“Theories and Practices Central to Human Services” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where noted otherwise.

“Theories and Research” by Terese Jones is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.7. Table of Types of Research Bias by Terese Jones is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.8. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems.Visualization by Elizabeth B. Pearce/ Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.9. “Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Approach” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.10. “Evidence-Based Practice” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.11. “Strengths-Based Approach” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.12. “Cultural Responsiveness” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.14. “Social Constructivism” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.15. Micro, Mezzo, Macro Visualization by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

1.4.13.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

“A Generalist Approach” and “Systems Theory” by Aikia Fricke and Ferris State University Department of Social Work, Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Vignette and Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Approach by Susan Tyler in Human Behavior and the Social Environment I is licensed CC BY NC SA.

“Social Constructivism” is adapted from “The Family: A Socially Constructed Idea” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 2e, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: edited for clarity; contextualized for human services professions; updated images.

Figure 1.6. Photo of Aikia Fricke is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.13. My very first breakfast in Tabriz by Mohammadali F. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; “Breakfast Burrito” by JBrazito. License: CC BY-NC 2.0; “breakfast in Warsaw” by marktristan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Image Description for Figure 1.11:

The words Strengths-Based Approach are in a large bubble centered in the middle. Ten smaller bubbles are around it, some connected to one another by a line.The following bubbles are violet, and more related to external resources:

- Connections, connected to Community, Resources, Support, and Family

- Community, connected to Connections and Resources

- Resources, connected to Community and Resilience

- Support, connected to Family and Connections

- Family, connected to Support and Connections

The following bubbles are teal, and more connected to internal resources:

- Resilience, connected to Client’s Awareness, Resources, and Client’s Strengths

- Client’s Awareness, connected to Resilience and Client’s Strengths

- Client’s Strengths, connected to Insight, Self-Knowledge, Resilience, and Client’s Awareness

- Insight, connected to Self-Knowledge and Client’s Strengths

- Self-Knowledge, connected to Client’s Strengths and Insights