4.5 Defining Poverty

As with any problem, in order to discuss the different ways to approach poverty, we first have to define what the problem is. With poverty, that can be complicated, as there are multiple ways to think about the word itself. While a basic definition of poverty would be the state of lacking material and social resources needed to live a healthy life, we will examine a couple of approaches to defining poverty.

4.5.1 The Relative Approach

The relative approach to defining poverty considers a person poor when their income is much lower than the typical income in that population. The “relationship to the median income could be called relative poverty” (Mangum, Mangum, and Sum, 2003, p. 9). This means that if we find what the income is for the most average family—in other words, a family that has more income than 49.999% of the population and less income than 49.999% of the population—we could decide, for example, that anyone whose family made one third (⅓) that income level or less was officially poor. This means that the poverty line for that population would shift as the median income shifts (in other words: constantly).

There are good and bad points to the relative approach to defining poverty. First of all, we’re comparing people to others around them to get an idea of how badly they are doing in comparison to others (hence the term relative approach). That means that different income levels could apply in different states, or even different counties or towns within the same state. These people represent those most in need in their various communities.

From a social justice perspective, this approach would help us to focus upon moving toward equality. The more people are poor under a relative definition, the more we know inequality is a problem. The closer we get to a fair distribution of income and resources, the fewer people there would be below the poverty line using this approach.

4.5.2 The Absolute Approach

The American government defines poverty using the absolute approach. To put it simply, the absolute approach designates a basic subsistence income level (the absolute version of a poverty line) and anyone who falls below that line is considered poor. This is the approach that most of us know better, as it is a fairly straightforward thought: a family is poor if their income is below (x) dollars. This basic approach does not require a lot of explanation on the surface.

However, what remains unclear with that definition (and often goes unasked) is just exactly how that subsistence level of income is calculated. A 1955 survey by the Department of Agriculture determined that Americans spent about a third of their total income on food. This didn’t tell anyone how much of their income poor families spent on food, just that the typical American family budget was one third for food, two thirds for everything else. Taking that approach, the government identified the most frugal diet among the many options that the Department of Agriculture had recently recommended as potential bases for family food budgets and multiplied it by three. Essentially, they took the minimum cost of feeding an average family and used that to determine how much money a family should need to get by as long as they were also being as frugal as possible in every other area of their budget (figure 4.5) to create the poverty line. Then, as now, the poverty line varied based upon the size of one’s family, since the amount of food necessary to feed a family increased with the size of the family (Katz, 1996; Mangum, Mangum, & Sum, 2003).

Figure 4.5. Although groceries have gone up in price, other expenses, such as housing, have gone up more dramatically.

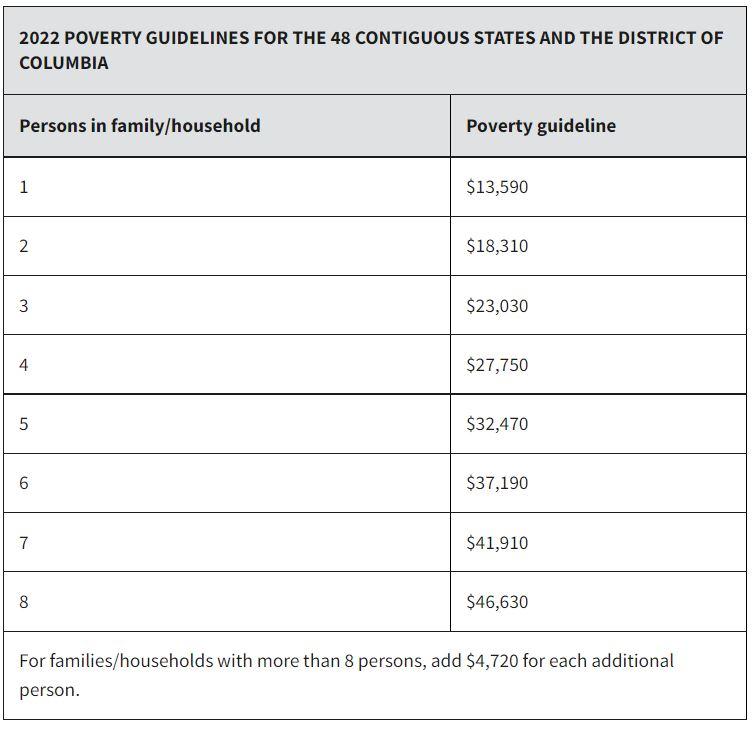

The government still uses an outdated calculation method invented in the 1950s to determine the poverty line, based on a family’s food budget being one third of their total budget. The cost of living in the 1950s isn’t comparable with today, as there are additional expenses that didn’t exist at the time or were used less frequently, such as internet access, cell phones, and child care. Other costs have risen more sharply than the cost of food, rendering the multiplier of three obsolete. Additionally, establishing a national poverty line seems impractical when one considers the divergent costs of living in different places. The poverty line is adjusted each year related to food prices, as shown in figure 4.6, but does not adjust for inflation in other goods and services.

Figure 4.6. While the majority of states share the same guidelines, the guidelines for Hawaii and Alaska are separate, and slightly higher (e.g. starting at 15,630 for Hawaii and at 16,990 for Alaska with a household size of one.) (U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022.)

4.5.3 The Poverty Line and The Poverty Gap

Beyond the issues with varied costs of living, the absolute approach to defining poverty also falls short in determining how a family is actually living. A healthy family of four with two young parents who are nonsmokers and nondrinkers is likely to have very few medical expenses. A different family of four could have two special needs kids and a father with diabetes, incurring much higher medical expenses. That family could have an income well above the poverty line but be struggling worse than some families below it due to their higher everyday expenses that have nothing to do with subpar budgeting skills.

In the end, there probably isn’t a perfect way to define poverty that addresses all of these issues and still can be calculated easily enough to make the government’s job of determining benefit eligibility less cumbersome. Social scientists tend to favor the relative approach since it gives a snapshot not only of the number of families who need assistance, but also an idea of the overall inequality among the economic classes.

Another measure of that inequality is called the poverty gap, which goes beyond just telling us how many families fall below the poverty line. The poverty gap measures the difference between the poverty line and the actual income level of the average poor family (Mangum et al., 2003). The United States has one of the worst poverty gaps among economically advanced nations, hovering around 18%, while countries like Finland, Czechia, and Denmark are between 5 and 7% and the average is about 11% (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2016).

4.5.4 References

4.5.5 Licenses and Attributions for Defining Poverty