9.3 Trauma: A Common Experience

Trauma impacts people of all ages and all walks of life. Over 60% of adults have experienced at least one traumatic event and about 25% reported experiencing three or more traumatic events before the age of 18 (Merrick et al., 2018). Working in the human services profession, you are likely to encounter many clients who have been traumatized. As a result, it’s crucial to understand what trauma is and how you may directly or indirectly address it in your career. At the same time, you are likely to hear many stories of trauma when working with clients, which can be a traumatic experience in and of itself. This is another reason that it is essential for human service workers to understand trauma and have knowledge of wellness practices to address it.

9.3.1 Defining Trauma

Over the past few decades, a number of different definitions of trauma have been developed by professionals and researchers. Desiring a unified concept, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) drew on these existing definitions to establish a framework for understanding trauma.

According to SAMHSA (2014), trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. Generally, there are four kinds of trauma: acute trauma, chronic trauma, complex trauma, and intergenerational trauma.

- Acute trauma is a single traumatic incident. An example would be a car accident or even a natural disaster. It may only be a single incident, but it can have lasting effects such as fear of being in a vehicle.

- Chronic trauma is a traumatic experience that is repeated over a period of time. This type of trauma would include domestic violence and war. Both have lasting effects on many people and the consequences can be hard to overcome.

- Complex trauma is a repeated traumatic experience inflicted by a caregiver. This includes, but is not limited to, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and verbal/emotional abuse (also known as psychological abuse). Complex trauma leaves a child confused and conflicted. The person who inflicted harm was supposed to be the one protecting them and keeping them safe. When that does not happen the child is then in a predicament where they do not know who to trust.

- Intergenerational trauma, as defined by the American Psychological Association, is “a phenomenon in which the descendants of a person who has experienced a terrifying event show adverse emotional and behavioral reactions to the event that are similar to those of the person himself or herself,” (American Psychological Association [APA], 2022). Many groups have experienced intergenerational trauma, including descendants of holocaust survivors, Rwandan genocide survivors, Native American boarding school survivors, and enslaved persons. Parents and grandparents pass down trauma responses in the way they model and teach relationship skills, behaviors, values, and beliefs.

While trauma is sometimes considered an emotional response, recent evidence shows that traumatic experiences can have physiological impacts. The study of how your behaviors and environment can cause changes is called epigenetics. Unlike genetic changes, epigenetic changes are reversible and do not change your DNA sequence, but they can change how your body reads a DNA sequence ((What Is Epigenetics?, 2022)). A 2016 study found evidence of epigenetic changes transmitted across generations to descendants of Holocaust survivors, providing the first human evidence that intergenerational trauma may also have a biological mechanism (Yehuda et al., 2015).

Regardless of the means of transmission–social, biological, or both–intergenerational trauma can threaten a family’s sense of safety and create problems within families. This kind of trauma may impact the bonds that grandparents, parents, and children can form, often making these relationships difficult and emotionally stunted. At the same time, more significant issues that can emerge from this, such as suicidality, substance use disorders, and difficulty regulating aggression, can lead to adverse outcomes like additional trauma and family instability. Still, the research on intergenerational trauma continues, and there is still much for us to learn about how it functions.

9.3.2 Three Es of Trauma

SAMHSA also developed the concept of the three Es of trauma: event(s), experience of event(s), and effect. These three Es further define the concept of trauma and its effects on individuals.

9.3.2.1 Events

Events or circumstances include the actual fear of reaching out for help, the extreme threat of physical or psychological harm (i.e. natural disasters, violence, etc.), or severe neglect for a child that imperils a healthy range of factors, including the individual’s cultural development (SAMHSA, 2014). These events may occur once or may be repeated over time.

9.3.2.2 Experiences

The individual’s experience of these events helps to determine whether it is a traumatic event (SAMHSA, 2014). Something traumatic for one individual may not be traumatic for another individual. For example, two soldiers may serve in a combat zone, but only one may develop post-traumatic stress disorder. Similarly, siblings may respond differently to the incarceration of a parent.

How an individual experiences the event may be linked to various factors. These factors include the individual’s cultural beliefs, such as the subjugation of women and the experience of domestic violence). Another factor is the availability of social support, whether isolated or embedded in a supportive family or community structure. Finally, they also include the developmental stage of the individual. For instance, an individual may understand and experience events differently at age five, fifteen, or fifty (SAMHSA, 2014).

9.3.2.3 Effects

The long-lasting adverse effects of the event are a critical component of trauma. These adverse effects may occur immediately or may have a delayed onset. Examples of adverse effects include an individual’s inability:

- To cope with everyday stresses

- To trust and benefit from relationships

- To manage cognitive processes such as memory and attention

- To regulate behavior

- Or to control the expression of emotions.

In addition to these more visible effects, there may be an altering of one’s neurobiological make-up and ongoing health and well-being (SAMHSA, 2014).

Traumatic effects may range from hypervigilance or a constant state of arousal to numbing or avoidance. These effects can eventually wear a person down, physically, mentally, and emotionally. Trauma survivors have also highlighted the impact of these events on spiritual beliefs and the capacity to make meaning of these experiences (SAMHSA, 2014). In the next section, we’ll discuss the science behind how trauma impacts physiological and psychological processes.

9.3.3 The Science of Trauma

Recent research and the development of new theories have helped us better understand how trauma affects individuals in the long term. These theories give us an idea about how early trauma disrupts neurodevelopment and psychological processes. At the same time, by better understanding trauma, we can work to develop better interventions to address its impact.

9.3.3.1 Attachment Theory

Children who experience trauma may develop issues with attachment. Attachment theory, pioneered by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, highlights how attachment patterns originate from the earliest stages of life. Bowlby’s work focused on the bond between the infant and the primary caregiver. He developed a model of four stages of early development attachment that children go through from birth to two years old. He believed this was a critical part of development and that attachment experiences have long-lasting impacts on children. Particularly that these early attachment experiences shape future relationship patterns.

Ainsworth expanded upon this work to develop a typology of four kinds of attachments that children have with their mothers. In her research, she looked at how children between the ages of one and two responded to mothers leaving and returning. Her research describes the following attachment types:

- secure attachment: children are distressed when their mothers leave and quickly become calm when their mothers return.

- anxious-avoidant attachment: children do not seem to care when their mothers leave, despite internal distress, and do not react when their mothers return.

- anxious ambivalent attachment: children are in distress when their mothers leave and feel ambivalent when their mother returns, alternating between being clingy and avoidant.

- disoriented-disorganized attachment: children lack any consistent pattern in response to separation and return of the mother.

Like Bowlby, she claimed that these attachment styles impacted future relationships outside of the family. Because of this, the development of a secure attachment is integral to children’s emotional, cognitive, and interpersonal development. There is some research to support these claims. Research suggests that children are more likely to develop secure attachments if parents consistently meet their needs (Lahousen et al., 2019).

So how do these ideas about attachment relate to trauma? Early traumatic experiences can influence the extent to which children feel safe and can form secure attachments. Traumatic experiences are associated with insecure attachment styles and have a neurobiological impact on individuals, particularly during the early stages of development (Lahousen et al., 2019). Trauma impacts various brain regions, some of which encode traumatic information that may later lead to emotional or behavioral problems (Lahousen et al., 2019). These regions are involved in development, leading to behavioral problems and stress reactions later on (Lahousen et al., 2019). These issues often reflect an insecure attachment style.

9.3.3.2 Adverse Childhood Experiences

The second area of research and theory that has advanced our understanding of trauma is the research on adverse childhood experiences. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are traumas that occur in an individual’s life before they turn 18, which include neglect, abuse, and household difficulties. The greater the number of ACEs an individual has experienced, the greater the likelihood of poor social, emotional, and health outcomes in the short and long term.Specifically, researchers have identified ten adverse childhood experiences:

- emotional abuse

- physical abuse

- sexual abuse

- witnessing violence against mother/stepmother

- substance abuse in household

- mental illness in household

- parental separation or divorce

- incarcerated household member

- emotional neglect

- physical neglect (About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study, 2021)

Hudson Center for Health Equity and Quality has developed an online calculator for adverse childhood experiences where you can calculate your ACE score. This online tool is based on the CDC-Kaiser Adverse Childhood Experiences Study but is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Adverse childhood experiences impact children in the short and long term. In the short term, children may internalize or externalize their emotions related to the trauma that they have experienced. Children may respond to these experiences by externalizing their emotions, a psychological defense mechanism in which they direct uncomfortable feelings at others or “act out.” They may engage in inappropriate or disruptive behavior or become diagnosed with ADHD or conduct disorders. In contrast, children may respond to these issues by internalizing their emotions, a similar defense mechanism that involves holding in or hiding their feelings. Children who internalize may experience anxiety and/or depression. In both cases, children’s neurodevelopment is disrupted, which leads to a greater likelihood of long-term impacts from these experiences (McLaughlin et al., 2014).

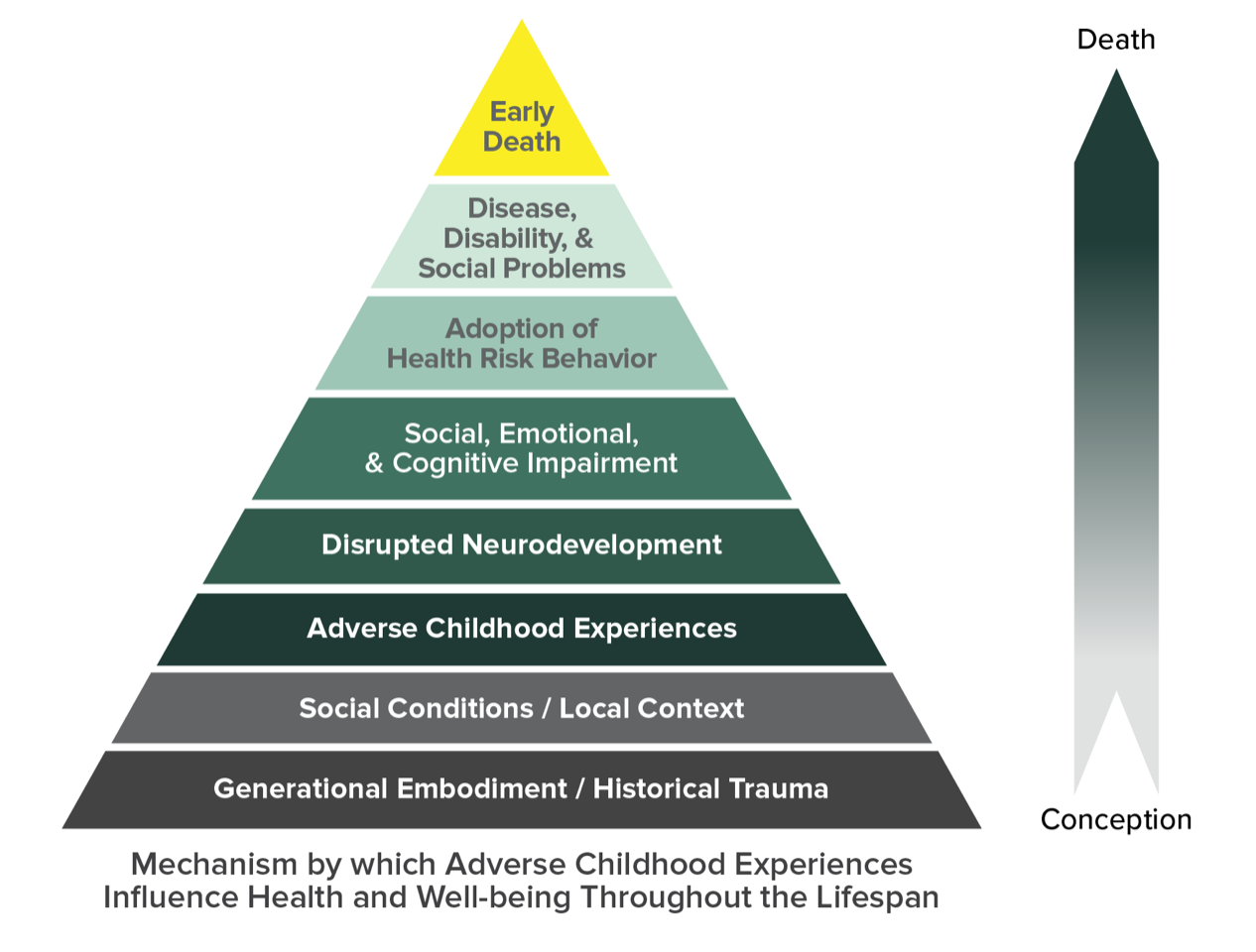

ACEs can impact health across the lifetime. Figure 10.1 shows the pathway from adverse childhood experiences to poor health outcomes and well-being over the life course.

Figure 9.1. The ACE Pyramid shows how adverse childhood experiences influence long-term health outcomes.

Adverse childhood experiences arise from a combination of social conditions and individual interactions. For instance, when we look at the bottom of the ACE pyramid in figure 9.1, we can see how issues such as historical trauma or other social/community conditions can lead to adverse childhood experiences.

In the following sections, we’ll look at different kinds of trauma commonly experienced by children and adults that you may encounter while working in the human services profession.

9.3.4 Child Abuse

Child abuse is the intentional emotional, negligent, physical, or sexual mistreatment of a child by an adult (Bell, 2013). Child abuse is common. At least 1 in 7 children have experienced child abuse and/or neglect in the past year (Fast Facts: Preventing Child Abuse & Neglect, 2022). One of the many reasons these statistics are so concerning is that child abuse is trauma.

Abuse comes in many forms, including physical, emotional/verbal, and sexual abuse. According to the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN, 2021), physical abuse is defined as any act, completed or attempted, that physically hurts or injures a child. NCTSN also describes that acts of physical abuse include hitting, kicking, scratching, pulling hair, and more. Child Protection Services typically get reports of bruises and other noticeable marks when investigating a report of physical abuse.

Emotional abuse is nonphysical maltreatment of a child through verbal language. NSPCC (National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children) states that emotional abuse includes humiliation, threatening, ignoring, manipulating, and more. (National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, 2017) Abusers can combine emotional abuse with other forms, like physical and sexual abuse. Most reports of emotional abuse are harder to prove; thus, physical or sexual abuse tends to be the main cause of removal from a home.

Sexual abuse is maltreatment, violation, and exploitation where a perpetrator forces, coerces, or threatens a child into sexual contact for sexual gratification and/or financial benefit. Sexual abuse includes molestation, statutory rape, prostitution, pornography, exposure, incest, or other sexually exploitative activities.

(American Society for the Positive Care of Children, 2017). Sexual abuse is also a common adverse childhood experience. About 1 in 4 girls and 1 in 13 boys experience child sexual abuse at some point in childhood (Fast Facts: Preventing Child Sexual Abuse, 2022). Like other forms of child abuse, sexual abuse is overwhelmingly perpetrated by someone close to the child. Data show that 91% of child sexual abuse is perpetrated by someone the child or child’s family knows (Fast Facts: Preventing Child Sexual Abuse, 2022).

Abuse does not always have to be physical, sexual, or verbal assault. It can also be neglect. According to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), neglect is the failure to meet a child’s basic needs.

Children most at risk for abuse and neglect are younger children and children with substantial disabilities dependent on their caregivers (Risk and Protective Factors, 2022). In both cases, they may not yet have the cognitive abilities or power to report what is occurring.

Biological parents most often perpetrate abuse and neglect. Caregivers who have the greatest risk of engaging in child abuse or neglect are those who:

- have drug or alcohol issues

- have mental health issues, including depression

- were abused or neglected as children

- are young, are single parents, or have many children

- have a low level of education

- experience high levels of parenting or economic stress

- use spanking and other forms of corporal punishment for discipline

- have attitudes accepting of or justifying violence or aggression (Risk and Protective Factors, 2022)

Despite child abuse and neglect being common experiences, not all cases come to the attention of child protective services. There are a variety of reasons for this. Children sometimes didn’t realize what was happening was wrong or illegal. In the cases where a child is aware, they often have concerns about what would happen if they did report what was happening (National Research Council et al., 2014). In the cases where adults may be aware, there are also reasons that they may choose not to report. These include personal attitudes about what may happen if they report the abuse, the relationship of the adult to the caregiver engaging in abuse, lack of certainty about maltreatment, and lack of an understanding of child abuse reporting laws (National Research Council et al., 2014). These disparities are referred to as the hidden figure of child abuse. Still, even if child protective services identify children experiencing abuse, these experiences can also be traumatic and expose children to more trauma – especially if the state places them into foster care.

9.3.5 Intimate Partner Violence

The United States recognizes intimate partner violence as a significant public health issue. This type of violence is universally condemned due to its heinous nature. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as any incident or pattern of behaviors (physical, psychological, sexual, or verbal) used by one partner to maintain power and control over the relationship. IPV also includes violence between intimate partners (heterosexual, cohabitating, married, same-sex, or dating) (McGarry, Ali, & Hinchliff, 2016; Stark & Filtcraft, 1998).

Historically, in the United States, IPV has been considered an act of violence committed by men toward women. While heterosexual women commonly experience IPV, it can occur to people of any gender and sexuality as shown in figure 9.2. Young women are particularly at risk as IPV declines with age. Perpetrators of IPV are most often heterosexual men. Engaging in IPV has been linked with being unemployed, low income, involved with aggressive peers, and having conduct problems or anti-social behavior (Capaldi et al., 2012).

Figure 9.2 Intimate partner violence is extremely common, especially for women

There are three kinds of IPV:

- Physical violence consists of touching or painful physical contact, including intimidation of the victim through pushing, slapping, hair pulling, arm twisting, disfiguration, bruising, burning, beating, punching, and use of weapons.

- Sexual violence consists of making degrading comments, touching in unpleasant means of harm, addressing a partner in a degrading way during sexual intercourse, and marital rape.

- Psychological and emotional violence consists of threatening, intimidating, killing of pets, deprivation of fundamental needs (food, clothing, shelter, sleep), and distorting reality through control and manipulation.

Many abusers may use a combination of these tactics to establish power and control over the person they are abusing, frequently using physical and sexual violence to reinforce the subtle methods of physical and emotional abuse. Figure 9.3 looks at the wheel of power and control. This tool was developed to help survivors make sense of their experience of abuse.

9.3.6 Wheel of Power and Control

Figure 9.3 Understanding the Power and Control Wheel [Youtube Video].

The Power and Control Wheel discussed in figure 9.3 shows how forms of abuse work together to maintain control over the victim. Practitioners developed this through focus groups with women who had experienced abuse. Since then, it has been widely shared as a tool to help practitioners, community members, and abuse survivors understand how abuse functions.

9.3.6.1 Questions to Consider

- Why is it difficult for people in abusive relationships to leave the person abusing them?

- How can the wheel of power and control help us better understand the behavior of abusers?

Feminist perspectives on intimate partner violence have provided fruitful explanations for why it is so common in our society. Within the feminist perspective, intimate partner violence results from the patriarchal system. In this system, men perpetrate violence against women. They exploit power differentials that keep women oppressed to maintain control over every aspect of their lives. Society socializes males into male entitlement and violence used to sustain abuse (McPhail et al., 2007).

More contemporary feminist perspectives have also acknowledged that there are male victims and women perpetrators of abuse and that abuse also occurs in same-sex couples. Explanations for this kind of violence highlight how members of oppressed groups may internalize violent attitudes and behaviors from the dominant culture. This abuse may also be a response to oppressive social structures through violent means (McPhail et al., 2007). Even so, feminist theory points out that heterosexual women are more likely to be abuse victims than other groups (McPhail et al., 2007).

Feminists also see intimate partner violence as a public concern rather than a private matter. Because this issue continues due to social, cultural, and political forces, feminists want to see changes in policy related to intimate partner violence. These changes include establishing organizations to serve victims of intimate partner violence, treating men who perpetrate this violence, and increasing accountability in the criminal justice system (McPhail et al., 2007).

Still, contemporary feminist perspectives argue that victims should have a choice and voice in crafting solutions to these problems (McPhail et al., 2007). Not every person who experiences intimate partner violence has the same desires for how they would like to see the situation resolved. Some may want to press charges in court, while others may want their partner to receive services and try to reconcile. Others may want perpetrators to be held accountable but want to use practices outside the traditional court process, such as restorative justice, which we discuss in Chapter 12

Intersectionality is also an important part of the feminist perspective. Intersectionality recognizes that individuals are impacted differently based on social class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability, and age. Intersectionality highlights how it is important to look at not just one person’s identity if you want to understand their experiences but all of their identities and how they intersect. Feminist theorists also apply this lens to intimate partner violence, connecting this issue to broader issues of racism, classism, and poverty (McPhail et al., 2007).

Intersectional feminist perspectives point out that low-income and/or undocumented women may struggle to leave their abusers because they are financially dependent on them (Boggess & Groblewski, 2011). Many low-income women experiencing abuse report feeling that lack of economic support is a larger problem after leaving than the treatment they endured, prioritizing basic needs for themselves and their children over counseling services (Boggess & Groblewski, 2011). Black and Latino women may face cultural pressures to stay in their marriage from their families, friends, or religious institutions (Boggess & Groblewski, 2011). Marginalized women also report feeling that some providers lacked cultural sensitivity and understanding (Boggess & Groblewski, 2011). A truly feminist perspective considers all of these factors and prioritizes the wants and needs of the individual woman who is affected.

9.3.7 Sexual Violence

Sexual violence includes harassment, assault, and rape. It is a common misperception that women are at greater risk of sexual violence from strangers. In reality, women are most likely to experience sexual violence from men they are intimate with or know. More han 1 in 3 women and 1 in 4 men have experienced sexual violence involving physical contact during their lifetimes. Nearly 1 in 5 women and 1 in 38 men have experienced completed or attempted rape, and 1 in 14 men was made to penetrate someone (completed or attempted) during htheirlifetime.Men are overwhelmingly the perpetrators of sexual violence. Still, similar to intimate partner violence, sexual violence can affect individuals of any gender or sexuality.

College students are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence compared to non-students. Male college-aged students (18-24) are 78% more likely than non-students of the same age to be victims of rape or sexual assault (Fast Facts: Preventing Sexual Violence, 2022). Female college-aged students (18-24) are 20% less likely than non-students of the same age to be victims of rape or sexual assault (Fast Facts: Preventing Sexual Violence, 2022).

There are several reasons that sexual violence is rampant, especially on residential four-year campuses. On many campuses, students lack knowledge of reporting sexual violence when it occurs. When it does get reported, colleges and universities rarely punish perpetrators of sexual violence and remove them from campus. College students engage in unsupervised heavy alcohol consumption, especially in greek life and high-powered athletic programs. This party culture creates an environment where predators have more opportunities to assault people sexually. Finally, there is a lack of education about consent.

One of the significant issues in the United States is that our society has failed to adequately address sexual violence and support victims. In fact, out of every 1000 instances of rape, only 13 cases get referred to a prosecutor, and only 7 cases will lead to a felony conviction (Rape Abuse and Incest National Network [RAINN], n.d.). Instead of a culture where institutions hold perpetrators of sexual violence accountable, American society is one where rape culture is common. Rape culture refers to a society or environment where there is a culture of disbelief and lack of support for sexual violence survivors through normalizing and trivializing sexual violence despite its prevalent occurrence.

There are many examples of rape culture in institutions. Rape culture is when administrators ask, ‘what were you wearing?’ or ‘how much did you have to drink?’ as a student is trying to report a rape that occurred at a fraternity party to a campus administrator.

Rape culture is also present in the criminal justice system. The case against the rapist Brock Turner highlighted thowrape culture can manifest. Brock Turner brutally raped an unconscious college student behind a dumpster and was caught in the act by two men. During the trial, Brock’s father declared that Brock should not have his life ruined over “20 minutes of action.” Ultimately, the California judge gave Brock only three years of probation. This example captures how rape culture exists in individual attitudes and how institutions function. Despite the egregious and substantiated nature, Brock faced few consequences for his actions, and the court system did not treat this as a serious offense. More broadly, this case reflects the dismal statistics on prosecution and convictions of rape in the US.

9.3.8 References

About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study. (2021, April 6). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

American Society for the Positive Care of Children (ASPCC). (2017). Child sexual abuse. Retrieved from http://americanspcc.org/child-sexual-abuse/

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.). American Psychological Association. https://dictionary.apa.org/intergenerational-trauma

Bell, K. (2020, June 24). Child Abuse. Open Education Sociology Dictionary. https://sociologydictionary.org/child-abuse/

Boggess, J., & Groblewski, J. (2011, October). Safety and Services: Women of color speak about their communities. Center for Family Policy and Practice. https://safehousingpartnerships.org/sites/default/files/2017-01/Safety_and_Services.pdf

Capaldi, D. M., Knoble, N. B., Shortt, J. W., & Kim, H. K. (2012). A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231–280. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3384540/

Fast Facts: Preventing Child Abuse & Neglect. (2022, April 6). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html#:%7E:text=Child%20abuse%20and%20neglect%20are%20common

Fast Facts: Preventing Child Sexual Abuse. (2022, April 6). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childsexualabuse/fastfact.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Fchildabuseandneglect%2Fchildsexualabuse.html

Fast Facts: Preventing Sexual Violence. (2022). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/fastfact.html

Lahousen, T., Unterrainer, H. F., & Kapfhammer, H. P. (2019). Psychobiology of Attachment and Trauma—Some General Remarks From a Clinical Perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 914. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6920243/

McGarry, J., Ali, P., & Hinchliff, S. (2017). Older women, intimate partner violence and mental health: A consideration of the particular issues for health and healthcare practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(15-16), 2177-2191. doi:// 10.1111/jocn.13490

McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2014). Childhood Adversity and Neural Development: Deprivation and Threat as Distinct Dimensions of Early Experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 578–591. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4308474/

McPhail, B. A., Busch, N. B., Kulkarni, S., & Rice, G. (2007). An Integrative Feminist Model: The Evolving Feminist Perspective on Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Against Women, 13(8), 817–841. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207302039

Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences From the 2011–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 States. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537

National Research Council, Institute of Medicine, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Committee on Law and Justice, & Committee on Child Maltreatment Research, Policy, and Practice for the Next Decade: Phase II. (2014). New Directions in Child Abuse and Neglect Research (A. C. Petersen, J. Joseph, & M. Feit, Eds.). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK195982/

Risk and Protective Factors. (2022, April 6). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/riskprotectivefactors.html

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). (n.d). Families and trauma. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/families-and-trauma

National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. (2017). Emotional abuse: What is emotional abuse? Retrieved from https://www.nspcc.org.uk/preventing-abuse/child-abuse-and-neglect/emotional-abuse/what-is-emotional-abuse/

SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (No. 14–4884). (2014). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Stark, E., & Filtcraft, A. (1998). Women at risk: Domestic violence and women’s health. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 8(3), 232-234.

What is Epigenetics? | CDC. (2022, May 18). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/epigenetics.htm

What to Expect from the Criminal Justice System. (n.d.). RAINN. https://www.rainn.org/articles/what-expect-criminal-justice-system

Winninghoff, A. (2020). Trauma by Numbers: Warnings Against the Use of ACE Scores in Trauma-Informed Schools. Occasional Paper Series, 2020(43), 32–43. https://educate.bankstreet.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1343&context=occasional-paper-series

Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Bierer, L. M., Bader, H. N., Klengel, T., Holsboer, F., & Binder, E. B. (2015). Holocaust Exposure Induced Intergenerational Effects on FKBP5 Methylation. Biological Psychiatry, 80(5), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.005

9.3.9 Licenses and Attributions for Trauma: A Common Experience

“Trauma: A Common Experience” by Alexandra Olsen is a remix of “Chapter 7:Child Welfare and Foster Care” by Eden Airbets in Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University, “Chapter 9: Social Work and the Healthcare System” by Kaitlin Ann Hetzel in Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University, “Chapter 9 Safety and Stability” by Alexandra Olsen in Contemporary Families:An Equity Lens 2nd edition, “Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence” by the CDC, and “Chapter 4: Violence Against Women” by Bureau of International Information Programs, United States Department of State in Global Women’s Issues: Women in the World Today, extended version licensed under CC BY 4.0. Substantial modifications and edits have been made.

Figure 9.1 is from “About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study”, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

Figure 9.2 is from “Fast Facts Preventing Intimate Partner Violence”, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All other content in this section is original content by Alexandra Olsen and licensed under CC BY 4.0.