9.5 Trauma-Informed Care

Now that we’ve addressed how human service professionals address specific traumas in their work, we’ll look more broadly at practices that any organization or agency can implement.

In treatment settings, there is a helpful distinction between treating the trauma experience and treating the symptoms of trauma (Atkins, 2014; Dass-Brailsford, 2007; Friedman et al., 2014). Although there are numerous evidence-based treatment approaches for treating the experience of trauma, not all providers are trained and qualified to treat trauma. Trauma treatment requires specialized training and supervised experience (Dartmouth, 2015; SAMHSA, 2014a). This has the potential to create a treatment gap between the number of trained providers in trauma care and the treatment needs of patients with trauma histories. Even though not every provider is trained to engage in trauma processing therapies, it is recommended that institutions train their professional staff in the ability to provide care that is sensitive to the unique symptoms of trauma (SAMHSA, 2014b). A structured approach that institutions can use for providing such care is known as trauma-informed care (SAMHSA, 2014a; Curran, 2013).

Trauma-informed care is a collection of approaches that translate the science of the neurological and cognitive understanding of how the brain processes trauma into informed clinical practice for providing services that address the symptoms of trauma (SAMHSA, 2014a; Curran, 2013). It is important to note that trauma-informed care is distinct from trauma-specific practices.

Trauma-specific practices directly treat the trauma an individual has experienced and any co-occurring disorders that they developed due to this trauma. Trauma-specific practices include interventions such as prolonged exposure therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (Menschner & Maul, 2016). Practitioners must undergo special trainings to utilize these techniques, which means that not every organization may offer these treatments.

A trauma-informed care approach can include trauma-specific practices and incorporate key trauma principles into the organizational culture.This approach is not designed for the treatment of the trauma experience (e.g., processing the trauma narrative), but rather for assistance in managing symptoms and reducing the likelihood of re-traumatization of the patient in the care experience (Najavits, 2002; SAMHSA 2014b). As such, interventions of trauma-informed care are appropriate for a range of practitioners to utilize in various clinical settings.

9.5.1 Assumptions of Trauma-Informed Care

Along with defining the concept of trauma, SAMHSA’s approach to trauma-informed care includes four assumptions and six key principles. There are four Rs that highlight the key assumptions of the trauma-informed care framework: realization, recognition, response, and resistance to re-traumatization.

A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed

- realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery

- recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system

- and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization (SAMHSA, 2014b).

9.5.1.1 Realization

By realizing trauma, people’s experiences and behavior are understood in the context of coping strategies designed to survive adversity and overwhelming circumstances. Their experiences and behavior may be related to past circumstances, such as a client dealing with prior child abuse. They may currently be experiencing trauma, such as a client experiencing intimate partner violence. Finally, clients’ experiences and behavior can be related to the emotional distress that results in hearing about the firsthand experiences of another, such as the vicarious trauma experienced by a human service professional.

There is an understanding that trauma plays a role in mental and substance use disorders. Prevention, treatment, and recovery settings should systematically address trauma (SAMHSA, 2014b). Trauma is not only present in the behavioral health sector. Trauma also plays a significant role in areas such as education, child welfare, criminal justice, healthcare, and other community organizations addressing social problems. Trauma is equally a barrier to effective outcomes in these systems as it is in mental health and substance use disorder treatment.

9.5.1.2 Recognition

When engaged in trauma-informed care, people in the organization or system can also recognize the signs of trauma, including how these may appear differently in different settings or populations (SAMHSA, 2014b). People in the organization use screening and assessment tools to help identify trauma. Additionally, organizations should provide training for staff members so that they can identify trauma responses.

9.5.1.3 Response

The program, organization, or system responds by applying the principles of a trauma-informed approach to all areas of functioning. The program, organization, or system integrates an understanding that the experience of traumatic events impacts all people involved, whether directly or indirectly (SAMHSA, 2014b). Staff in every part of the organization change their language, behaviors, and policies to consider the experiences of trauma among children and adult users of the services and staff providing the services.

Organizations accomplish these changes through staff training, a budget that supports this ongoing training, and leadership that realizes the role of trauma in the lives of their staff and the people they serve. The organization has practitioners trained in evidence-based trauma practices. The organization’s policies, such as mission statements, staff handbooks, and manuals, promote a culture based on beliefs about resilience, recovery, and healing from trauma. The organization is committed to providing a physically and psychologically safe environment. Leadership ensures that staff work in an environment that promotes trust, fairness, and transparency. The program’s, organization’s, or system’s response involves a universal precautions approach in which one expects the presence of trauma in the lives of individuals being served, ensuring not to replicate it (SAMHSA, 2014b).

9.5.1.4 Resistance to re-traumatization

A trauma-informed approach seeks to resist the re-traumatization of clients and staff (SAMHSA, 2014b). In a trauma-informed environment, staff recognize practices that strip clients of agency or make them feel trapped – both of which they may find re-traumatizing. At the same time, trauma-informed organizations ensure they are not re-traumatizing staff by creating a high-stress environment without proper support.

9.5.2 Key Principles of Trauma-Informed Care

In addition to these four assumptions, there are six key principles of a trauma-informed approach: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues.

- Safety refers to staff and clients throughout the organization feeling secure physically and psychologically. The physical setting and interpersonal interactions at the organization should promote safety. Staff at the organization should not assume what their clients need to feel safe but rather provide opportunities for clients to express what that means to them.

- Trustworthiness and transparency are directly related to one another. When organizational decisions are made with transparency, they build and maintain a sense of trust with clients, staff, and others involved with the organization.

- Peer support is another principle that helps build trust, enhance collaboration, and establish safety and hope. By having support from others who have experienced trauma, survivors can begin to see the possibilities of recovery and healing.

- Collaboration and mutuality refer to narrowing power differentials between clients and staff and among staff. Collaboration helps demonstrate that healing happens within relationships and in the meaningful sharing of power and decision-making. By having all parties at the table when decisions are being made, the organization recognizes that everyone has a role to play in creating a trauma-informed organization.

- Empowerment, voice, and choice refer to recognizing and building upon individuals’ skills and strengths. Trauma-informed care is a strengths-based approach, where the organization and its staff foster a sense of resiliency among the people they serve. They believe in the ability of people and communities to heal from trauma and recognize how they are experts in their own experiences. Staff understand how important it is for clients to be empowered and to have a voice and choice in their treatment. Clients are supported in shared decision-making, choice, and goal setting to determine the plan of action they need to heal and move forward (SAMHSA, 2014b). Staff are also empowered to do their work.

- Cultural, historical, and gender issues are the final principle of trauma-informed care. Trauma-informed organizations are aware of cultural biases, stereotypes, and systemic inequalities. In their work, they recognize the role of historical trauma and the importance of addressing that as part of the healing process. In conjunction with this, they have policies, procedures, and culturally responsive protocols, drawing on the unique needs of the population they serve and leveraging cultural connections to improve care.

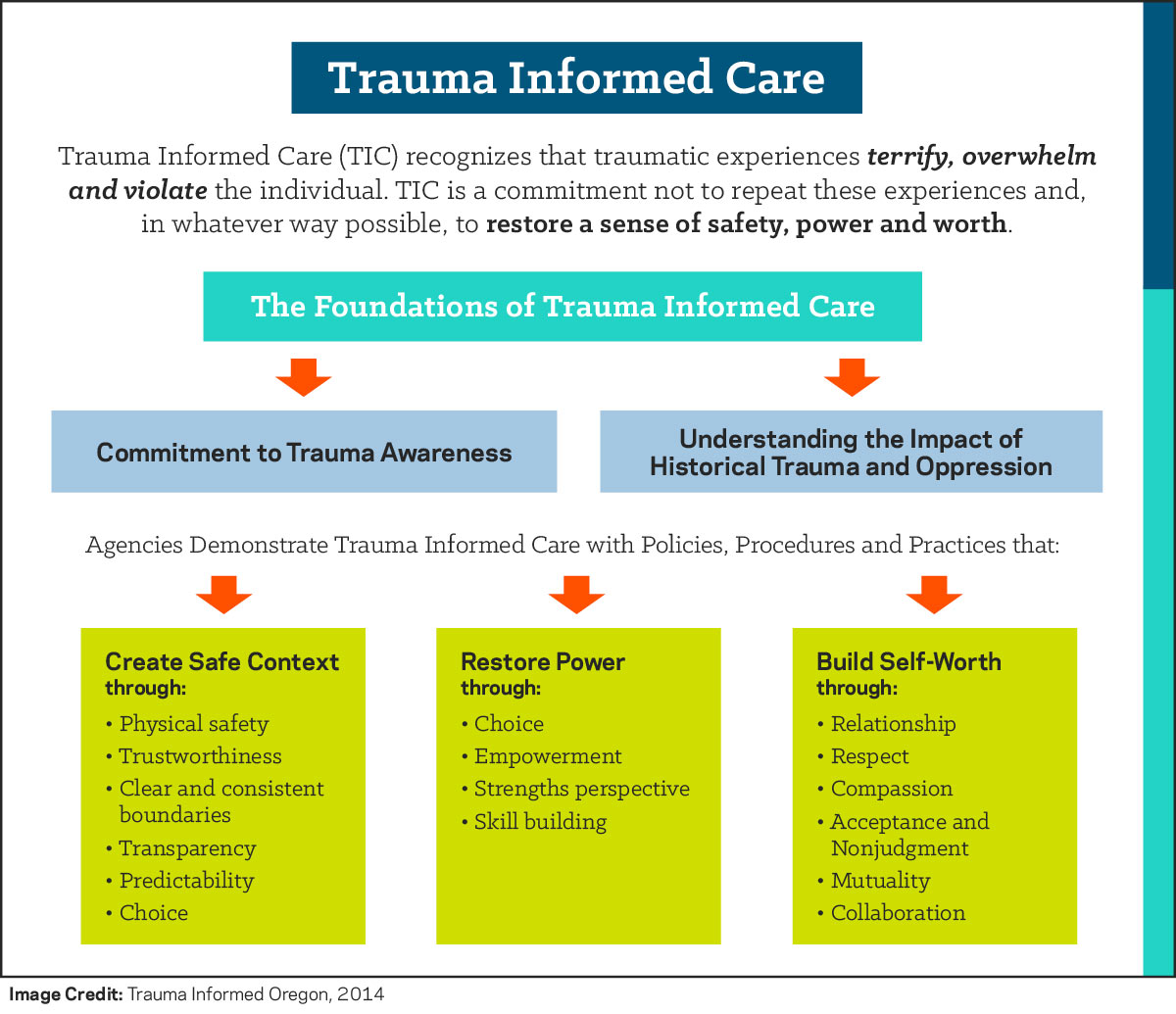

These principles can be applied in many contexts, even though specific practices or terminology vary between settings. Developing a trauma-informed approach requires change at multiple levels of an organization to reflect these principles. Figure 9.4 combines all of the pieces of the trauma-informed care approach we’ve discussed.

Figure 9.4. Concept map summarizing the framework of trauma-informed care

9.5.3 References

Anderson, J. R. (2014). Cognitive Psychology and Its Implications (Eighth ed.). Worth Publishers.

Atkins, C. (2014). Co-Occurring Disorders: Integrated Assessment and Treatment of Substance Use and Mental Disorders (First ed.). PESI Publishing & Media.

Bunting, L., Montgomery, L., Mooney, S., MacDonald, M., Coulter, S., Hayes, D., & Davidson, G. (2019). Trauma Informed Child Welfare Systems—A Rapid Evidence Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2365. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6651663/

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2020). The Importance of a Trauma-Informed Child Welfare System. Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/trauma_informed.pdf

Curran, L. (2013). 101 Trauma-Informed Interventions: Activities, Exercises and Assignments to Move the Client and Therapy Forward (1st ed.). Premier Publishing & Media.

Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center. (2015). Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment: Best Practices, Skills, and Resources for Successful Client Care (Revised ed.). Hazelden.

Dass-Brailsford, P. (2007). A Practical Approach to Trauma: Empowering Interventions (First ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Essential Elements. (2018a). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/trauma-informed-systems/schools/essential-elements

Essential Elements. (2018b). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/trauma-informed-systems/child-welfare/essential-elements

Friedman, M. J., Keane, T. M., & Resick, P. A. (2015). Handbook of PTSD, Second Edition: Science and Practice (Second ed.). The Guilford Press.

LeDoux, J. (2003). Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. Penguin Books.

Menschner, C., & Maul, A. (2016). Key Ingredients for Successful Trauma-Informed Care Implementation. Center for Health Care Strategies. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/childrens_mental_health/atc-whitepaper-040616.pdf

Najavits, L. M. (2002). Seeking Safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance abuse. The Guilford Press.

National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health. (2011). Creating Trauma-Informed Services: Tipsheet Series. http://nationalcenterdvtraumamh.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Tipsheet_Emotional-Safety_NCDVTMH_Aug2011.pdf

SAMHSA. (2014a). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4801. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/

SAMHSA. (2014b). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Turney, K., & Wildeman, C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences among children placed in and adopted from foster care: Evidence from a nationally representative survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 64, 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.12.009

van der Kolk, B. (2015). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Publishing Group.

9.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Trauma-Informed Care

“Trauma-Informed Care” by Alexandra Olsen is adapted from/a remix of “Dynamics of Interpersonal Relations I -Trauma Informed Care” by Jennifer A. Burns, licensed under CC BY SA 4.0. Citations have been edited for style.

Figure 9.4 is adapted from “Dynamics of Interpersonal Relations I -Trauma Informed Care” by Jennifer A. Burns, licensed under CC BY SA 4.0. Citations have been edited for style.

All other content in this section is original content by Alexandra Olsen and licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.