11.3 Working with People Who Use Substances

Ashley Anstett

Ashley Anstett currently works developing model training focused on helping law enforcement and other first responders provide trauma informed care. She came from Oregon Attorney General’s Sexual Assault Task Force, where she served as the Criminal Justice Coordinator for a little over 3 years. Ashley developed and currently teaches a Human Trafficking Class as an adjunct professor at Portland Community College. Ashley graduated from The Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA with a Liberal Arts Degree with a focus on education, law and public policy. In 2015 Ashley began working with The Sexual Assault Resource Center (SARC), primarily with survivors of domestic human trafficking. While at SARC, she was able to serve as a confidential advocate to youth and young adults ages 12-25 and helped them to navigate systems to access resources. Ashley worked as the legal advocate, connected incarcerated survivors to services before their release, was the minor program coordinator, and facilitated at Multnomah County Sex Buyers Accountability and Diversion Program. Ashley understands substance abuse from both her work and her lived experience. She believes it is important to understand substances and addiction, and how marginalized communities have been impacted by the systems they are told to seek help through.

In order to work with individuals who have used substances or struggled with addiction, it is important to understand the complexity of the issue. Addiction is recognized as a disease in the medical community, but because of the behavioral aspect of the disease it can often be viewed by outsiders as a moral failing. To try and address the problem, we created a failed War on Drugs in the 1970 that waged well into the 2000’s, targeting Black communities and other communities of color. The War on Drugs failed because it failed to address the root causes of the issue. It criminalized and made enemies of those struggling with a disease.

In this section we will review:

- Four Principles of Psychoactive Drugs

- Scope of the Problem

- Four Common Drugs

- Drug Policies

- Philosophies of Treatment

- Systemic strengths and challenges

11.3.1 Four Principles of Drugs

First, let’s discuss some general information about what drugs are and how they affect human beings. There are four specific principles of psychoactive drugs to keep in mind.

- Drugs are neither good nor bad. Drugs are merely substances; their use may have positive or negative effects, may hurt or harm people, but that says nothing about the drug itself. For example, Vicodin (generic name: hydrocodone) is a very effective prescription painkiller that provides relief for many people. However, it is also highly addictive, and Vicodin dependence has been known to precede users progressing to heroin use, something that has been obvious in America’s opioid epidemic (Heady & Haverstick, 2014). Vicodin on its own is the same chemical compound regardless of how it’s being used. The drug itself is neither good nor bad.

- Every drug has multiple effects. We have not gotten good enough at crafting drugs to be able to design them to have one specific effect. Drugs have an impact all over the body, including multiple areas of the brain, so it is to be expected that they would engender multiple effects. There is a reason you hear a laundry list of side effects during every pharmaceutical commercial!

- Both the size and quality of a drug’s effect depend on the amount the individual has taken. At times, a drug simply has a more profound effect as the dosage increases. However, with some drugs, different doses seem to bring about different families of results—a phenomenon known as biphasic effects (Ketcham & Asbury, 2000). For example, one or two drinks may leave someone feeling friendlier and more outgoing, while several more drinks may lead to irritability and anger.

- The effect of any psychoactive drug depends on the individual’s history and expectations. We have the ability to adjust to the effects of a drug over time—that is known as building tolerance. Drugs also have pharmacological effects and nonspecific effects. Have you ever known someone who thought he/she was drinking alcohol and started to act drunk, even though there was no alcohol in the drinks he/she was being given? This illustrates how powerful the brain can be in shaping the impact of a specific drug. If one’s brain is expecting to feel a certain way, there is an increased chance one will feel that way upon taking the substance, regardless of whether or not the substance was intended to have that effect (Ksir et al., 2006.)

11.3.2 Scope of the Problem

The World Drug Report 2019 reported that not only are the adverse health consequences of drug use more severe and widespread than previously believed, the severity of the situation is increasing.

- An estimated 35 million individuals globally experienced drug use disorders requiring treatment services and an estimated 271 million (5.5% of the world’s population) used drugs outside of medical recommendation during 2017.

- Only 1 in 7 persons in need of treatment for a drug use disorder receives it.

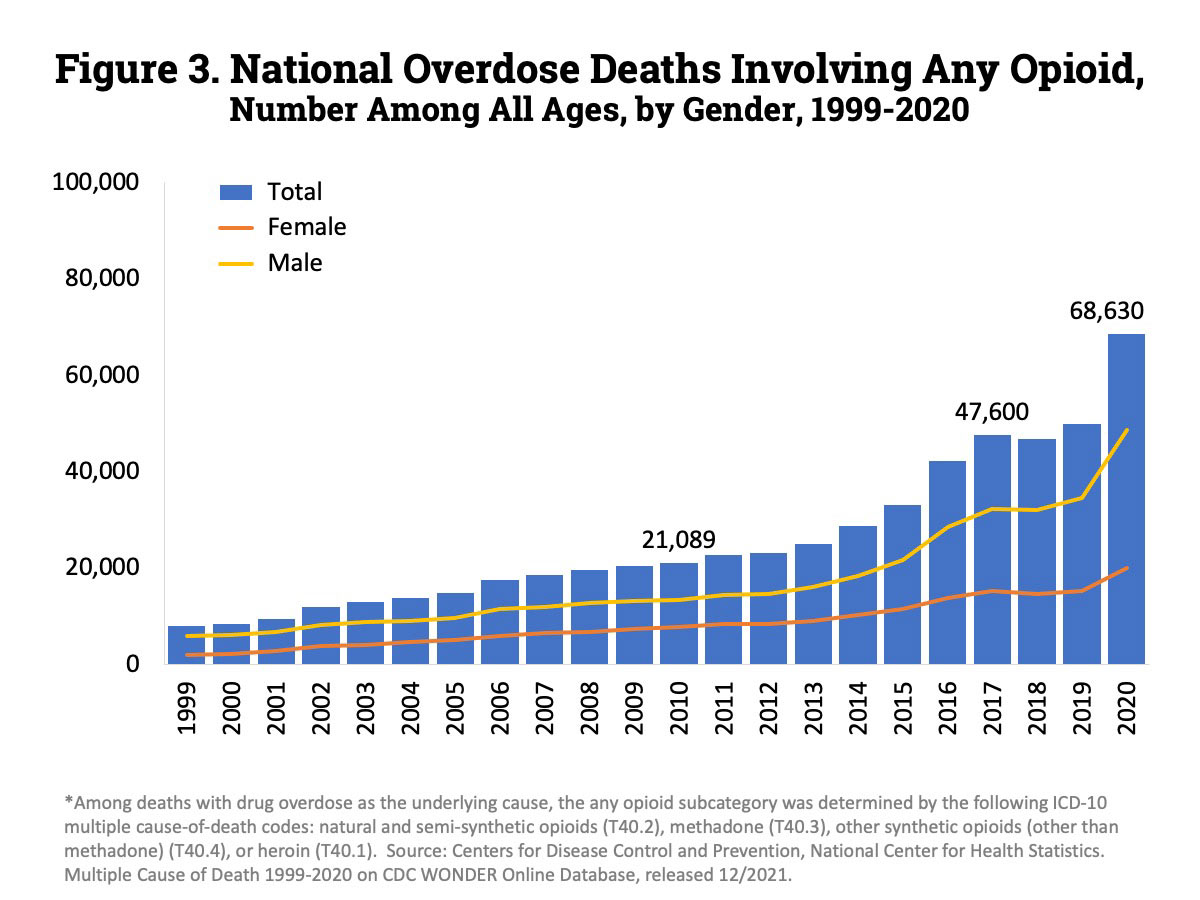

- There were 47,000 opioid overdose deaths reported in the United States during 2017 (up 13% from 2016) and 4,000 in Canada (up 33% from the previous year). An opioid crisis is also arising in West, Central, and North Africa although the specific opioid drugs involved may differ in various parts of the world (WHO, 2019).

11.3.3 Four Kinds of Substances

One way we have found to classify substances in the United States takes into account the impact they have on the central nervous system (CNS) as shown in figure 11.1. In this chapter we will concentrate on four common kinds of drugs: stimulants, depressants, opioids, and cannabis. Stimulants speed up the CNS by increasing heart rate and breathing and raising blood pressure. Stimulants are drugs like cocaine,

Figure 11.1. This is a table that shows the common categories of drugs, classified by how they impact the Central Nervous System. The table is color coded for each category and gives examples of drugs, how the pupils look, and common behavior indicator

methamphetamines, and even caffeine. Depressants depress the CNS and slow down breathing and heart rate. Depressants are substances such as alcohol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines. Opioids and narcotic analgesics work on the opioid receptor in the brain and are used for pain relief. Finally there is cannabis which contains a number of cannabinoids that impact the CNS, most common are THC and CBD.

11.3.3.1 Drug Categories and Their Common Effects

|

Category |

CNS |

CNS |

Hallucinogens |

Dissociative |

Narcotic |

Inhalants |

Cannabis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Common |

Cocaine |

Alcohol |

LSD (acid) |

PCP |

Heroin |

Solvents |

Marijuana Hash |

|

Pupils |

Dilated |

Normal |

Dilated |

Normal |

Constricted |

Normal |

Normal |

|

Common |

Restlessness |

Sluggish |

Hallucinations |

Incomplete verbal response |

Droopy eyes “nodding” out |

Flushed face |

Dry mouth |

Figure 11.1. This is a table that shows the common categories of drugs, classified by how they impact the Central Nervous System. The table is color coded for each category and gives examples of drugs, how the pupils look, and common behavior indicator

11.3.3.2 Cocaine

Cocaine, made from the refined coca plant, is a powerfully addictive stimulant. Cocaine floods the brain with dopamine,and prevents its reabsorption into the brain. The dopamine creates a feeling of euphoria that strongly encourages the drug taking behavior. Cocaine has a long history of use, both medicinally and recreationally, in the United States. Vin Mariani, a popular wine in the 1860’s was said to help suppress the appetite and boost energy levels. Once there became a better understanding of addiction, cocaine was made illegal and eventually criminalized.

Cocaine use has gone in and out of popularity, peeking in the 1970’s and 80’s. Use is dropping amongst young people, as they opt for cheaper, longer lasting alternatives.

Figure 11.2. Vintage poster of Vin Marian, the wine with cocaine, popular in the 1860s.

11.3.3.2.1 Cocaine Use in the United States

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which has collated multiple studies:

- Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 1.9% (or about 5.2 million people) reported using cocaine in the past 12 months.

Source: 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health - In 2021, an estimated 0.2% of 8th graders, 0.6% of 10th graders, and 1.2% of 12th graders reported using cocaine in the past 12 months.

Source: 2021 Monitoring the Future Survey - In 2020, approximately 19,447 people died from an overdose involving cocaine.

Source: CDC WONDER Database (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2021.)

Figure 11.3. This chart shows the number of opioid deaths by gender in the United States. This includes both prescribed opioids and non-prescribed opioids.

People ingest cocaine in a variety of ways including:

- Internasal (snorting)

- Injecting

- Orally (rubbing on gums)

11.3.3.3 Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine is a stimulant that affects the central nervous system, and is similar in chemical makeup as amphetamine, a drug used to treat ADHD. Methamphetamine is made by combining chemicals and other materials to create a chemical “reaction” that produces methamphetamine. Methamphetamine is known by a number of other names like “meth”, “crank”, “ice”, “glass”, “crystal”, and “tina” to name a few. The names reflect its glass like appearance.

Figure 11.4. Methamphetamine, sometimes called “crystal meth” for its appearance, originally was produced for medical purposes such as treating mood disorders or for weight loss.

Methamphetamine was created from a form of amphetamine in Japan around World War II. Post war methamphetamine was used to treat depression and was also prescribed as a weight loss tool. When abuse spiked in the 1960’s the government began to regulate it and use began to decline. It stayed that way until the 1990’s when it exploded back onto the scene. The tools and chemicals used to make methamphetamine were easily available at most grocery stores. Soon regulators caught on and made it harder to purchase Sudifederan, one of the main ingredients in methamphetamine.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which has collated multiple studies:

- Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 0.9% (or about 2.6 million people) reported using methamphetamine in the past 12 months.

Source: 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health - In 2021, an estimated 0.2% of 8th graders, 0.2% of 10th graders, and 0.2% of 12th graders reported using methamphetamine in the past 12 months.

Source: 2021 Monitoring the Future Survey - In 2020, approximately 23,837 people died from an overdose involving psychostimulants with abuse potential other than cocaine (primarily methamphetamine). Source: CDC WONDER Database

People use methamphetamine in these ways:

- Internasal (snorting)

- Injecting

- Orally (rubbing on gums)

11.3.3.4 Alcohol is a Depressant

Alcohol is the most commonly used substance in the United States.

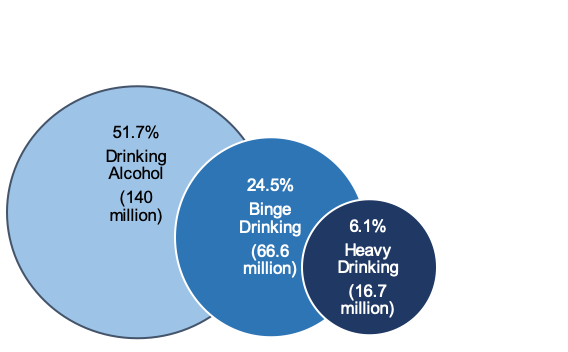

Not all alcohol consumption occurred in risky or problematic amounts, the vast majority of individuals who consume alcohol do so in moderation. This is, however, in contrast to individuals engaging in binge drinking or heavy drinking patterns. The accessibility and normalization of alcohol use can make it challenging for some to recognize if there is an unhealthy relationship to alcohol.

Binge drinking is an unhealthy pattern that some drinkers engage in. One of the environments in which alcohol use is particularly prominent is college. It is not unusual to start drinking before age 21, in fact, the average age at which kids start if they do not wait until 21 is just 14, but many people reach a peak of alcohol use in college (Levinthal, 2014). Binge drinking occurs in over 40% of students during a given two-week period, and 25% of students reported having academic problems they believed to be connected to their drinking.

Figure 11.5. Percent reporting past-month drinking alcohol, binge drinking, and heavy drinking (derived from SAMHSA, 2018 report for persons aged 12+).

Additionally, 20 percent of college students say they have had unplanned and/or unprotected sex while under the influence (Levinthal, 2014). Binge alcohol use in the past month, defined as “five or more drinks (for males) or four or more drinks (for females) on the same occasion (i.e., at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other),” was attributed to 66.6 million individuals (24.5% of population); heavy alcohol use, defined as “binge drinking on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days; all heavy alcohol users are also binge alcohol users”, to 16.7 million (6.1% of population).

Alcohol kills more than five times as many people as all illegal drugs combined (Royce & Scratchley, 1996). Alcohol is synergistic with many other drugs, including barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and painkillers. This means that instead of the effects of the drugs adding up when one takes them together, they multiply each other. It is very dangerous to take these substances together, as the risk of overdose is much higher than it would be for either drug on its own. That is one reason a lot of prescriptions indicate that they should not be taken with alcohol. Another unique aspect of alcohol is that if someone is physically dependent on it, withdrawal can become very dangerous.

The World Health Organization identified alcohol as a significant factor in the global burden of disease (and death)(WHO, 2014). The harmful use of alcohol was defined as: “drinking that causes detrimental health and social consequences for the drinker, the people around the drinker and society at large, as well as the patterns of drinking that are associated with increased risk for adverse health outcomes” (p. 2). Thus, WHO set a goal for a 10% reduction in harmful use of alcohol by the year 2025 around the world because of the many health consequences (and 3 million deaths per year) attributed to this behavior. Reducing and preventing alcohol-related harm is also one of the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare (AASWSW) Grand Challenges for Social Work under the umbrella goal called “Close the Health Gap” (Begun, Clapp, and the Alcohol Misuse Grand Challenge Collective, 2015).

11.3.3.5 Opioids

Opioids affect the neurons in our brain by blocking pain and providing a feeling of calm and euphoria. They serve a very important purpose in the medical field. They have been used for centuries to help alleviate pain and discomfort and improve quality of life. Our body naturally produces opioids as a reaction to pain, so when we flood our system with synthetic opioids over a long period of time, our bodies can become dependent on it. Withdrawal from opioids can feel like a very severe flu and last several days and sometimes even weeks. Often, part of the withdrawal process is the inability to sleep, which can cause depression, anxiety and other mental health problems.

Figure 11.6. Vintage ad for Bayer heroin.

Recently there has been a lot of conversation about opioids and the epidemic we face. However, opioids are nothing new to us here in the United States. Heroin and opium have been around in mainstream culture for more than a century. There were advertisements for Bayer Heroin in the Sears catalog and hypodermic needle kits were sold alongside. As addiction to opium, heroin, and morphine were better understood, more regulations were imposed and medical professionals stopped prescribing it as often.

In 1995, a drug called OxyContin became available. There was a push to prescribe this powerful opioid for both chronic and everyday pain. It was marketed to doctors as safe to prescribe to patients. The lack of oversight on prescribing the powerful drug caused an epidemic of individuals addicted to pain medication. We saw a rise in the use of heroin and opioid related deaths as it became more difficult to obtain OxyContin. According to the National Drug Survey³ heroin use exploded in 2007 and continues to rise. We also saw overdose rates take a drastic upturn in 2010.

Figure 11.7. Heroin use and overdose rate from Center for Disease Control.

11.3.3.5.1 Fentanyl

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that has been available as an effective pain killer for a very long time. It is 100 times stronger than morphine, and because of that has been closely regulated and utilized exclusively by the medical field. As the opioid epidemic grew, the market became flooded with “blues”, which are counterfeit OxyContin cut with fentanyl. Fentanyl has become so widespread, people are accidentally overdosing at very high rates.

11.3.4 Evolution of Drug Policy in the United States

11.3.4.1 Prohibition

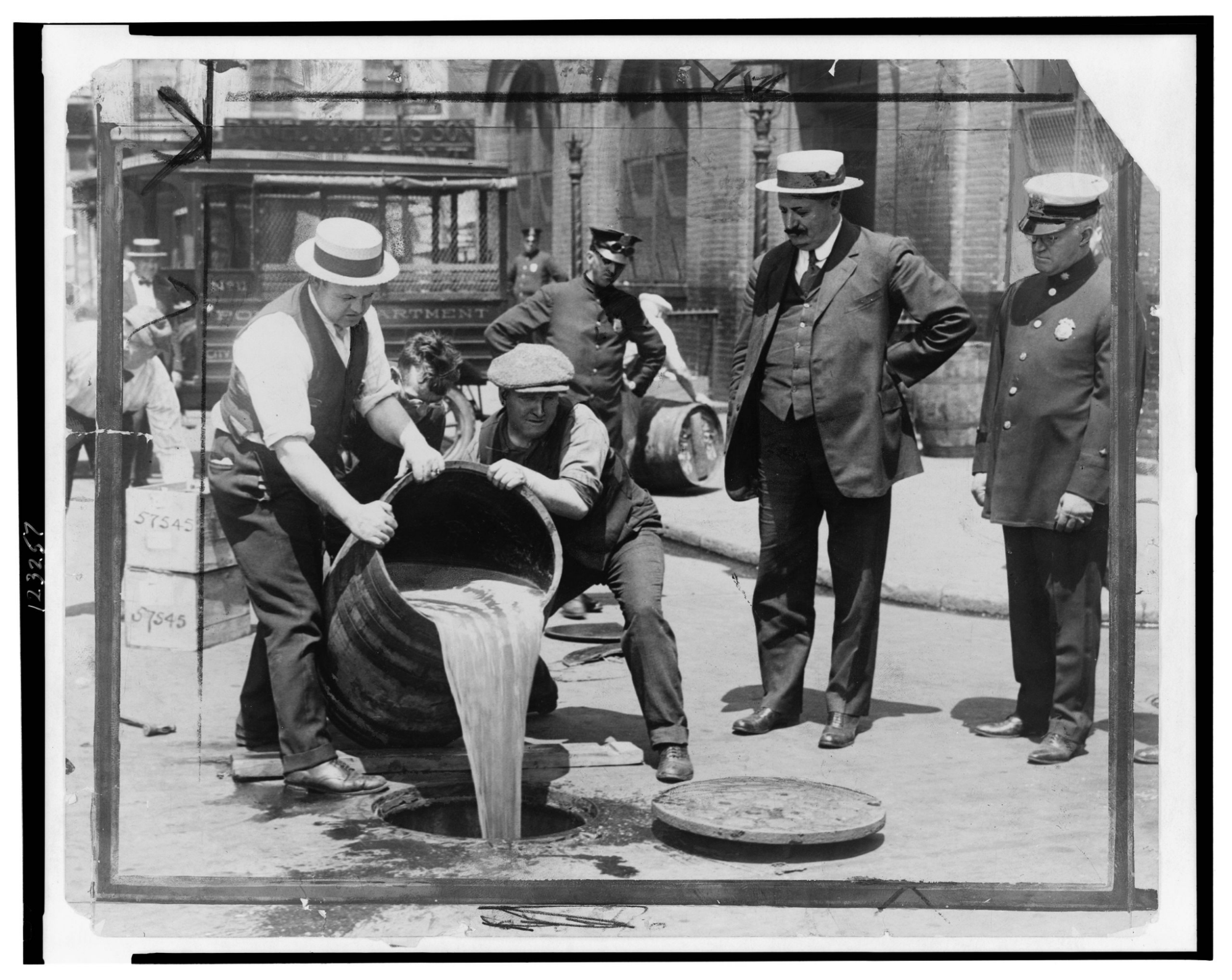

The 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution, commonly known as Prohibition, banned the manufacture, sale, or transportation of “intoxicating liquors,” but not the drinking of alcoholic beverages.

Although the combination of the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution and the Volstead Act (which clarified that beer and wine were included as alcoholic beverages) were implemented beginning in 1920, many states had already enacted their own local prohibition laws (Hanson, Venturelli, & Fleckenstein, 2015; Kelly, 2017).

Figure 11.8. New York City Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach, right, oversees agents pouring liquor into the sewer following a raid after the passage of the federal Volstead Act prohibiting alcohol.

You might find it interesting to pursue historical literature documenting the intersections of alcohol/drug policy with historical and sociological trends such as the temperance movement, women’s suffrage, immigration, organized crime, classism and racism (see for example, Straussner & Attia, 2002; van Wormer & Davis, 2013). Many of these historical policy patterns have implications for today’s politics and policy debates, as does the extensive economic impact of both local and international trade in substances such as alcohol, tobacco, coffee, tea, opium, cocaine, and others. The 21st Amendment repealed the federal alcohol prohibition laws in late 1933; some states and local jurisdictions were slower to change their own prohibition policies. Some states continue to have “dry” communities restricting the sale or distribution of alcohol, and some communities maintain “Sunday” or “blue” laws banning the sale of alcohol during certain hours.

11.3.4.2 War On Drugs

The “War on Drugs” has been called America’s Longest War – and arguably the most unsuccessful. It was started in the early 1960’s in response to the counterculture emerging which centered around the end of the Vietnam war, and sometimes included the use of drugs. The end of the war also brought about soldiers returning home addicted to heroin and other opioids. The government’s solution to the increase in drug use was to criminalize both those that sell drugs and those that use drugs.

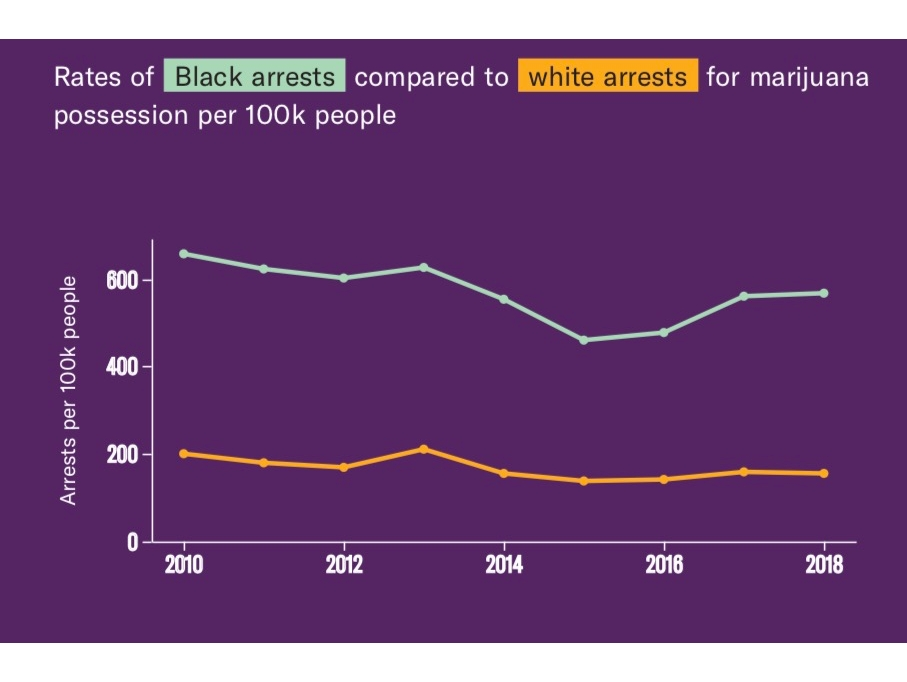

As the War on Drugs waged into the 1980’s, crack soon became the focus. New laws to target dealers made the sentencing laws for crack far outweigh those for powder cocaine. This disproportionately targeted poor, Black and other communities of color. Seventy percent of inmates in the United States are non-White—a figure that surpasses the percentage of non-Whites in US society, which is approximately 23%, according to the 2015 US census. That means that non-White prisoners are far over-represented in the US criminal justice system as shown in figure 11.9.

Figure 11.9. The War on Drugs has criminalized those using and selling drugs, disproportionately targeted Black communities, and failed to reduce drug use or trafficking.

The United States has the highest incarceration rates for drug-related crimes. Michelle Alexander writes extensively of the impact the War on Drugs has had on communities, especially Black communities. Watch the YouTube video below about the War on Drugs that talks about how it impacted the Black community specifically.

Figure 11.10 shows how the War on Drugs impacted Black people and women disproportionately.

The War on Drugs helps explain the relative explosion of women in prison for nonviolent, drug possession charges that occurred during the late 1980s to 1990s—leading to a declaration that the War on Drugs became a “War on Women” (Bloom, Chesney Lind, & Owen, 1994). Women of color have been arrested at rates far higher than White women, even though they use drugs at a rate equal to or lower than White women. Furthermore, according to Bureau of Justice statistics from 2007, nearly two-thirds of US women prisoners had children under 18 years of age.

Before incarceration, disproportionately, these women were the primary caregivers to their children and other family members so the impact on children, families, and communities is substantial when women are imprisoned. Finally, inmates often engage in prison labor for less than minimum wage. When these individuals are incarcerated, corporations contract prison labor that produces millions of dollars in profit. Therefore, the incarceration of millions of people artificially deflates the unemployment rate (something politicians benefit from) and creates a cheap labor force that generates millions of dollars in profit for private corporations.

The War on Drugs is a failure. It is a failure because it addresses none of the core issues that drove it. It treated addicts as criminals and it used the criminal legal system to disenfranchise a generation of people. It did not, and still fails to, address racism, poverty, addiction, unemployment, and other systemic issues that impact marginalized communities.

11.3.4.3 Decriminalization Efforts

Several states have decriminalized the production, distribution, possession, and/or use of cannabis for medical and/or recreational purposes. Some hypothesize that decriminalization of substance possession or use reduces economic incentives for illegal production and distribution of drugs, allowing government entities to increase revenue through taxation (McNeece & DiNitto, 2012). Decriminalization is contested, however, as potentially contributing to increased rates of substance use disorders and other health risks associated with substance use, as well as related problems such as driving under the influence and community safety. Law enforcement professionals expressed grave concerns regarding the potential for increased demands on police forces already stretched by the need to manage alcohol-related situations if marijuana is also legally used by the general public. Recent evidence suggests that the presence of legal (medical) marijuana dispensaries are associated with increased violent and property crime rates in adjacent areas (Freisthler, Ponicki, Gaidus, & Gruenwald, 2016).

Addiction treatment providers have expressed concern about the potential impact of easier access on individuals already in recovery from substance use disorders and the potential for further stressing an under-resourced service delivery system with an increase in demand for intervention to address problems with marijuana use.

11.3.4.4 Marijuana Legalization

During the 1920s and 1930s many states developed prohibition-style policies about marijuana, and the federal government got involved in 1937 with the passage of a Marijuana Tax Act and more severe criminalization policies during the 1950s. Marijuana policy concerns cannabis plant products; the word marijuana came from Mexico, but its use in U.S. policy is becoming recognized as having racist and propagandist connotations by many scholars. Historical roots of marijuana prohibition reveal racial/ethnic bias about Mexican immigrants and African Americans that parallel opium and cocaine policy regarding Chinese immigrants and Southern black workers. Even as more and more states legalize marijuana for recreational use and predominantly white dispensary owners get rich, there are still individuals, most who are People of Color, in prison for having or selling marijuana.

In many of the states that have legalized marijuana they have put some of the revenue made from the sale into addiction treatment, increasing services for vulnerable residents.

11.3.5 Philosophies of Treatment

11.3.5.1 Drug courts

Traditional drug-control methods of the criminal justice system, such as mandatory incarceration and harsher penalties, along with court-mandated treatment following release from incarceration, have not proven to be sufficiently effective to curb the problems associated with illicit drug use (Broadus, 2009). In addition, these efforts also impacted the court system by creating backlogs of cases considered to involve relatively minor, non-violent offenses, and pushing jail populations far over capacity at great public expense. In response, a movement emerged during the early-1990s to establish special courts for managing nonviolent drug-related cases. The mission was to engage individuals in court-monitored, structured, evidence-supported treatment and divert them from being incarcerated if they complied with the treatment plan. By 2018, over half of all U.S. counties sponsored at least one of over 3,100 drug courts in operation (Lloyd & Fendrich, in press). Each program involves an interdisciplinary team of criminal justice and mental health professionals responsible for creating an individualized comprehensive plan for each program participant and monitoring participant progress. Failure to comply with the court-treatment plan results in the court levying the traditional sentences for the original offenses. Short-term outcome studies support the drug court model as participants, on average, remain in treatment longer than in traditional treatment settings and experience fewer relapse events, recidivism rates are lower, and participants are able to improve education, housing, and health, as well. Results generally are not as promising for juvenile drug courts as they are for adult drug courts (Lloyd & Fendrich, in press).

11.3.5.2 Treatment

11.3.5.2.1 Inpatient

Inpatient treatment center, otherwise known as residential treatment, is where the person seeking treatment is required to check themselves into a facility where they can address their substance use issues. Many inpatient programs have limited contact with outside friends and family. Some have what is referred to as a “black out” period, which can be anywhere from the 5 days to two weeks when the individuals first checks in, where they are not allowed to have contact with anyone outside of the facility.

There are a number of specialities that inpatient treatment centers can focus on. Some work with individuals with addiction issues who are coming back into the community from prison or jail, some programs focus on dual diagnosis or trauma, other programs specialize in working with folks from a specific community of culture.

11.3.5.2.2 Outpatient

Outpatient treatment is for individuals who want to address their alcohol and/or drug use but require a lower level of care than those seeking inpatient treatment. Outpatient treatment usually consists of a combination of individual therapy, group therapy, and relapse prevention. There are a number of therapeutic techniques that have been successful in working with individuals with substance use issues.

11.3.5.3 Support Programs

One of the most successful models is the Peer Support model. We know there is nothing like one person helping another person that has a similar experience. In each of the support programs we talk about, one common theme is that there is peer support as a cornerstone of the program.

11.3.5.3.1 Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) are both 12 step programs that are based on the same traditions and practices. They are free support groups that provide a place for alcoholics and addicts to find support and community. AA and NA are world wide organizations that provide free support meetings in most cities in the United States and in many other countries around the world.

Figure 11.11. The 12 Step Meeting Serenity Club in Sturgis, South Dakota, a city of fewer than 7,000 population (as of 2021) in the Black Hills made famous by its array of “biker bars” and its role as host to both the annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally and the activity’s hall of fame.

AA was started in the early 1900’s by Bill W and Dr. Bob. They were the first alcoholics to bring each other together to share stories, provide support and accountability. They believed there was nothing stronger than one alcoholic helping another. AA and NA became a community. In the program, it is suggested that individuals go through each of the 12 steps with a sponsor to help them abstain from drinking and drugs.

11.3.5.3.2 Smart Recovery

SMART stands for Self-Management and Recovery Training. According to their website, this is more than an acronym: it is a transformative method of moving from addictive substances and negative behaviors to a life of positive self-regard and willingness to change. SMART recovery has meetings online and in person.

SMART recovery uses a 4 point program:

- Building and maintaining the motivation to change

- Coping with urges to use

- Managing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in an effective way without addictive behaviors

- Living a balanced, positive, and healthy life

11.3.5.3.3 Rational Recovery

Rational Recovery (RR) was developed by Jack Trimpey in the 1980’s as a solution to his alcoholism. Jack did not believe in many aspects of Alcoholics Anonymous, particularly in the belief of a spiritual aspect to the healing. Some participants go as far as to call it the antithesis of AA. RR focuses on understanding the addict voice inside your head and mastering your thoughts and behaviors. Unlike AA, RR is not free. It is trademarked and available for sale. It has worked for a number of people as an alternative to AA and NA. RR also does not hold meetings, as Timpey did not believe the meetings held any value.

Rational Recovery differs significantly from AA in a number of important ways including:

* Alcoholism is not viewed as a disease

* RR is not a religious/spiritual program

* The label of recovering alcoholic is not used

* There is far less emphasis on recovery groups

* Once AVRT (described below) is mastered there is no need for any additional steps

* Recovery is viewed as an event and not a process

Rational Recovery is similar to AA in that it views lifelong abstinence as the only reliable way to manage this addiction. Figure 11.12 shows many of the affirmations common to recovery programs.

Figure 11.12. Affirmations are a key part of many recovery programs.

11.3.5.3.4 Medically Assisted Treatment (MAT)

Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) uses medication and therapy to treat substance use. MAT is the gold standard of care, which means it is supported by scientific evidence. We know that people who use MAT are more likely to stop using substances and stay in recovery.

These are drugs like Suboxone, Buprenorphine, Methadone, Antabuse, and Campral. Some, like Suboxone and Methadone help to relieve withdrawal symptoms from opioid addiction, where Antabuse prevents someone from drinking by making them sick if they consume alcohol.

11.3.6 Systemic Strengths and Challenges

11.3.6.1 Strengths

The system has not always known what to do with individuals that use substances. It is challenging to support while also ensuring resources are available to those that want them, and are ready to use them.

One place the system has done well is creating wrap around services. That includes services that don’t focus on one area of need, like addiction, but address all the needs at once to give the person a higher rate of success. Wrap around services address both physical and emotional needs. Often they will assign a caseworker (or multiple) that can help with housing, a job, daycare, transportation, etc. and then simultaneously address trauma and other mental health needs.

11.3.6.1.1 Dual Diagnosis

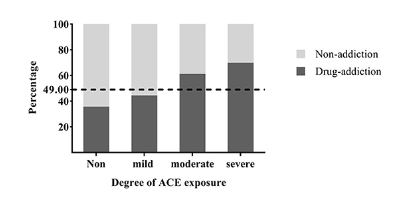

There is an overlap between those that use substances and those that struggle with mental health disorders. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness 1 in 5 US adults struggle with mental illness each year and 1 in 20 struggle with a serious mental illness each year. Those numbers are increasing each year. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 45% of Americans suffer from a dual diagnosis. People diagnosed with mental health disorder have a high risk of having a drug use disorder than the general population as shown in figure 11.13. Based on 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (SAMHSA, 2019a), over 9 million adults aged 18 and older (3.7%) in the U.S. were estimated to have experienced past year co-occurring substance use and mental disorders; for over 3 million (1.3%), their mental disorders were categorized as serious.When treating folks that have a dual diagnosis, it is imperative to work on both the mental health issues and the substance use issues simultaneously. It is also essential that the behavioral treatment and medication be tailored to each individual’s specific combination of mental health and substance use issues.

Figure 11.13. Proportions of drug users with different ACE exposure levels. The dotted line represented the proportion of participants with drug addiction in all.

11.3.6.1.2 Trauma

Acute trauma, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) have a specific correlation with substance use. Many individuals who have experienced trauma report using drugs and alcohol to cope with the symptoms and impact of the traumatic experience. Data from the most recent National Survey of Adolescents and other studies indicate that one in four children and adolescents in the United States experiences at least one potentially traumatic event before the age of 162, and more than 13% of 17-year-olds—one in eight—have experienced posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at some point in their lives. Evidence has shown that the correlation between trauma and substance abuse is particularly strong for adolescents with PTSD. Up to 59% of young people with PTSD subsequently develop substance abuse problems. This seems to be an especially strong relationship in girls. There is a strong correlation between trauma and substance use. Similar to other mental health issues, it is important that we treat both the trauma and the substance use at the same time in order to be most effective.

There has been a push to implement trauma-informed care into systems and services. The very foundation of trauma-informed care is to understand the prevalence of trauma and then acknowledge the systems we have in place have not always provided the most support.

11.3.6.2 Weaknesses

For all the strides we have made in the last few years in understanding addiction and the connection between trauma, mental illness and other core issues, we still have a long way to go.

11.3.6.2.1 Bias

There is a lot of bias, both internal and external, about addicts. Often they are seen as being weak and morally corrupt. The dishonesty and sometimes criminal behavior that drives the disease has an impact on how society views this issue. We know that anyone is vulnerable to addiction, but we more often criminalize vulnerable populations because of it. We see bias in all systems from the medical arena, criminal justice, education, and employment.

Examples of racial disparities in addiction treatment include differences in:

- access to quality treatment

- receiving an accurate diagnosis

- being diverted to addiction treatment rather than the criminal justice system

- rates for completing treatment programs for drug and alcohol abuse

- length of stay in a treatment program

- recovery rates

Each of these things makes a big difference in overall success and recovery rate. In order to provide proper care, we need more culturally competent services and service providers. We need programs to invest in training to understand their bias and how to overcome them.

11.3.7 Summary of Working with People Who Use Substances

11.3.7.1 Want to Know More about Substance Abuse?

- Trends, statistics, and treatment all found at National Institute on Drug Abuse

- Examine the overlap of trauma- informed care with treating substance abuse at this youtube channel: Trauma-Informed Oregon

- Comparing Alcoholics Anonymous with other treatments video

- For a deep dive into understanding the role that millionaire drug dealers have played in this epidemic, listen to this podcast. The Sackler Family:The Most Deadly Drug Dealers in America .

- To understand more about the uneven prosecution of drug use see The Cracks in the System on the ACLU webpage.

11.3.8 References

Begun, Clapp, and the Alcohol Misuse Grand Challenge Collective, 2015

Bloom, Chesney Lind, & Owen, 1994

(Broadus, 2009).

Dept. of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, Overview of findings from the … national survey on drug use and health (2003). Rockville, MD.

Freisthler, Ponicki, Gaidus, & Gruenwald, 2016

Heady & Haverstick, 2014

Ketcham & Asbury, 2000

Ksir et al., 2006

Levinthal, 2014

(Lloyd & Fendrich, in press)

McNeece & DiNitto, 2012

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 2021, June 13. What are the short-term effects of cocaine use?. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/cocaine/what-are-short-term-effects-cocaine-use on 2022, December 6

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 2022, January 26. What is the scope of methamphetamine use in the United States?. Retrieved from https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/methamphetamine/what-scope-methamphetamine-misuse-in-united-states on 2022, December 6

Straussner & Attia, 2002;

van Wormer & Davis, 2013

WHO, 2014

WHO, 2019

11.3.9 Licenses and Attributions for Summary of Substances and Their Impact

“Substances and Their Impact” by Ashley Anstett is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Four Principles of Drugs” by Ashley Anstett is adapted from Drugs and Addiction in Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen. The original and the adaptation are licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: Minor editing for clarity; shortened; refocus of content on to Human Services.

“Scope of the Problem” and “Four Kinds of Substances” are adapted from “Background Facts and Figures” by Patricia Stoddard Dare and Audrey Begun, Introduction to Substance Use Disorders, and “Drugs and Addiction” by Mick Cullen, Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World, both of which are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Adaptations: Remixed content from both sources, edited for brevity and relevance and added images.

“Prohibition,” “War on Drugs,” and “Decriminalization Efforts” are adapted from “A Brief History of Substance Use and Policy Responses in the U.S.” by Patricia Stoddard Dare and Audrey Begun, Introduction to Substance Use Disorders, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Adaptations: Added image, edited for relevance and brevity.

“War on Drugs” is adapted from “Treatment, Jail or Justice?” by Christopher Byers, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 2e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: Copied a small section about women of color.

Figure 11.1. “Drug Categories and Their Common Effects” by Ashley Anstett and Michaela Willi-Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.2. “Vin Mariani” by Jules Chéret is in the public domain.

Figure 11.3. “National Overdose Deaths Involving Any Opioid—Number Among All Ages, by Gender, 1999-2020” is from “Overdose Death Rates” by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) and is in the public domain.

Figure 11.4. “Crystal Meth” by Radspunk is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 11.5. “Percent reporting past-month drinking alcohol, binge drinking, and heavy drinking” by Patricia Stoddard Dare and Audrey Begun is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Data from SAMHSA, 2018 report for persons aged 12+.

Figure 11.6. 1901 Bayer Ad by Bayer Pharmaceuticals is in the public domain.

Figure 11.7. “Today’s Heroin Epidemic Infographics” by the CDC is in the public domain.

Figure 11.8. “[New York City Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach, right, watching agents pour liquor into sewer following a raid during the height of prohibition]” by New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, is in the public domain.

Figure 11.9. “The War on Drugs: Crash Course Black American History #42” by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 11.10. “Rates of Black Arrests Compared to White Arrests for Marijuana Possession Per 100K People” in “Tale of Two Countries: Marijuana Arrests in Tennessee” by The Tennessee Tribune is included under fair use.

All other content in “Scope of the Problem” by Ashley Anstett and Elizabeth Pearce is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“Drug Court” is from “A Brief History of Substance Use and Policy Responses in the U.S.” by Patricia Stoddard Dare and Audrey Begun, Introduction to Substance Use Disorders, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 11.11. “The 12 Step Meeting Serenity Club in Sturgis, South Dakota” by Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress is in the public domain.

Figure 11.12. USDA Photo by Preston Keres is in the public domain.

All other content in “Philosophies of Treatment” by Ashley Anstett is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

“Dual Diagnosis” is adapted from “Co-Occurring Mental and Behavioral Health Challenges” by Patricia Stoddard Dare and Audrey Begun, Introduction to Substance Use Disorders, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 11.13. “Proportions of drug users with different ACE exposure levels” in “Does Childhood Adversity Lead to Drug Addiction in Adulthood? A Study of Serial Mediators Based on Resilience and Depression,” by J. He, X. Yan, R. Wang, J. Zhao, J. Liu, C. Zhou, and Y Zeng, Frontiers in Psychiatry, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All other content in “Systematic Strengths and Challenges” by Ashley Anstett is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.