6.3 Mental Health and Treatment

Like many of the topics in this text, mental health is a subject in which you will need to be well-versed in order to be a professional working in this area. Clients are usually dealing with some sort of adversity in their lives, and those circumstances can take their toll on mental health. Struggling with mental illness can also cause a ripple effect of other problems in one’s life—work or school performance issues, relationship problems, substance use, medical problems, and more. Even if you do not plan to be a clinical social worker, counselor or otherwise employed in the mental health field, it is imperative that you feel comfortable working with clients with mental health challenges. You will need to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of many disorders so that you can help clients to get connected to the resources that can best assist them. Clients who are struggling with their mental health may not be able to work toward goals in any social work program until those needs are addressed. This chapter is an introduction to some of the settings and problems you may encounter.

6.3.1 What Is Mental Health?

We have come a long way in the terms we use for various psychiatric conditions, though we continue to modify our terminology seemingly at every step. However, it is not unusual for people still to use words like “crazy,” “unbalanced,” “nuts,” “out of it,” “psychotic,” “insane,” or “sick” to describe those who are dealing with mental disorders. These words reflect a lot of things: misunderstanding, fear, disgust, pity, and more. Many people do not have a firm understanding of mental health and it is just easier to think in these unflattering terms.

You may hear the terms mental illness and mental disorder used interchangeably, and there isn’t necessarily anything wrong with that approach. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition), commonly called the DSM-5, uses the term mental disorder, and that is what we will use in this text. Some people feel that the term mental illness has too negative of a ring to it and may stigmatize people who have been diagnosed with mental disorders. Others are dismayed by the word “disorder” and what it implies about their state of functioning. The DSM-5’s definition of mental disorder is as follows: “A syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning” (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013).

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) is the nation’s preeminent advocacy and awareness organization for people with mental disorders (and you may notice they have “mental illness” right in their name). Their definition of mental illness is “a condition that impacts a person’s thinking, feeling, or mood [and] may affect his or her ability to relate to others and function on a daily basis” (NAMI, n.d., para. 1). Both definitions reflect the same basic idea: a mental disorder (or illness) causes problems in day-to-day functioning, sometimes in multiple areas, and is characterized by unhealthy thinking, emotions, and/or behaviors.

6.3.2 How Common Are Mental Disorders?

As with many important topics, it seems that statistics on the prevalence of mental disorders vary. We are going to stick with two very trustworthy sources. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reports that 20.6% of adults qualified for a mental disorder diagnosis in 2019; about one in four of those disorders (5.2%) would be classified as severe (2020). NAMI (n.d.a) has similar data. Among adolescents (age 13-18), 46.3% qualify for a mental disorder diagnosis at some point during their teen years, and 21.4% of adolescents would meet the criteria for a severe disorder; in fact, the average age at which a mental disorder begins for someone is age 14 (Bellenir, 2012).

The numbers from these two respected sources really are not that far apart, and that is significant. One out of four or five adults has some form of mental disorder each year, which certainly means you will come across many people with many different disorders during your social work career, and you need to be prepared to do a good job recognizing the signs of those disorders and helping to get them the resources they need to overcome their conditions.

6.3.2.1 What causes mental disorders?

There is no simple answer to this question. Here are some of the possibilities:

- Biological: neurotransmitter levels, brain injury, genetics, brain tumors

- Psychological: stress levels, poor coping skills, perfectionism

- Social: socialization, family relationships, abuse, neglect, trauma, economic hardship, loss of a loved one

- Chemical: medications, drugs of abuse, environmental toxins, poor nutrition

Figure 6.1 Mental disorders can be exacerbated by stress which can come from many different sources and manifest itself in several ways.

Mental disorders are not typically caused by a single event or factor, either—often there is an interplay of multiple factors involved as shown in figure 6.1. Just as negative life events can lead to mental disorders, those same disorders can then bring about more problematic events, and the cycle can continue endlessly.

6.3.2.2 What can be done to help people with mental disorders?

This one is easier to answer: in most cases, quite a lot can be done. This chapter will delve into some of the different options available to people with mental disorders—both medications and various kinds of therapy/counseling. Although there are many different disorders out there, there are also a lot of clinicians with expertise in a broad range of areas and plenty of research to show how to handle particular issues. Though mental disorders can be difficult, upsetting, even scary in some situations, there is plenty of reason to have hope for recovery and improvements in functioning. Having a basic understanding of mental health and mental disorders will increase the effectiveness of any human services practitioner.

6.3.3 Historical Context of Mental Health Treatment

At least as early as the 1200s, people with unpredictable and/or unusual behaviors had been subject at times to institutionalization in Europe. As with many other elements of social welfare, a belief in this practice was carried over when Europeans colonized North America (Cox, Tice, & Long, 2016). Without a firm understanding of the nature of mental disorders, at the time people were sometimes believed to be possessed or otherwise cursed in some way, and institutionalization was seen as a practice that was necessary, at times for their safety, and at times for the safety of the community. Sometimes when people were believed to be possessed by demons, they were tortured in efforts to free them from their demonic captors (Zastrow, 2010).

Of course, there were no treatment facilities available when colonists first came to what would become America—the Native Americans did not have formal institutions, and the colonists were working to colonize the country. Therefore, despite the fact that institutionalization was supported in theory by the European colonists, in practice it did not exist. People with mental disorders were, therefore, cared for by their families or to survive on their own.

People in need of care in the 1700s and much of the 1800s were often confined to asylums that were unsanitary and overcrowded, placed in “almshouses with criminals and degenerates,” and sometimes simply imprisoned (Farley, Smith, & Boyle, 2009, p. 153). An early activist and crusader, Dorothea Dix, noticed during her time teaching classes to inmates at the East Cambridge jailhouse that criminals and those with mental disorders were being housed together, as though having a disorder were a crime to be punished. (Wilson, 1975).

Figure 6.2 Dorothea Dix (1802-1887) was an important figure who brought attention to the plight of people with mental disorders being treated terribly; her efforts to reform the system, at a time when women still did not have the right to vote, were impactful.

Dix, shown in figure 6.2, traveled the country and worked to alert the public to the horrifying conditions that people dealing with mental disorders were enduring in these prisons and almshouses, acting as an advocate for more humane treatment. She penned the following account for the Massachusetts legislature:

I tell what I have seen—painful and shocking as the details often are…I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience!…I have been asked if I have investigated the causes of insanity? I have not; but I have been told that this most calamitous overthrow of reason often is the result of a life of sin; it is sometimes, but rarely, added, they must take the consequences; they deserve no better care! Shall man be more unjust than God, who causes his sun and refreshing rains and life-giving influence to fall alike on the good and the evil? Is not the total wreck of reason, a state of distraction, and the loss of all that makes life cherished a retribution, sufficiently heavy, without adding to consequences so appalling every indignity that can bring still lower the wretched sufferer? (Wilson, 1975, p. 122-123)

Dix felt it was not cruelty, but ignorance that caused people to treat those with mental disorders this way, and her passionate recounting of her discoveries to the Massachusetts legislature led to the passing of a bill in 1843 that charged the state with the proper and compassionate care of these individuals (Wilson, 1975). She went on in later years to lobby the federal government to give states land that could be devoted to the construction of facilities to properly care for those in need of mental health care. The attention she brought to the cause was a major impetus for improvements made over the next several decades in the mental health care system; in 1855, the Government Hospital for the Insane (later known as St. Elizabeth’s Hospital) was founded by an act of Congress, and by 1860, 28 of the 33 states in the union at that time had constructed at least one psychiatric hospital (Torrey, 2014).

In the early 1900s, Sigmund Freud’s work brought to mainstream awareness the idea that mental disorders were truly illnesses and people suffering from them needed understanding and proper care in order to have a chance to recover. He pushed a very medical perspective of mental disorders, said that early childhood trauma had caused a lot of these individuals’ emotional and behavioral problems, and encouraged psychiatric diagnosis and treatment of individuals (Greenberg, 2013). This led to a more humanitarian approach, though some of Freud’s specific ideas were misguided (Zastrow, 2010; Greenberg, 2013).

At the same time Freud’s work was gaining steam, social work was also focused on those with mental disorders. Social work was offered as a service in both Manhattan State Hospital and Boston Psychopathic Hospital by 1910, and Surgeon General Rupert Blue asked the American Red Cross to get social workers involved in the federal hospital system in 1919; “by January 1920, social service departments had been organized in forty-two hospitals” (Farley, Smith, & Boyle, 2009, p. 154).

Despite the increased presence of social work in mental health care, conditions still left a lot to be desired. In 1943, conscientious objectors to the war (often religious young men) were put to work in other ways, some in state mental hospitals. They reported scenes much like Dix had seen in correctional facilities:

Here were two hundred and fifty men—all of them completely naked—standing about the walls of the most dismal room I have ever seen. There was no furniture of any kind. Patients squatted on the damp floor or perched on the window seats. Some of them huddled together in corners like wild animals. Others wandered about the room picking up bits of filth and playing with it. (Torrey, 2014, pp. 22-23).

In 1945, following World War II, there was increased recognition of the impact of mental disorders on America’s troops. Government leaders wrote The National Neuropsychiatric Institute Act, a nationwide mental health program, which became the force behind the foundation of the National Institute of Mental Health in 1949 (NIMH) (Torrey, 2014; Cox, Tice, & Long, 2016).

The proposal that the government take a more active role in treating those with mental disorders was fairly revolutionary, including thousands of centers from coast to coast, at least one in each Congressional district. John F. Kennedy, who took the White House in 1961, was powerful allay, as Kennedy’s sister Rosemary had undergone a lobotomy and become incapacitated, though this was not information freely shared with the public at the time. Rosemary had been diagnosed with what was then called mental retardation (now “intellectual disability;” APA, 2013), and that was first on Kennedy’s agenda as President, but shortly thereafter he turned his attention to mental health treatment as well (Torrey, 2014).

By 1961, a committee appointed by the President had decided to push for the elimination of state mental hospitals, the deinstitutionalization of those with mental disorders, and the establishment of a network of community mental health centers (CMHCs), a plan approved by Congress in 1963 (Torrey, 2014; Frank & Glied, 2006). The plan provided federal funds to communities to build such centers and to get them up and running for a few years, with the expectation that each center would become economically self-sufficient thereafter. However, the American involvement in the Vietnam War (1965-1975) severely curtailed the funding Congress had planned to provide, while Congress simultaneously tasked the CMHCs with handling new groups of clients: substance abusers, children, and older adults (Frank & Glied, 2006). With these dual concerns, CMHCs had to keep costs down; this meant higher client-to-staff ratios and a pattern of treating people with less severe problems who were easier to help at a lower cost. This, of course, left those with more severe disorders again to public hospitals (Frank & Glied, 2006).

Deinstitutionalization, while well-intended, ended up having some notable negative effects. as illustrated in figure 6.3. The desire to give people with less severe mental disorders a chance to be maintained in their communities on an outpatient basis wasn’t a bad one. However, the closing of many of the hospitals and the inability of CMHCs to pick up all the slack meant that many people with severe conditions did not actually have anywhere to go that could provide the level of help they required. This is often seen as a major factor in the rise of homelessness among those with mental disorders, as well as the high proportion of the prison population (estimated at up to 20%) that have psychiatric problems (Frank & Glied, 2006; Torrey, 2014). To complicate the problem further, prisoners with mental disorders are less likely to access follow-up care, more likely to end up back in prison than other prisoners, and on average, return to the correctional system faster (Barrenger & Draine, 2013). By the 1990s, leaders in mental health came to the conclusion that while CMHCs were an important piece of the solution, well-regulated and well-staffed state mental hospitals were also an integral part of a system that could fully address the needs of citizens with mental disorders (Farley, Smith, & Boyle, 2009).

Figure 6.3 The deinstitutionalization movement ended up resulting in a lot of people with mental disorders having nowhere to go but to the streets—their problems were too severe to be handled by community mental health centers, but many state hospitals were closing. Being homeless, of course, can also contribute to mental illness.

Most recently, laws have been passed on a national scale to reflect the increased recognition of the importance of treating mental disorders with the same degree of attention and coverage that physical illnesses and injuries receive. The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 and its sister law, The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, require insurance companies to approach the treatment of mental health and addictions in the same manner as medical or surgical treatment—companies may not put stricter lifetime limits, higher co-pays, or higher deductibles on someone’s plan for mental health or addiction treatment than the same person has for most medical/surgical treatments (United States Department of Labor, n.d.). Finally, under President Barack Obama, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 helped to expand Medicaid (now the nation’s number one source of funding for mental health care) and paved the way for more coordination between professionals involved in medical and psychiatric treatment of people with mental disorders (Kuramoto, 2014).

6.3.4 Current Practices and Settings

This next section describes some of the common practices and settings focused on mental health services. The human services professional is likely to encounter people struggling with mental health disorders in almost any setting in which they work.

6.3.4.1 Inpatient and Outpatient Settings

There are two medical practice settings where you as a human services professional are likely to encounter people with mental disorders: inpatient (hospitals, medical & psychiatric) and outpatient (substance abuse centers, mental health clinics, counseling centers). Though there are some similarities in goals and strategies, the differences are certainly worth noting.

Inpatient services in these settings are provided by social workers, counselors and other professionals who work with individuals or groups to provide treatment in a variety of forms. The inpatient worker also works with friends, family, and employers to help the person return to their outside life. The human services professional may advocate and work with other agencies to provide assistance or resources for individuals under their purview of care.

When a patient is ready to leave a psychiatric facility or hospital, the practitioner may connect them to an outpatient clinic. In these settings, outpatient workers assist the individuals or groups in maintaining healthy functioning in their environment through therapy or clinical activities. The social worker or counselor in this setting will conduct therapy or planning sessions, contact outside agencies, and advocate for their client’s best interests.

In addition, you are likely to encounter clients with mental disorders in almost any setting or job. Depressive and anxiety disorders are especially prevalent throughout the population. Any setting that addresses unmet needs such as homelessness, food insecurity, loss and grief, or abuse will include clients that may come to the service with one need identified but may also have treated or untreated mental disorders.

6.3.4.2 Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs)

Many employers have come to recognize that it is to their advantage to handle mental health much like they address physical health, and that giving employees access to mental health treatment and resources not only is the right thing to do, but actually makes for good business. Mental health concerns can be a drain on employee productivity and cause increased absences from work. To that end, more employers have instituted employee assistance programs (EAPs) to link workers with services that can assist them.

EAPs are free for employees to access, and there is an understanding that what’s shared with the EAP is kept confidential from one’s employer. Naturally, if an employee had concerns that their personal struggles would be shared with a supervisor, the individual would be quite unlikely to access EAP services. In some cases, EAPs provide counseling directly, while in others they refer employees to specific agencies, and may cover the cost of a predetermined number of sessions.

EAPs are now required benefits for employees in any federal government workplace (U.S. Office of Personnel Management, n.d.), as well as many state and municipal offices. Among the most common issues addressed by EAPs are:

- Mental health concerns

- Substance abuse/dependence

- Family relationship problems

- Job stress

Apart from these services, EAPs working with particular employers may also offer services for aging issues and elder care, debt and financial assistance, legal advice, nutritional counseling, smoking cessation, child care, and much more (Employee Assistance Group, 2015).

6.3.4.3 The Multidisciplinary Mental Health Team

You may be surprised to learn that clinical social workers are the number one provider of mental health services in the United States—clients seeking assistance with mental disorders have a 60-70% chance of seeing a licensed clinical social worker (Masiriri, 2008; NASW, n.d.). However, clinical social workers are often just one piece in a multidisciplinary team of individuals working together for the coordination of the client’s care. In certain settings like psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment centers, and outpatient mental health clinics, these teams provide a convenient way for clients to get their needed services in one place, with a group of professionals who are all on the same page.

Some of the people with whom you may work on a multidisciplinary team .

- Psychiatrist: A psychiatrist is a medical doctor with a specialty in mental health. Psychiatrists can assess and diagnose clients as well as prescribe them psychotropic medication, shown in figure 6.4, and assess any medical conditions that may be contributing to the issue.

Figure 6.4 Psychiatrists rarely provide therapy on a regular basis, but typically engage in full assessments with clients initially in order to come up with a service plan that may include medication and a referral for mental health counseling. Psychiatrists also work as important parts of multidisciplinary teams in treatment facilities.

- Psychologist: Clinical psychologists on a team may conduct therapy, psychological testing, and/or assess and diagnose clients. They generally have doctorate degrees in their field, but cannot prescribe medication.

- Counselor: A counselor typically has a master’s degree in counseling or a closely related field and may have a credential like LCPC (licensed clinical professional counselor), LMHC (licensed mental health counselor), or LPC (licensed professional counselor). Counselors may engage in assessment, diagnosis, and provision of therapy services.

- Marriage and family therapist: This specialized area of counseling and therapy involves the professional being specially trained in family and relationship dynamics and helping people to resolve emotional and behavioral concerns impacting those relationships.

- Art or music therapist: More and more treatment facilities are employing specialized therapists who can assist in the healing process through the use of art, music, dance, and other means of creative expression and relaxation. These individuals often have master’s degrees in their area of specialty and are sometimes called expressive therapists (Neukrug, 2014).

- Psychiatric nurse: A psychiatric nurse has a nursing degree and license and typically additional schooling to a master’s or doctorate level. Those without an advanced degree can still perform basic tasks like nursing diagnosis and care (Neukrug, 2014). Psychiatric nurses can perform much as counselors, therapists, or clinical social workers do, but also have additional specific training in the medical field. If they are also licensed nurse practitioners or advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), they can prescribe medication as well (American Psychiatric Nurses Association, n.d.; American Association of Nurse Practitioners, n.d.; Neukrug, 2014).

6.3.5 Working with People who have Mental Health Disorders

This section describes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, along with brief descriptions of common diagnoses in the manual. Human services workers will encounter people both diagnosed and undiagnosed in multiple settings and should have a basic understanding of these disorders.

6.3.5.1 DSM-5 Categories and Diagnoses

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is the guidebook of the mental health profession—the most relied-upon source for diagnosis of mental disorders. The fifth edition of the book, DSM-5, came out in 2013 (Coleman, 2014). As with each edition of the text, it was not without controversy. Some of the changes made between the previous edition (DSM-IV-TR) and the DSM-5 were met with skepticism or even disbelief or disapproval in some circles (Wakefield, 2013).

The DSM-5, for better or for worse, is here to stay and will be the guidelines under which mental health diagnosis operates for some years to come. Here are several of the major categories of disorders that compose the DSM-5—those which you will be most likely to encounter in your human services career—and an example of a diagnosis or two in each category.

You will notice that the word “disorder” appears in nearly every category. That word is an important one—think about what it means. Something is not operating as it is supposed to; things are not in working order. It is not unusual for students reading about these disorders and diagnostic criteria to become worried that they may have some of these conditions. You may see some of their behaviors reflected in the lists of symptoms for the varied disorders and start to feel like you might have an undiagnosed disorder. Obviously, if you think you may have one of these conditions, then it may be best to talk to a mental health professional about your concerns. However, before you do, consider the following.

One can have symptoms of a disorder without actually having the disorder. First of all, each diagnosis has a minimum number of criteria that must be met, and sometimes a time frame in which they must have occurred, in order to meet the threshold for having that diagnosis. Secondly, even if one has the requisite number of symptoms to meet a diagnosis, in order for something to be a disorder, it must cause distress or disability in one’s life. In other words, if you have the symptoms of a disorder, but they aren’t causing you problems and you don’t feel bothered by them, then you can rest easy—it is not a disorder.

6.3.5.2 Neurodevelopmental disorders

These are disorders that can become evident in childhood, often before a child begins schooling. They are often co-occurring disorders; it is not unusual for someone diagnosed with one neurodevelopmental disorder also to be diagnosed with another, as with learning disorders and autism spectrum disorders (APA, 2013).

Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders

Schizophrenia is one of the most misused mental health terms in our culture. You may have already been told this in a psychology course, but many people still believe that schizophrenia has something to do with having multiple personalities. That is a myth; schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are notable for the presence of two of the following: “delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking (speech), grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behavior, and negative symptoms” like lack of energy or communication with others (APA, 2013, p. 87 & p. 99).

6.3.5.3 Bipolar and related disorders

Formerly listed as mood disorders, bipolar (and related) disorders were placed into their own category in the DSM-5. In the past, the terms manic depression or manic-depressive disorder were used, although they really are related to a specific variety of bipolar disorders.

Bipolar I is probably what most people think of when they hear the term “bipolar.” It involves the occurrence of at least one manic episode over the course of someone’s life; it does not require the presence of a depressive disorder, though for most individuals with bipolar I, those episodes do occur as well (APA, 2013). As with schizophrenia, there is strong evidence of a genetic link for bipolar disorders, and a first episode often does not occur until the adult years, with some cases not beginning until one is 70 or older (APA, 2013). Here are some examples of people with bipolar diagnosis discussing how it feels to have a manic episode.

- “My thoughts ran with lightning-like rapidity from one subject to another. All of the problems of the universe came crowding into my mind, demanding instant discussion and solution—mental telepathy, hypnotism, wireless, telegraphy, Christian science…” (p. 10)

- “I made notes of everything that happened, day and night. I made symbolic scrapbooks whose meanings only I could decipher…it was all vitally important.” (p. 11)

- “The world was filled with pleasure and promise; I felt great. Not just great, I felt really great. I felt I could do anything, that no task was too difficult…Not only did everything make sense, but it all began to fit into a marvelous kind of cosmic relatedness.” (p. 9-10)

(Sources: Jamison, 1996, Goodwin & Jamison, 1990, Karepelin, 1913, as cited in Mondimire, 2014)

6.3.5.4 Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders are characterized by tremendous fear and/or anxiety out of proportion to any present cause for such emotions. These disorders are more likely to be diagnosed in women (two-thirds of cases) than men (one-third; APA, 2013) pictured in figure 6.5. Anxiety disorders, especially amongst young people, have been on the rise throughout the 2000’s. Preliminary evidence shows an even more dramatic increase between 2020 – 2022 related to the COVID-19 pandemic. There has been a 25% increase in anxiety disorders with females and young adults (aged 20-24 years) most affected (World Health Organization, 2022.)

Figure 6.5. Anxiety disorders are among the most common conditions in the DSM-5, particularly among women.

6.3.5.5 Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders

As you might have guessed, obsessions and compulsions are the key features of the disorders in this category, introduced as a standalone category for the first time in the DSM-5. This is a good example of where the word “disorder” makes a difference. Some of you reading this likely have unusual and pointless habits or odd rules you like to follow (like not allowing different kinds of food to touch on your plate, or trying to avoid stepping on cracks in the sidewalk). However, that doesn’t mean you have a disorder unless your rules or habits cause significant distress or problems in functioning.

6.3.5.6 Trauma and stressor-related disorders

For all disorders in this category, the affected individual must have experienced a traumatic or stressful event which has caused subsequent psychological, behavioral, and/or emotional difficulties. Their behavior may clearly indicate a fearful or anxious tendency after the event, or it may be manifested more as irritability, detachment, or anhedonia (APA, 2013). PTSD is commonly linked with substance abuse, and both sexual trauma survivors and military veterans with PTSD may also report a sensation of numbing to pain when they reexperience memories of their trauma (figure 6.6); at times, this can lead to self-harmful behavior—something we will discuss in greater depth later in this section (Davies & Frawley, 1994).

(Lawhorne-Scott & Philpott, 2013).

Figure 6.6 Posttraumatic stress disorder can cause people to feel like they are re-experiencing a traumatic event from the past, like soldiers having vivid recollections of being in war zones.

6.3.5.7 Feeding and eating disorders

Unusual patterns or significant disruptions of food intake or food-related behaviors are known as feeding and eating disorders. The most commonly known disorders in this category are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and pica.

6.3.5.7.1 Bulimia nervosa

Although it surprises some people to hear, bulimia nervosa is far more common than anorexia nervosa. Bulimia is a combination of recurrent eating binges and behaviors intended to avoid gaining weight (e.g., using laxatives or diuretics, heavy exercise, or self-induced vomiting), typically peaking in adolescence or young adulthood. (APA, 2013).

While anorexia is usually far easier to recognize, people with bulimia nervosa blend in more easily. They are typically of average weight or even overweight, and they go to great lengths to cover up their bingeing and compensatory behaviors (APA, 2013; MacDonald, 2003).

6.3.5.8 Sexual dysfunction and gender dysphoria

Sexual dysfunctions are marked by a disturbance in one’s sexual response or capacity for sexual pleasure. They may be primary dysfunctions—meaning they have always existed—or secondary dysfunctions, those that have occurred after a period of healthy, typical sexual functioning (Carroll, 2013). In order to be a dysfunction, the problem must not go away on its own—typically, a six-month duration is required for a diagnosis (APA, 2013; Carroll, 2013).

The term “transgender” refers to someone whose sex assigned at birth (usually based on external genitalia) does not match their gender identity (based on their cognitive and psychological identification of gender). Some people in this circumstance will experience “gender dysphoria”, psychological distress that results from the incongruence of who one is compared to how others see you. Formerly known as gender identity disorder, gender dysphoria is identified in the DSM-5 in its own category. The condition is more commonly found in those assigned male at birth (0.005 to 0.014%) than those assigned female at birth (0.002 to 0.003%; APA, 2022).

6.3.5.9 Neurocognitive disorders

These disorders involve a change or impairment of previous cognitive functioning. They are signified by decreased mental functioning due to a medical disease rather than a psychiatric illness.

6.3.5.10 Personality disorders

In previous editions of the DSM, one could not be diagnosed with a personality disorder until adulthood. Now, there is an allowance in rare cases to diagnose these conditions in adolescence. Personality disorders are among the most difficult disorders to treat in therapy—they are “enduring pattern[s] of inner experience and behavior that [deviate] markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, [are] pervasive and inflexible,” and are first noticed in the teenage years (APA, 2013, p. 645). If those traits are rigid, pervasive, and cause problematic consequences for the individual, they may constitute a personality disorder.

6.3.5.11 Depressive disorders

Depressive disorders all involve sadness, emptiness, and/or irritability, together with altered thinking and sensation, and have a major impact on the person’s ability to function and interact (APA, 2013). Depressive disorders go beyond “feeling blue”—the condition most commonly involves many individual bouts with severe symptoms, each episode lasting two weeks or more, over a period of months or years (APA, 2014).

6.3.5.11.1 Major depressive disorder

One of the most widely known mental illnesses, major depressive disorder (also called major depression, or simply depression) is diagnosable in approximately one out of every 14 adults and adolescents each year, with higher rates among those aged 18 to 29, and females having 1½ to three times higher rates from adolescence onward (APA, 2013). Some individuals with the disorder have nearly constant battles with depressive episodes, while others may go months or years between them. Nearly half of people begin to recover from an episode within three months of its initiation, with 80% starting to improve within a year. Like some of the other disorders we have discussed, there is a strong genetic link to depression, with a 40% heritability rate.

Other than the family history, age, and gender differences we have already noted, risk factors for depression include:

- Early childhood trauma including sexual abuse history;

- Alcoholism;

- Use of some sedatives and painkillers;

- Extended period of unemployment;

- Urban environment;

- Major life stressors (e.g., divorce, death of a loved one, loss of a job);

- Chronic pain;

- Inactivity;

- Being widowed, divorced, or separated; and

- Tobacco use (Cheong, Herkov, & Goodman, 2006, as cited in Judd, 2008; APA, 2013; Lyons & Martin, 2014; Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2013).

6.3.6 Activity: Sample Self-Rating Scale for Depression

Have you experienced either of the following symptoms almost every day for two weeks or more?

- Feeling sad, blue, or down?

- Lack of interest or pleasure in things you usually do, even those you normally enjoy?

If yes to either 1 or 2, continue. If not, you are unlikely to have depression.

Have you experienced any of the following symptoms almost every day for two weeks or more?

- Poor or excessive appetite?

- Insomnia?

- Increased sleep, or inability to sleep?

- Low energy or fatigue?

- Less activity or verbal communication with others? Slowness or restlessness?

- Increased tendency to be alone, away from others?

- Loss of interest in sex and other pleasurable activities?

- Lack of excitement or pleasure when receiving good news?

- Feeling inadequate, self-critical, or just generally bad about yourself?

- Less efficiency or productivity?

- Lowered capacity to cope with routine responsibilities?

- Poor concentration or difficulty making decisions?

If you answered yes to one or both of the first two questions, and then four or more questions in the second section, you probably have a depressive disorder and should consult a mental health professional for further evaluation.

(Adapted from Klein & Wender, 2005)

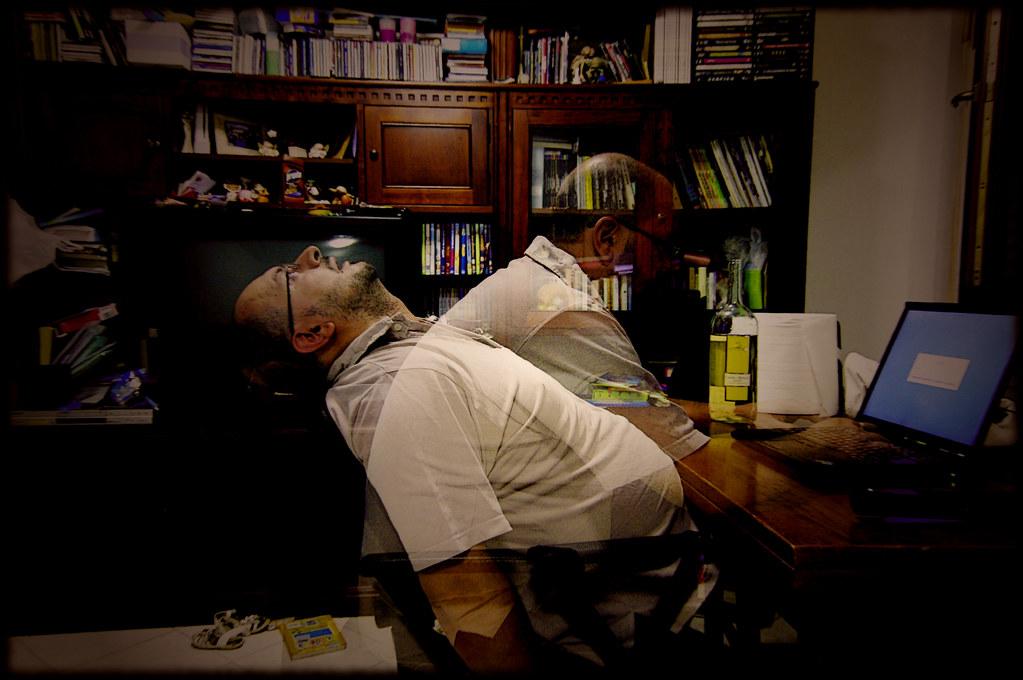

Figure 6.7 Though depression is diagnosed more often in women, men may struggle with it more silently due to societal pressures to be stoic and resilient in the face of stress and loss.

6.3.7 Suicide

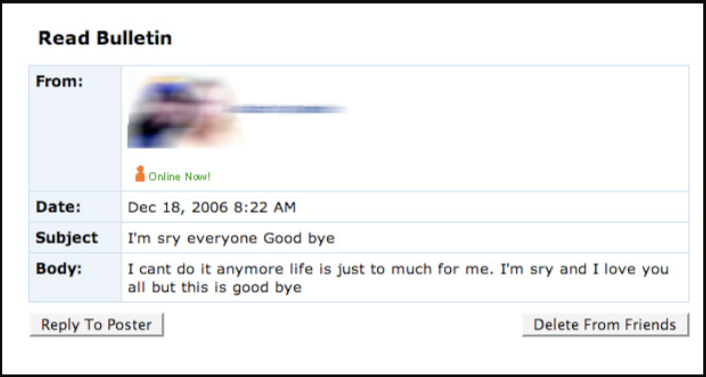

We chose to discuss depression last among the DSM-5 conditions because it is known for its connection to a risk of suicide. In fact, the final diagnostic criterion for major depressive disorder is “Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide” (APA, 2013, p. 161). Depression is the most high-risk mental disorder for suicide, but suicide is a possible behavior for a range of psychiatric conditions. Still, most people with mental illness are not suicidal and will not attempt suicide; only about two percent of people who receive treatment for depression at some point will commit suicide (Barnes, 2010).

Figure 6.8 Threats of suicide should be taken seriously.

Remember, as a mandated reporter, if someone reports feeling suicidal as pictured in 6.8, you need to assess the situation and possibly make a report in order to keep that individual safe. If you have information that someone is intending to harm themselves, you must act on that information. Not only could you face professional consequences for failing to do so, but far more importantly, your client may be quite serious. You need to find out if the client has a specific plan to commit suicide and the means to carry out that plan. If both are present, that is a huge concern and you need to act. Even if there is just a specific plan but no means, you still have a lot of work to do in assessing your client’s mental and emotional state to determine the best course of action.

Men commit suicide more often than women in America (79% of all completed suicides)—in part because they tend to choose more lethal means for their attempts (CDC, 2012). Men’s most common method of suicide is by firearm, whereas women’s most popular is listed as poisoning, which is often done with medication (CDC, 2012; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [AFSP], 2013). The presence of a firearm in a home is an additional risk factor for suicide; it would be wise to assess client access to firearms when dealing with severe depression (Judd, 2008). The only country in the world where more women commit suicide than men is China. Females do attempt suicide more often than men worldwide, however, and no suicide attempt should be taken lightly (Barnes, 2010; AFSP, 2013; CDC, 2012).

The group most likely to commit suicide is middle-age and older adults—those 45 and older. Adults age 45 to 64 and those 85 and up have relatively equal rates of suicide—nearly double that of those aged 15 to 24 (AFSP, 2013). Suicide rates for men are highest among those age 75 and up and continue to increase as they age, while women are at highest risk from age 45-54 (CDC, 2012; Judd, 2008). What’s more, the death rate in adolescent suicide attempts is just two percent; among men over 45 years old, attempts result in death 25 to 50 percent of the time (Stone, 1999). People often think of suicide as something that happens to young people, but as social workers we need to be aware that people of any age are capable of committing suicide.

Be aware of someone exhibiting some of the warning signs of suicide:

- Suddenly showing atypical interest (for them) in firearms or pills;

- Seeming trapped or withdrawing from friends, family, and others;

- Tying up loose ends or giving away cherished possessions;

- Expressing that life is pointless or meaningless;

- A sudden and unexplained change to positive mood after being depressed or withdrawn for some time;

- Unexpected declines in academic or work performance;

- Previous suicide attempts (Judd, 2008).

At any time, if you are worried about the chance of a client hurting themselves, and are unsure what to do, talk to colleagues, and especially your supervisor. This is too important a determination to make yourself if you are uncertain. It is better to act preventatively than take a wait-and-see approach. Suicidality is one of the few reasons (along with being a threat to others) that someone can be hospitalized against their will, provided a qualified mental health professional will attest to the client’s need for such treatment for safety purposes.

6.3.8 Self-Harm

Cutting, burning, scratching, punching, pinching, puncturing, or picking at wounds to prevent healing: there are many methods of self-harm, despite “cutting” being the often-used euphemism. Seventy-eight percent of people who engage in this behavior use more than one method (Adler & Adler, 2011). Self-harm (or self-injury) is a complex behavior that can accompany a number of mental disorders or stressors: depression, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, bipolar disorders, PTSD, negative body image, sexual abuse or trauma, and more. It commonly begins between the ages of 14 and 16 and is seen more often in girls/women, people of any age and gender may engage in this behavior (McVey-Noble, Khemlani-Patel, & Neziroglu, 2006; Plante, 2007). It can be very difficult for some people to understand why someone would engage in self-harmful behavior, especially because many people who do so do not appear outwardly to have mental disorders, and may even be safety-conscious and/or risk-averse in other areas of their life—wearing seat belts, abstaining from tobacco use, etc.

Many people who engage in self-injury say that they do so to relieve negative emotions like frustration, jealousy, loneliness, sorrow, or anger. The physical pain, in a sense, distracts them from their emotional pain, or the neurotransmitter rush that may accompany self-injury helps to counteract the negative emotions (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Walsh, 2012; Plante, 2007). Others report that they feel numb to the world around them, or think they’ve forgotten what it’s like to feel anything—and self-injury reminds them that they can indeed feel, and that they are alive.

Still others have intense negative feelings about themselves and hurt themselves because they feel they deserve it; these individuals (and those mentioned in the previous paragraph) may very well injure themselves in places that will not be seen by others due to being covered up by clothing. Some may be intentionally causing injuries in conspicuous, visible places that they know will get the attention of loved ones or authority figures who will then start some wheels in motion that will get the self-injurer the attention necessary to address whatever is going on (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Plante, 2007; Walsh, 2012). Self-injury is often seen in adolescents and young adults who are exceedingly perfectionistic (academically, regarding body image, etc.) and/or dealing with family dysfunction or divorce (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Walsh, 2012; Plante, 2007). It is also more commonly seen among middle- and upper-class Caucasians than other groups (Adler & Adler, 2011).

When self-injurious behavior is noticed, it is important to address it as quickly as possible. The longer one waits, the more difficult it can be to get treatment, because self-injury can become addictive, may be the only coping mechanism the individual uses for negative emotions, and may be bringing them a lot of attention (though not a healthy sort; Plante, 2007). Ignoring the behavior, or hoping it goes away, may inadvertently send a message that it is nothing to take seriously, or that one is not concerned about the person who is self-injuring. Without intervention, the behavior can escalate as the self-injurer builds up a tolerance of sorts and begins to cut or otherwise hurt oneself more severely (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Adler & Adler, 2011).

An important and common question is whether there is a link between self-harm and suicidal behavior. There is definitely enough of a connection to cause concern. Most people who self-injure do not wish to die, and self-injury should not automatically be taken as evidence of suicidality; however, research has placed the percentage of self-injuring individuals who also display some suicidal behavior at 50 to 90%, and 28-41% of those who self-injure have suicidal thoughts while self-injuring (McVey-Noble et al., 2006). People who engage in self-injury, regardless, are almost certainly suffering from some degree of pain and turmoil, whether they want to die or not. Successful treatment methods exist and can be pursued (Walsh, 2012).

6.3.9 Counseling and Treatment

There is a great deal of counseling involved in human services. Professional counselors need an advanced degree and a certification provided by the state in which they practice. There are also paraprofessional counseling support roles that may be played by human services workers, but the counseling described here requires a license. There are many different approaches to counseling/therapy, and each counselor tends to have a unique style. You may have been to counseling yourself (many mental health professionals have as well—it’s not a bad idea to do so), and you may have had the experience of “clicking” with a particular counselor while failing to do so with another. That is to be expected. Should you become a counselor or clinical social worker yourself, it is unlikely you will “click” with every client yourself.

People who come in for mental health care may be understandably nervous, apprehensive, or anxious about the process. There are a lot of ideas floating around about what counseling is, how counselors and therapists behave, and what one can expect when one enters a counselor’s office. Some believe counselors will push for them to see a psychiatrist and get on medication. Others have heard that they will constantly talk about feelings and try to uncover hidden traumas or repressed memories of the past. People may even think that a counselor will give them the expert advice necessary to fix their problems. But this is not exactly what counselors due. Here are some strategies that counselors can use to learn about their clients and their needs.

6.3.9.1 Counseling strategies

- Speak briefly: The client should be doing most of the talking. Sometimes beginning counselors think they need to be directing the session in a really structured way, and there are situations that do call for that. In general, though, a counselor is doing a good job when the client is talking a lot more than the professional. Counselors should strive to use just a few words, a couple of sentences at most. Sometimes, just one carefully chosen word can prompt a client to continue speaking and to come closer to key insights.

- Use silence: Counselors can make the mistake of thinking that silence is a problem. It can be, if the client is waiting for the counselor to respond to something and nothing is being said. However, silence can be productive. Sometimes a client may pause to gather thoughts, respond to intense emotions, or make new connections and insights about something that has just been said in session. Jumping in and filling the silence may short-circuit the necessary process the client is trying to complete. If a client needs the counselor to speak, it should be apparent through eye contact and body language.

- Plan for termination from the first meeting: The whole point of social work (and counseling) is to make oneself obsolete. We do not want clients to need us forever—we are aiming to empower them on a road to self-sufficiency. With that in mind, a treatment plan should always be in place between counselor and client, with clearly stated goals that can help keep them on track in their work. One question one of your authors was fond of asking his clients in the first session was, “So, how will we know when you do not need to come to counseling anymore?” It was a good way of establishing from the start that this relationship had a purpose and was not intended to be permanent—that the client could succeed and would no longer need counseling at some point.

- Don’t try to solve problems too early: If a counselor offers a solution to the main presenting problem, the client may feel a bit put off that the counselor thinks the problem is that simple to fix. It may make the client feel unintelligent, or at least that they are perceived that way. Clients have generally tried a lot of different methods of fixing their own problem before they come in to see someone; it is important to talk about all those past efforts and brainstorm ideas for future improvement together.

- Don’t ask too many questions: The counseling relationship isn’t a friendship, but it’s not a puzzle or an inquisition either. We do not want clients to feel we are interrogating them. As much as possible, a counseling session should feel like a conversation. Statements can be just as provocative and continue the client’s sharing and processing of feelings and events. Particular questions—like ones that start with “why” or are closed-ended questions—should be used at a minimum. Certain “why” questions can give the impression that a client’s motives or intelligence are being questioned (“Why did you do that?”), while closed-ended questions do not encourage much of a response from the client. Open-ended questions should be the majority of questions asked.

- Pay attention to nonverbal communication: Remember that your client’s nonverbal communication can tell you a lot, especially if it is incongruent with their verbal communication. Pointing out their nonverbals may be educational for them, as they may not even realize how they look. It may also be an indicator to them that you are very “tuned in” to what is happening with them in session. It is similarly crucial to be attuned to our own nonverbal communication and what it communicates to the client—we do not want to show emotion that is inappropriate for the topic being discussed, or send our own incongruent messages.

- Make assessments, not judgments: Remember, it is not the counselor’s job to say something is right/wrong, good/bad, normal/abnormal. Those words generally give the impression of judgment. The counselor should be focusing on psychological assessments rather than moral judgments of behavior, especially since clients may already be feeling judgmental toward themselves.

- Do not try to guess what the client is thinking, feeling, or doing: Beginning counselors (and some experienced ones) may also make the mistake of thinking that if they can guess what the client is thinking or about to say, it looks impressive. However, it is important to allow the client to say what they want to say. It may be very important for them to make a particular statement themselves; they may be acknowledging something openly for the first time. They may need to hear themselves say something to know they can admit to it. Furthermore, if the counselor guesses wrong, it can give the client misgivings about the counselor’s competence or attentiveness.

- Be culturally humble: This is always important. Remember that different cultures may approach counseling in different ways. People may be very reluctant to share personal information and may need time to become comfortable doing so. Each culture has different meanings for nonverbal behavior. Human services workers must continually strive to be more culturally humble. These differences should be understood and respected, along with the counselor having a recognition of their own culture and its influence on the helping relationship and the counselor’s behavior and communication style.

- Use shared vocabulary: Talk the way the client talks. This does not mean to dumb down your language, or to use colloquialisms or slang terms the client uses that you do not normally use (teenagers can see right through an adult trying to act “cool”), but avoid using professional terms, jargon, or acronyms. Speak in a way that is easy for the client to understand. Sometimes this means adjusting your terminology from client to client. You would probably speak differently to a 45-year-old professional than you would to a 13-year-old gang member, even though your basic goal—building rapport in order to work on treatment goals—is the same.

- Show empathy, not sympathy: The counselor should be trying to put themself in the client’s position, to see what it would be like to be dealing with the client’s situations from their own unique perspective. Sympathy, the act of feeling pity or feeling sorry for a client, should be avoided.

- Start where the client is: Finally, the client has to dictate the direction of treatment to a large degree. If the client does not want to work on a particular issue, even if the counselor recognizes it as the major problem that is occurring, then no work can be done. Counselors cannot (and should not try to) force clients to do work they do not wish to do. Pushing against a client’s resistance will often either firm up that resistance or push the client right out of counseling. If the client has a problem he/she wishes to address first, that is where the counselor should start.]

- (Sources: Meier & Davis, 2011; Hutchinson, 2007; Okun, 1997; McHenry & McHenry, 2007)

6.3.9.2 Types of counseling

Counselors can work with clients in a variety of settings, each with its own advantages.

- Individual therapy: One-on-one sessions with clients give them the opportunity to be open and honest about topics that may be more difficult to discuss in a group. The chance to build a solid rapport with the counselor is perhaps stronger in this modality of treatment as well. Sessions for individual therapy typically run 45 to 50 minutes, in accordance with expectations of managed care. Outpatient individual therapy is often done on a weekly or biweekly basis.

- Group therapy: Some problems and types of treatment are better suited for group therapy, which may occur weekly or multiple times per week depending on the level of care. Substance use disorders are a good example of a problem that seems to get better treatment results in group settings. In a one-on-one session, a savvy client may be able to fool a counselor; however, that same client using the same technique may get called out for being dishonest by other members of the group, who can speak a bit more directly than would be proper for the counselor.

Figure 6.9 Group therapy provides opportunities for healing and feeling connected to others with similar difficulties, so clients can know their struggle is shared by others who are also invested in their recovery.

- Family therapy: Sometimes a clinical social worker or other counseling professional will work with a family as a unit. Having the various family members in session can be very illustrative, as interactions between the clients can be observed that otherwise would just have been reported in perhaps a biased way. The counselor can learn from the interactions of the family what processes may be dysfunctional and in need of change, as well as seeing some of the family’s collective strengths that may not have been observable in working with them individually.

- Play therapy: A specialized method for working with younger children, play therapy is a process that helps children to communicate and open up with a therapist about things they might otherwise struggle to put into words. Skilled practitioners of play therapy are able to learn a lot from a child’s methods of play or creative expression that could not necessarily be gleaned from basic talk therapy (McHenry & McHenry, 2007).

There are also many specific schools of thought and families of techniques when it comes to therapy, like cognitive-behavioral, Gestalt, solution-focused, existential, rational-emotive, and more. If you decide to become a clinical social worker, you will have the opportunity to learn a lot more about these various approaches and pick what works best for you.

6.3.10 Working with Women

Without women as clients, we would need a lot fewer social workers, and yet many of our approaches are rather androcentric, focused on men. We have not done as good a job of devoting research to problems that specifically impact women, like postpartum depression and premenstrual dysphoric disorder, or of understanding how specific disorders (like major depression or substance use disorders) manifest differently for women. (To give you an example, a quick search of the EBSCO research database in 2021 revealed 8,730 articles with a mention of postpartum depression, but a whopping 15,041 when the search is for erectile dysfunction!)

We are starting to see more attention paid to these imbalances in treatment knowledge. When women are experiencing infertility issues, for example, we now know that there is increased risk of depression every time menstruation occurs, as it may feel to the woman like another “failure” (Seibring, 2003). This can help us to address a woman’s needs from both a medical and psychological/emotional standpoint.

Critics have also recognized problems in taking treatment approaches that were designed by men from their own perspective of what would be helpful and using those same approaches to help women; for example, feminist practitioners and theorists have been critical of the traditional 12-step approach of Alcoholics Anonymous as it relates to women. The first step involves admitting powerlessness. Women who have stated in groups that they already felt powerless, and that may be part of what led them to abuse alcohol, have been at times “shamed, threatened with abandonment, and called resistant” to the 12 Steps (Matheson & McCollum, 2008, p. 1028). It has been suggested that submitting further to an admission of powerlessness may actually increase women’s insecurity and sense of oppression, putting further roadblocks in their way as they try to recover from a difficult condition. Those who already feel disempowered in their general lives are not likely to find it helpful to start off a program that insists on an admission of powerlessness (Matheson & McCollum, 2008). Powerlessness got them into their addiction in the first place, feminists might say—they need to feel empowered and transformed instead of powerless.

From a macro perspective, we have to recognize that there may be a reason women seem to have higher rates of depression and other mood disorders, and it may not necessarily be physical or neurochemical in nature. “The mental health of women and their low social status are intricately intertwined…Any serious attempt to improve women’s mental health condition must deal with the ways in which their mental health is affected negatively by social customs and cultural considerations” (Wetzel, 1995, p. 177). When women are treated as if they are lesser than men—as they are in virtually every society still today, to some degree—it should be no wonder that they suffer from great degrees of various mental illnesses and may find themselves relegated to lower-paying jobs and a greater likelihood of ending up in poverty. The patriarchal system tells them they cannot succeed, puts limits on their abilities to improve their lives, and then calls the natural emotional and psychological results of systematic oppression a “mood disorder” or “mental illness.”

Men are less likely to feel they live in unsupportive, controlling environments and therefore are more likely to feel comfortable being assertive. Women in counseling may have to be assisted in learning assertive behavior to help them have better chances of achieving what they would like for themselves and their families (Wetzel, 1995).

Wetzel (1995) has several macro-level suggestions that she feels could make a bigger impact on the overall mental health of women than simply continuing to treat individual women’s problems as they present in social work and counseling offices. They include:

- “Raising consciousness regarding gender roles and the importance and worth of every female;” (p. 181)

- “Addressing the fundamental right of every woman to live without fear and domination, whether in the home or society, and to be educated and treated with respect;” (p. 183)

- “Sharing home maintenance and child care with men on an equal basis; restructuring the family and society from a human rights perspective;” (p. 184)

- “Teaching fundamental rights regarding health needs, both emotional and physical, including the individual and mutual need for nurturance, freedom from exhaustion, and participation in decision making, within and outside the home;” (p. 185)

- “Teaching women that both personal development and action, as well as collective social development and action, are essential if their lives are to change for the better;” (p. 186)

- “Engaging in participative social action research, culminating in new policies and laws, as well as participative psychosocial programs for social change” (p. 187).

Addressing women’s individual mental health concerns, while still important, may be like treating the symptom of a wider problem. In order to make a more significant change in the overall mental health of women in the United States and abroad, efforts toward greater equality may be more productive. This is an issue that can be approached from micro, mezzo, and macro angles.

6.3.11 LGBTQ+ Clients

Though there is greater acceptance than ever in America for LGBTQ+ people, substantial prejudice still exists and is at times even socially sanctioned. Having to deal with oppression, disenfranchisement, and discrimination from society at large is difficult, but at times, LGBTQ+ clients have also been dealing with similar behaviors from family and friends. Needless to say, this treatment from strangers and loved ones alike can bring about significant mental health concerns. LGBTQ+ people are impacted by depression at a higher rate than the general population, and counselors who behave in heterosexist or heterocentric ways can become barriers to LGBTQ+ people seeking treatment (Bellenir, 2012).

Barrett & Logan (2002) offer the following tips for working with LGBTQ+ clients in counseling.

- Be aware of your own internalized prejudice: Being raised in a heterocentric society, it is natural for most counselors to exhibit some heterocentrism, often without recognizing it.

- Be prepared to assist clients with coming out: Be supportive and appropriately aware of the potential pitfalls and difficulties that may occur with the process; respect their desire to come out at their own pace.

- Be aware of the effects of prejudice: Recognize that clients have been dealing with negative treatment by society and may be living in a world different from the one you inhabit, if you are heterosexual; they may not have experienced society as a supportive and helpful place, and therefore may anticipate different reactions from others than you would.

- Actively address and combat societal oppression: Think macro! If you want your LGBTQ+ clients to have better mental health functioning, one way to help is to work on changing the environment to reduce those stressors of negative societal reactions and treatment toward your clients.

- Be comfortable and able to talk about sex and sexuality: Do not allow your client to feel like they need to approach the topic of sex indirectly. Be as willing to discuss their sex life and related concerns as you would with a heterosexual client.

- Recognize that domestic violence and substance use does occur in same–sex relationships: Make sure to have a list of LGBTQ-friendly resources at the ready for such situations, and react in the same supportive way you would to any other individual dealing with domestic violence.

- Use the terms clients use: If clients use terms like boyfriend/girlfriend, husband/husband, wife/wife, partner/partner, or anything else in their relationships, follow their lead. Don’t feel the need to guess—if you are unclear what to say, just ask what the client(s) would prefer.

- Avoid overfocusing on sexual orientation or gender identity: Like heterosexual, cisgender clients, LGBTQ+ clients have problems that they do not perceive as related to their sexual orientation or gender identity. Do not feel the need to connect every issue back to those elements of identity.

6.3.12 Self-care

We’d like to add one final thought before closing out this chapter, which is related to self-care. Self-care is discussed more in Chapter 10, but it is important to recognize that working in human services, you will on a daily basis deal with people who are in difficult periods of their life. Frequently, you will encounter clients who are sad, angry, depressed, anxious, frustrated, and hopeless. It will be your job to help them to push through difficult emotions and trying circumstances toward the goals established in the helping relationship. It can be a very rewarding job! It can be said, however, that this is a job that demands your mental health while simultaneously threatening your mental health.

It is a difficult job to often encounter people expressing strong negative emotions. When you are continually taking on sadness and anger and frustration and helping clients have a safe place to unload those feelings, there are days you will leave work absolutely drained, not wanting to do much more than go home and get into bed. Every job probably has days like that, frankly. In human services, it is imperative that you recognize the probability of experiencing secondary trauma, the way that sad, discouraging, or scary emotions can be transferred from client to practitioner. Learning to recognize this kind of trauma in yourself is one step. Learning what kinds of treatment and responses will help you to maintain your own mental health comes next.

Check out the figure 5.20 below to see some specific ideas on how best to ensure you stay mentally healthy while helping clients shoot for the same goal. If you have not done a good job of taking care of yourself, it will be very difficult to be present at work and able to be fully attentive to the client’s needs. This is true of any job in human services—your health impacts the clients’ health.

6.3.12.1 Self-care tips

It is essential for helping professionals to do a good job of maintaining a healthy personal life in order to be able to be most effective in helping people with their lives’ struggles. Here are some specific suggestions of how to accomplish this very important goal.

- Exercise regularly in some way that you enjoy. Physical health impacts your mental health.

- Enjoy an active social life to the extent that you prefer. There’s no need to see friends every weekend, but having contacts with people with whom you can let loose—whatever that means to you—is important to let go of some of the stresses of the day or week.

- Set a firm boundary for yourself for when work ends. Do not constantly be in an “at work” mindset. Do not continually bring work home with you. Make your home your sanctuary, and leave work at work as much as possible.

- Use supervision and consultation to your advantage. When you really need to talk with someone about a case, do it! Seek someone out for that very purpose, whether it is your supervisor on site or a trusted colleague at your agency or elsewhere. But do not spend much of your evenings or weekends at home on this endeavor. Know when to let it go and concentrate on something else.

- Do not give out your personal phone number or email address to clients. They do not need to be able to contact you at all hours. Your agency likely has a crisis or emergency line and someone who is on call for it. Your clients do not need to be able to reach you directly. If you let clients have your phone number or email, you may as well always be at work.

- See a counselor yourself. You do not need to do so constantly, but many social workers see a counseling professional from time to time. It not only helps you to process your emotions and stress and let go of negativity, but it also gives you a renewed appreciation for what clients are going through every time they step into a counselor’s or social worker’s office.

- Make sure you are eating a healthy and balanced diet. Again, physical health impacts your mental health. Don’t skip breakfast and lunch when you have a busy day. If you do not take care of yourself, you cannot attend to others as well.

- Learn how to recognize your own stress signals and respond to them. Do not expect others to do it for you—they are already dealing with their own stressors!

- Know how to say “no.” Social workers are often the kind of people who love to pitch in and volunteer. People will often ask you to do so, knowing you work in the field. If something sounds like it will be fun and you’ll enjoy yourself, go for it! If it sounds like a lot of work and you are already overloaded, do not be afraid to say “no.” The momentary twinge of guilt you feel will be easier to deal with tan the additional task on your stuffed agenda.

- Know how to relax. Spend some time in solitude—running, biking, reading, napping. Get a massage. Bake. Do whatever it is that puts you at peace, and do it regularly.

6.3.13 References

Adler, P. A. & Adler, P. (2011). The tender cut: Inside the hidden world of self-injury. New York University Press.

American Association of Nurse Practitioners (n.d.). What’s an NP? Retrieved from http://www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/what-is-an-np.

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (2013). Facts and figures. https://www.afsp.org/understanding-suicide/facts-and-figures.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (2022). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.) update, American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Nurses Association (n.d.). About psychiatric-mental health nurses. Retrieved from http://www.apna.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3292.

Banks, A. E. (2003). Posttraumatic stress disorder. In L. Slater, J, H. Daniel, & A. E. Banks (Eds.), The complete guide to mental health for women, pp. 214-220. Beacon Press.

Barnes, D. H. (2010). The truth about suicide. Facts on File.

Barrenger, S. L. & Draine, J. (2013). “You don’t get no help:” The role of community context in effectiveness of evidence-based treatments for people with mental illness leaving prison for high-risk environments. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 16(2), pp. 154-178.

Barret, B. & Logan, C. (2002). Counseling gay men and lesbians: A practice primer. Brooks/Cole.

Bellenir, K. (Ed.) (2012). Mental health disorders sourcebook (5th ed.). Omnigraphics.

Bowen, M. W. & Firestone, M. H. (2011). Pathological use of electronic media: Case studies and commentary. Psychiatric Quarterly, 82(3), pp. 229-238.

Brown, L. S. (2003). Women and trauma. In L. Slater, J, H. Daniel, & A. E. Banks (Eds.), The complete guide to mental health for women, pp. 134-143. Beacon Press.

Carroll, J. L. (2013). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (4th ed.). Cengage.

Centers for Disease Control (2012). Suicide facts at a glance. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control (2013). Depression. http://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/basics/mental-illness/depression.htm.

Chiles, J. A. & Strosahl, K. D. (2005). Clinical manual for assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. American Psychiatric Publishing.

Coleman, M. (2014). DSM-5 frequently asked questions by clinical social workers. Practice Perspectives (Winter 2014). http://www.socialworkers.org/assets/secured/documents/practice/clinical/dsm5faq.pdf.

Cox, L E., Tice, C. J., & Long, D. D. (2016). Introduction to social work: An advocacy-based profession. SAGE.

Day, S. X. (2007). Groups in practice. Houghton Mifflin.

Dobbert, D. L. (2007). Understanding personality disorders: An introduction. Praeger.

Employee Assistance Group (2015). Solutions for common issues: Some common issues. http://www.theeap.com/solutions-for-common-issues/.

Farley, O. W., Smith, L. L., & Boyle, S. W. (2009). Introduction to social work (11th ed.). Pearson.

Frank, R. G., & Glied, S. A. (2006). Better but not well: Mental health policy in the United States since 1950. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Frith, C. & Johnstone, E. (2003). Schizophrenia: A very brief introduction. Oxford University Press.

Gnulati, E. (2014, April 11). 1 in 68 children now has a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder—why? The Atlantic. http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/04/1-in-68-children-now-has-a-diagnosis-of-autism-spectrum-disorder-why/360482/.

Greenberg, G. (2013). The book of woe: The DSM and the unmaking of psychiatry. Blue Rider Press.

Hallowell, E. M. & Ratey, J. J. (2011). Driven to distraction: Recognizing and coping with attention deficit disorder from childhood through adulthood. Anchor Books.

Hutchinson, D. (2007). The essential counselor: Process, skills, and techniques. Houghton Mifflin.

Judd, S. J. (2008). Depression sourcebook. Omnigraphics.

Klein, D. F. & Wender, P. H. (2005). Understanding depression: A complete guide to its diagnosis and treatment. Oxford University Press.

Kor, A., Fogel, Y. A., Reid, R. C., & Potenza, M. N. (2013). Should hypersexual disorder be classified as an addiction? Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(1/2), pp. 27-47.

Kristjánsson, K. (2009). Medicalised pupils: The case of ADD/ADHD. Oxford Review of Education, 35(1), pp. 111-127.

Kuramoto, F. (2014). The Affordable Care Act and integrated care. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 13(1-2), pp. 44-86.

Lange, K. W., Reichl, S., Lange, K. M, Tucha, L. & Tucha, O. (2010). The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 2(4), pp. 241-255.

Lawhorne-Scott, C. & Philpott, D. (2013). Military mental health care: A guide for service members, veterans, families, and community. Rowman & Littlefield.

Lyons, C. A. & Martin, B. (2014). Abnormal psychology: Clinical and scientific perspectives (5th ed.). BVT Publishing.

MacDonald, J. (2003). Eating disorders and disconnections. In L. Slater, J, H. Daniel, & A. E. Banks (Eds.), The complete guide to mental health for women, pp. 228-237. Beacon Press.

Masiriri, T. (2008). The effects of managed care on social work mental health practice. SPNA Review, 4(1), pp. 83-98.

Matheson, J. L., & McCollum, E. E. (2008). Using metaphors to explore the experiences of powerlessness among women in 12-step recovery. Substance Use & Misuse, 43(8/9), pp. 1027-1044.

McHenry, B & McHenry, J. (2007). What therapists say and why they say it: Effective therapeutic responses and techniques. Pearson.

McMillin, D. (1991). The treatment of schizophrenia: A holistic approach. A.R.E. Press.

McVey-Noble, M. E., Khemlain-Patel, S., & Nezirogu, F. (2006). When your child is cutting: A parent’s guide to helping children overcome self-injury. New Harbinger.

Mondimire,F. M. (2014). Bipolar disorder: A guide for patients and families (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Morales, A. T., Sheafor, B. W., & Scott, M. E. (2007). Social work: A profession of Many Faces (11th ed.). Pearson.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (n.d. a). Mental health conditions. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (n.d. b). Dissociative disorders. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Dissociative-Disorders.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (n.d. c). Dissociative identity disorder. Retrieved from http://www2.nami.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Inform_Yourself/About_Mental_Illness/By_Illness/Dissociative_Identity_Disorder.htm.

National Association of Social Workers (NASW) (n.d.). Mental health. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/pressroom/features/issue/mental.asp.

Neukrug, E. (2014). A brief orientation to counseling: Professional identity, history, and standards. Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning.

Okun, B. F. (1997). Effective helping: Interviewing and counseling techniques (5th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Plante, L. G. (2007). Bleeding to ease the pain: Cutting, self-injury, and the adolescent search for self. Praeger.

Samenow, C. P. (2012). SASH policy statement: The future of problematic sexual behaviors/sexual addiction. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19(4), pp. 221-224.