2.6 Social Constructivism, Intersectionality, and Cultural Humility

The dimensions of diversity can also be thought of the various social identities that each of us has. They can help us understand the social construction of difference, which is when hierarchical value is assigned to perceived differences between socially constructed ideas.

In the process of forming our own social identities, we connect most easily to people who share the same group membership(s) that we do. According to the Social Identity Theory formulated by Henri Tajfel, we see people who are members of different groups as “others” (McLeod, 2019). In general, we tend to be drawn to others who are more similar to ourselves, whether by appearance or related to other social characteristics, such as age, ability, or sex. This, in combination with the likelihood of overestimating the similarities within groups and the differences between groups, contributes to the social construction of difference.

2.6.1 Social Construction of Race

The social construction of race deserves a special mention, since there is a broadly held public assumption that there are significant biological and genetic differences between human beings based on “race” (meaning observable physical differences such as skin color). In actuality, race is a social construct rather than a biological reality (figure 2.17).

Figure 2.17. Observable physical differences such as skin color are not equivalent to race.

Scientists state that while genetic diversity exists, it does not divide along the racial lines that many humans notice (Gannon, 2016.)In fact, members of the human “race” (all humans) share 99.9 % of their genes National Human Genome Research Institute, 2011). Ancestry and geography likely influence which genes get “turned on” and expressed. What makes our understanding of race complicated is that we have behaved for centuries as if there is a biological difference. Because there has been a longstanding discriminatory practice against people of color, there are multiple impacts today (Berger, 1966).

The reasons for doubting the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction. In this view, race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it, as shown by variations in skin color in figure 2.17.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems of placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. Would you consider former President Obama, White, Black, or multiracial (figure 2.18) He had one Black parent and one White parent. As another example, the well-known golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, but in fact his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter White, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Williams-León, T., & Nakashima, C. L. (Eds.). (2001).

Figure 2.18. Former President Barack Obama had an African father and a White mother. Although his ancestry is equally Black and White, Obama considers himself an African American, as do most Americans. In several Latin American nations, however, Obama would be considered White because of his White ancestry.

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of enslaved people lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other Whites with enslaved people. As it became difficult to tell who was “Black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having Black ancestry would go to court to prove they were White in order to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998).

Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Records in the early 1980s to change her official race to White. Phipps was descended from a slave owner and an enslaved person and thereafter had only White ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “Black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as Black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 Black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was Black). Phipps had always thought of herself as White and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially Black because she had one Black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2015).

2.6.2 Social Construction of Other Identities

Social construction of gender is another widely accepted concept in human services. In other words, the differences that we attribute to the biological designation of female, male, or intersex are actually predominantly constructed by our societal beliefs, and not by biology. The recent broadening of gender identity and expression clearly demonstrates this concept.

Other identities are also constructed via societal agreement. Sexuality, ability, religion, ethnicity, age, and other identities may contain some physical parameters, and certainly contain meaning to the individuals that possess them. Critical to our study of families, however, is the understanding that society creates and reinforces social construction of these characteristics and those constructions favor some groups, discriminate against others, and generally impact the lives of families.

2.6.3 Intersectionality

Articulated by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991), the concept of intersectionality identifies (figure 2.19) the ways that race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously. This means that multiple inequalities affect the life course of any individual. In other words, notions of gender and the way a person’s gender is interpreted by others are always impacted by notions of race and the way that person’s race is interpreted.A person is never received as just a woman, but how that person is racialized impacts how the person is received as a woman. While a White woman may experience some bias or discrimination based on gender, a woman who is Black may experience discrimination based on both race and gender. So, notions of blackness, brownness, and whiteness always influence gendered experience, and there is no experience of gender that is outside of an experience of race. In addition to race, gendered experience is also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability; likewise, the experience of race is impacted by gender, age, class, sexuality, and ability.

Figure 2.19. An idea expressed by many women of color, intersectionality was defined and articulated by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.

Understanding intersectionality requires a particular way of thinking (figure 2.20). It is different than the ways in which many people imagine identities operate. An intersectional analysis of identity is distinct from single-determinant identity models which presume that one aspect of identity (say, gender) dictates one’s access to or disenfranchisement from power.

Figure 2.20. An intersectional perspective examines how identities are related to each other in our own experiences and how the social structures of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone.

An example of this idea is the concept of “global sisterhood,” or the idea that all women across the globe share some basic common political interests, concerns, and needs.[8] If women in different locations did share common interests, it would make sense for them to unite on the basis of gender to fight for social changes on a global scale. Unfortunately, if the analysis of social problems stops at gender, what is missed is an attention to how various cultural contexts shaped by race, religion, and access to resources may actually place some women’s needs at cross-purposes to other women’s needs. Therefore, this approach obscures the fact that women in different social and geographic locations face different problems.

Although many White, middle-class women activists of the mid-20th century United States fought for freedom to work and legal parity with men, this was not the major problem for women of color or working-class White women who had already been actively participating in the U.S. labor market as domestic workers, factory workers, and enslaved laborers since early colonial settlement. Campaigns for women’s equal legal rights and access to the labor market at the international level are shaped by the experience and concerns of White American women, while women of the Global South, in particular, may have more pressing concerns: access to clean water, access to adequate health care, and safety from the physical and psychological harms of living in tyrannical, war-torn, or economically impoverished nations.

An intersectional perspective examines how identities are related to each other in our own experiences and how the social structures of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone. For example, “gender” is too often used simply and erroneously to mean “White women,” while “race” too often connotes “Black men.” As opposed to single-determinant and additive models of identity, an intersectional approach develops a more sophisticated understanding of the world and how individuals in differently situated social groups experience differential access to both material and symbolic resources such as privilege.

2.6.4 Cultural Humility

As our world becomes increasingly diverse and interconnected, understanding each others’ experiences and cultures becomes crucial. Without a basic understanding of the beliefs and experiences of individuals, professionals can unintentionally contribute to prejudice and discrimination or negatively impact professional relationships and effectiveness of services. To understand cultural experiences, it is important to consider the context of social identity, history, and individual and community experiences with prejudice and discrimination. It is also important to acknowledge that our understanding of cultural differences evolves through an ongoing learning process (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

2.6.4.1 Comparing Cultural Competence and Cultural Humility

Cultural competence is generally defined as possessing the skills and knowledge of a culture in order to effectively work with individual members of the culture. This definition includes an appreciation of cultural differences and the ability to effectively work with individuals. The assumption that any individual can gain enough knowledge or competence to understand the experiences of members of any culture, however, is problematic. Gaining expertise in cultural competence as traditionally defined seems unattainable, as it involves the need for knowledge and mastery. Instead, true cultural competence requires engaging in an ongoing process of learning about the experiences of other cultures (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

Cultural humility, which takes into account this ongoing process, is the current model for human services professionals. Cultural humility is the ability to remain open to learning about other cultures while acknowledging one’s own lack of competence and recognizing power dynamics that impact the relationship. The practice of cultural humility requires continuous self-reflection, recognition of the impact of power dynamics on individuals and communities, embracing “not knowing,” and a commitment to lifelong learning. This approach to diversity encourages a curious spirit and the ability to openly engage with others in the process of learning about a different culture. As a result, it is important to address power imbalances and develop meaningful relationships with community members in order to create positive change (Culturally Connected, n.d.)

2.6.5 How Cultural Humility Affects Practice and Research

Using a framework of cultural humility, human services professionals consider context during their interactions with peers, the public, and clients. This provides the ability to view various dimensions of diversity while considering the impacts of prejudice and discrimination. It is also important to consider how cultural practices differ in all settings in which the individual operates. Considering context expands the perspective of culture to include historical context, intersectionality of identities, and the experience of prejudice and discrimination.

Adopting cultural humility is necessary for considering diversity in research. In research, we must consider how questions are asked or which samples are included in a study. In addition, the importance of topics of research to diverse communities must be considered, which may require developing research topics and questions with the populations that are being impacted. Participatory action research is a valuable tool for developing topics in an inclusive way and is a method frequently used to find solutions in the social environment (Kidd & Kral, 2005).

Research should consider the power dynamics between the researcher and the community as well as the dynamics within the community. The use of culturally-anchored methodologies is important for exploring research questions in the appropriate context. Marginalized groups are often compared to a majority group, but these comparisons may not always acknowledge the implications of power dynamics present in such comparisons. For example, many researchers are part of the dominant White European culture. Although likely well-intentioned, it should be acknowledged that they will know less about other cultures, both because of their own identity but also because they are a member of the dominant culture. When developing the methodology, it is important for the researcher to acknowledge one’s own cultural assumptions, experiences, and positions of power. Recognition of these aspects of self will lead to a more careful framing of the research question within context. Finally, it is important to consider where to disseminate research findings to reach wide audiences.

2.6.6 References

Artiles, A. J., Kozleski, E. B., Trent, S. C., Osher, D., & Ortiz, A. (2010). Justifying and explaining disproportionality, 1968-2008: A critique of underlying views of culture. Exceptional Children, 76(3), 279-299. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600303

Artiles, A. J. (2015). Beyond responsiveness to identity badges: Future research on culture in disability and implications for Response to Intervention. Educational Review, 67(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2014.934322

Bell, John (March 1995). “Understanding Adultism: A Major Obstacle to Developing Positive Youth-Adult Relationships” in YouthBuild USA, Sacramento County Office of Education. https://actioncivics.scoe.net/pdf/Understanding_Adultism.pdf

Betancourt, H., & Lopez, S. R. (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48(6), 629-637.

Berger, P. L. & Thomas Luckman. (1966). The social construction of reality. Penguin Books

Brady, Adam (2020, August 4). Religion vs. spirituality: The difference between them. Chopra. https://chopra.com/articles/Religion-vs-spirituality-the-difference-between-them

Cohen, A. B. (2009). Many forms of culture. American Psychologist, 64(3), 194-204.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 140, 139-168.

Culturally connected. (n.d.). https://www.culturallyconnected.ca/#cultural-humility

Gannon, M. (2016, February 5). Race is a social construct, scientists argue. Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/race-is-a-social-construct-scientists-argue/

Goodley, D., & Lawthom, R. (2010). Epistemological journeys in participatory action research: Alliances between community psychology and disability studies. Disability & Society, 20(2), 135-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590500059077

I am proof that bathrooms should be gender-free. (2015). Time. https://time.com/4096413/houston-equal-rights-ordinance-nicole-maines/

Jason, L. A., Richman, J. A., Rademaker, A. W., Jordan, K. M., Plioplys, A. V., Taylor, R. R.,… Plioplys, S. (1999). A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(18), 2129-2137.

Kidd, S. A., & Kral, M. J. (2005). Practicing participatory action research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 187-195. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.187

Kosciw, J. G., Palmer, N. A., & Kull, R. M. (2015). Reflecting resiliency: Openness about sexual orientation and/or gender identity and its relationship to well-being and educational outcomes for LGBT students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55, 167-178.

Matson, J. L., Worley, J. A., Fodstad, J. C., Chung, K.-M., Suh, D., Jhin, H. K., Ben-Itzchak, E., Zachor, D. A., & Furniss, F. (2011). A multinational study examining the cross cultural differences in reported symptoms of autism spectrum disorders: Israel, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1598–1604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.03.007

McLeod, S. (2019). Social identity theory. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html

Morgan, R. (2016). Sisterhood is global: The international women’s movement anthology. Open Road Media.

National Human Genome Research Institute. (2011, July 15). Whole Genome Association Studies. https://www.genome.gov/17516714/2006-release-about-whole-genome-association-studies

National Organization for Human Services. (2015). Ethical standards for human services professionals. https://www.nationalhumanservices.org/ethical-standards-for-hs-professionals

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2015). Racial formation in the United States (Third edition). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Pinderhughes, E. (1989). Understanding race, ethnicity and power: The key to efficacy in clinical practice. Basic Books.

Resnicow, K., Braithwaite, R., Ahluwalia, J., & Baranowski, T. (1999). Cultural sensitivity in public health: Defined and demystified. Ethnicity & Disease, 9, 10-21.

Staples, B. (1998, November 15). “Opinion: Editorial Observer: The shifting meanings of “black” and “white.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/15/opinion/editorial-observer-the-shifting-meanings-of-black-and-white.html

Suyemoto, K. L., & Fox Tree, C. A. (2006). Building bridges across differences to meet social action goals: Being and creating allies among people of color. American Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 237-246.

Tarakeshwar, N., Stanton, J., & Pargament, K. I. (2003). Religion: An overlooked dimension in cross-cultural psychology. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34, 377-394. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022022103034004001

Tervalon, M., & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117-125.

Todd, N. R., McConnell, E. A., & Suffrin, R. L. (2014). The role of attitudes toward white privilege and religious beliefs in predicting social justice interest and commitment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53, 109-121.

They were born identical twin boys, but one always felt he was a girl. (2015). The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/national/2015/10/19/becoming-nicole/

Trickett, E. J. (2011). From “Water boiling in a Peruvian town” to “Letting them die”: Culture, community intervention, and the metabolic balance between patience and zeal. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 58-68.

Williams-León, T., & Nakashima, C. L. (Eds.). (2001). The sum of our parts: Mixed-heritage Asian Americans. Temple University Press.

2.6.7 Licenses and Attributions for Social Constructivism, Intersectionality, and Cultural Humility

Open Content, Original

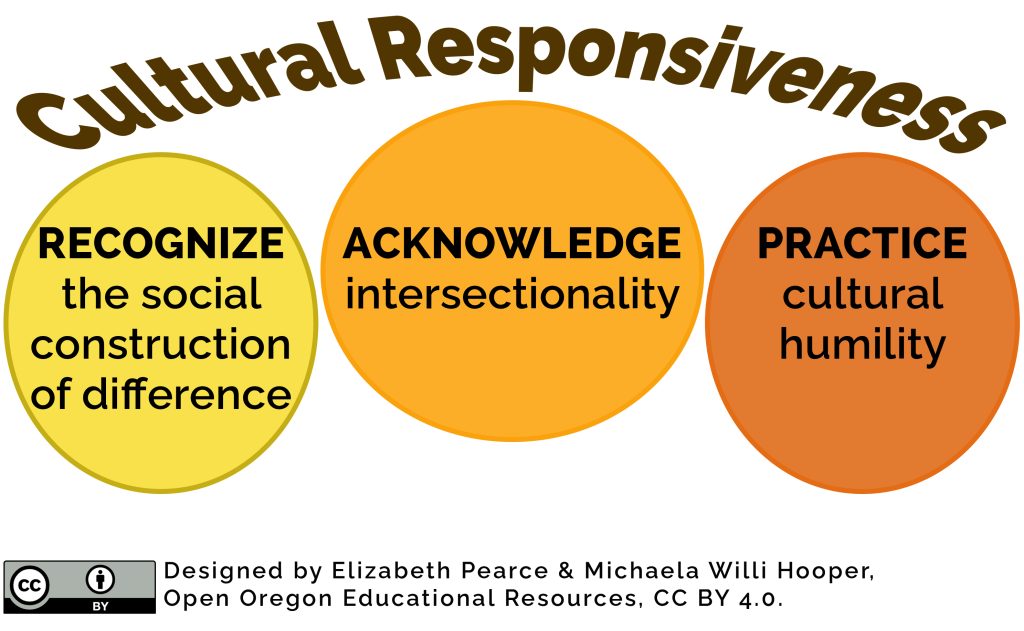

Figure 2.21. “Cultural Responsiveness” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Social Construction of Race” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Adaptation: rewritten for clarity.

“Intersectionality” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “Intersectionality” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, and Laura Heston, UMass Amherst Libraries. License: CC BY 4.0.

Adaptation: rewritten for brevity, reading level, and human services context. New images added.

“Cultural Humility” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “Cultural Humility” by Nghi D. Thai and Ashlee Lien in Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an Agent of Change, Rebus Community. License: CC BY 4.0.

Adaptation: updated language; contextualized for human services; edited for clarity and relevance.

Figure 2.17 Photo by Clay Banks. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 2.18 “Barack Obama on the Primary” by Steve Jurvetson. License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 2.19 “Kimberlé Crenshaw” by Mohamed Badarne. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.20 Photo by Liam Seskis. License: Unsplash License.