1.5 Characteristics, Skills, and Knowledge Areas Needed for Human Services Work

This section introduces the history of human services as a profession. The desire to help others has been present throughout recorded history. However, the development of human services as a profession focuses on using best practices, evidence-based approaches, and theory to help others in the most effective manner possible. There are key characteristics, skills, and knowledge that help human service workers assist their clients as efficiently and productively as possible.

In the early 1950s, Carl Rogers, a prominent psychotherapist, began outlining the approach to helping known as humanistic psychology. Rogers, influenced by previous work of Jessie Taft and Otto Rank on relational theory, believed that the key element in a helping relationship involves the relationship itself. He pointed to three key characteristics that helpers need in order to establish an effective helping relationship: empathy, congruency, and unconditional positive regard.

1.5.1 Empathy

Empathy is often described as putting yourself in somebody else’s shoes. While this description is helpful, empathy in helping is more intentional than “wearing someone’s shoes” implies. Professional empathy is being able to look at the client’s issue or situation from the view of the client. You are attempting to see the world through the other person’s lens, but it does not mean that you can then know exactly how the client is feeling. It does not mean that you agree with this point of view, or that you have had a similar experience to the client. In fact, if you have had a similar experience, it may be tempting to say, “I had the same thing happen.” Remember, even if you have been in the same position, this does not mean you both see the situation the same. Empathy shows that, as another human, you are trying to understand how the client is viewing their experiences and situation. This involves maintaining a judgment-free approach to your work.

For example, let’s think about a human services student interning as an intake worker at a diversion facility for recipients of DUI infractions. The student may hear many versions of “I only had two drinks,” “I wasn’t impaired at all,” or “Everybody I know drives home after parties; I think they singled me out unfairly.” The student may not agree with these statements, but can the student understand how the client may view the situation? Being able to view the situation from the client’s view is critical to working effectively.

Another way of looking at empathy is to consider these four elements:

- Perspective Taking: When you share or take on the perspective of another person, you must also be able to recognize someone else’s perspective as truth.

- Being Nonjudgmental: When we judge another person’s situation, we discount their experience. To take on the perspective of another person, you must put away your own thoughts, assumptions, and biases.

- Recognizing Emotions: Recognizing someone else’s emotion or understanding their feelings requires you to be in touch with your own feelings and to put yourself aside so that you can focus on the person in distress.

- Communicating Understanding: Express your understanding of the other person’s feelings and ask them to tell you more. (Wiseman, 1996.)

1.5.2 Empathy versus Sympathy

Being compassionate with clients involves using empathy rather than sympathy—two behaviors that can be confused. While empathy emphasizes seeing things from another’s perspective, sympathy involves seeing things from your own perspective. Empathy helps build connections between people, whereas sympathy puts one person (the one expressing sympathy) above the other person, creating disconnection.

1.5.2.1 Activity: Empathy or Sympathy?

Dr. Brené Brown is known for her work related to empathy, shame, and sympathy. In this 3-minute video, she gives examples that distinguish empathy from sympathy.

Fig. 1.16. Brené Brown on Empathy vs Sympathy [YouTube Video]

After watching the video, answer the following questions:

- What are the differences between empathy and sympathy?

- How does empathy fuel connection?

- What does it mean to “silver line” something?

1.5.3 Congruence

Congruence (also known as genuineness) has to do with how a helper presents themselves. It is vital that the client feels that the worker is being real with them, rather than just playing a role. And as fellow humans, we intuitively understand this. Think of a time when you were asking someone for help. Your gut tells you when someone is being fake or doesn’t care about the situation. Just as we are sensitive to that sense of insincerity, our clients can pick that up in a human services worker. The solution? Finding the balance between your everyday life and your working life. It doesn’t mean telling your life story to a client, but it does mean being comfortable in your role of helper. This involves the development of boundaries that allow you to be your true self in your working relationships, but maintains a constraint between your personal and professional life. We will discuss self-disclosure in more detail later in this book.

1.5.4 Unconditional Positive Regard

Unconditional positive regard means that everyone has worth and deserves our consideration simply by the fact that they are human. We come to each client and each relationship with a sense of respect and warmth regardless of the client’s past or current attitudes or behaviors. By meeting the client on this level ground, you are inviting the client to work with you as an equal partner in creating solutions. As with empathy, this requires the suspension of judgment of our clients.

1.5.5 Additional Characteristics

Many different human services texts and training materials list characteristics thought to be helpful in the field. These may vary by specific topic (such as group counseling, case management, or substance use treatment), but the following characteristics are generally considered extremely helpful:

- Patience: This characteristic is vital for anyone working with people. It generally takes a long time for clients’ problems to escalate to a place where they are seeking help. It is unrealistic of us to expect that these problems will be solved overnight. The rate of change can be incredibly slow, and attempting to rush the work will generally backfire. Motivational Interviewing is an approach often used for behavior change issues in treatment centers. Dr. Stephen Rollnick, one of the developers of motivational interviewing, describes the importance of patience this way: “Act as if you have 10 minutes, and it will take an hour. Act as if you have an hour, and it will take 10 minutes” (Rollnick, 2013). In our desire to help, we may be rushing along the process in a way that is unhelpful.When we slow down and focus on the client’s needs, the work often goes much more quickly. This video shows Dr. Rollnick talking to a colleague about an example of this in her own work.

- Flexibility: Whenever you are working with other humans, the path to success is not always clear. You may prepare yourself to work with a client on job-seeking strategies, and then the client comes in with an eviction notice. It is important to not be rigid in our expectations of our clients or the work.

- Curiosity: Many of you are probably drawn to this field because of your curiosity about others and the problems they face. It is important to remain curious and never assume you know what a particular client is going through. If you begin losing your sense of curiosity, it may be a red flag indicating burnout, which is related to the final characteristic.

- An Understanding of Self-Care: Often the last thing new workers are thinking about is self-care. However, research supports that human service workers who do not take time to care for themselves will eventually lose their desire to help, and may lead to compassion fatigue and burnout (Newell and Nelson, 2014). Understanding the importance of self-care early on will help you navigate the challenges of this work. Self-care means anything from a 15-minute timeout, committing to leaving your work at work (rather than taking it home), or a week-long vacation. A deeper understanding of healthy self-care is discussed in Chapter 10.

1.5.6 Important Skills for Effective Work in Human Services

As noted previously in the previous section, there are several different levels and types of work in human services. Whether you are working in the micro or macro level (figure 1.5), or working in the Engagement or Evaluation phase (Figure Six), there are common skills that human service workers use. These skills include:

- Communication Skills: An ability to communicate effectively and clearly is a key skill in the human services field. Often we ask clients to tell us very personal information. Our ability to communicate our empathy and regard will go a long way to making the client feel comfortable sharing with us. We also need to be able to communicate effectively with coworkers and the other agencies that may be working with the client as well.

- Documentation: This important part of any human service profession may include chart notes, progress reports, referrals, or assessments. The ability to write clearly and concisely is key for effectiveness. While each specific field in human services may have different documentation requirements, these skills will be important.

- Ability to Ask for Help: Often the people who find it hardest to ask for help are helpers themselves. Helpers tend to think they need to be knowledgeable, and they often have difficulty admitting that they need assistance. However, as noted above, human service workers are often confronted with situations they haven’t prepared for or haven’t faced before. An important part of the work is being able to discuss issues with colleagues and supervisors to help clarify solutions. One of the most powerful statements you can make is this: “I don’t know, but I know who to ask.” None of us can know everything that might be required in our work with clients. In order to be successful and effective, we have to be comfortable asking for input from others.

- Cultural Humility: Being other-centered is an important practice in the human services field. The first step in cultural humility is the awareness that we do not know what it is like to have the social identities and experiences of others. Understanding power dynamics is crucial to practicing cultural humility. In the professional: client relationship the professional already has more power. If the client is also a member of a group that has been marginalized (e.g., being gay, an immigrant, etc.) and the professional is not, this also gives the professional more power. It is especially valuable to be culturally humble in relationships where the person is talking about their experiences as being part of a marginalized group. Being curious and humble, so that we can learn and understand others’ experiences, helps us to grow our own knowledge. Having a culturally humble stance is critical to helping those we serve achieve self-sufficiency.

1.5.7 Important Areas of Knowledge in Human Services

As noted previously in the chapter, there are several different levels and types of work in human services. The knowledge needed for human services has some fundamental areas, but then will be specific to your work, your population, and your own background.

General skills include:

- Awareness of Equity, Inclusion and Diversity: Understanding this lens is one of the foundations of human services. It is referred to specifically in the Human Services Code of Ethics. It is part of our job to address inequities and be aware of structural issues that make accessing services more difficult for vulnerable populations. This will be addressed further in Section VIII of this text. All areas of knowledge need to be understood through the lens of equity, diversity and inclusion.

- Lifespan Development: Understanding the stages of human development is key when working with any age group. What parents experience with a newborn is different from the experience of parenting a pre-teen, for example. The issues facing the elderly are different from those facing a young adult just starting out on their own. Being aware of the ways that systemic oppression and privilege affect development is important. Knowledge of how we develop–biologically, emotionally, and socially–helps us work with our clients appropriately.

- Theories of Effective Helping: As mentioned earlier in the chapter, there are many theories that human service professionals can use to help guide their work with clients. When we offer suggestions or craft interventions, we should have an evidence-based reason, as well as knowledge of our clients culture, strengths. Theory helps us ground our work in effective strategies.

- Knowledge Specific to You and Your Role: These can include both a specific understanding of the population you work with (substance use, houselessness, interpersonal violence are examples) or the role you play in providing services. For example, if you are working as an information and referral specialist, you will probably have a wide knowledge of available programs, but limited depth on any of them. On the other hand, if you are working for an agency that supports LGBTQ+ youth, you will probably have a lot of knowledge about programs that serve that population, but less information about programs aimed at other groups. Another way your knowledge may be specific to you involves your own experiences that you bring to the field. This could include being a member of an oppressed group yourself, having experienced houselessness, or any number of experiences.

1.5.8 Self-Assessment Activity: What Are Your Strengths and Challenges?

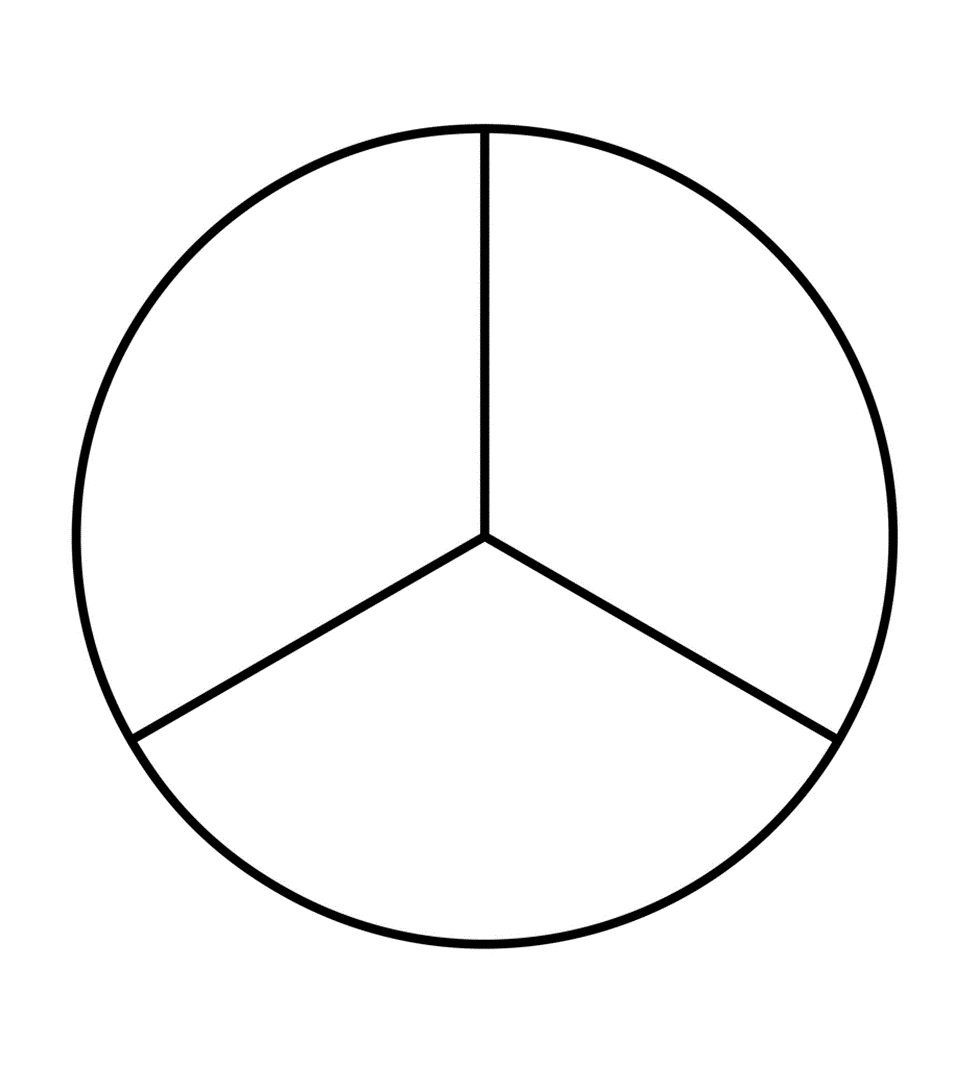

Figure 1.17. Each section of your circle will represent either skills, characteristics or knowledge

Review the list of these attributes from the text, and write those you feel confident about in the matching section of the circle. Now, outside each section, write some of the attributes that you would like to strengthen.

For example, I may feel very confident in my ability to empathize with others, but know that I can be impatient. I would write “empathy” in the “Characteristics” section of the circle, and “patience” on the outside of the circle. You can include other areas of strengths and challenges that you feel are important. For example, you might write “bilingual in Russian” in the section on knowledge, or “understanding of ADA laws” outside that section.

Each of us will have a unique circle that reflects where we are in our journey. It is important to realize that we all have areas that we are strong in, but that we all also have areas for growth. If you are able, compare and contrast your charts with a classmate or two. It can be interesting to see the wide variety of backgrounds that are present.

1.5.9 References

Newell, J. M., & Nelson-Gardell, D. (2014). A competency-based approach to teaching professional self-care: An ethical consideration for social work educators. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(3), 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2014.917928

Rollnick, S. (2013, April 24). Motivational interviewing with Stephen Rollnick, Ph.D.Conference Presentation. Portland, Oregon.

Wiseman, T. (1996). A concept analysis of empathy. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23(6), 1162–1167. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.12213.x

1.5.10 Licenses and Attributions for Characteristics, Skills, and Knowledge Areas Needed for Human Services Work

1.5.10.1 Open Content, Original

“Characteristics, Skills, and Knowledge Areas Needed for Human Services” by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Empathy versus Sympathy” activity by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

1.5.10.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.17 by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0.