10.3 Working with People with Disabilities

My name is Sheila Hoover and I have served people with disabilities for nearly 40 years. Following my bachelor’s degree, I earned a Master’s degree in Counseling (Rehabilitation emphasis) at Gallaudet University. In 1990, I was hired as a Rehabilitation Counselor with Oregon’s Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) program. I worked with Deaf clients and people with many other types of disabilities. Since 2003, I have worked in the VR Administration Unit, providing technical assistance and guidance to people both inside and outside state government. In addition to my role at Oregon VR, I have trained thousands of people in academic and in-service settings. I am a Peer Reviewer for the federal Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA), and help award millions of dollars in grant funding to VR agencies, universities and research institutions across the US. I am also a nationally Certified Rehabilitation Counselor (CRC) and a Certified Vocational Evaluation Specialist (CVE).

As a person with acquired disabilities, I am especially aware of the problems and challenges that the Disability Community faces, even with gains in legal and social status over the past 50 years. I believe working in the Human Services field–at any level–is the best route to achieve equity and parity for people with disabilities.

10.3.1 What IS a disability?

The Disabled Community is the largest minority group on the planet…what people don’t realize is that not only are we the largest group, but we’re also the only minority group that you can join at any time. You’re just one bad bike ride away…

–Josh Blue, Comedian (2021)

For as long as there have been people, there have been people with disabilities. Some cultures consider people with disabilities to be highly spiritual and influential. Others view disability as a curse to the community and expect families to send disabled people to institutions where they can receive the “special care” the culture presumes they need. In his extensive literature review on international societal expectations and disability, Munyi (2012), outlines historical and cultural changes in perception of disability. From the ancient Greeks to the current day, the way cultures and communities perceive their members who have disabilities has a monumental impact on how those individuals are integrated into or excluded from society.

Disability is used to describe a broad range of physical, emotional and cognitive conditions. Disabilities can be congenital or acquired later in life, and they occur due to a wide variety of causes. While Human Services professionals are not expected to have the same level of understanding of physical, cognitive and emotional disabilities as medical doctors and psychologists, it is important that we have a foundational understanding of what type of disability a client is experiencing, when it occurred and how that disability affects their everyday life.

10.3.2 Genetic conditions

Genes hold DNA, which is the cells’ instruction manual for making proteins. Proteins do most of the work at the cellular level; they may move molecules from one place to another, build structures, break down toxins, and do other maintenance jobs. When a mutation—a change in one or more genes—happens, it causes the instructions for making a protein to change. Mutations can prevent the protein from working properly or cause it to not exist at all. Genetic disorders are the result of one or more genetic mutations. Since embryos receive genetic materials from both parents, it is possible to inherit disorders due to one or both parents’ DNA. If the disorder expresses itself at birth, that person is said to have a congenital condition. If the disorder occurs later in life, it is classified as an acquired condition. In both cases, the individual has a hereditary disorder. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) classifies genetic disorders into three types:

- Single-gene disorders, where a mutation affects one gene. Sickle cell disease is an example.

- Chromosomal disorders, where chromosomes (or parts of chromosomes) are missing or changed. Chromosomes are the structures that hold our genes. Down syndrome is a chromosomal disorder.

- Complex disorders, where there are mutations in two or more genes. Often lifestyle and environment also play a role. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer due to mutations in the BRCA1 & BRCA2 genes is an example.

A person can experience multiple types of genetic disorders as well.(Queremel Milani & Tadi, 2022)

10.3.3 Trauma-induced conditions

Trauma, whether physical or emotional, is a common cause of disabling conditions. These are acquired disabilities. A traumatic event–a motor vehicle accident, a natural disaster, physical or sexual assault–occurs and the body and brain are affected negatively. Disabilities resulting from trauma often have both physical and psychological impact, so individuals with these disabilities frequently have long and difficult recovery processes. The physical disability is usually easily identified and treated. Unfortunately, the co-occurring psychological disabilities–Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression–and cognitive impacts are often initially overlooked by practitioners and intentionally downplayed by the person who experienced the traumatic event.

This reaction by the individual is highly likely to be caused by society’s tendency toward stigmatizing, being prejudiced about and discriminating against people with mental health conditions. Roessler (2016) states that consideration of the stigma of mental disorders was theoretically developed during the middle of the 20th century and became empirically accepted in the 1970s. “There is no country, society or culture where people with mental illness have the same societal value as people without a mental illness. (Goffman, 1963)”

The American Psychiatric Association reports that less than 50% of people experiencing mental health disorders receive treatment for those disorders, and suggests that multiple layers of stigmatization–public, institutional and self-focused as described in figure 10.1–have significant impact on individuals’ tendency to seek treatment, and to cause worsening symptoms prior to treatment being started.

10.3.3.1 Types of Stigma

| Public | Self | Institutional | |

| Stereotypes & Prejudices | People with mental illness are dangerous, incompetent, to blame for their disorder, unpredictable | I am dangerous, incompetent, to blame | Stereotypes are embodied in laws and other institutions |

| Discrimination | Employers may not hire them, landlords may not rent to them, the health care system may offer a lower standard of care | These thoughts lead to lowered self-esteem and self-efficacy: “Why try? Someone like me is not worthy of good health.” | Intended and unintended loss of opportunity |

Figure 10.1 summarizes the differing ways stereotypes and prejudices affect individuals with mental health disabilities. The response to those stereotypes results in discrimination against people with mental health disabilities and low self-esteem and self-confidence for mentally disabled people.. Source: Borenstein (2020), adapted from Corrigan, et al.

For those whose disabilities occurred in military service, co-occurring traumatic physical and psychological conditions are also impacted by the stigma associated with mental health diagnoses. It is estimated that that 14% to 16% of U.S. service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq have been diagnosed with PTSD or depression but researchers caution: “Other issues like suicide, traumatic brain injury (TBI), substance abuse, and interpersonal violence can be equally harmful in this population. The effects of these issues can be wide-reaching and substantially impacts service members and their families. While combat and deployments are linked to increased risks for these mental health conditions, general military service can also lead to difficulties. (Inoue, et al. 2022)”

10.3.4 Time of Diagnosis is Critical

Conditions that are not caused by either genetics or trauma are the most prevalent types of disabilities. They may be present at birth or express themselves later in life. This is the case with physical disabilities as well as with psychiatric and cognitive disabilities. Knowing the age of onset is important for Human Services professionals, because it gives us an idea about the length of time the person has had to develop coping strategies and learn effective approaches to problems the condition brings to their day-to-day lives. In general, the earlier the condition is diagnosed, the greater understanding and acceptance the person will have about it, and potentially, the stronger their support system will be. Diagnoses which occur in childhood and adolescence may allow the person to receive support services through Special Education programs to allow them to learn more effectively at school. Diagnoses in early adulthood and middle age may trigger eligibility for academic accommodations or for workplace accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

10.3.5 Diagnosis vs. disability

What is the difference between a medical or psychological diagnosis and a disability? Dictionary.com states a diagnosis is “the process of determining by examination the nature and circumstances of a diseased condition(Random House Inc., 2022).” The diagnosis indicates what part of the person’s physical or mental health does not meet the accepted standard for “healthy” function. Diagnoses allow health professionals to determine what treatments the person with the diagnosis should follow. Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is a diagnosis that alerts health care professionals and the individual that the body is not processing food properly and the individual needs to monitor their blood glucose levels in order to manage the diagnosis.

A Disability is “a physical or mental handicap, especially one that hinders or prevents a person from performing tasks of daily living, carrying out work or household responsibilities, or engaging in leisure and social activities(Random House Inc., 2022).” If a person with T2D does not follow the recommended diet and take the correct dose of insulin prior to eating, they can develop infection, nerve damage and eventually death of tissue (gangrene). This starts most frequently in their feet and legs and often requires the dead tissue to be amputated. It is at this point that the person moves from having a medical diagnosis that they must manage to having a disability. The amputation of a foot or leg makes it difficult for them to stand and walk (with or without prosthetics, wheelchairs or other adaptive equipment). It can lead to difficulty cleaning or otherwise managing their household. If their job requires standing for long periods or using their feet to operate machinery they may be unable to do the work they have done previously.

While it is possible to have a medical or psychological diagnosis and to experience no limitations to participation in society, most people with disabling conditions do experience those limitations. It is the impact of the limitations caused by the condition and the environment that establishes the presence and severity of a disability.

It is critical that the difference between disability and handicap is understood, especially for those who are entering the helping professions. A disability is the physical, emotional or cognitive condition that an individual experiences, which limits their ability to participate fully in society. A handicap, however, is a barrier which occurs because of the environment the individual must navigate. For example, a wheelchair user may have one or more of several disabilities which limit their mobility, but they are not handicapped until they are met with stairs or narrow passages their wheelchair cannot get through.

The way people experience disabilities varies wildly from individual to individual. Even if the medical or psychological diagnosis is exactly the same, no two individuals will experience that condition identically. Individual experience of disability is heavily impacted by the way the person has been raised; this relates not only to the family’s cultural, religious and political values, but to how the individual’s disability-related needs are addressed and whether the individual had role models with disabilities to inspire their developing concept of who they are and what is possible for them to achieve.

As American society and values have evolved, the way disability is viewed has changed. Prior to the end of the 20th century, the language used to describe individuals or groups with disabilities was focused on eliminating or “fixing” the medical condition and the barriers it posed (medical model of disability), not on the impact on the individual person and their status in the disabled community (social model of disability).

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that US citizens were legally given the right to services that assisted them to become employed after sustaining a permanently disabling condition. Two federal laws were the basis for the creation of the vocational rehabilitation programs for veterans, in 1918, and for those whose disabilities came about due to non-war-related accidents or injuries, in 1920. As the civil rights and equal rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s gained momentum, disability rights activists applied lessons learned to their efforts to ensure equal access to American life for anyone with a disability.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 brought sweeping change and was the first law to require equal access for people with disabilities by removing architectural, employment, and transportation barriers. Sections 501 and 503 of the law prohibit federal agencies from discriminating against individuals with disabilities. Section 504 extends that prohibition to any organization receiving federal funds. Reauthorizations of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 occurred periodically, with the most recent version of the law, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), being enacted in 2014. Protections for physical access, education, employment, and civic participation were established for the rights of people with disabilities in non-governmental settings did not get codified until the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990,

Figure 10.2 provides an overview of the history and impact of the Disability Rights movement, which played a critical and substantial role in the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Americans with Disabilities Act and many other local and national laws and policies.

Figure 10.2. Advocating for the rights of people with disabilities is one part of our country’s efforts to ensure civil rights for all.

10.3.6 A Word about Language and Disability

The way we write and talk about disabilities has changed significantly over the years. As someone entering a professional field where odds are quite high that you will cross paths with people with disabilities, it is critical that you are aware of the battle that continues over how to refer to members of the Disability Community. This is a hot topic both inside and outside the disability services world and will continue to be something human services professionals will need to stay informed about as language continues to evolve.

In an effort to move from using the term “the disabled,” parents, educators, lawmakers and others (most of whom did not have disabilities) used terms intended to soften the negative impression of disability. “Differently abled,” “Handi-capable,” and “Special Needs” are still used, especially in connection with services for children and in primary and secondary education. While some people in the Disability Community find nothing wrong with them, overall they have fallen out of favor because they oversimplify the issue. We’re all differently abled, whether or not we have disabilities. Using these terms communicates that people with disabilities are “not normal,” when living with disabilities is “normal” for them.

As American society moved from labeling disabled people with their medical diagnoses, there was a social movement in the late 20th century to use “person first” language. Person-first language emphasizes the fact that the individual is a person, not a diagnosis, and advocates the use of phrases like “person with autism” when discussing individuals who have disabilities.

The debate about whether “person-first” or “disability-first” language should be the norm continues. Language is, after all, a reflection of society, culture and history, and it changes rapidly. In recent years, there has been a push by many members of the Disability Community to shift from “person-first” to “Identity-first” language (“Autistic person,”). Identity-first language advocates acknowledging disability as a part of what makes a person who they are. Disability isn’t just a description or a diagnosis; it’s an identity that connects people to a community, a culture and a history. (Ladau, 2021). You will find both person-first and identity-first language used throughout this section,as illustrated in figure 10.3.

Figure 10.3 This video clearly summarizes the “person first vs identity first” distinction.

Those entering work in the human services field should take care to be respectful of individuals’ preferences. When in doubt, ask the person you are working with what their preference is, then take care to use that approach when you are communicating both with them directly, and about them to other professionals.

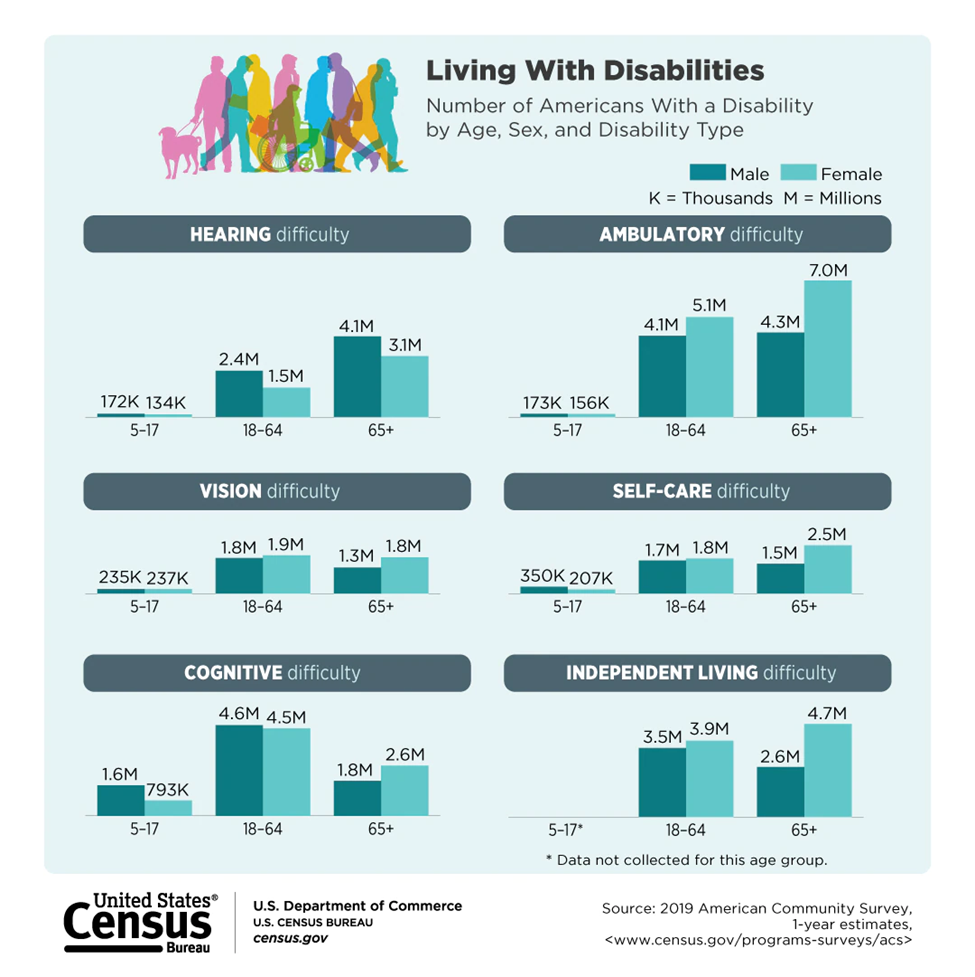

10.3.7 Disability Prevalence in the United States

For all the progress made in data collection related to population, there remains no accurate way to determine exactly how many people with disabilities live and work in the United States. The US Census does not have any questions people must answer that are directly related to disabilities, so determining the number of people in the US who have at least one disabling diagnosis can only be done through estimation. Americans’ rights to and concerns about privacy remain a barrier to gathering accurate data on disability prevalence and the impact of any regional or socioeconomic status on the Disability Community. A rough estimate by scientists is that there are 67 to 83 million US adults with a disability (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2021). Using data from the 2010 US Census, researchers have estimated that 1 in 4 adults in the US have at least one disabling condition; members of marginalized communities in addition to disability were found to have gaps in education, income and employment compared with the majority community. (Varadaraj, et al., 2021)

Exact numbers are not likely to become available in the decades ahead, as disability disclosure is a very personal choice. Most people with disabilities have a range of information they are willing to disclose, based on the entity requesting that data. While this variability is frustrating to those who attempt to capture accurate and exacting data for legislative, civic, employment, medical and related purposes, until data from the 2020 US Census is finalized, it is acceptable to use the American Medical Association’s 2019 estimate of 1 in 4 Americans having at least one disability.

Figure 10.4 provides further detail about the estimation of Americans whose disabilities limit them in various tasks or activities. The data is broken down by age and gender.

10.3.8 Psychosocial Aspects of Disability

While many disabilities cause physical issues—either due to the disability itself or as a result of treatment for that disability—all disabilities have psychosocial impacts. Psychosocial issues happen when the person with the disability interacts with a physical environment and/or with other people, and often has a negative experience. Psychosocial aspects of disability vary based on the type, severity, duration and a prognosis of that disabling condition, as well as on the strength of the individual’s social support system and the individual’s self-esteem.

For example, as an individual is diagnosed with an acquired disabling condition such as cancer, they may become depressed or develop other mood disorders. They may begin mis-using alcohol or drugs, either of which can lead to addiction disabilities. They may have high levels of frustration and difficulty managing their emotions as they attempt to adapt to the limitations the disability imposes, with or without disability-related accommodations. They may also deny or downplay the presence or impact of the disabling condition in an effort to be seen as “normal.”

Psychosocial impact is also significant for people who were born with their disabilities. This group is often overlooked in discussions on this topic because authors and practitioners presume that congenital disabilities are something the person has experienced their whole life so should be accustomed to. This presumption overlooks the fact that psychosocial issues are caused by interaction with the environment or with other people, regardless of the length of time the person has experienced the disability.

The way children and teens with disabilities interact within school and their communities is very different from their non-disabled peers. They are often sheltered and expected to be dependent on parents and service providers. They may lack access–either due to physical barriers or to mental or emotional limitations–to events or activities their peers take for granted. These experiences all leave their marks and the cognitive and behavior patterns used to cope with them can carry over to adult life, resulting in significant difficulty in making friends and dating, succeeding on the job and reaching personal goals around relationships, marriage and parenthood.

The groups that likely struggle the most with psychosocial disability issues are people who have progressive disabilities and those whose disabilities follow a pattern of exacerbation and remission. Progressive disabilities, such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig Disease), become increasingly severe over time. The disabled person must continually adapt physically, mentally, emotionally and socially, based on the progression of their disability. Individuals with this disability pattern often go through stages of grief the same way people grieve when a friend, family member or other important person dies. People with exacerbating and remitting disability features must learn to cope with disability barriers that suddenly change; this can be an increase in severity of one or more symptoms, a sudden decrease in limitations, or a brand new limitation.

Multiple Sclerosis, which is caused by a person’s immune system eating away at the protective covering of nerves in the brain and spinal cord, is a good example. People with this disability may have months or years without any changes in their symptoms, then overnight have significant increases in pain or fatigue and can also suddenly experience partial or total vision loss and/or impaired coordination, as communication between the brain and the rest of the body is increasingly disrupted. For both groups, “adjustment to disability” is a moving target because the issues they face are constantly changing.

Disability diagnosis, wherever it occurs, results in the individual and their support systems (family members, friends, medical providers, etc.) experiencing a loss: the diagnosis changes the individual’s expectation for their future and may cause members of their support system to change how they interact with the newly-diagnosed individual. The severity of these changes may result in the individual reevaluating who is and who is not in their support system moving forward, or in some members of the support system being moved in or out of the group the individual relies on most .

10.3.9 Where do disability services happen?

Because human services professionals work in so many different places, “disability services” are not limited to organizations or agencies that specialize in services related to people with disabilities. Any person who calls, emails or comes in the door may be a person with disabilities. Because the majority of disabilities are invisible, the person likely will not “look” like a disabled person. Since the ADA passed in 1990, government agencies, businesses and community organizations have made substantial and noticeable efforts to make their physical locations, websites and advertising materials more accessible to people with disabilities. Many organizations, including local and state government programs, now consider disability to be part of their diversity, equity and inclusion efforts, so are working to make their services and their workplace culture welcoming to people with disabilities.

All that said, there are many settings where services targeted to disabled people are the focus of the organization. These are often government or non-profit organizations, but can be for-profit businesses as well. Some focus on housing and personal safety issues. Others target employment or provide programs designed to help people with disabilities develop skills that will allow them to live as independently as possible. Still others provide legal advocacy or provide federal funding for basic living expenses. Examples include (but are not limited to):

- Independent Living (IL) Centers, which provide advocacy and skills training for people with disabilities to live as independently as possible in their communities.

- Assistive Technology organizations, which focus on providing tools, devices, computer hardware and software that can help people with disabilities live and work as independently as possible.

- Vocational Rehabilitation (VR) agencies and their contractors, which assist eligible people with any type of disabilities to prepare for, obtain and keep jobs in their communities, and to advance in their careers if there are disability-related barriers. This category includes State VR, American Indian VR, Veterans’ VR and Workers Compensation programs.

10.3.9.1 Meeting your Clients’ Disability-Related Needs

Because of the diversity of disabilities and the sheer number of possible limitations those disabilities create, there is no way anyone working in human services roles can be instantly able to meet all their clients’ disability-related needs. Even if ten people with the same medical diagnosis came in to request services, their needs would all be different because the way they experience the diagnosed disability is different. Because of this, human services professionals should tailor the service plan to the individual, not to the disability.

Learning more about specific disabilities and how they impact people can be very helpful. Depending on your clients with disabilities to educate you about disability causes, effects, social issues, and limitations is unethical and inappropriate. On the other hand, practicing cultural humility and talking with them about the way their disability affects them is absolutely essential. If you are unfamiliar with the disability diagnosed, seek information about it from credible sources. Information from the World Health Organization, the federal or state government, peer-reviewed professional journals and disability-related organizations will be much more accurate than a social media post or a personal blog.

Although using information created in the recent past is generally best, it can be difficult to obtain current research and information about low-incidence disabilities such as those which:

- are caused by genetically-based diseases and syndromes such as Cystic Fibrosis or Sickle Cell Disease,

- involve sensory limitations: blindness and vision impairments, Deafness or hearing losses, and DeafBlindness,

- are reemerging diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and influenza,

- are emerging infectious diseases, like COVID-19 and all its variants.

With advances in technology and medicine, some disability-related limitations can be reduced or eliminated. Devices intended to remove barriers for one group of people with disabilities may become so popular that everyone uses them, regardless of disability status. Ramps installed to make it possible for people with mobility-related disabilities to avoid stairs are used by people pushing strollers, moving materials with hand trucks or carts, and non-disabled people who just find the ramp easier to use. Captions on movies, videos and TV shows are used by people of all ages who are learning to read English, people who do not want the sound to disturb others near them, and also by people with hearing losses of all levels.

10.3.10 Systemic challenges and strengths

The human services system consistently faces systemic challenges in the effort to serve all who need assistance and advocacy. When disability is present, the client often will be receiving services from a variety of programs, each with their own priorities and requirements for the client’s time and attention. For example, Agency 1 requires the people it serves to participate in skill building classes scheduled from 1 PM to 5 PM three days a week. Agency 2 requires clients to submit 20 job applications per week but limits online applications to a maximum of 5 per week. Agency 3 provides childcare support on weekdays but requires parents to pick up their children by 5:30 PM; the shared client’s children are cared for in a location that requires a mass transit trip that takes 60 minutes each way. In these situations, service providers fail to consider the disabled client’s physical and mental stamina and the tasks other programs require of the client for continued support. Intentional or not, this stacks the deck against the client.

Many working professionals in human service programs have limited knowledge about how to make their services fully accessible to people with disabilities. A power door opener on the main entrance is great for those with mobility-related disabilities, but if the path to the meeting room is less than 3 feet wide, there are steps between the front door and the meeting area, or the meeting room doesn’t have enough space for the person’s wheelchair to fit in with a closed door, the individual’s needs have not been met. Having the ability to adjust lighting to be brighter or dimmer, meeting in a place without a lot of visual distractions and allowing the client to choose the best seat for their disability-related needs–which could be facing away from the window or closest to the door–are additional ways of ensuring people with disabilities feel welcome, respected and safe.

10.3.10.1 Disability etiquette

Etiquette is the set of rules or customs that control accepted behavior in particular social groups or social situations, and which convey respect, consideration and honesty between individuals. Codes of social rules for behavior have been observed and practiced since the 3rd millennium BCE. In the early 20th Century, Emily Post became the most well-known American source regarding how individuals should behave in “polite society.” There is also an etiquette for interacting with people with disabilities. These standards, when practiced, demonstrate the same respect to others as the historical rules of behavior in “polite society” did. Disability etiquette validates the independence and autonomy of a disabled person and shows respect. Each person you interact with will have their own preferences, but overall, practicing disability etiquette will demonstrate to those you interact with that you recognize and respect them as an individual.

The video below provides disability etiquette information from the perspective of people with various disabilities.

10.3.10.2 Disability etiquette activity

Watch this video, How to Treat a Person with Disabilities, According to People with Disabilities.

Then discuss the following questions:

- What are some of the do’s and don’ts of asking questions according to the participants from the video?

- How does disability etiquette relate to other forms of etiquette?

- How does disability etiquette relate to the practice of cultural humility

- What is inspiration porn?

If you are unsure of how to interact with someone with a disability, ask them how they would like you to do so. If you make a mistake, apologize and ask how they would prefer you resolve the issue. You are both human, and learning from mistakes is a common experience, regardless of whether or not we have disabilities. This, and other behaviors, can contribute to you becoming an “ally” as shown in Figure 10.5.

When communicating about disabilities and issues in the Disability Community, it is essential we actively discourage the practice of highlighting the Disability Community as being “inspirational” solely due to their disabilities. This action, commonly known as “inspiration porn,” is one of the most offensive barriers that the Disability Community faces. The objectification of disabled people for the benefit of the non-disabled community is damaging to people on each side of the equation. It diminishes the non-disabled community’s ability to see past an individual’s diagnosis and understand that disability is not a catastrophe. It also limits opportunities for disabled people to be taken seriously and to be acknowledged for their actual achievements–not for “simply getting out of bed and remembering their names every morning” as the late Stella Young, an Australian comedian, journalist, disability rights activist and educator, remarks in her TEDxSydney presentation (TED.com, 2014).

In her 2021 article “4 Examples of Inspiration Porn,” Kayla Kingston provides three points to consider when encountering stories about people with disabilities:

- Ask yourself who the intended audience of the story is. Is the story meant to help nondisabled people feel good about themselves, or is it being told to amplify the voices of the disabled?

- Think before you share on social media. How would a person with a disability view this post?

- And, in the meantime, be sure to follow and share stories from disabled people themselves.

There are many people with disabilities who are very inspirational and who deserve recognition for their achievements. Aaron Fotheringham, an extreme wheelchair athlete who performs tricks adapted from skateboarding and BMX; Temple Grandin, a scientist and author with Autism; and Frida Kahlo, a Mexican artist who survived both polio and a bus accident that crushed her pelvis and caused chronic pain after her body healed, inspire people because of their contributions to society, not because they are disabled.

Figure 10.5 Being an “ally” includes these four principles.

10.3.11 Working and learning alongside people with disabilities

Given the prevalence of disabilities, it is possible that you, your classmates and/or your work colleagues are part of the Disability Community. Disabled people are not required to disclose their disabilities to anyone unless they need a modification of part or all of the work they are required to do. This can be related to the tasks required or to the way the work is done. These modifications are called disability-related reasonable accommodations and can be as simple as allowing the disabled person to have their desk near the restroom or providing a small refrigerator for the individual to use to store their insulin.

The accommodation process is an individualized, interactive process between the person requesting the accommodation and a company’s ADA Coordinator or a college or university’s DIsability Services Office. The Association on Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD), the national organization for post-secondary education accommodation professionals, has a detailed summary of the accommodation process at colleges and universities (Meyer, et al., 2012).

10.3.11.1 Animal Helpers

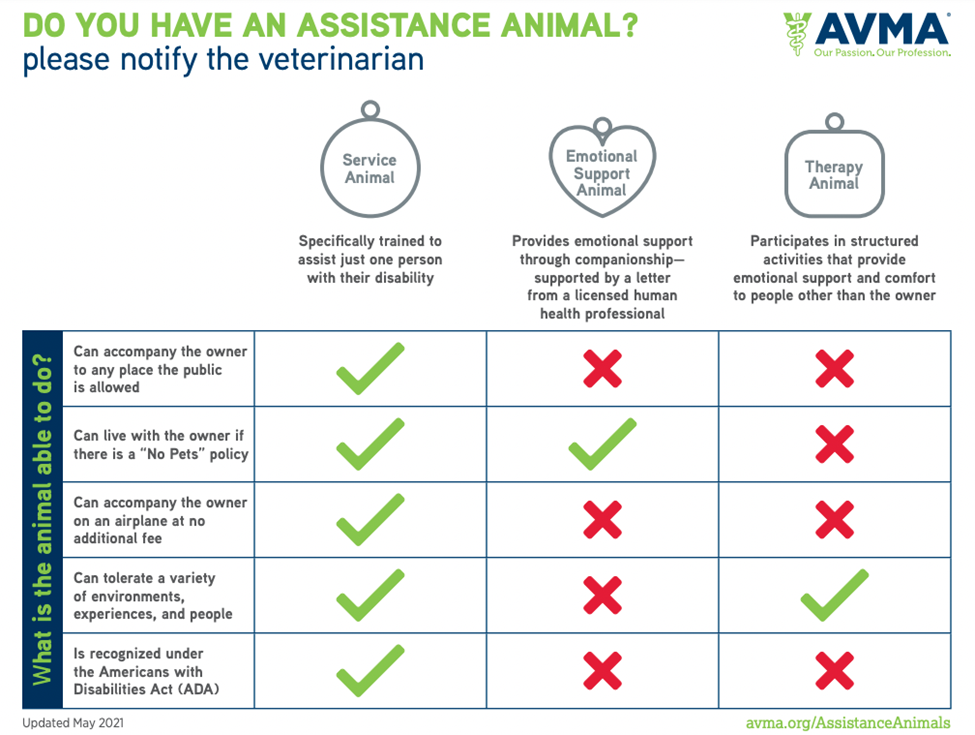

Many people with disabilities use assistance animals as part of their disability-related accommodations. Service animals are frequently confused with Emotional Support Animals (ESAs) and Therapy Animals, which can make the accommodation process a bit more complex at best, and at worst, can put the person with disabilities in danger or in a potentially deadly situation. This chart, Figure 10.X, created by the American Veterinary Medicine Association (2021), gives a summary of each role; more detailed discussion follows.

|

Assistance Animal Type |

Service Animal |

Emotional Support Animal |

Therapy Animal |

|

Job / Abilities |

Trained to assist a specific person with their disability. |

Provides emotional support through companionship. Requires a letter from a licensed human health professional. |

Participates in activities that provide emotional support and comfort to many people. |

|

Can go with the owner to any public place. |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Can live with the owner even in residences where no pets are allowed. |

YES |

YES |

NO |

|

Can go with the owner on an airplane at no additional charge. |

YES |

NO |

NO |

|

Tolerates many different settings, activities, and people. |

YES |

NO |

YES |

|

Is recognized by the Americans with Disabilities (ADA) Act. |

YES |

NO |

NO |

Figure 10.6. Abilities of different types of assistance animals.

10.3.11.1.1 Service Animals

The Americans with Disabilities Act regulations limit the definition of “Service Animal” to dogs and (with special provisions) miniature horses. The U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division (2022) has a comprehensive website dedicated to guidance on the ADA. To meet the requirements under the ADA (emphasis added):

Service animals are defined as dogs that are individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with disabilities. Examples of such work or tasks include guiding people who are blind, alerting people who are deaf, pulling a wheelchair, alerting and protecting a person who is having a seizure, reminding a person with mental illness to take prescribed medications, calming a person with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) during an anxiety attack, or performing other duties. Service animals are working animals, not pets. The work or task a dog has been trained to provide must be directly related to the person’s disability.

Some State and local laws define service animals more broadly than the ADA does. Information about such laws can be obtained from the relevant state attorney general’s office.

In addition to the provisions about service dogs, the Department’s ADA regulations have a provision about miniature horses that have been individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with disabilities.

There is no official registry for service animals, and no standard for identification of a service animal. There are many for-profit companies that sell “official” ID cards and vests to falsely “certify” an animal and incorrectly provide animal owners without disabilities assurance that the merchandise provides their pet with legal status as a service animal. This creates a dangerous situation for true service animals, who are often attacked or otherwise distracted by the “certified” pet. Nonetheless, most disabled people who rely on service animals do choose to use a special leash or vest to help dispel the questions about their animal as they move throughout the community.

Employers or members of a company’s staff may ask the disabled person two questions about the service animal:

- Is the dog a service animal required because of a disability?

- What work or task has the dog been trained to perform?

The service animal handler must be able to fully answer both questions if asked. It is illegal to ask about the person’s disability, require medical documentation, require a special identification card or training documentation for the dog, or ask that the dog demonstrate its ability to perform the work or task.

When you encounter a service dog, do not try to pet it or get its attention. Doing so will prevent it from doing its job, which often is lifesaving to the person it is teamed with. If a service dog approaches you without a human teammate, the dog is trying to bring help to its human partner, who is likely to need emergency medical attention. Do not pick up the leash, but follow the dog to where the disabled person is, alert any staff in the area who can help, and call 911 if needed.

10.3.11.1.2 Emotional Support Animals (ESAs)

Emotional Support Animals are not legally considered working animals. They can be any type of animal that is capable of providing comfort, a calming presence, and company for people with mental health-related disabilities (US DOJ, 2022).They are not permitted in the places service animals are, but do qualify for “no-pet” housing if the disabled person has a letter from a licensed healthcare professional.

10.3.11.1.3 Therapy Animals

Unlike Service Animals and Emotional Support Animals, Therapy Animals are specially trained to provide therapeutic enrichment to a large number of people, not to a specific person with disabilities. They are used in addition to medical and psychological treatment and often are seen in hospitals and other institutions. They generally have completed a lengthy and specific training program and often have formal certification from an animal-assisted intervention organization.

Therapy animals have no legal standing in the community. They must be invited by the management of a facility where animals are generally not allowed. Similar to other assistance animals, there is no required identification for therapy animals, but handlers often use bandanas, tags or vests to identify them when they are “on duty” in their community.

10.3.12 Summary of Working with People with Disabilities

Disability is a common human experience, with causes, symptoms and limitations that vary wildly from person to person. Human Services professionals–whether in training or in practice–must be knowledgeable about the medical and/or psychological impacts disabilities pose to their clients, as well as what protections their disabled clients are entitled to by state and federal law. While it is impossible for anyone to know everything about every disability, successful Human Services professionals will develop and maintain a network of people and programs in their communities who can become service partners and resources for their clients. Disability-related research will continue to generate new information and treatment options, but disability will never be fully preventable. With patience, persistence and curiosity, Human Services professionals will continue to be essential resources for people with disabilities and their families.

10.3.12.1 Want to know more about working with people with disabilities?

- Josh Blue “Being Disabled Has Its Perks” DryBar video https://youtu.be/kqs18nd0qgk

- Crip Camp documentary https://youtu.be/OFS8SpwioZ4

- KC Davis “How To Do Laundry When You Are Depressed” TEDxMileHigh https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1O_MjMRkPg

- If you’d like to know more about how to communicate with a deaf person if you don’t know sign language, watch How To Communicate With Deaf People Without Sign Language ┃ ASL Stew

- To understand more about inspiration porn, watch Stella Young’s Ted Talk, “I am not your inspiration, thank you very much.”

10.3.13 References

American Veterinary Medical Association. (2021, May). Do You Have An Assistance Animal? (Clinic Poster). Service, emotional support, and therapy animals. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.avma.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/assistance-animals-in-clinic-poster-v2-2021.pdf

America’s Got Talent. (2021). Josh Blue Makes The Judges Laugh With Hilarious Stand-Up Comedy – America’s Got Talent 2021. YouTube. Retrieved December 12, 2022, from https://youtu.be/4pKQad4NiQY. Content cited is found from 6:39-7:50

Borenstein, J. (Ed.). (2020, August). Stigma, prejudice and discrimination against people with mental illness. Psychiatry.org – Stigma, Prejudice and Discrimination Against People with Mental Illness. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/stigma-and-discrimination

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, July 26). Become a disability A.L.L.Y. in your community and improve inclusion for all. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/humandevelopment/become-a-disability-ALLY.html?s_cid%3Dncbddd_dhdd_ALLY_social_2021-06&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1670798666459353&usg=AOvVaw3NXGI4E_sCpCfNFYnaMD6C

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Penguin.

Inoue, C., Shawler E;, E., Jackson, C. H., & Jackson, C. A. (n.d.). Veteran and military mental health issues. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34283458/

Kingston, K. (2021, September 15). 4 Examples of Inspiration Porn. Think Inclusive, the Blog of MCIE. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://www.thinkinclusive.us/post/4-examples-of-inspiration-porn

Ladau, E. (2021). Demystifying disability: What to know, what to say, and how to be an ally. Ten Speed Press.

Meyer, A., Thornton, M., & Funckes, C. (2012). The professional’s guide to exploring and facilitating access. AHEAD. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.ahead.org/professional-resources/accommodations/documentation/professional-resources-accommodations-professional-guide-access

Munyi , C. W. (2012, April 24). Past and Present Perceptions Towards Disability: A Historical Perspective . Disability Studies Quarterly. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://dsq-sds.org/article/download/3197/3068

NowThis News. (2020). Commemorating 30 Years of the Americans with Disabilities Act . YouTube. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQafuiLGP7g&t=64s

Queremel Milani, D. A., & Tadi, P. (2022, January). Genetics, chromosome abnormalities – statpearls – NCBI bookshelf. National Institutes of Health–National Library of Medicine. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557691/

Random House, Inc. (2022). Diagnosis definition & meaning. Dictionary.com. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/diagnosis

Random House, Inc. (2022). Disability definition & meaning. Dictionary.com. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/disability

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2021). Living With Disabilities. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2021/comm/living-with-disabilities.html. Data based on 2019 American Community Survey, 1-year estimates,

U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. (2022, December 7). ADA Requirements: Service Animals. ADA.gov. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.ada.gov/resources/service-animals-2010-requirements/#miniature-horses

U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. (2022, December 7). Frequently asked questions about service animals and the ADA. ADA.gov. Retrieved December 11, 2022, from https://www.ada.gov/resources/service-animals-faqs/

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Genetic disorders. MedlinePlus. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://medlineplus.gov/geneticdisorders.html

University of Texas at Austin College of Education. (2022, November 10). The Deaf Community: An introduction. National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes. Retrieved December 4, 2022, from https://nationaldeafcenter.org/resource-items/deaf-community-introduction/

Varadaraj, V., Deal, J., Campanile, J., Reed, N. S., & Swenor, B. K. (2021, October 21). National prevalence of disability and disability types among adults in the US, 2019. JAMA Network Open. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2785329.

Vice. (2018). How to Treat a Person with Disabilities, According to People with Disabilities. YouTube. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W6c6JLbczC8.

Young, S. (2014). I’m not your inspiration, thank you very much. TEDxSydney. TED.com. Retrieved December 4, 2022, from https://www.ted.com/talks/stella_young_i_m_not_your_inspiration_thank_you_very_much?language=en.

10.3.14 Licenses and Attributions for Working with People with Disabilities

10.3.14.1 Open Content, Original

“Working with People with Disabilities” by Sheila R. Hoover is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.1. “Types of Stigma” by Sheila R. Hoover is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Disability etiquette activity” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.6. “Abilities of Different Types of Assistance Animals.” Data from “Do You Have an Assistance Animal?” by AVMA.

10.3.14.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 10.4. “Living with Disabilities” by the U.S. Census Bureau is in the public domain.

Figure 10.5. “Being an Ally” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

10.3.14.3 All Rights Reserved

Figure 10.2. “Commemorating 30 Years of the Americans with Disabilities Act” by NowThisNews is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.3. “Conversations with Ivanova: People First and Identity First Language by Informing Families” is under the Standard YouTube License.