11.4 Working with Military Service Members and Veterans

Some human services practitioners choose to work specifically with military service members or veterans. They may have been in the military themselves. Other practitioners will encounter service members and veterans in other settings such as counseling centers, houseless shelters, or in government agencies. In any case, it is helpful to know what motivates someone to become a member of the military.

Individuals have a wide range of reasons for enlisting in the military, from patriotism and family tradition to the benefits of training and the culture (Hall, 2011). One of the primary reasons is the family tradition (Hall, 2011). After generations of military service, it often becomes important for some individuals to continue to serve one’s country in a meaningful way (Hall, 2011). One might even consider proudly wearing the uniform again and show support for our troops by proudly wearing it on the 4th of July (Hall, 2011). On the other hand, some service members decide to join because they have become accustomed to the military life going up as children, and the military structure is a normal and familiar place (Hall, 2011). Some service members might choose to enlist for several other reasons, such as the benefits that come with enlistments like the sign-on bonus, a steady income, and educational benefits like having their schooling paid for and learning to specialize in a military occupation (Hall, 2011).

On the other hand, some individuals join military life as an escape from their current situations in their life, such as growing up in an environment that is not safe, struggling with addictions, or struggling with a gang mentality (Hall, 2011). For example, when someone has had a difficult start in life, such as many individuals going through rough times when they are growing up, they may choose to join the military to escape their former lives. In return, they seek to set themselves up for a better future (Hall, 2011). Finally, some people enlist in the military because they want to psychologically identify themselves as warriors (Hall, 2011). This psychological concept comes with the ideals that one is achieving a rite of passage (Hall, 2011). This is often seen as a form of growth and maturity – a way to mark your transition into adulthood (Hall, 2011).’’

11.4.1 Who are our Military Service Members?

The demographics of the modern active-duty military force have significantly changed over the past 50 years. The percentage of minorities serving in the active-duty military has increased exponentially and has been matched with an increase in racially diverse officers. Not only are more women serving, but they are also attaining positions of leadership at a much higher rate than in previous generations.

According to the Pew Research Center, the number of military persons on active duty has been decreasing over the past few decades, from 1.6 million in 1988 to 1.34 million in 2017. Women are now well-represented in the U.S military and are likely to comprise about 16% of active-duty personnel, up from 9% in 1980 and just 1% in 1970. In addition, the percentage of female officers has steadily increased over the last 40 years. In 1975, 5% of officer commission holders were women; by 2017, this share had risen to 18%(Barroso, 2019)

A more recent look at the racial and ethnic profile of current active-duty service members depicts an above-average number of non-Hispanic whites and black and Hispanic adults. Moreover, the share of these people has been steadily increasing. In 2017, the United States Armed Forces had 57% white members, 16% black members, 16% Hispanic members, and only 4% Asians. An additional 6% belonged to “other” or unknown ethnicity. Hispanics are the fastest-growing minority population in the military, which corresponds with a general trend in American demographics (Barroso, 2019)

Figure 11.14. The changing profile of the U.S. military: Smaller in size, more diverse and more women in leadership.

11.4.2 What is “Active Duty”?

According to the United States Census Bureau, “Active duty military service includes full-time service, other than active duty for training, as a member of the U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, U.S. Air Force, U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Coast Guard or as a commissioned officer of the Public Health Service or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or its predecessors, the Coast and Geodetic Survey or Environmental Science Service Administration. Active duty also applies to a person who is a cadet attending one of the five United States Military Service Academies (United States Census Bureau, 2021).

Active duty applies to service in the military Reserves or National Guard only if the person has been called up for active duty, mobilized, or deployed. Service as a civilian employee or civilian volunteer for the Red Cross, USO, Public Health Service, or War or Defense Department are not considered active duty. For Merchant Marine service, only service during World War II is considered active duty, and no other period of service”(United States Census Bureau, 2021).

11.4.3 Who are our Veterans?

Throughout history, there have been many brave Americans that have served our country. The Green Mountain Boys, the Buffalo Soldiers, Tuskegee Airman, Women Airforce Service Pilots, Screaming Eagles, and Green Berets are all examples of some of these courageous people. Veterans are the men and women who have served their country honorably at home and abroad, at sea, on land and air—and since 1973, many have bravely served as an all-volunteer force. These brave individuals represent the very best of our nation’s character, commitment to service, and willingness to sacrifice. Let’s start with definitions.

11.4.3.1 What is a Veteran?

According to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) “Title 38 of the Code of Federal Regulations defines a veteran as a person who served in the active military, naval, or air service and who was discharged or released under conditions other than dishonorable (Veterans Authority, 2017).”

According to the United States Census Bureau, Veterans are men and women who served in the U.S. army, air force, marine corps, navy or coast guard but are not currently active. Moreover, Veterans may be individuals who have served in the Merchant Marine during World War II. Additionally, individuals who have served in the National Guard or Reserves are considered veterans only if they have ever been called up for active duty, not counting the 4-6 summer training camps.

11.4.3.2 The Changing Demographics of Veterans

According to the United States Census Bureau American Community Survey Report that analyzed the roughly 18 million American veterans, or 7% of the adult population in the United States, who were active members of the nations U.S. Armed Forces in 2018, ranging from 18 to over 100 years old who have served in military conflicts as diverse as the Korean War and the Global War on Terrorism.(Vespa, 2020).

The number of veterans in the U.S. has declined by a third over the past two decades, from 26.4 million in 2000 to 18.0 million in 2018; there are currently approximately 500,000 World War II veterans living today, which is down from 5.7 million just 20 years ago (Vespa, 2020).

The median age of a veteran in the United States today is about 65 years (Vespa, 2020). Post-9/11 veterans are the youngest group of Americans to return from war, with a median age of about 37 (Vespa, 2020). The median age of Vietnam Era veterans is 71(Vespa, 2020). World War II veterans are the oldest group in America, with a median age of 93(Vespa, 2020). This group is followed by Vietnam-era vets, who are about 73 years old (Vespa, 2020).

It has been found that veterans from more recent service periods are the most educated (Vespa, 2020). For example, more than three-quarters of Post 9/11 and Gulf War veterans have at least some college experience, with over one-third of Gulf War veterans having obtained a college degree (Vespa, 2020).

Post-911 veterans have a 43% chance of having a service-connected disability, which is significantly higher than the chance for veterans in another era (Vespa, 2020). Additionally, compared to any other period, post-9/11 veterans with a service-connected disability had a 39 percent chance of having one or more disability ratings of 70 percent (Vespa, 2020).

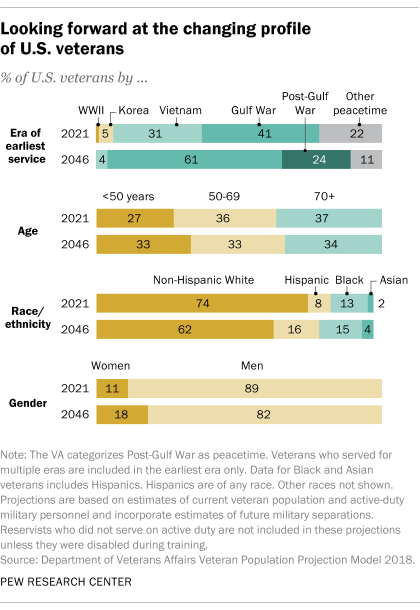

According to the Pew Research Center, the demographic profile of veterans is expected to continue to change dramatically in the next quarter century (Schaeffer, 2021). Currently, only 11% of the total Veteran population in the United States are women (Schaeffer, 2021). This number is expected to rise by 18% by 2046. In 2016, there were an estimated nine million veterans in the U.S., and 89% of them were men (Schaeffer, 2021). The number of male veterans is on the decline, with projections that it will decrease from approximately 17 million in 2021 to about 10.3 million in 2046 (Schaeffer, 2021).

As trends show that the U.S. population is steadily becoming more diverse, this is also expected to be true of the veteran population(Schaeffer, 2021). Between 2021 and 2046, the number of veterans who are non-Hispanic White is expected to decrease from 74% to 62%(Schaeffer, 2021) as shown in figure 10.X. Hispanic veterans are predicted to make up 16% of the veteran population, up from 8%, and Black veterans will represent 15%, up from 13% (Schaeffer, 2021).

“Figure 11.15. Looking forward to the changing profile of the U.S. Veterans” by Pew Research Center is in the public domain (Schaeffer, 2021)

11.4.3.3 Veterans with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Queer Identities

In 1993, a policy named “don’t ask, don’t tell” went into effect, allowing people that identify as LGBTQ+ to serve in the military. Under this policy, service members would not be asked about their sexual orientation during the recruitment process but would be discharged if they disclosed it. In 2011, Congress repealed the policy openly gay, lesbian, and bisexual people in the military were permitted to serve the United States Military. In 2021 the ban on transgender individuals serving in the Armed Forces was rescinded, opening the door for those who don’t identify with their biological gender to enlist and serve.

It is estimated that approximately 1 million gay and lesbian Americans are Veterans (2.8%). Among those, an estimated 65,000 people identify as gay or lesbian and are currently serving in the military. The representation of women LGBT veterans is significantly higher than that of their male counterparts, with an estimated 2.9% of active-duty women who identify as lesbian/bisexual in comparison to 0.6% of active-duty men who identify as gay/bisexual. Women make up an estimated 15% of active-duty personnel. (Gates, 2010).

11.4.4 Settings for Veteran Services

It could easily be argued that as long as our nation is involved in conflicts, there will continue to be great efforts to ensure the people involved in those conflicts are taken care of when they return home. There are many available services for veterans, yet access can be challenging. Veteran services are largely area-specific and many veterans find themselves having to drive for several hours to access the care that they need. Reliable transportation and distance can be a barrier.

11.4.4.1 The Department of Veterans Affairs

This is the largest source of support for veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs is a federal agency within the United States government whose purpose is to fulfill President Lincoln’s promise “[t]o care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan” by serving and honoring the men and women who are America’s veterans” (United States Department of Veterans Affairs,2015).

This agency has the responsibility of assisting with millions of pensions, service-related disability claims, education benefits, life insurance claims, healthcare benefits, and much, much more. If you’ve been paying attention to the news over the past several years, it’s no surprise to hear they are struggling to meet the ever-growing needs of service members and veterans. Regardless, the VA is the primary service provider for veterans. There are many roles for human services providers within the Department of VA, such as resource and referral providers.

11.4.4.2 County VA offices and VSOs

Like the federal Department of Veterans Affairs, there are also County Veteran Affairs offices. While they are directly linked to the federal VA, they are funded by the local county and usually employ Veteran Service Officers (VSOs). These VSOs assist veterans in completing the rigorous paperwork involved in applying for benefits. And since they are typically locally funded, they likely have access or knowledge of local programs, grants, and services that are not directly administered by the VA.

11.4.4.3 Mental Health

In addition to Department of VA offices and County VA offices, many larger cities often have Community-Based Outpatient Clinics (CBOCs). Though these CBOCs are often primarily utilized to provide veteran health care, they are typically staffed by one or more Licensed Masters level Social Worker (LMSW), Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC), or Psychologists. Vet Centers are also available in select cities. Vet Centers are connected with the VA, but typically operate independently with the sole purpose of providing individual- and group-therapy to veterans in their identified catchment area or area of responsibility. For smaller communities that may not have a CBOC or Vet Center, the VA likely has an agreement or contract setup with a local private agency, though this is not always the case. It’s a safe bet that the smaller the city, the more likely a veteran will have to travel to get access to veteran-specific services. Human services practitioners who are certified or licensed in counseling will find opportunities here.

11.4.4.4 Veteran Suicide

One last section is necessary when talking about veterans and mental health struggles. Sadly, veteran suicide rates are high. According to a report posted in the Military Times, roughly twenty veterans commit suicide every day, and despite making up only 9% of the population, represent 18% of all American suicides.

11.4.5 Military Culture

Culture is shaped by the social environment and includes a shared sense of values, norms, ideas, symbols, and meanings (Redmond, Wilcox, Campbell, Kim, Finney, Barr, & Hassan, 2015). Military culture is a distinctive set of customs, practices, traditions, and ways of behavior that is widely known as an essential component in the organizational structure, framework, and guidelines (Redmond et al., 2015). The military strives to create a sense of uniformity by emphasizing core values that become an integral part of military culture, which is why service members share experiences and values, as well as languages and symbols (Redmond et al., 2015).

While all cultures integrate individuals, the military needs a strong, cohesive culture that allows it to function at optimal levels during times of crisis (Redmond et al., 2015). Some people voluntarily join the military and identify with the culture from the beginning, whereas others learn to adopt this identity during military socialization (Redmond et al., 2015). Another unifying aspect of military culture is the warrior mentality (Redmond et al., 2015).

This group of core values and ethos will be instilled in all U.S. armed forces members to make them strong, resilient, and competent professionals ready to face any challenge (Redmond et al., 2015). The warrior ethos is integral to what makes the military strong (Redmond et al., 2015). It emphasizes Mission first, staying in the fight no matter what, and never leaving one of our own behind (Redmond et al., 2015).

Military culture has a major impact on the lives of veterans who are re-integrating into society in numerous ways. It is important for those who have not served in the military to be familiar with some fundamentals of military service. The armed forces are a uniformed culture with defining characteristics. There are many terms that can be used to describe their culture. These components include camaraderie, pride, esprit de corps, tradition, and Mission.

11.4.5.1 Camaraderie

The deep bond between members in an organization, team, or family who depend on each other for their successes and failures resonates with people who have served in the military. Friendships that form among members in close-knit communities last for a lifetime.

Figure 11.16. In this TED talk entitled Why Veterans Miss War Sebastian Junger discusses the importance of camaraderie, how combat affects the brain and how both contribute to the experience of being in the military. Click here or on the image to view.

11.4.5.2 Pride and Esprit de Corps

Pride is meant to be a force that inspires faith in our allies and fear in our enemies. People in the military are driven to perform their jobs with the utmost care, professionalism, and excellence (Schumm, 2003, p.837). It also boosts a great deal of confidence and feelings of invincibility as group, esprit de corps.

11.4.5.3 Tradition

Soldiers, Marines, Airmen, or Seamen are usually organized together in various-sized groups called units and each of honor, pride, ability, and courage. For example, in the HBO series Band of Brothers, the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division was glorified for its courage, valor, and bravery during various operations of World War II.

11.4.5.4 The Mission

The last term is potentially the most important one, and potentially the most ambiguous. The mission is any task that a service member or group is focused on at any given moment. No matter how large, complex or small the task, the Mission of the United States military member refers to any task they are currently focused on at any given moment in time, and that task becomes part of their goal until their Mission is completed. Within the military, the Mission always comes first. The Mission is prioritized over hopes, dreams, health, and safety because it is a crucial part of the culture.

11.4.6 Challenges and Strengths

Military service members and veterans and their families have been shown to face some challenges once they transition from active service. It is common for these individuals to experience increased stress, anxiety, and depression levels which often lead to higher rates of alcoholism and substance abuse. Additionally, it can be difficult for these veterans to find employment or quality housing, potentially leading them towards houselessness (Van Slyke & Armstrong, 2019).

11.4.6.1 Systemic Challenges

According to Syracuse University Veterans and Families report (2019) military veterans often face a wide range of challenges after they return from service. And for those with loved ones who are seeking medical care or assistance, it can be particularly difficult. Even though more American private and public-sector organizations are engaging in assessing the needs of America’s veterans, few assessments exist that comprehensively analyze the major challenges that these brave veterans face (Van Slyke & Armstrong, 2019).

11.4.6.2 Family Impact

As service members return home from war and exit the military, some end up seeking help for psychological and physical injuries that may be related to their military service through the Veterans Administration (VA), Department of Defense (DoD) and community agencies (Glynn, 2013).

For military personnel, transitioning back to civilian life can be difficult. They are often faced with a number of challenges after leaving their career in the armed forces and their family and community can also struggle to understand the experience of military service. This can result in a number of different issues that have a negative impact on the mental health and well-being of these individuals(Doyle & Peterson, 2005). Many service members have noted that when a deployed family member returns home, families often try to pick up where they left off. However, such a change in family dynamics, as well as a shift in the tasks and responsibilities often causes a fair amount of stress on the family unit as a whole (Doyle & Peterson, 2005).

11.4.6.3 Reintegrating to the civilian workforce

Re-entry for military veterans who have served in conflict zones can be very challenging. According to Pew Research Center survey report that after the 9/11 attack, 76% of veterans who served in combat saw their military experience come in handy and find it helpful for get ahead, but 51% say they had some difficulties readjusting to civilian life. It has been found that the majority of these combat veterans suffer from strained family relations and experience some form of outbursts of anger or irritability. Fully half (49%) of those surveyed report that they have likely suffered from post-traumatic stress. Despite expressing a deep sense of pride in their service and an increased appreciation for life many service members question whether the government has done enough to support them. Veterans returning home often face challenges due to the things they experienced in combat. After the September 11th terrorist attacks, 52% of all post-9/11 combat veterans said that they had experienced at least one experience that was emotionally distressing. Noncombat veterans are often less likely to report having such experiences, but they are not immune from distress (Pew Research Center, 2011)

11.4.6.4 Discharged

According to the Public Health Research, Practice and Policy (2018) Veterans who are discharged from military service due to misconduct are vulnerable to a variety of negative health-related outcomes, including houselessness, incarceration, and suicide. Discharged veterans who have had misconduct in the military are more likely to experience chronic health conditions such as chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, and AIDS/HIV. These are often factors of behavioral nature including substance abuse or mental illness. These risks relate to the unique mental and behavioral health problems that are more prevalent in this population. Poor decision making can be caused by chronic health conditions and other mental health needs that are unmet or unrecognized. Specifically, misconduct may occur as a result of poor functioning and decision making while in service, sometimes caused by unmet or unrecognized chronic health conditions and other mental health needs (Brignone, Fargo, Blais, & Gundlapalli, 2018) .

11.4.6.5 Houselessness

Houselessness is an issue for many veterans (Fargo et al., 2011). Evidence has consistently indicated prevalence among veterans and non-veterans alike, with both groups showing high levels of mental illness, extreme poverty as well as substance abuse. (Balshem et al., 2011; Tsai & Rosenheck, 2015).Combat experience and trauma such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been shown to have a modest link to Veterans becoming at risk for houselessness. (Metraux, Clegg, Daigh, Culhane, & Kane, 2013; Rosenheck & Fontana, 1994). Younger veterans have experienced significantly higher unemployment and poverty rates than veterans from previous service eras (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016; National Center for Veterans Analysis & Statistics, 2015). “Houselessness among these women as part of a larger “web of vulnerability” where the five predominant roots of houselessness were 1) childhood adversity; 2) trauma and/or substance abuse during military service; 3)post military abuse, adversity, and relationship termination; 4) post-military mental health, substance abuse, and/or medical problems; and5) unemployment”. (Hamilton et al., 2011, p. S207)

11.4.6.6 Strengths

According to the National Center for Post Traumatic Disorder Veterans Employment Handout, all members of the military have specialized training designed to “break an individual down” and then train them back up. Basic Such training varies by branch but includes intense physical and academic training, as well as socialization into the culture of that branch. The training that you provide to vets and members of the military is built on a foundation made of combat, training, and leadership skills that they have already learned while serving. Military service teaches strong values, selfless service, and loyalty. These are admirable attributes of a worker.

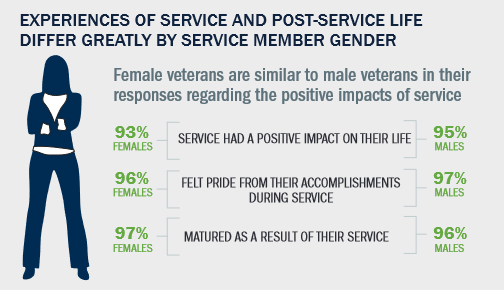

Military service does not just result in a number of skills, training, and experiences that would be beneficial to any company or agency; it also results in the acquisition of leadership skills, specialized training in weaponry and hand-to-hand combat, and experience with working as a member of a team. Military service teaches and cultivates leadership skills and many veterans feel positive about their experience as shown in figure 11.17. Service members learn to take responsibility for self and actions, make sound and timely decisions, set an example, and understand and accomplish assigned tasks. Moreover, be dependable, cultivate abilities to meet a variety of challenges, and be disciplined.

Figure 11.17. “Experiences of Service and Post-Service Life By Service Member Gender” shows the positive feelings that many have about their military experience.

Military service members afford individuals access to education and training, resulting in technical and tactical proficiency in a variety of skills and technical education for a specific military occupational specialty. Military service helps promote personal growth and positive emotional experiences, such as enhanced maturity, self-improvement, strengthening of resiliency, and positive transformations following trauma or situations of extreme stress. Military service enhances interpersonal skills and relationships, such as creating camaraderie and deep friendships, working together in teams and understanding the importance of cooperation, and looking out for the welfare of the team.

Applying an intersectionality framework to Military members and Veteran communities is important because it allows examining how the intersectional identities of veterans are shaped by their military experiences (Henry, 2017). Unfortunately, intersectionality has a very limited scope in military and veteran literature (Henry, 2017).

11.4.7 Summary of Working with Military Service Members and Veterans

Human services professionals who work within the VA follow a mission statement that maximizes health and well-being of all military members, families, and communities. The vision includes leading by example, setting high standards, and establishing innovative psychosocial care and treatment.

“The values established by the VA and UCMJ suggest, that all social workers who serve military members, veterans, military communities, and their families must advocate for optimal health care by respecting the dignity and worth of the individual, understanding military socio-cultural environments, empower veteran’s as the primary member of their PACT, respect the individual role and expertise of the veteran, focus on the needs of at-risk-population within military communities/families, promote learning (fostering knowledge, enhances clinical social work practice, advances leadership, and focuses on administrative excellence), exemplifies and models professional and ethical practice, and promotes conscientious stewardship amongst organizational member(s) and within community services” (VA, 2014).

Today, human services practitioners, counselors social workers working in the VA have evolved into a professional service responsible for the treatment of military members, military communities, and family members. These responsibilities include but are not limited to treatment approaches which address individual social problems, acute/chronic conditions, terminal patients, and bereavement.

Populations of veterans needing services are: houseless, the aged, HIV/AIDS patients, spinal cord injury, Ex-Prisoners Of War, Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans, Vietnam and Persian Gulf Veterans, WWI and WWII Veterans, Korean War Veterans, Active/Inactive/Reserve/National Guard members, and their families.

Helping practitioners help coordinate program such as:

- Community Residential Care (CRC)

- Financial or housing assistance

- Getting help from such agencies as Meals on Wheels

- Applying for benefits (health care, vision, optical, mental health, dental, financial, educational, and more)

- Arranging for respite care, or moves such as into assisted living

- Family, bereavement, PTSD and other counseling

- Substance Use Disorder prevention or treatment

- Abuse, mistreatment, being taken advantage of, maltreatment, or need of a guardianship

- Parents or spouses needing help with child car or health concerns

- Need direction of services or other unspecified needs

Be aware that some veterans will be most comfortable speaking with another veteran about their time in the service. Especially if you have not served yourself, approach the veteran with awareness of this; let them lead the way when speaking about military service.

Social workers and other helping professionals help with assessment, crisis intervention, high-risk screening, discharge planning, case management, advocacy, education, and psychotherapy. The VA social workers motto: “If you have a problem or a question, you can ask a social worker. We’re here to help you!” (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017). There are many roles for human services professionals to play when it comes to working with military service members and veterans.

11.4.8 References

Balshem, H., Christensen, V., Tuepker, A., & Kansagara, D. (2011). A critical review of the literature regarding houselessness among veterans.

Barroso, A. (2019, September 10). The changing profile of the U.S. military: Smaller in size, more diverse, more women in leadership. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/10/the-changing-profile-of-the-u-s-military/

Boyer, K. (2018). Effective Social Work Practice with Military, Veterans, and their Families.

Brignone, E., Fargo, J. D., Blais, R. K., & Gundlapalli, A. V. (2018). Peer Reviewed: Chronic Health Conditions Among US Veterans Discharged From Military Service for Misconduct. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). Employment situation of veterans: 2015. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/vet.pdf

Bureau, U. C. (2021). Veterans Glossary. https://www.census.gov/topics/population/veterans/about/glossary.html

Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PSTD. (2012). Positive Outcomes of Military Service. https://www.va.gov/vetsinworkplace/docs/em_positiveChanges.html

Fargo, J., Metraux, S., Byrne, T., Munley, E., Montgomery, A. E., Jones, H., … & Culhane, D. (2012). Prevalence and risk of houselessness among US veterans. Preventing chronic disease, 9.

Fawcett, E. (2021, March 19). LGBTQ in the Military • Military OneSource. Military OneSource. https://www.militaryonesource.mil/military-life-cycle/friends-extended-family/lgbtq-in-the-military/

Gates, G. (2010). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual men and women in the US military: Updated estimates.

Hall, L. K. (2012). The importance of understanding military culture. In Advances in social work practice with the military (pp. 3-17). Routledge.

Henry, M. (2017). Problematizing military masculinity, intersectionality and male vulnerability in feminist critical military studies. Critical Military Studies, 3(2), 182–199. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23337486.2017.1325140

Hamilton, A. B., Poza, I., & Washington, D. L. (2011). “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: Pathways to houselessness among women veterans. Women’s Health Issues, 21(4), S203-S209.

Junger, S. (2014, May 23). Why veterans miss war [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGZMSmcuiXM

Maury, R.V.; Zoli, C., Fay, D.; Armstrong, N.; Boldon, N.Y.; Linsner, R. K; Cantor, G.(2018, March). Women in the Military: From Service to Civilian Life. Syracuse,NY: Institute for Veterans and Military Families, Syracuse University.

Metraux, S., Clegg, L. X., Daigh, J. D., Culhane, D. P., & Kane, V. (2013). Risk factors for becoming houseless among a cohort of veterans who served in the era of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. American Journal of Public Health, 103(S2), S255-S261.

Metraux, S., Cusack, M., Byrne, T. H., Hunt-Johnson, N., & True, G. (2017). Pathways into houselessness among post-9/11-era veterans. Psychological services, 14(2), 229.

National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. (2015). Veteran poverty trends. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/veteran_poverty_trends.pdf

Pew Research Center. (2011). Chapter 4: Re-Entry to Civilian Life. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/10/05/chapter-4-re-entry-to-civilian-life/

Pew Research Center. (2011). War and Sacrifice in the Post-9/11 Era. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/10/05/war-and-sacrifice-in-the-post-911-era/

Redmond, S. A., Wilcox, S. L., Campbell, S., Kim, A., Finney, K., Barr, K., & Hassan, A. M. (2015). A brief introduction to the military workplace culture. Work, 50(1), 9-20.

Richard, B. M. and T., & Work, F. S. U. D. of S. (2020). Service Members. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/humanservices/chapter/service-members-and-social-work/

Schaeffer, K. (2021). The changing face of America’s veteran population. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/05/the-changing-face-of-americas-veteran-population/

Schumm, W. R., Gade, P. A., & Bell, D. B. (2003). Dimensionality of military professional values items: An exploratory factor analysis of data from the Spring 1996 Sample Survey of Military Personnel. Psychological Reports, 92(3), 831-841.

Sion, L. (2016). Ethnic minorities and brothers in arms: competition and homophily in the military. Ethnic & Racial Studies, 39(14), 2489-2507. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1160138

Tsai, J., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2015). Risk factors for houselessness among US veterans. Epidemiologic reviews, 37(1), 177-195.

United States Department of Veteran Affairs. (2017, July 24). What VA social workers do. Retrieved from https://www.socialwork.va.gov/socialworkers.asp

Van Slyke, R., & Armstrong, N. (2019). Communities Serve: Highlights for State Government Officials.

Vespa, J. E. (2020). Those who served: America’s veterans from World War II to the War on Terror. World War II (December 1941 to December 1946), 485(463), 22.

Veterans Authority. (2017). What is a veteran? The legal definition. Retrieved from http://va.org/what-is-a-veteran-the-legal-definition/

11.4.9 Licenses and Attributions for Summary of Working with Military Service Members and Veterans

11.4.9.1 Open Content, Shared Previously

“Working with Military Service Members and Veterans” by Rebeca Petean is adapted from Effective Social Work Practice with Military, Veterans, and their Families by Katherine Boye and is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Adaptations include editing for brevity and clarity and remixing of the passages.

Figure 11.16. “Sebastian Junger: Why veterans miss war” by TED is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 11.17. Women in the Military: From Service to Civilian Life-Infographic by Institute for Veterans and Military Families and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptation: Cropping of the image only from infographic.

“What is Active Duty?” by Rebeca Petean is adapted from “Service Members” by Brian Majszak and Troy Richard in Introduction to Human Services is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: Updated.

“Veterans with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Queen Identities” by Rebeca Petean is an adaptation of LGBTQ in the Military: A Brief History, Current Policies and Safety by Military OneSource and Veterans with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Queer Identities by VA.gov. and is in the public domain. Adaptations include editing for brevity and clarity.

“Who are our Veterans?” by Rebeca Petean is adapted from Those Who Served: America’s Veterans From World War II to the War on Terror by U.S. Census Bureau and is in the public domain. Adaptations include editing for brevity and clarity and citing of the passages.

“Settings for Veteran Services” by Rebeca Petean is adapted from “Service Members” by Brian Majszak and Troy Richard in Introduction to Human Services is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: Edited for brevity and clarity; contextualized for human services.

“Military Culture” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “Service Members” by Brian Majszak and Troy Richard in Introduction to Human Services is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: edited for brevity and clarity.

“Challenges and Strengths” by Rebeca Petean is adapted from Communities Serve: Highlights for Local and Government Officials by Institute for Veterans and Military Families, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0, from Effective Social Work Practice with Military, Veterans, and their Families by Katherine Boye, which is licensed under CC BY 3.0, from Pathways Into Homelessness Among Post-9/11-Era Veterans by Metraux, Cusack, Byrne, Hunt-Johnson, and True, which is liecnsed under CC BY 4.0, and from National Center for PSTD by Department of Veterans Affairs, which is in the public domain. Adaptations include rewriting and remixing and citing of the passages.

“Working with Military Service Members and Veterans” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “Service Members” by Brian Majszak and Troy Richard in Introduction to Human Services, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: edited for brevity and clarity; contextualized for human services.

11.4.9.2 Open Content, Original

All sections not identified above are original content by Rebeca Petean and licensed under CC BY 4.0

11.4.9.3 All Rights Reserved

Figure 11.14. “Demographic shifts in today’s military show growing representation of racial and ethnic minorities” from “The Changing profile of the U.S. military: Smaller in size, more diverse, more women in leadership” (2021) Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. is all rights reserved and used with permission.

Figure 11.15. “Looking forward at the changing profile of U.S. veterans” from “The Changing profile of the U.S. military: Smaller in size, more diverse, more women in leadership” (2021) Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. is