4.9 Social Insurance Programs

Social insurance programs differ from social welfare programs in that they take into account any contributions that the beneficiary has made to the program. These programs may be considered more preventative in nature than the social welfare programs.

4.9.1 Social Security Disability Insurance

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) covers individuals who have worked enough years to qualify for Social Security payments if they become disabled with a condition that “is expected to last at least one year or result in death” (Social Security Administration, 2014, p. 4). Since this is not a public assistance program, applicants do not need to pass a means test. Benefits can also extend to some family members. After receiving SSDI benefits for two years, one automatically becomes eligible for Medicaid benefits as well. (Social Security Administration, 2014).

4.9.2 Medicare

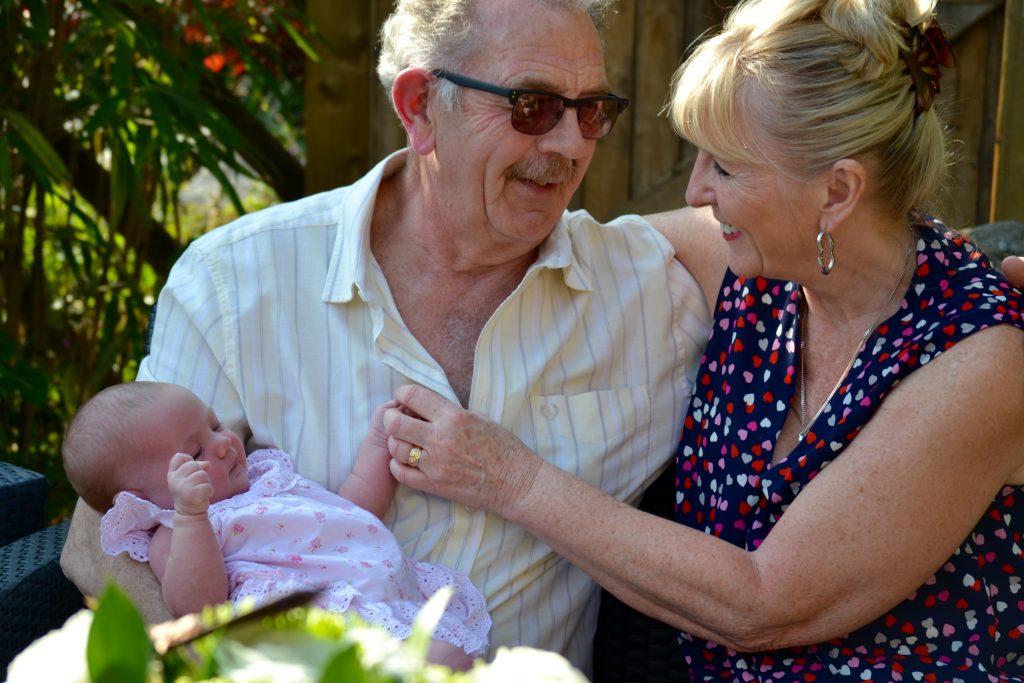

Medicare is a program, funded by tax revenues, which provides financial assistance for medical care for the nation’s elderly, retired, and some people with disabilities as shown in figure 4.21. Much more complex than Medicaid, Medicare’s benefits come in various forms (Part A, Part B, Part C, Part D). Part A (inpatient hospital coverage) is free, with the remaining optional components requiring the payment of a premium. Medicare is addressed in greater depth in Chapter 8.

Figure 4.21. Medicare and Social Security are both programs which benefit older Americans, along with other groups of people.

4.9.3 Social Security

Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) is the formal name for the program we more typically call Social Security. It provides an income to “qualified retired and disabled workers and their dependents and to survivors of insured workers” (Social Security Administration, 2011). Over 50 million Americans receive benefits, including over 85% of those aged 65 or older (Social Security Administration, 2011). Although it was never designed to be the primary source of income for the elderly, it is at least 90% of the income for 22% of married couples and 43% of other individuals 65 or older (Social Security Administration, 2011).

There is some concern about the long-term viability of Social Security due to the increasing average age and life expectancy of Americans, coupled with the trend of companies encouraging older workers to go into early retirement (Baker & Weisbrot, 1999). Some people will see little return on their Social Security tax payments, while others will draw much more out of the system than they put into it. The maximum monthly benefit payable to a retired worker in 2021 is $3,148, but they can only collect that much if they have earned $142,800 or more each year over a 35-year working career. The average retiree’s monthly Social Security payment in 2021 was $1,543/month (Brandon, 2021). Social Security will be discussed more in depth in Chapter 7.

4.9.4 Unemployment Insurance

Unemployment Insurance (UI) is aimed at preventing recently unemployed workers from slipping into economic despair while they search for a new job. There is no means test, and benefits paid out are based on earnings from one’s previous job. The program is funded by tax paid by employers rather than employees (Conrad, 2008). Workers can generally apply only if they’ve been laid off, but in some cases people who have been fired are eligible (Kirst-Ashman, 2013). In order to continue to receive benefits, one must also be actively looking for work and be able to furnish proof of that fact (Stone & Chen, 2014).

Each state runs its UI program quite differently. Payment levels are determined by how much the worker earned while working and what the average income is in that state, and benefits are often capped at around half the worker’s previous earnings (Levitan et al., 1998). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government also provided additional payments beyond state unemployment payouts, adding $300 per week for many people in need (Guerin, 2021).

4.9.5 Workers’ Compensation

Like UI, Worker’s Compensation is meant to help people stay out of poverty during temporary loss of income—in this case, due to an injury or disease sustained on the job. Workers’ Compensation is designed to cover lost wages, medical treatment for the condition, possible rehabilitation, and to compensate one’s family in the event of a workplace-related death (Levitan et al., 1998; Matthews, 2015). However, the total of an individual’s disability benefit payment (if any) and Worker’s Compensation payment cannot exceed more than 80% of his/her working income (Matthews, 2015).

4.9.6 Activity: Is the U.S. really a Meritocracy?

Earlier in the chapter, we asked you: could most of the hardworking people really be concentrated in the top 10%, or the top 1%? A meritocracy, which many believe the U.S. to be, would make this possible. Imagine this scenario, which illustrates vividly the relative lack of connection between hard work and economic success.

An educated white man “Mark” was laid off several years ago after over three decades as a mechanical engineer. He was in his mid-50s at the time, making over $100,000 a year, and had started working on his master’s degree in business administration (MBA). He continued to go to school after being laid off and finished that degree, all while struggling to find new work in his field. With multiple patents to his name, managerial experience, and decades of knowledge—plus now an advanced degree—one would think that it would be easy for him to find another job. Well, he did find a new job—assembling bicycles at a bike shop for a few months, before he left because of the shop owner’s racist views. Then he was a shelf stocker at a grocery store’s liquor section. Then he took a job as a school bus driver. Over those years, he put out dozens, perhaps hundreds of resumés, and scored many interviews, but never an offer that would put him back into engineering or management.

Why couldn’t he find a well-paying job? Why did he often have to settle for low-wage manual labor? Well, a lot of factors led to his predicament. His decades of experience and his advanced degree have, in some ways, made him more difficult to hire because he legitimately would have commanded a high salary. When he applied for jobs that paid less but for which he was overqualified, he would not get offers, perhaps because the employers were afraid he’d leave once he got something better. Some people in the industry even recommended he take his MBA off his resumé, so human resources managers didn’t see him as too expensive to hire.

Mark was a lot more fortunate than most since he had a well-paying career before his years of unemployment and underemployment. However, if the system favored those who got educated and worked hard, he would have had a lot more success in his job hunt. Though he has since become disabled, at age 64 now, he would have almost no chance of getting a job in his field since people will just see him as a soon-to-be retiree. It’s likely that many readers know people with similar stories in recent years.

4.9.6.1 Discussion Questions

- Does this illustrate that the US is or isn’t a meritocracy?

- Can you think of other examples that demonstrate whether or not the US is a meritocracy?

There are many factors that people cannot control that cause them to be unemployed, to file for bankruptcy, to apply for public assistance. It is our job as social workers to know that what our clients really need is not judgment—they need someone to recognize that they are people who have a story and deserve an opportunity to get on their feet, regroup, and keep fighting against a powerfully unequal system.

4.9.7 References

Baker, Dean and Weisbrot, Mark. Social Security: The Phony Crisis, https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo3632965.html

Biggs, A. G. (2011). Social Security: The story of its past and a vision for its future. AEI Press.

Guerin, L. (2021).Collecting Unemployment benefits in Hawaii. NOLO. https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/collecting-unemployment-benefits-hawaii.html.

Levitan, S. A., Mangum, G. L., & Mangum, S. L. (1998). Programs in aid of the poor (7th ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Matthews, J. (2015). Social Security, Medicare & government pensions: Get the most out of your retirement & medical benefits. Nolo.

Social Security Administration (2011). Social Security (Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance). http://www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2011/oasdi.pdf.

Social Security Administration (2014). Social Security Disability benefits. http://www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-05-10029.pdf.

4.9.8 Licenses and Attributions for Social Insurance Programs

4.9.8.1 Open Content, Shared Previously

“Social Insurance Programs” is adapted from “Poverty and Financial Assistance” by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, Social Work and Social Welfare and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce include light editing, vocabulary and context changes to adapt for the human services field.

Figure 4.21. This image is in the Public Domain.