5.5 Understanding and Working in Health-Care Settings

Human services practitioners will work with many clients who are also interacting with the health-care system. Whether or not you are working in a health-care setting, it is important to understand how health care and health insurance are organized in the United States. In addition, workers must understand that physical and mental health are interrelated although they have been socially constructed in the Western worldview as separate, with mental disorders being stigmatized. Often mental illnesses such as depression or anxiety have been seen as something that a person should and could “get over” as opposed to a physical ailment such as a sprained ankle or strep throat that merits medical attention and assistance. Over time the Western worldview has become more understanding of the connections between physical and mental health but the socially constructed difference still affects individuals and families. In this chapter, we will talk about both physical and mental health; chapter 6 will focus on mental health.

5.5.1 Models of Care

In the quest for quality health care, one of the issues currently being discussed is that of the focus on treating problems as they appear instead of working to prevent the problems in the first place. This is better known as the medical model versus wellness model of healthcare. In the medical model, providers address the needs of the consumer when problems are presented. This can be equated to fixing a machine when it breaks down. This reactive approach is dedicated to diagnosing and treating illness when a patient presents with a problem. The wellness model, on the other hand, is focused on helping consumers maintain their health, preventing illness, and working with sick patients to make long-term improvements to their health.

In 1978, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed moving away from the medical model, viewing health more as a dynamic way of being instead of a specific goal to achieve (WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the primary health care: Transforming vision to action, 2020). Today, we use the wellness model of healthcare to better understand how daily habits and regular preventative care can add to the positive health of an individual. If you are a human services worker in a medical setting you may be involved with helping to educate individuals, or a community about the benefits of preventative care and to teach them how to get and stay healthy.

5.5.2 Health and Well-Being

Current longevity in the United States has been greatly impacted by advances in medicine. We have come a long way from the medieval practices of blood-letting and using bottled flatulence to ward off the Black Death. It seems that every day there is a new study, revolutionary drug, or innovative procedure that can improve outcomes for people of every age. Health-care services, therefore, can still greatly improve someone’s quality of life, whether they get cured, their illness is managed, or they are made comfortable as they approach the end of their life. However, Americans lag behind their counterparts in other countries around the world when it comes to our health. Compared to our peers in 16 similar high-income nations, such as Japan, China, Britain, and Australia, the United States is worse in several areas, including infant mortality, injuries and homicides, heart disease, and disability (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2013). The same report identified inaccessible and unaffordable health care, poor diet and lifestyle choices, poverty, and convenience as factors in the disparity between the United States and similar countries.

There are inequalities within the United States as well. Family and individual health is affected by the environments in which people live, work, learn, and play. Social determinants of health such as. social engagement, access to resources, safety, and security are all impacted by the settings where families spend their time. Simply put, place matters when it comes to health. To read more about the Social Determinants of Health model, consult https://health.gov/healthypeople.

Health disparities are linked to the social determinants of health. They are preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations (CDC, 2008). Populations can be defined by factors such as race or ethnicity, gender, education or income, disability, geographic location (e.g., rural or urban), or sexual orientation. Health disparities are directly related to the historical and current unequal distribution of social, political, economic, and environmental resources.

Health disparities result from multiple factors, including

- Poverty

- Environmental threats

- Inadequate access to health care

- Individual and behavioral factors

5.5.2.1 Race and Ethnicity

When looking at the social epidemiology of the United States, it is hard to miss the disparities among races. The discrepancy between Black and White Americans shows the gap clearly; in 2008, the average life expectancy for White males was approximately five years longer than for Black males: 75.9 compared to 70.9. An even stronger disparity was found in 2007: the infant mortality, which is the number of deaths in a given time or place, rate for Blacks was nearly twice that of Whites at 13.2 compared to 5.6 per 1,000 live births (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). According to a report from the Henry J. Kaiser Foundation, African Americans also have higher incidence of several other diseases and causes of mortality, from cancer to heart disease to diabetes (James, 2007). In a similar vein, it is important to note that ethnic minorities, including Mexican Americans and Native Americans, also have higher rates of these diseases and causes of mortality than Whites.

5.5.2.2 Socioeconomic Status

Discussions of health by race and ethnicity often overlap with discussions of health by socioeconomic status since the two concepts are intertwined in the United States. A federal report notes, “racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to be poor or near poor,” so many of the data pertaining to subordinate groups is also likely to be pertinent to low socioeconomic groups (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010). Research has consistenly found that “one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of a person’s morbidity and mortality experience is that person’s socioeconomic status” (Winkleby, Jatulis, Frank, & Fortmann, 1992). This finding persists across all diseases with few exceptions, continues throughout the entire lifespan, and extends across numerous risk factors for disease.” Morbidity is the incidence of disease.

It is important to remember that economics are only part of the SES picture; research suggests that education also plays an important role. Many behavior-influenced diseases like lung cancer (from smoking), coronary artery disease (from poor eating and exercise habits), and AIDS initially were widespread across SES groups (Phelan & Link, 2003).

5.5.2.3 Education

Health disparities are also related to inequities in education. Dropping out of school is associated with multiple social and health problems, including substance abuse, and increased depression among girls. ( McCarty et al, 2008; Ellickson, Saner, & McGuigan, 1997). Overall, individuals with less education are more likely to experience a number of health risks, such as obesity, substance abuse, and intentional and unintentional injury, compared with individuals with more education (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Higher levels of education are associated with a longer life and an increased likelihood of obtaining or understanding basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (Jemal et al, 2008; Breese et al, 2007).

5.5.2.4 Gender and Sex

Women are affected adversely both by unequal access to and institutionalized sexism in the health-care industry. According to a recent report from the Kaiser Family Foundation, women experienced a decline in their ability to see needed specialists between 2001 and 2008. In 2008, one quarter of women questioned the quality of her health care (Rangi & Salganico, 2011). In this report, we also see the explanatory value of understanding intersectionality and intersection theory which suggests we cannot separate the effects of race, class, gender, sex, sexual orientation, and other attributes as factors of marginalization. Further examination of the lack of confidence in the health-care system by women, as identified in the Kaiser study, found, for example, women categorized as low income were more likely (32 percent compared to 23 percent) to express concerns about health-care quality, illustrating the multiple layers of disadvantage caused by race, gender, and sex.

We can see an example of institutionalized sexism in the way that women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with certain kinds of mental disorders. Seventy-five percent of all diagnoses of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) are for women, according to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Becker, n.d.). This diagnosis is characterized by instability of identity, of mood, and of behavior, and Becker argues that it has been used as a catch-all diagnosis for too many women. She further decries the pejorative connotation of the diagnosis, saying that it predisposes many people, both within and outside of the profession of psychotherapy, against women who have been so diagnosed.

Many critics also point to the medicalization of women’s issues as an example of institutionalized sexism. Medicalization refers to the process by which previously normal aspects of life are redefined as deviant and needing medical attention to remedy. Historically and contemporaneously, many aspects of women’s lives have been medicalized, including menstruation, premenstrual syndrome, pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause.

Whether it is addressing the problems inherent in our system of health care or we are working with clients to navigate medical services, human services practitioners are an integral part of clients’ overall health. They can help patients to bridge the gap between the expertise of medical professionals and adapting to health changes in their lives. They help resolve gaps in needs and resources., by helping clients and their families connect to the proper medical services, logistically plan for their situation, and deal with any illness, injury, or disability on a biopsychosocial and spiritual level.

5.5.3 Health and Health Insurance

Industrialized nations throughout the world, with the notable exception of the United States, provide their citizens with some form of national health care and national health insurance (Russell, 2018). Although their health-care systems differ in several respects, their governments pay all or most of the costs for health care, drugs, and other health needs. In Denmark, for example, the government provides free medical care and hospitalization for the entire population and pays for some medications and some dental care. In France, the government pays for some of the medical, hospitalization, and medication costs for most people and all these expenses for the poor, unemployed, and children under the age of ten. In Great Britain, the National Health Service pays most medical costs for the population, including medical care, hospitalization, prescriptions, dental care, and eyeglasses. In Canada, the National Health Insurance system also pays for most medical costs. Patients do not even receive bills from their physicians, who instead are paid by the government. Medical debt and bankruptcy due to accident or disease is a uniquely American problem.

These national health insurance programs are commonly credited with reducing infant mortality, extending life expectancy, and, more generally, for enabling their citizens to have relatively good health. Notably, the United States ranks 33 out of 36 countries who belong to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for infant mortality. The infant mortality rate in the United States is 5.9 deaths per 1,000 live infant births, as compared to the average rate of 3.9 deaths per 1000 births. Five countries have death rates lower than 2 per 1,000 births. Their populations are generally healthier than Americans, even though health-care spending is much higher per capita in the United States than in these other nations. In all these respects, these national health insurance systems offer several advantages over the health-care model found in the United States (Reid, 2010).

5.5.3.1 Access to Health-Care Coverage and Insurance

Access to health care is inequitable in the United States, and as human services practitioners it is critical to view this as a social problem and not a personal failing. When people have less access to health care, or have to choose between medical visits, prescriptions, food, and housing, they are less likely to be able to achieve and maintain good health.

There are many insurance options in America, and we will see that they disproportionately benefit some and disadvantage others based on factors like sex, income, geographical location, and ethnicity. In 2017, some of the most common ways people accessed insurance was through private plans; employer-based (56%), direct purchase (16%), or, through government plans; Medicaid (19.3%), Medicare (17.2%), and military health care (4.8%) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). To learn more about how people accessed health insurance coverage, and who remained uncovered, watch this seven-minute video provided by the United States Census Bureau (figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5. Click on the image above or on this link to view the video.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was created to make health care less costly and less discriminatory in 2010. In 2016, section 1557 provided new regulations to the Affordable Care Act, including a way to enforce civil rights protections in health care by making it unlawful for health-care entities to discriminate against protected populations if they receive any type of federal financial assistance. This included health insurance companies participating in the Health Insurance Marketplaces, providers who accept Medicare, Medicaid, and Child Health Insurance Program (CHIP) payments, and any state or local health-care agencies, among others. This marked the first time that discriminatory practices on the basis of race, skin color, national origin, age, sex, disability status–and in some cases, sexuality and gender identity–were broadly prohibited in the arena of public and private health care (Rosenbaum, 2016).

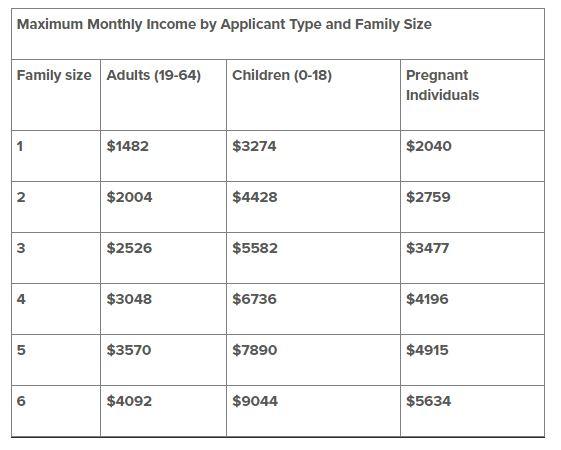

Some of the common ways that lower income families and individuals access insurance in Oregon are through programs like Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Programs (CHIP): which is referred to as Oregon Health plan (OHP) in Oregon. Oregon is one of 39 states that elected to expand Medicaid since 2014 when the ACA made that possible.This has resulted in many more Oregonians having access to health care. Figure 5.6 shows eligibility requirements.

Figure 5.6 Consult the OHP website for more information about what factors other than income relate to eligibility for the Oregon Health Plan in 2022.

The fact that 39 states have expanded eligibility, but 12 have not, points out the inequities people face based on geography. Medicaid is a federal and state funded program that is managed by individual states. It provides government insurance to those who need it. Each state has the power to decide who is eligible for it, and most states focus on low-income individuals, and those with disabilities. For up to date information on each state, consult this Kaiser Family Foundation interactive map and narrative.

The U.S. government’s website about Medicaid (https://www.medicaid.gov) provides state by state report cards on a wide variety of health access and health quality measures. This variance in Medicaid eligibility creates great inequity for low-income families based on location. Those in states that have not expanded Medicaid face a much larger “coverage gap,” meaning that many more families do not have access to health-care insurance.

Those who are age sixty-five or older can access healthcare insurance through Medicare, which is federally funded. Medicare covers about half of health-care expenses for those enrolled, and many retirees who can afford to do so purchase private insurance or purchase additional coverage from Medicare itself to cover the gap (MedPac, 2020).

5.5.3.2 Case Study: Tahir

- What services would help Tahir stabilize his health and work life?

- How would universal health care help Tahir?

- What other problems is Tahir at risk for if he doesn’t have adequate health care?

5.5.4 Working in Health Care

There are many different types of health-care jobs and careers for human services practitioners. Some require specializations with social work or counseling, which require a master’s degree. But opportunities in health care for non-licensed jobs continue to grow. Degrees and licenses will be discussed in Chapter 11. Following is a sample of the jobs and careers for helping professionals work in health care.

5.5.4.1 Medical Social Workers

Medical social work is a specific form of specialized medical and public health care that focuses on the relationship between disease and human maladjustment. Medical social workers practice in a variety of health-care settings such as hospitals, community clinics, preventative public health programs, acute care, hospice, and outpatient medical centers that focus on specialized treatments or populations. These professionals help patients and their families through life changing and sometimes traumatic medical experiences.

All medical social workers must familiarize themselves with cross-cultural knowledge in order to provide effective health care. They do this by familiarizing themselves with an array of different ethnicities, cultural beliefs, practices, and values that shape their family system. In addition, they must practice cultural humility as described in Chapter 1, to learn about each client, their family, and culture. Medical social workers must have the ability to recognize how oppression can affect an individual’s bio-psycho-social-spiritual well-being.

5.5.4.1.1 Emergency Room Social Workers

Within hospitals, there are several specialties where social workers may focus. For example, they may work in an emergency room where they provide services to triage patients. One of their main functions is to diagnose and assess patients who show signs of mental illness. The medical social worker also performs discharge planning as a means of assurance that every patient will have a safety plan when discharged from the hospital (Fusenig, 2012).

The following is a list of tasks that emergency room social workers may perform:

- Stress, mental health, and suicide assessments

- death notifications to family members

- Counseling and other referrals

- child and adult protective service reporting

- domestic violence and sex trafficking screenings

- discharge planning

5.5.4.1.2 Hospice and Palliative Care Social Workers

Palliative care involves a team of professionals who provide comprehensive wellness services, including physical and mental health care, to patients with terminal and chronic illnesses. This is closely related to hospice care, which is specifically for those with a terminal illness. The main idea of this treatment option is to provide respectful and compassionate care for patients in order to have as balanced a perspective as possible on the life they have remaining. Care can take place in a hospital, assisted living center, or a patient’s home.

The following is a list of tasks that hospice and palliative care social workers perform:

- ensuring that patients and family members have access to resources that will provide physical comfort;

- providing emotional and or spiritual support to patients and their family members;

- lead support groups for family members and in-service trainings to nurses, physicians, and other social workers who are involved in the treatment process; and

- ensure proper medical transitions from palliative care to hospice care if needed

- act as care coordinators; providing treatment planning with other members of the patient’s treatment team (socialworklicensure.org, 2017).

5.5.4.1.3 Pediatric Social Workers

Another kind of specialized care involves working with children and their families. Children who are experiencing chronic or terminal illnesses need support related to their mental health. A knowledge of overall child development, as well as family systems is important to be able to perform this job. Pediatric social workers provide emotional and planning support to children and families in hospital, outpatient, and home settings.

5.5.4.2 Public Health Work

Public health work addresses communicable diseases, poverty, sanitation, and hygiene. It is defined as a collection of human service programs that has a common goal: identify, reduce and or eliminate the social stressors among the most vulnerable populations. A public health worker’s main role is to establish preventative measures and to intervene in the health and social problems that affect communities and populations.

Roles that helping professionals play in public health include:

- find people who need help

- assess the needs of your clients, their situations and support networks

- come up with plans to improve their overall well-being

- help clients to make adjustments to life challenges, including divorce, illness and unemployment

- work with communities on public health efforts to prevent public health problems

- assist clients in working with government agencies to receive benefits

- respond to situations of crisis, including child abuse or natural disasters

- follow up with clients to see if their personal situations have improved (allen & spitzer, 2015)

Public health work is also critical at the macro level where prevention, health equity, and building evidence are core principles (CDC, 2014.) At the national or state level this can improve access to quality care for those marginalized in society. Strategies focus on community resources, many of which are nonprofit agencies, addressing behavioral aspects contributing to overall health.

5.5.4.2.1 Community Social Workers

Community social workers are key constituents in implementing these efforts. While programs and strategies might vary, social work practice in community health and prevention can focus on a wide variety of topics, including smoking, family nutrition, teen pregnancy, drunk driving, and sexual health to name a few, that can impact the overall physical and mental health of the community and its members quality of life. Unlike primary care and mental health settings addressing health-care concerns that align more with the medical model, community health and prevention follows the wellness model by working to identify and prevent physical and mental health problems, and does so on a broad scale.

5.5.4.3 Sex and Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is defined as the recruitment, transportation, and or harboring of a person by means of threat, force or another form of coercion, abduction, fraud, and deception. It is through the abuse of power over vulnerable individuals that perpetrators are able to exploit them. It is often combined with extreme violence, torture and degrading treatment that leave psychological wounds for the rest of their lives. Human and sex trafficking is a violation of human rights. It is estimated to affect more than two million victims worldwide (Ahn, Albert & et.al, 2013; Gajic-Veljanoski & Stewart, 2007).

There are two primary forms of human tracking: forced labor and sex trafficking. This section focuses on sex trafficking due to the increased prevalence and on the roles that human services and social workers take to identify victims and to provide proper medical care (Gajic-Veljanoski & Stewart, 2007).

Professionals play a vital role in the identification of victims. Victims may be reluctant to disclose their experiences due to the fear of law enforcement, repercussions to family members and the lack of awareness of agencies that offer services specific to the population.

Medical social workers can help eliminate the potential of sex trafficking by:

- Identifying victims and assist them with the proper resources for medical, psychological and shelter;

- Serving on organizational committees or as board members who specifically focus on assisting sex trafficking victims and help to improve rehabilitation and reintegration into society and;

- Educating vulnerable populations such as children in schools or sex-workers that come through the emergency room on possible preventative measures and signs of trouble. (Salett, 2006; Ahn, Albert & et.al, 2013)

There are other specializations in human services and social work as related to medical care. These specialties shift and change over time. If you are interested in the overlap between medical care and being a helping professional, it is recommended to perform exploration activities such as informational interviews, job shadowing, and internships to learn about the roles and structures in these environments.

In this chapter we examined the many ways that human services can be organized and focused especially on health care settings. Mental health is a very important part of overall health and because it is such a large focus for human services, Chapter 6 is fully devoted to mental health.

5.5.5 References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2010). The 2010 National Healthcare Disparities Report. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr10/index.html

Ahn, R., Alpert, E. J., Purcell, G., Konstantopoulos, W. M., McGahan, A., Eckardt, M. . . . Burke, T. F. (2013). Human trafficking: Review of educational resources for health professionals. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(3), 283-289. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.025.

Allen, K. M., & Spitzer, W. J. (2016). Social work practice in healthcare: Advanced approaches and emerging trends. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Becker, Dana. n.d. Borderline Personality Disorder: The disparagement of women through diagnosis.” Retrieved December 13, 2011 from http://www.awpsych.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=109&catid=74&Itemid=126

Breese, P. E., Burman, W. J., Goldberg, S., & Weis, S. E. (2007). Education level, primary language, and comprehension of the informed consent process. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 2(4), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2007.2.4.69

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Community Health and Program Services (CHAPS): Health disparities among racial/ethnic populations. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). About DCH. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/about/index.htm.

Ellickson, P., Saner, H., & McGuigan, K. A. (1997). Profiles of violent youth: Substance use and other concurrent problems. American Journal of Public Health, 87(6), 985–991. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.87.6.985

Fusenig, E. (2012, May). The role of emergency room social worker: An exploratory study. Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers. Paper 26

Gajic-Veljanoski, O., & Stewart, D. E. (2007). Women trafficked into prostitution:Determinants, human rights and health needs. Transcultural Psychiatry, 44(3), 338-358.

Gehlert, S., & Browne, T. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of health social work (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. (2013). U.S. health in international perspective: Shorter lives, poorer health. National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/US-Health-International-Perspective/USHealth_Intl_PerspectiveRB.pdf.

James, C. et al. (2007). Key facts: Race, ethnicity & medical care. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://www.kff.org/minorityhealth/upload/6069-02.pdf.

Jemal, A., Thun, M. J., Ward, E. E., Henley, S. J., Cokkinides, V. E., & Murray, T. E. (2008). Mortality from leading causes by education and race in the united states, 2001. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34(1), 1-8.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.017

McCarty, C. A., Mason, W. A., Kosterman, R., Hawkins, J. D., Lengua, L. J., & McCauley, E. (2008). Adolescent school failure predicts later depression among girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.023

MedPac. (2020, March). Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_entirereport_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

Mizrahi, T., & Davis, L. E. (2008). The encyclopedia of social work (20th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2012). Social workers in hospital and medical center: Occupational profile. Washington, DC: NASW. Retrieved from http://workforce.socialworkers.org/studies/profiles/Hospitals.pdf (this link needs to be updated)

National Association of Social Workers. (NASW). (2016). NASW standards for social work practice in health care settings. Washington, DC: NASW. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=fFnsRHX-4HE%3D&portalid=0

Phelan, Jo C., & Link, B. G. (2003). When income affects outcome: Socioeconomic status and health. Research in Profile, 6.

Ranji, U., & Salganico, A. (2011). “Women’s health care chartbook: Key findings from the Kaiser Women’s Health Survey.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/report/womens-health-care-chartbook-key-findings-from/

Reid, T. R. (2010). The healing of America: A global quest for better, cheaper, and fairer health care. Penguin Books

Rosenbaum, S. (2016, September). The Affordable care act and civil rights: The challenge of Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act. Milbank Quarterly, 94. https://www.milbank.org/quarterly/articles/affordable-care-act-civil-rights-challenge-section-1557-affordable-care-act

Russell, J. W. (2018). Double standard: Social policy in Europe and the United States (Fourth edition). Rowman & Littlefield

Salett, E. P. (2006, November). Human trafficking and modern day slavery. Human Rights and International Affairs Practice Update

Social Work Licensure.org. (2017). Palliative and hospice social workers and how to become one. Retrieved from http://www.socialworklicensure.org/types-of-social-workers/palliative-hospice-social-workers.html

U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012. 131st ed. Washington, DC. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab

U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). Coverage numbers and rates by type of health insurance: 2013, 2016, and 2017 [table]. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/tables/p60/264/table1.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). Healthy People 2010 objectives: Educational and community based programs.

WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the primary health care: Transforming vision to action. (2020, December) from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-primary-health-care-transforming-vision-to-action

Winkleby, M. A., Jatulis, D. E., Frank, E., & Fortmann, S. P. (1992). Socioeconomic status and health: How education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Public Health, 82(6), 816–820. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.82.6.816

5.5.6 Licenses and Attributions for Understanding and Working in Health-Care Settings

5.5.6.1 Open Content, Original

“Understanding and Working in Health Care Settings” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

5.5.6.2 Open Content, Shared Previously

“Health and Well-being” adapted from Physical Health and Well-Being in Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, is licensed under CC BY 4.0 and Health Equity by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Amy Huskey, Jessica N. Hampton, and Hannah Morelos in Contemporary Families 2e and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: Minor editing for clarity; shortened; refocus of content on to human services.

“Health and Health Insurance ‘ is adapted from Health and Health Insurance by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Jessica N. Hampton, and Christopher Byers in Contemporary Families 2e and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: Updated; minor editing for clarity; shortened; refocus of content on to human services.

Figure 5.5 “Income, Poverty and Health Insurance – Health Insurance Presentation” by The Census Bureau is in the public domain.

Figure 5.6 “Do You Qualify” by CareOregon is in the Public Domain

“Case Study: Tahir” is adapted from Financing Quality Healthcare in Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, is licensed underCC BY 4.0 . Adaptation: minor editing for clarity.

“Working in Health Care” is adapted from “Social Work and the Health Care System “ by Katlin Ann Hetzel and Department of Social Work in Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: updated; edited for clarity, accuracy, and brevity; refocus of content within context of human services.

“Models of Care” is adapted from “Treatment vs. Preventive Care” in Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, is licensed underCC BY 4.0 . Adaptation: minor editing for brevity and clarity; updated references.