7.4 Child Welfare

7.4.1 Indian Child Welfare Act

In November of 2022, the U.S. Supreme Courts heard arguments in Haaland v. Brackeen, which challenges the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA). Watch the video in fig. 7.5 in for a quick overview of the main arguments of the case. As of this writing, the court has not issued a ruling in the case, but many expect that if the court strikes down portions of the law. This could have serious ramifications, not only in terms of the well being of Native American/Native Alaskan (NA/AN) children and families, but for a broad slate of issues related to tribal sovereignty.

Figure 7.5 This 3.56 minute video from University of Washington School of Law explains the history and main arguments of Holland v. Brakeen.Three-Minute Legal Talks: United States Supreme Court case Brackeen v. Haaland

The practice of removing NA/AN children from their families and placing them in boarding schools and in non-indian families, had its roots in the assimilationist policies of the U.S. Government, which sought to “Americanize” NA/AN children, who were considered by White Americans to be “uncivilized”. After more than a century of indian removal policies, which reduced the territory held by sovereign NA/NA people, leaving many impoverished and vulnerable to illness and exploitation. Between 1819 and 1969, the United States operated or supported 408 boarding schools in 37 states or territories (Newland, 2022). Researchers are still trying to determine exactly how many children were removed from their families during this period.

We do know that by the time ICWA was enacted in 1978, 25%–35% of all NA/AN children had been removed from their homes by state child welfare agencies, and of these, 85% were placed in homes outside of their communities. During the 50’s, 60’s and early 70’s. more than 80% of NA/AN families had children removed from their homes by the government (NARF, 2007). By contrast, in 2020, the total number of removals for all children in the U.S was .03% (ACEF. 2022).

ICWA was considered to be a major advancement for tribal sovereignty and self-determination. The Casey Family Foundation, one of 26 child welfare and adoption agencies who filed a brief in support of ICWA, asserts that the principles of family preservation that ICWA advances represent are a “gold standard” in child welfare for all children and families (CFP, 2022). In their strategy brief, Strong Families , these principles include, acknowledging and protecting children’s rights to be connected to their family; supporting efforts to preserve and reunify families; valuing inclusive and diverse cultural practices; and prioritizing authentic tribal engagement.

CFP’s strategy brief reflects a significant trend in the child welfare field towards family preservation and reunification. In 2018, The Family First Prevention Services Act codified this shift by providing prevention funds for mental health services, substance use treatment, and skills training for parents. According to the Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, “This law significantly shifts how the country provides services for families and youth. In particular, it changed the role of community service providers, how courts advocate and make decisions for families, and the types of placements that youth placed in out-of-home care experience.”(Child Welfare Information Gateway 2023) This shifting posture is based on overwhelming data that demonstrates the profound long-term harms of out-of-home placement, which we will discuss in the next section.

7.4.2 Child and Family Services

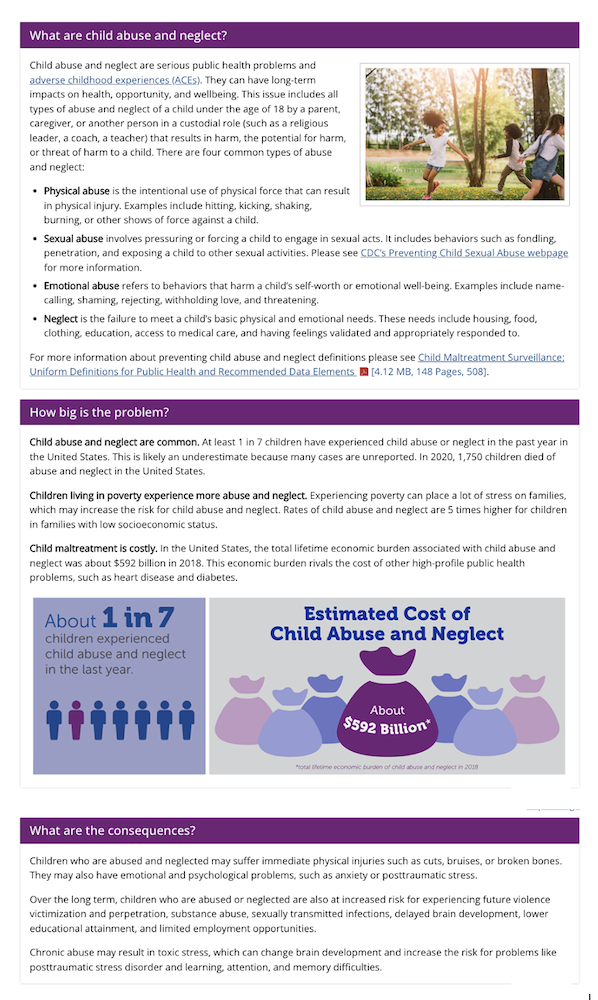

Figure 7.6 “Facts about Child Abuse” from the CDC demonstrate that child abuse and neglect are a significant social problem.

As figure 7.6 illustrates, child abuse, neglect and exploitation are a significant social problem. The U.S. child welfare system is a public response to the social problem of child abuse which is more formally known as child maltreatment. The three goals of child welfare are safety, permanency, and well-being. A network of federally funded State and Tribal child welfare agencies provide a variety of county-level services to insure the safety, permanency and well-being of children, youth, and their families.

Federal funding is allocated by Congress. Most child welfare funding comes from the Social Security Act, including Title IV-E, and provides funding for foster care, adoption assistance, guardianship, and programs to help stabilize youth and young people who transition out of foster care. In 2019, congress expanded Title IV-E funds to include evidence-based programing to reduce removals by supporting at-risk families.

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), originally enacted in 1974, provides federal funding and guidance to States and Tribes to support of prevention, assessment, investigation, prosecution, and treatment activities and also provides grants to public agencies and nonprofit organizations, for demonstration programs and projects. Additionally, CAPTA identifies the federal role in supporting research, evaluation, technical assistance, and data collection activities; establishes the Office on Child Abuse and Neglect; and establishes a national clearinghouse of information relating to child abuse and neglect. CAPTA also sets forth a Federal definition of child abuse and neglect.

State-level funding can also include Medicaid and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) programs, and the Social Services Block Grant, as well as the Supplemental Security Income program (SSI).

Child Welfare services in Oregon are administered by the Oregon Department of human services (ODHS), which operates 45 Child Welfare sites throughout the state. State Child Welfare services include Child Protective Services (CPS), foster and kinship care, adoption support, and the Independent Living Program (ILP) for transition-age youth and young people. The ODHS in Salem also houses the ODHS Indian Child Welfare Manager. Six Tribal child Welfare Programs in Oregon are regulated by the Oregon Indian Child Welfare Act (ORICWA).

People who witness child abuse or think a child is being hurt, can call 911 or the Oregon Child Abuse Holtine (ORCAH), at 1-855-503-SFAE (7233). Medical providers, school employees, clergy, and other people who work with children, are mandated reporters, who can face legal consequences for failing to report child maltreatment. In 2021, ORCAH recorded 162,184 “contacts” (calls to the hotline or police reports). Of those 78,775 “screened” as reports of suspected child maltreatment. Screened-in reports can be information only, referral to other services, not a situation that is child abuse or neglect, or possible child abuse and neglect.

Child Protective Services (CPS) and law enforcement agencies share responsibility for investigating child maltreatment. In 2021, 34,407 assessments were completed. CPS workers assess reports by interviewing children, families and others who may be familiar with the child’s situation, like neighbors and educators. The purpose of the investigation is to determine if the child has been abused, and if they are safe in their present situation. In 2021, 7,352 of the assessed reports found abuse, affecting 10,766 children. Threat of violence (46.8%) and neglect (32.5%) constituted most abuse findings in these cases.

In cases where there is a finding of abuse or neglect, CPS workers and law enforcement will assess further to determine if the child can safely remain at home. Safety planning may include requiring the offending parent to move out of the home and specific in-home services. There are two categories of in-home safety plans. In-Home Safety and Reunification Services (ISRS) and the Strengthening, Preserving and Reunifying Families Program (SPRF) may include culturally appropriate in-home case management or supervision, assistance accessing stable housing, health care services, and other basic needs, parenting classes, peer-based parenting supports, and respite care. The goals of in-home services are to stabilize families, keep children safe, and reduce removals. SPRF services also aim to support family reunification, reduce the length of time children spend in out-of-home care, and reduce the rates of reentry into the child welfare system.

In 2021, 18.4% of cases where abuse was found resulted in the removal of 1,983 Oregon children from their homes. When it is determined that a child cannot safely remain at home they are placed with a relative or in“substitute care”, an out-of-home placement. Out of home placements are reviewed within 24 “judicial hours”, the hours that court is open for business. It is ultimately up to the court whether a child remains in care or returns home. When children are placed in care, in-home services are usually provided to support for families in the reunification process. In 2021, 54% of children exiting care were reunited with their families.

If a child has been abused, law enforcement takes responsibility for any necessary criminal procedures, including filing reports of criminal behavior. When criminal charges are warranted, a district attorney is responsible for filing charges and prosecuting a case. In these cases, district attorneys coordinate services with multidisciplinary teams that may include ODHS personnel, school officials, medical providers and law enforcement.

Black children, children who identify as LGBTQ+, and children in poverty are significantly overrepresented in child removal statistics. For example, about 14% of the children in the U.S. are Black, yet black children accounted for 23% of children in foster care in 2021(AECF 2022). That number is down from 29% a decade ago, which does indicate that the system as a whole, from the Childrens’ Bureau to state agencies, along with nonprofits that work with youth in care are taking racial inequity, gender and class-based inequities seriously. Yet the disparities remain stubbornly high.

Many low income families who interact with child and family services report feeling like they are being punished for being poor (HRW, 2022). 16% of children in the U.S. were living in poverty in 2020 (AECF 2022), yet the majority of children who are identified as victims of child maltreatment live in poverty. It is true that CDC cites poverty as a risk factor for child abuse and neglect (fig. 7.6), however children who are low income are also more likely to be subject to mandated reporting because of their increased involvement with social services. In other words, families who are seeking help to meet their childrens’ basic needs are more likely to be reported than families who are well-resourced.

LGBTQ+ youth are twice as likely to experience foster care than children who do not identify as LGBTQ+. They experience higher rates of physical and psychological abuse in their homes, and they are more likely to run away or be rejected from their homes. Once in care, LGBTQ+ youth are not always well served by the child welfare system. They are more likely to experience discrimination and rejection from foster families, experience bias from case managers, and to experience multiple placements (Fish et al., 2019).

Unconscious bias among child welfare workers and foster families has been identified as a major cause of these disparities. Many who work in the field can easily remember having been taught to treat people fairly and avoid discriminating against people. However, in a society that is stratified by race, gender, and class, those are not the only lessons we learn about difference. It can sometimes be harder to recognize the socially constructed biased ideas we internalize. To reduce harm, it is critical that child welfare workers be proactive about recognizing and questioning our biases. Out of Home Placements

Figure 7.7 Types of foster placements include at-home family placement, kinship placement, resource placements, therapeutic placements, and residential treatment.

The foster care system supports safety, well-being and permanence for children who experience maltreatment, including abuse, neglect and sexual exploitation. Fig. 7.6 describes the range of placements available to youth. These include at-home family placement, kinship placement, resource placements, therapeutic placements, and residential treatment.

Resource parents, also known as foster parents open their homes to children and youth not safe with their parents or caregivers. When children are not safe in their homes the support of caring child welfare professionals and loving resource families can provide safety and may provide meaningful relationships that can serve as protective factors to mitigate against some long-term effects of abuse. However, the research is clear that removing children from their families is harmful. Harms can be measured in both long-term and short-term impact including, disruption to school, loss of peer support, higher rates of depression and anxiety, substance use disorder, criminal justice involvement, and a higher risk of housing insecurity later in adulthood.

These harms increase significantly with multiple placements. Placement instability occurs when children experience two or more placements during care. While most children who are in care for less than a year experience two or fewer placements, placement insecurity increases the longer a child is in care. One-third of children in care for two years experience two or more placements, and that number doubles for children who are in care longer than two years. Youth who experience multiple placements are less likely to achieve permanency, have a harder time in school, and struggle to form meaningful peer connections.

In Oregon, every effort is made to find permanent placement, where a child can stay until they are reunified with their family or adopted by a new forever family. In cases where permanent placements are not available, a child may be placed in shelter care for up to 20 days, until a permanent placement is available. In order to reduce the harms of family separation, advocates for youth in care call for child welfare systems to strive for “first placement, best placement, family placement, only placement”(CFP 2022).

Family-based kinship placements, in which children are placed with relatives, are given preference in Oregon. In the event that removal becomes necessary, every effort should be made to identify family (kin) or chosen supportive adults (fictive kin). Kinship providers are required to go though the same training and certification as other resource parents, and receive the same financial and material support. Supportive adults unrelated to a child can also become certified as child-specific resource parents. In 2021 46.2% of youth in care were placed with their own family members.

All resource parents are required to attend an orientation and undergo a SAFE (Structured Analysis Family Evaluation) home study, as well as complete a 27-hour Resource and Adoptive Family Training (RAFT). Recertification requires 30 hours of ongoing training each year.

Therapeutic foster parents offer a safe home-based intervention for children with severe emotional and behavioral disorders. In Oregon, Treatment Foster Care Oregon (TFCO) offers evidence-based support in a 9-month program for at-risk youth that help “youth to successfully live in a family setting” and “to simultaneously help parents (or other long-term family resource) provide effective parenting” (TFSC, 2023) Therapeutic foster parents receive specialized training and are supported with on-call clinical support.

For children with complex behavioral or physical needs who cannot be placed in with a suitable resource family, residential treatment in a congregate setting is an option, however the unnecessary placement of children in institutional settings can exacerbate harm and should be a last resort. In order to reduce the overuse of reliance on congregant placements, the 2019 Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) redirected funding away from residential treatment centers towards prevention and family-based placements.

Special attention is also given to maintaining connections between siblings in care. Whenever possible, siblings are placed together. When this is not possible, resource families and CPS work together to help siblings keep in contact with each other and have regular visits. In 2021, 83.6% of sibling groups were placed together.

7.4.3 Exiting Care

In spite of the term, permanent placement, which specifically refers to the time a child is in care, foster care is not intended to be permanent. Every child in care has a case plan that outlines the necessary steps to bring children home. During reunification, families, CPS, courts and other community service providers work together to remove barriers to reunification. If it is safe to do so parents are encouraged to maintain contact with their children and visit regularly. Steps to reunification can include substance use treatment, anger management counseling, parenting and peer support classes, and securing stable employment and housing. In 2021, 54.3 % of the 8, 620 children who were placed in substitute care were reunified with their families.

In Oregon, ODHS is legally authorized to assume permanent custody of a child when a parent’s rights are terminated by the court, when parents relinquish their rights, or when both parents are deceased. In the event that parents are unable to successfully reunify within six months of removal, a case will be amended to include concurrent plans for permanency. Permanency plans can include placement with family, or adoption by another family.

Guardianship is a legal arrangement that does not require parents to relinquish parental rights and allows non-parental caregivers to exercise parental duties on behalf of a child. In some cases guardianship can also be an option if the child is already a ward of the state. Resource parents can become guardians, but it is more commonly used to make kinship placements more permanent. In Oregon guardianship for youth exiting care must be approved by a permanency committee who verify that the child cannot be safely returned home, that the guardianship will meet the child’s needs for safety, well-being and permanence, and that the parent accepts the guardianship plan. In 2021, 351 Oregon children exited care via guardianships.

Adoptive parents make a life-long commitment to welcome a child into their family. Adoption requires birth parents to relinquish parental rights. Many children adopted out of care choose to maintain relationships with the birth parents and families. As with guardianships, adoptions require approval by way of a home study and a period of supervision. In 2021, 683 Oregon children were adopted out of foster care. As of this writing there are approximately 200 children waiting to be adopted in Oregon. Most of them are older, part of a sibling group, are BIPOC, or have disabilities (ODHS 2023). Nationwide, 32% of youth eligible for adoption wait more than 3 years (NACAC 2023).

While most adoptions are successful, as many as 5% of them are either disrupted before finalization or dissolved after they become final. In this case children return to foster care and a new permanency plan is developed. Many failed adoptions are the result of families being surprised by unexpected stress and expensed from previously undisclosed or minimized needs that families were unprepared for. The North American Council on Adoptable Children (NACAC) asserts that disruptions and dissolutions can prevent improved preparation, family selection, and support. They also recommend that States and other placement entities fully disclose a child’s background early in the selection process (NACAC 2023).

Each year more than 23,000 young people in the U.S. age out of care without finding permanence. Of these, about 20% become instantly homeless, when they are discharged congregate facilities or can no longer stay with resource families (NFYI 2023). Even when circumstances are not quite so dire, young people aging out of care face unique challenges. Independent Living Programs (ILPs) connect young people with the resources they need to make a successful transition out of care.

Think about all the things young people rely on their families for as they are moving into adulthood. Not only the nuts and bolts of deciding on college, finding a job, learning how to live on one’s own, but things we may take for granted like, filling out the parents portion of a federal student aid application or signing for a driver’s license, neither of which a resource parent can do. In these cases, the state assumes the responsibility of parents, and an ILP case worker becomes a critical resource. ILP case workers and youth collaborate to create a transition plan, which becomes an individualized roadmap to successful independence for young people exiting care. Youth can enroll in ILP programs as early as age fourteen, and remain eligible for aftercare services, including subsidized housing and educational support, until they turn 24.

Youth and young people are placed in care through no fault of their own. The experience of disruption and relationship loss sets them on a path with unique barriers and obstacles. Research is clear that helping young people build robust networks of lasting meaningful connection, with family of origin where possible, resource families, peers, and caring professionals, help young people build the resilience they need for success. A human services worker is no substitute for a family, but equipped with trauma-informed skills, unconditional positive regard and access to necessary resources, they can help young people thrive in and out of care.

One more thing you should know about youth and young people who experience care. They are awesome! Around the country, networks for former foster youth, known as alumni of care, are working to improve the child welfare system for children who are coming up behind them. Some alumni even choose careers in child welfare. All of the recent reforms in child welfare, including the FFPSA have been inspired, informed, and championed by alumni. State welfare agencies are required to have youth advisory boards, and at the national level, former foster youth and alumni-led organizations regularly lobby lawmakers, sign on to amicus briefs to the courts, and advise the Children’s Bureau and other federal agencies on child welfare policy. They have also created robust peer networks of meaningful connection, helping each other find permanence as they work together to make life better for young people impacted by child abuse, neglect and expoliation (figure 7.8).

Figure 7.8 Robust social networks of lasting meaningful connection can help young people build the resilience they need for success.

7.4.4 Want to Know More?

- For more on how racial bias specifically shows up in child welfare you can check out the resource from Kirwan Institute: Exploring Implicit Bias in Child Welfare .

- To learn more about the Oregon Department of Human Services Child Welfare Programs, click here.

7.4.5 References

Jones, A. S., Rittner, B., & Affronti, M. (2016). Foster parent strategies to support the functional adaptation of foster youth. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10:3, 255-273, p. 255, Quoted in https://www.casey.org/placement-stability-impacts/#:~:text=Safety%20is%20impacted%20when%20a,behavioral%20and%20mental%20health%20issues.\

The Annie E. Casey Foundation. “2022 KIDS COUNT Data Book.” Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.aecf.org/resources/2022-kids-count-data-book.

Casey Family Foundation. Strategy brief: Strong families (2022) Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.casey.org/media/22.07-QFF-SF-ICWA-Gold-Standard.pdf

Cyndi. “51 Useful Aging Out of Foster Care Statistics | Social Race Media | NFYI,” May 26, 2017. https://nfyi.org/51-useful-aging-out-of-foster-care-statistics-social-race-media/.

Guggenheim, Martin, and Hyland Hunt. “BRIEF OF CASEY FAMILY PROGRAMS AND TWENTY-SIX OTHER CHILD WELFARE AND ADOPTION ORGANIZATIONS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF FEDERAL AND TRIBAL DEFENDANTS,” 2022 https://sct.narf.org/documents/haaland_v_brackeen/amicus_casey.pdf

“A Practical Guide to the Indian Child Welfare Act; Native American Rights Fund.” Accessed February 7, 2023. https://narf.org/nill/documents/icwa/index.html.

Fish, Jessica N., Laura Baams, Armeda Stevenson Wojciak, and Stephen T. Russell. “Are Sexual Minority Youth Overrepresented in Foster Care, Child Welfare, and Out-of-Home Placement? Findings from Nationally Representative Data.” Child Abuse & Neglect 89 (March 2019): 203–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.005.

“Implicit Racial Bias 101: Exploring Implicit Bias in Child Protection.” Accessed February 17, 2023. https://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/implicit-bias-101.

Treatment Foster Care Oregon. “Foster Parents.” Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.tfcoregon.com/foster-parents/.

“State of Oregon: Adoption – Adopt a Child.” Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.oregon.gov/DHS/CHILDREN/ADOPTION/Pages/adopt-child.aspx.

The North American Council on Adoptable Children. “Adoption Disruption and Dissolution.” Accessed February 17, 2023. https://nacac.org/advocate/nacacs-positions/adoption-disruption-and-dissolution/.

7.4.6 Licenses and Attributions for Child Welfare

“Child Welfare” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Fig 7.5 “Three-Minute Legal Talks: United States Supreme Court case Brackeen v. Haaland” @University of Washington 2023 Standard YouTube License

Figure 7.6 “Fast Facts about Child Abuse” by Nora Karena, adapted from Centers for Disease Control CAN, Factsheet, 2022 https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/can/CAN-factsheet_2022.pdf

Figure 7.7 “Types of Foster Placement” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 7.8 Photo by Helena Lopes on Unsplash

2021 Oregon Child welfare statistics were adapted from the 2021 Child Welfare Data Book @ 2022 Oregon Department of human services, Office of Reporting, Research, Analytics, and Implementation

Description of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment act from Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2019). About CAPTA: A legislative history. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and human services, Children’s Bureau. – Adapted for length and context.