8.5 Challenges Facing Older Adults and Their Families

As an individual, take a moment to think about what you do to keep yourself as youthful as possible. While not everyone will come up with an answer, a good majority of people will come up with at least one thing they do to combat aging, both physically and mentally. Whether it is working out to stay fit and strong, doing mental aerobics with puzzles to get your wits sharp, or using facial creams and/or plastic surgery to prevent or get rid of wrinkles and other visible signs of aging, many people are trying to stay young for as long as they can. While the impetus for these measures might be to prolong life as long as possible, some strategies Americans use are really more to prolong youth.

As a society, we put so much emphasis on staying young, especially physically. One article reported a study presented at the annual conference for the American Public Health Association that indicated we spent more money on medication targeting what used to be thought of as natural effects of aging, such as “mental alertness, sexual dysfunction, menopause, aging skin and hair loss,” (para. 2) than we do on prescriptions designed to counteract chronic illnesses (Drevitch, 2012). Add this to the amount of money spent on over-the-counter anti-aging creams, makeup designed to cover wrinkles, and hair dye for women and men, and we have a better understanding of how society tries to prevent or avoid the aging process.

Baby boomers are redefining how we look at age. Old age is no longer seen as a time of fragility and senility, but rather a time of wisdom, being active, and purposeful living (Wilson, 2014). In fact, a study conducted by Pew Research found that a majority of American adults feel their life will be as satisfying or better ten years from now, including a two-thirds majority of those who are considered old-aged (Pew Research, 2013).

8.5.1 Ageism

Yet, ageism, or discriminating against older Americans because of their age, is still very prevalent in the U.S. We may be comfortable with our own aging, but we generally do not want to acknowledge it unless we must. Then when we do acknowledge it, it is always with the belief that we will be different—that when we grow old, we will not end up or behave like those who came before us. We will make sure we take care of ourselves, unlike those who we see as the “elderly” now. We may not be internalizing the negative beliefs about getting older as much as we used to, but that does not mean as a group we are completely sold on the usefulness of the aging population.

Ageism can be easily seen in hiring practices, as Americans closer to retiring were displaced from their jobs due to The Great Recession (December 2007-June 2009) and, as a result, try to find new employment. Stereotypes that we have about the elderly are translated into the workplace: older workers are considered less flexible in mindset, work style, and techniques, as well as being less efficient and reliable workers due to physical ability and health (Chou, 2012). These beliefs by employers can result in unfair hiring and firing practices, extended periods of unemployment, and forced retirement (both by the company and by an inability to secure a new job).

Although stereotypes about aging might be based on a safety concern, generalizing behaviors and abilities of a minority percentage of the older population to everyone in this group can cause us to view the older generation as a liability. Take driver’s license requirements for instance. Despite the lower number of crashes and car insurance claims for those 65 years old and over as compared to those under 65—especially the youngest drivers—more than half of all states have specific license renewal requirements for older drivers that may include shorter renewal periods, vision tests, and road exams (IIHS & HLDI, 2015). Essentially, these regulations create an environment in which the aging population is seen as dangerous behind the wheel, when the facts tell a much different story.

Policies and practice are just some ways we write off the older population and how American society demonstrates its bias toward youth. However, it is not always in overt ways that we treat the aging group differently. Another way in which we perpetuate stereotypes can be seen in consumerism and advertising. Products and services related to enjoying life, being active, and any kind of technology are typically marketed to the younger audiences, while the products and services that are about taking care of one’s health, dealing with chronic illnesses, and preparing to live out one’s final years are usually targeting older adults. The fun, the liveliness, and the energy of youth are set aside for quiet, calming, and peaceful tones in commercials for the aging.

These practices perpetuate stereotypes and are based on atypical experiences and an outdated understanding of old age. Defining older adults as physically weak and cognitively inept is incorrect. While some of the aging population may present this way, it is more the exception than it is the rule. Still, we are a long way from eliminating prejudice and discrimination of the aging. Older adults are not universally valued. One study found that while college students did not blatantly discriminate against older people, they did not place importance on spending time with or learning from this group (Yilmaz et al., 2012) . It is not only college students that feel this way. Many people in society behave as if aging adults are outlasting their usefulness to society.

It may seem easy to brush off societal messages (“I don’t pay any attention to ads”; “I laugh at the cards but don’t believe them”), there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that these messages are much more insidious than previously thought. Stereotype Embodiment Theory (SET) posits that the more a person is exposed to ageist messages, the more likely they are to believe–and demonstrate-them themselves (Bengtson and Settersten, 2016). Exposure to negative aging stereotypes is associated with a variety of negative outcomes, including physical, cognitive, and emotional outcomes. Numerous studies (Sargent-Cox, et al., 2015; van Wijndgaarten, et a.l, 2019; Choi, et a.l, 2019) have supported the theory that the more a person is exposed to negative aging messages, the more likely they are to believe these messages. The more they believe these messages, the more likely it is that they suffer from numerous issues, such as the following:

- impaired balance

- cardiovascular disease

- memory problems

- loneliness

Combating negative stereotypes then, is not just a matter of policy, it is a matter of public health.

8.5.2 Ageism in Greeting Cards

Figure 8.7. Here are some examples of negative messages on birthday cards

It is easy to see with just a walk down the greeting card aisle how ingrained ageism is in U.S. culture (figures 8.7). (This phenomenon has also been noted in Canada). Birthdays are seen as a day to celebrate until about the age of 30, which is when the “Over the Hill” messages begin. Most of the cards aimed at adults have a theme of either cognitive or physical impairment, or a sense of impending death. These images and jokes are so prevalent that we almost automatically laugh without considering the underlying message. Several organizations have begun campaigns to fight these ageist messages. (See https://changingthenarrativeco.org/anti-ageist-birthday-cards/ for some examples)

8.5.3 Mental Health Issues in Later Life

There are two distinct areas of mental health concerns in later life. One has to do with improved treatment for serious and persistent mental illness, while the other is related to the management of mental health along with other chronic diseases.

With improved medications and management of diseases like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, people with these issues are able to live longer than previous generations. However, this also means that there is not a lot of research on managing these diseases in older adults. Questions such as appropriate dosage and interactions with other common medications taken by older adults are still being figured out. Another issue is how to manage chronic mental illness along with other chronic diseases. For example, someone may have lived in a group home for their adult life, but now also needs to use a wheelchair. Are the facilities that focus on mental health prepared to care for an aging population, or will they need to move as their care needs increase? Do our current long term care facilities have the ability to handle mental health issues along with physical challenges? These are questions that are being posed right now.

The other focus of mental health in later life is people who develop mental illnesses later in life. This, of course, includes dementia, but depression and substance use are also major issues for older adults. Older adults are often facing multiple losses–due to death, retirement, or changes in physical ability–that can be difficult to accommodate. Some adults struggle after retirement to find purpose and meaning–their 5 o’clock “happy hour” gets earlier and earlier.

Unfortunately, many medical professionals still have difficulty recognizing mental health issues in older patients. I have heard medical professionals say, “If I was in their shoes I’d be depressed, too,” and “They don’t have to work–why worry about how much they drink?” It is important for family members and professionals to understand that depression and substance use are not a normal part of the aging process and can be successfully treated if recognized.

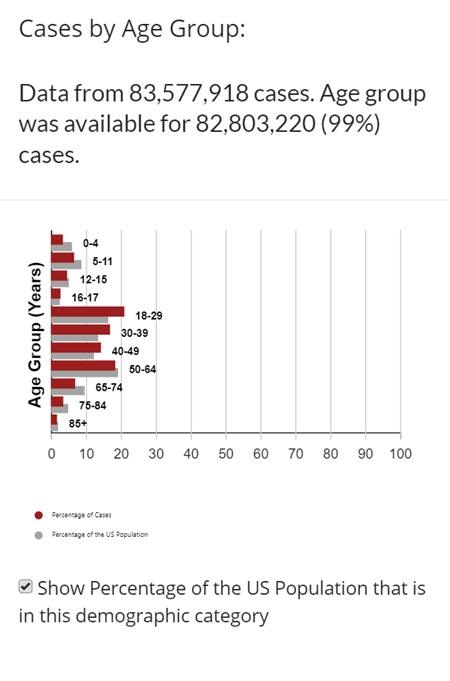

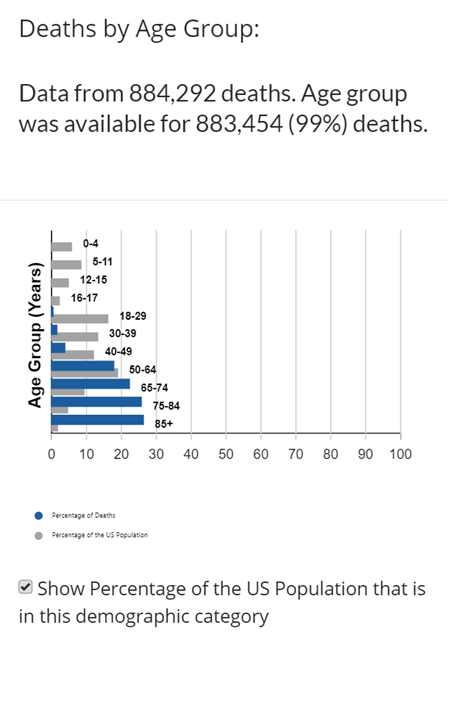

Another more recent crisis was (and continues to be) the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults. One look at the statistics in Figure 8.7 shows us that while older adults were not more vulnerable to getting COVID-19, they were much more vulnerable to having serious complications, including death.

Figure 8.8 CDC Statistics on COVID cases as well as COVID deaths by age.

Figure 8.9 CDC Statistics on COVID cases as well as COVID deaths by age.

Many congregate living facilities (such as nursing homes and retirement communities) had outbreaks that devastated their community. Almost all of the congregate living facilities in the United States closed their doors to visitors for a year or more (figure 8.9). Older adults were isolated from friends and family members, only staying in contact by phone, email, or video chat. This includes multiple instances of family members having to say goodbye to dying loved ones over Zoom or FaceTime.

The Kaiser Family Foundation (2020) reported that anxiety and depression increased in older adults during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression was worse when older adults had other complicating factors, such as other chronic illness or lack of resources. Depression and anxiety were lower when older adults had a feeling that they mattered rather than feeling “expendable”.

However, other studies that compared results between older and younger adults showed that while rates did increase in older adults, anxiety and depression was actually higher in younger adults (Varma et al, 2021). Some speculate that older adults who had lived through other major events displayed more resiliency to the pandemic than younger adults with less experience{(Pearman et. al. 2021; Waugh et. al 2022). It is important we recognize and support these strengths, especially in times of crisis such as a pandemic. And again–we must recognize the diversity or experiences and reactions to the pandemic among older adults.

One research study looked at the prevalence of “compassionate ageism” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Compassionate ageism involves regarding all older adults as needing and deserving of assistance without regard to the actual needs or desires of the older adult themselves. One example of this is referred to as “caremongering,” the assumption that all older adults are frail and in need of care. This type of language regarding older adults is featured in many of the laws, measures, and procedures developed during the pandemic. While the intent of these interventions is well-meaning, they neglect to acknowledge the diversity of ability and experience of older adults. For example, while it was thought best to “protect” older adults with isolation, retired doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals were being asked to return to the field to help out overburdened hospitals. There was no acknowledgement that these professionals were also older adults.

Figure 8.10. The restrictions brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic hit older adults in congregate living facilities particularly hard. This woman is pictured on her first outing after being on lockdown.

8.5.4 Loneliness as a Mental Health Issue

By Yvonne M. Smith LCSW, hospice social worker and therapist

Loneliness is the discrepancy between the social contact a person has

and the contacts a person wants (Brehm et al., 2002). It can result from social or emotional isolation. Women tend to experience loneliness due to social isolation; men from emotional isolation. Loneliness can be accompanied by a lack of self-worth, impatience, desperation, and depression.

Being alone does not always result in loneliness. For some, it means solitude. Solitude involves gaining self-awareness, taking care of the self, being comfortable alone, and pursuing one’s interests (Brehm et al., 2002). In contrast, loneliness is perceived social isolation.

For those in late adulthood, loneliness can be especially detrimental. Novotney (2019) reviewed the research on loneliness and social isolation and found that loneliness was linked to a 40% increase in a risk for dementia and a 30% increase in the risk of stroke or coronary heart disease. This was hypothesized to be due to a rise in stress hormones, depression, and anxiety, as well as the individual lacking encouragement from others to engage in healthy behaviors. In contrast, older adults who take part in social clubs and church groups have a lower risk of death. Opportunities to reside in mixed age housing and continuing to feel like a productive member of society have also been found to decrease feelings of social isolation, and thus loneliness.

Figure 8.11. This bench (in Manchester, UK) is part of an international grassroots effort to address loneliness by providing residents a chance to interact

8.5.5 Cumulative Advantage/Disadvantage

Cumulative advantage/disadvantage is an approach that seeks to describe how the effects of different opportunities and/or barriers accumulate over the life span. You may hear people describe this as “The rich get richer, the poor get poorer.” A more technical definition might be:

Cumulative advantage/disadvantage can be defined as the systemic tendency for interindividual divergence in a given characteristic (e.g., money, health, or status) with the passage of time. Two terms in this definition warrant special attention. ‘‘Systemic tendency’’ indicates that divergence is not a simple extrapolation from the members’ respective positions at the point of origin; it results from the interaction of a complex of forces. ‘‘Interindividual divergence’’ implies that cumulative advantage/disadvantage is not a property of individuals but of populations or other collectivities (such as cohorts), for which an identifiable set of members can be ranked. (Dannefer, 2003)

What this means is that older adults are not just impacted by their current environment and resources, but also by their environment and resources (or lack of resources) over their lifespan.

For example, let’s compare the dental health of 2 older adults. Mr.Rodriguez grew up in a middle class family who had excellent dental insurance. He had regular check-ups as a child, and later also had dental insurance through his employer. Now retired, Mr. Rodriguez has standard Medicare insurance, which currently does not include dental care. However, Mr. Rodriguez’s retirement benefits do cover dental health, so he continues to get regular check-ups and has no problems with his mouth.

Mr. Stransky grew up in a working class family that did not have dental insurance. He never saw the dentist as a child, and began to have dental problems in his 20s. He worked in retail, and could only afford the minimum insurance plan for his family. He only visited the dentist when in pain, and had to choose the least expensive solution, which often meant pulling the troublesome tooth. Now retired, Mr. Stransky is on Medicare, which again does not cover dental work. He is beginning to lose weight due to difficulty chewing his food. The teeth he has left have significant decay, but Mr. Stransky cannot afford dentures so is trying to make due with what he has.

As you can see by this example, the health status of these individuals is not only affected by the aging process, but also by a lifetime of advantages or disadvantages. This helps explain the diversity of socioeconomic statuses of older adults.

8.5.6 References

Bengtson P. L. & Richard Settersten R., Editors (2016). Handbook of Theories of Aging: Vol. Third edition. Springer Publishing Company.

Choi, E. Y., Kim, Y. S., Lee, H. Y., Shin, H. R., Park, S., & Cho, S. E. (2019). The moderating effect of subjective age on the association between depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning in Korean older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 23(1), 38–45. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1390733

Dannefer, D. (2003). Cumulative Advantage/Disadvantage and the Life Course: Cross-Fertilizing Age and Social Science Theory. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 58(6), S327–S337. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327

Ellis SR and Morris TG (2005). Stereotypes of ageing: messages promoted by age-specific paper birthday cards available in Canada.

Koma, W. et. al (2020). One in Four Older Adults Report Anxiety or Depression Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/one-in-four-older-adults-report-anxiety-or-depression-amid-the-covid-19-pandemic/

International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2005, Vol. 61 Issue 1, p57-73. 17p.

Flett, G. L., & Heisel, M. J. (2021). Aging and Feeling Valued Versus Expendable During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond: a Review and Commentary of Why Mattering Is Fundamental to the Health and Well-Being of Older Adults. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 19(6), 2443–2469. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00339-4

Pearman, A., Hughes, M. L., Smith, E. L., & Neupert, S. D. (2021). Age Differences in Risk and Resilience Factors in COVID-19-Related Stress. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 76(2), e38–e44. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa120

Sargent-Cox, K., & Anstey, K. J. (2015). The relationship between age-stereotypes and health locus of control across adult age-groups. Psychology & Health, 30(6), 652–670. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.974603

Vahia, I. V., Jeste, D. V., Reynolds III, C. F., & Reynolds, C. F., 3rd. (2020). Older Adults and the Mental Health Effects of COVID-19. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association, 324(22), 2253–2254. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1001/jama.2020.21753

van Wijngaarden, E., Leget, C., Goossensen, A., Pool, R., & The, A.-M. (2019). A Captive, a Wreck, a Piece of Dirt: Aging Anxieties Embodied in Older People With a Death Wish. Omega: Journal of Death & Dying, 80(2), 245–265. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/0030222817732465

Varma, P., Junge, M., Meaklim, H., & Jackson, M. L. (2021). Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 109, N.PAG. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110236

Vervaeke, D. and Meisner, B. (2020) Caremongering and Assumptions of Need: The Spread of Compassionate Ageism During COVID-19. Gerontologist, 2021, Vol. 61, No. 2, 159–165 doi:10.1093/geront/gnaa131

Waugh, C. E., Leslie-Miller, C. J., & Cole, V. T. (2022). Coping with COVID-19: the efficacy of disengagement for coping with the chronic stress of a pandemic. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 1–15. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/10615806.2022.2081841

Webb, L. M., & Chen, C. Y. (2022). The COVID‐19 pandemic’s impact on older adults’ mental health: Contributing factors, coping strategies, and opportunities for improvement. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(1), 1–7. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/gps.5647

Yan, Y., Du, X., Lai, L., Ren, Z., & Li, H. (2022). Prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among Chinese older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry & Neurology, 35(2), 182–195. https://doi-org.ccclibrary.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/08919887221078556

8.5.7 Licenses and Attributions for Challenges Facing Older Adults and Their Families

Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World | OER Commons

Lally, N. and Valentine-French, S. ( 2019 ) Lifespan Development: A psychological Perspective-Second edition.Chapter 9-Late Adulthood. Licensed under CC BY NC SA.

Figure 8.7 Images from Funny Birthday Cards and “Dying Reward – Birthday Card” © Greetings Island. Images used under fair use.

Figure 8.8. Demographic Trends of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the U.S. reported to CDC is in the public domain.

Figure 8.9. Demographic Trends of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the U.S. reported to CDC is in the public domain.

Figure 8.10. COVID-19: residents of a retirement home on their first official group outing since Mid March lock-down by Gilbert Mercier is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.11 Photo by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0.